The Hackenberg Riddle

Christian Hackenberg started with his blooper reel. There was a 10-day period in early January when the quarterback didn’t throw a football. While he let the mild shoulder sprain he suffered in his final collegiate game heal, he watched every errant throw and bad decision of his three-year Penn State career.

He sat in front of a video screen in Dana Point, Calif., home of his quarterback tutor, Jordan Palmer, Carson’s younger brother. There were more of these plays than Hackenberg would have liked. More than NFL teams would have liked, too. The idea was to dissect each one, and ask: What went wrong? And how was he going to fix it?

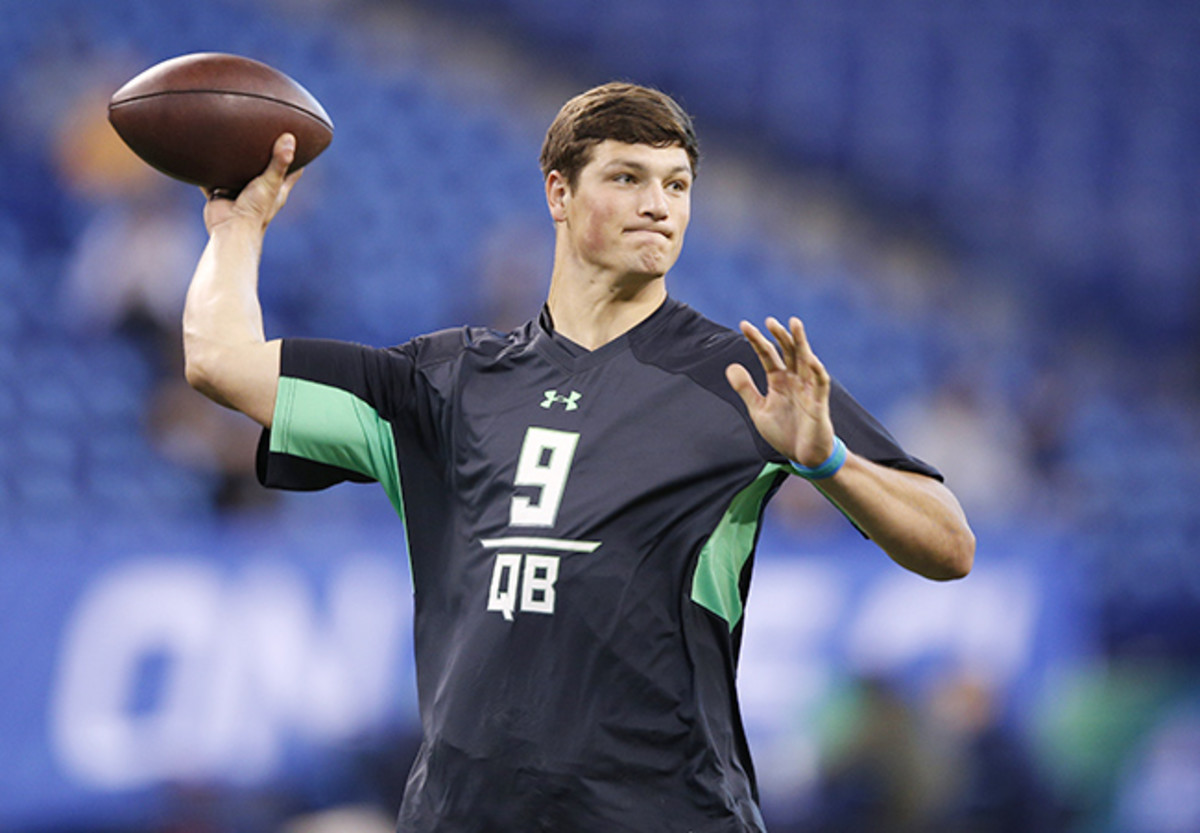

Turns out, those were the exact same questions NFL talent evaluators would ask a few weeks later at the scouting combine in Indianapolis. One NFL head coach said he spent the majority of his team’s 15-minute formal interview with Hackenberg going through film of his unflattering plays.

Hackenberg will make the kinds of throws that separate professional passers from amateurs, the 20-plus yard deep outs and post-corner routes launched from the opposite hash mark. Then there are the bubble screens thrown at a receiver’s feet, or deep passes launched over the target’s head and out of bounds. These are the moments that confound NFL evaluators. Is Hackenberg the overachieving true freshman who surprised even Bill O’Brien by being able to run the coach’s Patriots-derived offense by opening day; or the erratic pocket passer who threw more interceptions (15) than touchdowns (12) as a sophomore, and completed just 53.5 percent of his passes as a junior?

“A mystery,” is how one NFL senior personnel executive whose team scheduled a private workout with Hackenberg puts it. Depending on if you like him or not, the executive adds, you can see what you want to see on his film.

Hackenberg, unsurprisingly, sees it more simply. “I think I ran a pro system my freshman year, and operated in it really well, and I don’t see how you get worse from that,” he says.

NFL teams don’t see how either. That, in a nutshell, is the very riddle they’re trying to crack.

* * *

There’s no tougher job in football than projecting a quarterback’s ability to play at the next level. Being in the crosshairs of this high-stakes evaluation is nothing new for Hackenberg. At Virginia’s Fork Union Military Academy, he beat out a senior for the starting job as a sophomore and led the team to a state title that year. Hackenberg quickly became one of the prized college recruits in the class of 2013.

Alabama coach Nick Saban visited the Christian military boarding school in the hills of central Virginia to watch Hackenberg practice. The quarterback chose Penn State and O’Brien, but the Crimson Tide kept calling. They reached out in 2012, when the severe NCAA sanctions in the wake of the Jerry Sandusky child sex abuse scandal were announced that summer, mandating a four-year postseason ban for Penn State (this was lifted early in the 2014 season) and a reduction in scholarships from 85 to 65. They reached out to people close to Hackenberg again in 2014, after his freshman season, when O’Brien left to coach the Houston Texans.

Neither time did Hackenberg’s vow to Penn State waver, for better or for worse. And there was a lot of both. At age 18, he was the post-scandal, post-Paterno face of the program in a town where the process of moving forward is still awkward. Under those circumstances, the promise of his freshman year was amplified. Here was a confident, big-armed kid playing with 75 percent of a roster who took Michigan to overtime with a 36-yard rainbow pass that only Allen Robinson could high-point, and who went into Camp Randall Stadium to beat the BCS-hopeful Wisconsin Badgers with a near perfect passing line: 21-for-30, 339 yards, four touchdowns, no interceptions.

“He was ahead of his years at 18 years old, more than any other kid I’ve been around, really,” says Charlie Fisher, Hackenberg’s position coach as a freshman. “That Wisconsin game put an exclamation mark on his growth.”

That was also his final game under O’Brien. There’s never a guarantee that a quarterback will continue to develop, but what O’Brien’s staff had seen from Hackenberg was a player who got better every week making decisions in a complicated offense. He had to make both half- and full-field reads, and could change plays before the snap, switching between run and pass or choosing the side of the field to which the play would be run based on the alignment and strength of the defense. There were some mistakes he got away with, and some flaws O’Brien wanted to coach out of Hackenberg after that first season—for example, like a lot of big-armed QBs, he needed to improve accuracy on his touch throws. But he didn’t have the chance.

By Hackenberg’s sophomore year, the coach he had come to State College to play for was gone, and his supporting cast had totally changed. Robinson was playing for the Jacksonville Jaguars. Guard John Urschel and tackle Garry Gilliam were also off to the NFL, two of four starters lost on the offensive line. Because of NCAA sanctions it was a patchwork unit: Donovan Smith was the only scholarship offensive tackle who was not a freshman, and the guard spots were plugged by two converted defensive linemen. For Hackenberg, a sophomore funk set in.

“For a while, Christian shut down, I think, with everybody,” says Micky Sullivan, his high school coach. “I would call him once a week and leave a message, sometimes twice a week, and I wouldn’t hear from him. He was struggling because he took so much responsibility, and the results weren’t good. He just kind of turned into himself.”

Hackenberg’s 454-yard passing outing in the 2014 season opener against Central Florida proved to be an anomaly. There’s no question that the offense brought by new head coach James Franklin from Vanderbilt was a big departure from O’Brien’s system. It leaned on spread concepts and the quick passing game, and seemed built for a mobile, zone-read quarterback rather than a pocket passer like Hackenberg.

Complicating the execution of any scheme was the porous offensive line. There were times when Hackenberg would take a three-step drop and immediately be pummeled by the likes of Joey Bosa. When he did have time to throw, he often seemed hell-bent on making something happen, forcing the ball into places where he shouldn’t have or holding on to the ball too long as he strained for a big play.

“I wanted everything, and I wanted to fix things so bad, and I wanted to be better so bad that at times I took risks that I really wouldn’t take,” Hackenberg admits. “It was just a desire to get something going; to get some type of momentum moving forward. That led to a lot of issues my sophomore year, and a lot of frustration that, ultimately, I brought upon myself.”

The blooper reel got a lot of material that year. But some NFL talent evaluators also see on his film a player who was trying hard to make it work. Penn State finished the 2014 season in the Pinstripe Bowl against Boston College, which had the 11th-ranked defense in the nation and ran a complicated system that threatened an inexperienced offensive line. Hackenberg and new quarterbacks coach Ricky Rahne spent the month leading up to the bowl game devising a system based on film study linking specific blitzes to certain BC defensive personnel groups. Come game time, Hackenberg was able to recognize where pressure was coming from before the snap and send the protection that direction. He threw for 371 yards and four touchdowns in the win, and was only sacked twice.

Penn State’s offensive identity was a moving target for most of Hackenberg’s sophomore and junior seasons (Franklin fired his offensive coordinator, John Donovan, in November of last season). Hackenberg broke 12 school freshman passing records his first season in Happy Valley, but five games into the 2015 season Franklin publicly deemed the offense’s identity one of running the football and managing the game. If they were going to run, Hackenberg focused on making the right run reads. During a rainy win against Rutgers last September, Rahne recalls Hackenberg checking out of one run play, and when Rutgers changed its defensive look, he checked back into the original play. The result was a 75-yard touchdown run by tailback Akeel Lynch.

While he let the hits and the offense’s struggles get to him more than he liked as a sophomore, people around him noticed his resolve not to let that happen again his junior season. Hackenberg actually had his lowest frequency of interceptions in 2015: One per every 59 pass attempts, compared to every 32 attempts as a sophomore and every 39 attempts as a freshman.

Is he coachable? That’s a question a lot of NFL teams ask about players, and the most common one Rahne has heard. His answer is a simple one: He learned two offenses in three years, with different terminology and pass concepts and footwork.

“The only times we ever had any issues is when he was more frustrated with himself than anything,” says Rahne, Hackenberg’s quarterbacks coach for two seasons on Franklin’s staff. “The same thing you see from No. 12 in New England, that when he is not playing well, he gets upset. If that’s the worst thing you’ve got is that he’s hard on himself and wants so desperately to be successful, you can coach that.”

* * *

Two years ago, when the runaway hype over his freshman season had analysts talking about him as a future top-five pick, it seemed inevitable that Hackenberg would leave for the NFL a year early. But his next two seasons raised more questions than answers. Things didn’t go the way Hackenberg had wanted, right down to his Penn State finale.

He left the Jan. 2 TaxSlayer Bowl, a 24-17 loss to Georgia, with the shoulder injury. The last minutes of his college career were spent on the sideline, wearing sweats and a headset. When he met with the media after the game, he didn’t begin by declaring his NFL intentions, nor did he have any remarks prepared. His announcement was something of an impromptu one. Midway through his interview, he started thanking people: O’Brien for bringing him to Penn State, Rahne and Donovan, the strength staff, trainer and even the video director. In the much-scrutinized relationship between Hackenberg and Franklin, the seeming Freudian slip was easy fodder for internet headlines: “Christian Hackenberg thanks everyone but his coach.”

“I’m sure ‘Hack,’ in hindsight, wishes it would have gone a different way,” Rahne says. “But it didn’t. In the heat of the moment, things happen, and you wish you could take ’em back, but you can’t. But I know those sort of things were handled behind closed doors, and I know they are a lot better now. It was an emotional time for him, and he made a mistake, but he owned up to it, and you move on.”

Two NFL teams who met with Hackenberg at the combine said they specifically asked Hackenberg about his omission. His answer was the same one he gives publicly: He found Franklin afterward, and thanked him one on one.

No one, not even Hackenberg, tries to hide the fact that his relationship with Franklin was different from the one with O’Brien. As a five-star high school recruit, he chose O’Brien. And O’Brien was the offensive coordinator and a fixture in the quarterbacks room, whereas Hackenberg spent less time with Franklin, who devoted his attention to recruiting and rebuilding a viable roster after the sanctions.

Two weeks ago The MMQB’s Robert Klemko reported that two personnel sources told him Hackenberg had shifted blame to Franklin when their teams asked about his declining production his sophomore and junior seasons. But four high-ranking club officials who were part of their team’s interview process with prospects, speaking for this piece, said that was not how Hackenberg responded in their meetings.

“His answer was that he didn’t play as well, and there were things he needed to get better at,” one head coach said. One senior executive said he was impressed that Hackenberg didn’t throw Franklin under the bus, despite questions that set him up to do so. Another team decision-maker said he could read between the lines that Hackenberg and Franklin weren’t especially close but that Hackenberg did not blame his coach. During Hackenberg’s 12 formal interviews at the combine, some teams pushed that button harder than others, and some may have interpreted his answers differently. Hackenberg doesn’t believe he left any room for interpretation.

“It was a very easy answer for me. There are some things that I have to get better at, and that’s the way I approached it going into the interviews,” Hackenberg says. “It’s the greatest team game on the planet, but you have to be able to uphold your end of the bargain. I did that at times, and at times I didn’t. That’s the messaging I wanted to get across, is here’s where I could have gotten better. I own everything I put on tape. I did it. It wasn’t anyone pulling the trigger but No. 14.”

The point of Hackenberg’s pre-draft tutoring with Palmer, starting with that blooper reel, was for him to fix the mistakes that give NFL teams pause. His biggest flaw at Penn State was consistency; being able to make those great NFL throws, but not being able to do it play in and play out. His cannon arm is one of his most appealing attributes, but his deep pass accuracy lagged behind—in 2014 he completed just 33.3 percent of passes that were 20-plus yards, 89th in the nation; in 2015 his deep completion rate was 39.7 percent, 71st in the nation, according to Pro Football Focus.

Hackenberg spent two-and-a-half months out in Orange County, working from 5:45 a.m. to noon to correct the root cause of his accuracy issues: failing to start each pass from a good throwing position. At times that was because he was under pressure, with defenders in his face or at his feet. He was sacked 103 times in his college career. Other times sloppiness was to blame. He was taught different footwork in each of his three seasons at Penn State, muddying his mechanics and his muscle memory.

“Did the pressure have an effect on his fundamentals, at times, the last two years? Yeah, I think it did,” Rahne says. “And that was something I should have done a better job at correcting. That’s my job as a coach, to make sure he doesn’t fall into those bad habits, and that’s something that I own. But do I think it’s going to affect him over the next 11, 12 years of his NFL career? I don’t, no.”

To rebuild Hackenberg’s throwing foundation, Palmer began each session with 10 minutes of this drill: He’d toss a football on the ground, so that it would bounce in an unpredictable direction, and Hackenberg would have to grab the ball and snap into the same starting position, with knees bent and two hands on the ball. Another drill Palmer taught Hackenberg helped him activate his hip while he was throwing, so he could put the power of his core and lower body behind each pass, and then simply use his arm to follow through. Hackenberg texted Rahne about this drill, raving about how much it helped his accuracy.

For Hackenberg’s March 17 pro day, Palmer designed a workout that made Hackenberg look less like a project and more like an NFL-ready quarterback. The script included throws from pretty much every drop used in NFL offenses, including quick game, three-step, five-step and out of pocket from the shotgun, and three-step, five-step, seven-step and play-action under center. Palmer took ubiquitous pass concepts from NFL playbooks, like sluggo/seam, and had Hackenberg throw a five-yard hitch not in isolation but as part of the progression of that pass concept. A red-zone session highlighted accuracy on throws that were back-shoulder or over a defender’s head, and they ended by showcasing his arm with a few deep throws that traveled 60-plus yards in the air.

“The reason Christian’s pro day went so well, and it looks different than it did last year, is because for two-and-a-half months Christian got to focus on himself,” Palmer says. “It’s my job to make sure teams look at that and go, ‘Wow, if he was with Jordan for two months, I can’t imagine if I got him for four years.’ ”

* * *

Micky Sullivan, Hackenberg’s coach at Fork Union, has a favorite story that illustrates his player’s confidence in himself. After Hackenberg’s senior season, he was invited to play in the Under Armour All-America Game in Florida. Herm Edwards was the coach of Hackenberg’s team, and the day before the game he asked the captains to walk out to the middle of the field. Hackenberg walked out. The only problem was, he wasn’t a captain.

“His expectations were, ‘I’m that guy,’ ” Sullivan says. “Nobody has to vote, nobody has to decide—I’m that guy.”

When he gets to the NFL, though, for the first time since the beginning of his sophomore year of high school Hackenberg will likely not be that guy. Most people around the NFL see him as a developmental player, best suited for a team with an entrenched veteran starter whom he can learn behind. Maybe somewhere like Kansas City—GM John Dorsey is a Fork Union grad—or Dallas. There’s also the wild card: O’Brien’s Texans, one of the dozen teams who scheduled a formal combine interview with him. Houston signed Brock Osweiler to a $72 million contract, with $37 million guaranteed, so they almost certainly will not take a quarterback in the first two rounds. But if Hackenberg is there in the third, or the fourth?

And that’s the question: How long will Hackenberg last? Three executives told The MMQB they graded Hackenberg as a third-rounder, but your draft stock is not the average. It’s where the team that regards you highest grades you.

There’s a divide between those who see a player held back by a lack of talent around him and an ill-fitting offensive system, and those who believe great players figure out how to be great regardless of circumstance. Teams are still trying to collect more information to crack the Hackenberg riddle: He visited with the Cowboys last week, and the Eagles and three other clubs so far have scheduled private workouts and visits with him.

Said the NFL head coach: “Everybody thinks he struggled the last two years, and he has. I can see him being evaluated down a little bit, because he hasn’t progressed. But is the talent there? Yes it is. He needs to focus on his fundamentals and getting his confidence back, because he’s not playing with the confidence he did as a younger player.”

Said the senior personnel executive: “If you draft him in the second round or higher, it’s because he’s 6-4, has a good arm, has upside, and you know he can learn. But of course there’s a concern, because you always want to see it on tape first.”

At the combine, Hackenberg said his “biggest fear” is not being able to reach his full potential. For any NFL team considering drafting him in the first two rounds, the feeling is mutual.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.