Inside the Film Room With… Carson Wentz

I cringe at the question that I’m about to ask Carson Wentz. It’s one he’s heard a thousand times, which is why I’ve put it off until the end of our sit-down, even though it makes much more sense to ask up front. It’s the question that everyone has asked upon first hearing about him. I preface it with a meek apology and then proceed to flub it: How does a guy born and raised in North Dakota who is lightly recruited and goes to a Division II school…

“FCS,” Wentz politely corrects.

Right. Take Two: A guy born and raised in North Dakota, lightly recruited, goes to an FCS school, starts just 23 games—how does he become a top-two rated NFL draft prospect?

And here, Wentz recites his speech. “I think first of all, if you can play, you can play. Football is football; I don’t care if you’re doing it in Division II, NAIA or in the SEC or anything in between. Everyone’s got to make an adjustment. I think it’s what you bring to the table, what you’ve done, what you’ve put on film. And then your physical traits and all the intangibles that come with the position. I think level of competition gets put on the backburner when you see what else is brought to the table. And if anyone wants to use that as a doubt in their minds, and I’m sure there are plenty of people who do, then I just use that as motivation, play with a little chip on my shoulder and I’m ready to prove everybody wrong.”

Clichéd questions get clichéd responses. But here’s the thing about clichés: They’re true. That’s how they become clichés. Everything Wentz said is true. He can play. His film is quite impressive. You’re almost lulled to sleep watching it because he handles all the duties and nuances of quarterbacking so easily and thoroughly. And then every few plays, he drops a perfect touch pass in the bucket or rockets a far-hash throw to the first down sticks. Or, he runs—much more like Cam Newton than, say, Joe Flacco. Suddenly, you’re jolted back awake.

Three of the very best draft analysts in the country—Jon Gruden, Mike Mayock of NFL Network and Greg Cosell of NFL Films—have said this unknown kid from North Dakota State (FYI, it’s in Fargo), is the most pro-ready quarterback to enter the NFL since Andrew Luck. But what does that actually mean, pro-ready? This is what I went to Fargo to learn. For the entire hour leading up to my clichéd question, Wentz taught me.

* * *

We’re watching Wentz’s game against Northern Iowa. Spoiler alert: he orchestrated a 10-play, 79-yard, two-minute come-from-behind touchdown drive to win by three. At one point, the North Dakota State Bison were backed up on their own 10-yard-line, facing third-and-20, with no timeouts and 2:03 on the clock.

Among Wentz’s games, this is surely the one NFL teams (including the Eagles) have studied the closest. Because one reason the Bison were behind is Wentz made some mistakes—three resulting in turnovers. You learn as much from a quarterback’s lows as you do from his highs.

Before any of this, however, there were plenty of plays that seemed routine but really build the case for Wentz’s “pro readiness.” And not all were positive. One was a sack on the game’s second series. I chose it because it was a snapshot of NDSU’s “pro style offense.” After pounding the ball from heavy run formations on two of the previous three snaps, then going pistol read-option on the fourth, the Bison spread into a shotgun 2x2 set (two eligible receivers on one side, two on the other). Wentz explains the whole play in one quick, fluid breath, and I’m left trying to catch mine.

“So this is Gun Pass 41 Power Base Set Chevy X Glance here.” (By the way, the film hasn’t rolled at this point, Wentz has only seen the formation.) “It’s our pass power base set action—we rarely did it out of shotgun. The protection kind of broke down. Right guard is pulling for the widest defender in this picture. And then everyone else is just down-blocking. The running back is faking inside ‘power’ [run] to the right and then he’s really just looking for anything extra to block. For our receivers, we had a smash concept to the field [i.e. two receivers high-lowing one defender] where I was going to work, but Northern Iowa’s defensive line ran this twist game.”

Got it? Here’s how it looked.

* * *

To open the next series, Bison tight end Luke Albers shifted before the snap to create a 3x0 I-formation out of heavy “22” personnel (two backs, two tight ends), with the three eligible receivers all to the short side of the field. I’ve never seen this formation in the NFL, let alone college, where the wider hashmarks leave considerably less space to the field’s short side.

“Yeah, we don’t have a lot of options here,” Wentz says. “We were just big on a lot of unbalanced sets and different ways of getting the defense to either show their hand or just be outnumbered.”

The play’s geometry pretty much ensured that the running back would get the ball. And he did, on an outside zone run to that short side, for a gain of eight. “This was a big concept for us. We call it 47-slant. The guys did a good job blocking it.”

It’s a nondescript play but a perfect illustration of the balance, maybe even run-heaviness, of North Dakota State’s offense. “I think I threw 40 times this game, and I don’t think I broke 30 in any other game in my career,” Wentz says.

This may seem antipodal to a quarterback’s pro-readiness. Logic suggests the more a QB throws in college, the more ready he’ll be for the pros. But NFL coaches see it differently. In fact, this brings us to Exhibit A in our case for Wentz’s pro-readiness: his tremendous grasp on how the running game works. He has the ability to check to certain runs at the line of scrimmage, a la Peyton Manning. There’s more involved that what meets the laymen’s eye here. As Wentz says, you think about “what kind of front the defense is in; where the linebackers are; whether it’s two-high safety or one-high. A lot of different things go into calling the run game—especially at the line of scrimmage.”

This isn’t to say Wentz is not still primarily evaluated on his passing prowess. The rest of the plays we’ll see will be through the air, starting with a red zone throw along the field numbers. This play offers our next piece of evidence of Wentz’s pro-readiness. Exhibit B: He’s a full-field, multi-progression reader. Not to be confused with a pure progression reader, which would imply that the order of his reads are built into the play’s design and are therefore the same every time. No, Wentz’s progressions are often contingent on the defensive look. And so the same play’s reads can vary from snap to snap.

The play we watch was out of North Dakota State’s first empty backfield set of the game (“empty” has become a facet of “pro style” offense).

“We’re in Gun Nasty High,” Wentz says. “It was really just a unique empty formation we put in for facing these guys. We called 50 Combo Stretch and then Dodge up top. So we got stretch down here, a smash concept [again, high-lowing a defender]. And then those two in that bunch set to the right are really like double-post routes. So for my reads, I’m clicking to the smash on the left, to that corner, then across to my right to the inside post and then to the other post. And then option No. 4, the in-route down below, is kind of my checkdown.”

So the read is 1-2-3-4, I say, moving the laser pointer from left to right across the screen.

“Yup. And it was really taking a shot. It was 1, 2 or 3. So I clicked all the way back to option 3. The cornerback, who I didn’t pick up in my vision as I was scanning across, made a heck of a play. When I threw this ball I thought we had six points. I fit it right inside that Will linebacker but he fell off and did a good job.”

Wentz made the right decision, the corner just made an athletic, highly alert stop. Classic case of good offense vs. good defense, and this time the defense won. NFL talent evaluators don’t care that it was incomplete. They care that it was a well-thrown ball on a complex, specifically game-planned progression read.

* * *

The very next snap is similar in that it was a smart decision and a well-thrown ball that again fell incomplete. (A drop.) It offers Exhibit C: Wentz’s aptitude for pre-snap adjustments at the line of scrimmage. It was not a full audible, just a tweak he called for his receivers on the right side.

“Yeah, so we jump into Liz-out and then we’re going 60 Combo X-drive Chevy. I changed it; Chevy is our smash [once again: high-lowing a defender]. I saw the defense rolling into Cover 3 pre-snap so I just changed it to our Indy concept, which is our takeoff on the outside and a 12- to 14-yard speed-out from [the inside receiver]. I caught the corner kind of peeking a bit. This season we threw this Indy, this 12- to 14-yard speed-out to the slot receiver here a fair amount. So here, I saw the safety playing pretty aggressively on that speed-out. So I just triggered it and let it rip.”

For the sake of being thorough, I have Wentz diagram the play. Sure enough, there’s more. He gets into the protection—that was the “60 Combo” part of the call—plus the running back’s pass-blocking reads and contingent route running responsibilities.

Which brings us to Exhibit D in Wentz’s pro-readiness: his adroitness in setting pass protections. Instead of having the protections built into the play call, North Dakota State would have Wentz get to the line of scrimmage, eye the defense, and then call the protection. This is Tom Brady type stuff. It’s a step or two beyond identifying and adjusting to blitzes. Seeing a blitz and changing the protection is 200-level quarterbacking, maybe 300-level depending on how well the defense is disguised. Getting to the line and calling the entire protection from scratch is 400-level quarterbacking.

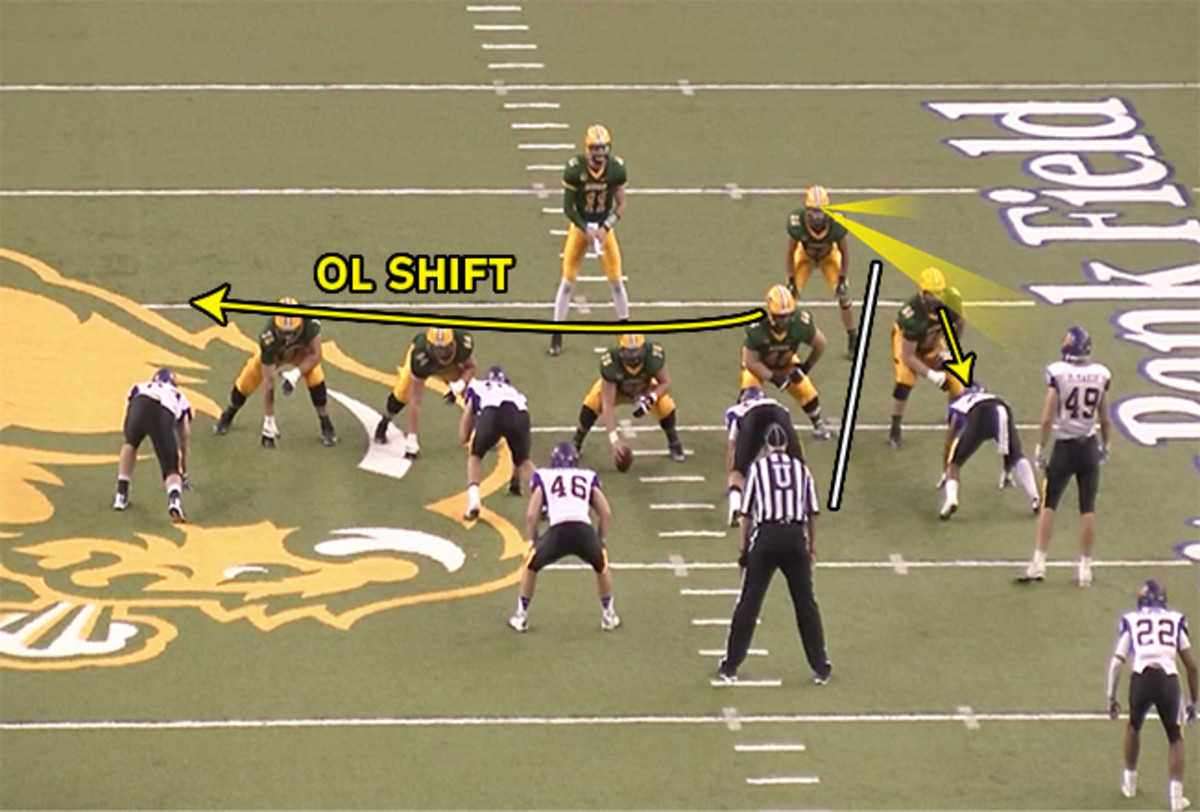

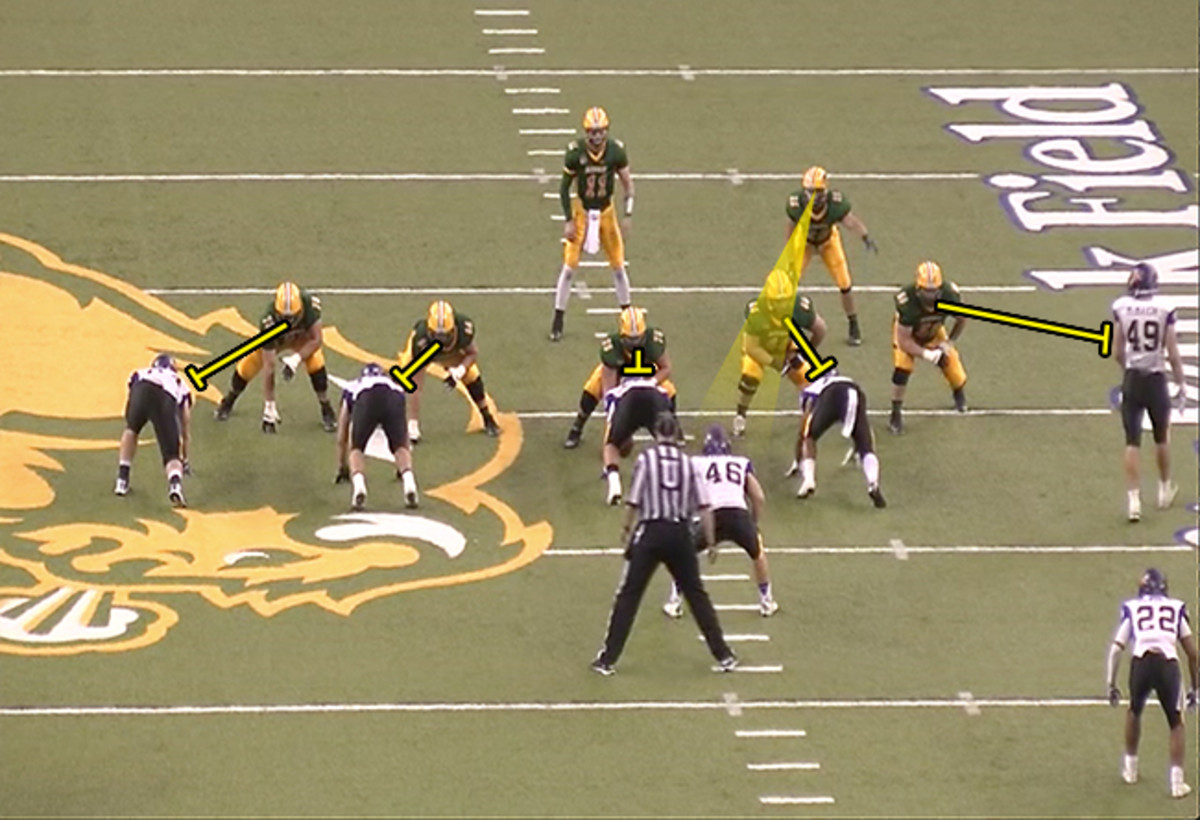

To get a better sense for Wentz here I had him diagram one of his protection calls from later in the game. It was an excellent example, too, because Northern Iowa’s defensive line shifted after the call, which prompted Wentz to change it.

“I’ll draw what we had called and then what we switched to when they shifted,” Wentz offers. “We had 62 called right away, so right here [at left tackle] we’re going to be man-on-man. And the rest of these guys are going to slide to sort out four of the five defenders in case anything else comes. So we’re really just running an O-line slide to the right. And then the back is going to be 1-to-2-to anything out wide. We say No. 3 to the man side. And he’ll also scan to No. 4 to the slide side, as we call it.”

As you might surmise, this is a whole different job than just getting to the line of scrimmage and shouting hut-hut-hike. If you’re inclined to try to map out what Wentz said, here’s a still shot.

Oh, and remember, this was before the defensive line shift. After the shift things changed.

“So now they shift this three-down front. So we fan it in this case. Now we’re just five-for-five; a man-match call. The back’s going to be here [Wentz points to linebacker No. 46] and then look for anything extra. I’m pointing out this direction that they’re going to fan it or match it in this case.

Wentz calls for the film to roll. “The center actually gets beat here and the back just ends up getting in the defender’s way to help out. Ideally, numbers-wise, the back should be getting out in a route. But he just found a spot to add himself because the center got beat.”

VIDEO E TK

* * *

So, to summarize the case for Wentz being the most pro-ready QB since Luck:

Exhibit A: grasp on the running game

Exhibit B: full-field, multi-progression reads

Exhibit C: pre-snap adjustments in the passing game

Exhibit D: setting protections

Our next few exhibits will pertain to quarterbacking traits that we hear about more regularly. Like character and accountability. Call this Exhibit E. For it, you can submit Wentz’s response to each of his three turnovers.

The first was an interception by safety Tim Kilfoy. Wentz recognizes the play just from seeing the third-and-12 on the scoreboard. “Yeah I threw an interception here.” His description is, like all the others, a mouthful that spills out of fluidly, without hesitation. (“This is Gun Right Wide 60 Combo Seattle Y Deep Hank.”) Wentz explains the route combinations, and then his reads. “I saw the DB roll to a Cover 3 Cloud look and I tried to force it down the seam because against Cover 3 I like working the seams.” Then, Wentz explains the route combinations further, detailing the geometry of each one and the minor tweaks that could have helped things go differently. After this comes the laymen’s summary: “The safety made a good play and I definitely forced it. Should have just checked it down.”

A little later, this same route concept is called again. This time, Northern Iowa is in Cover 6. In college, the field spacing can make Cover 6 look an awful lot like certain Cover 3 concepts. The difference, in short, is that the safety in Cover 6 tilts away from centerfield and is planted more firmly in the seam.

“We got that Seattle Y-Deep Hank play here again,” Wentz says. “The one I threw the pick on earlier. So here I wanted to take my Y receiver [the tight end] because this is really your Cover 6. This is Cover 2 to the [wide side of the] field, Quarters coverage to the short side. So I really could have maybe taken a shot on the edge to this receiver, but I didn’t like my matchup terrifically, especially with this safety [looming].”

The play didn’t pan out well; Wentz and the tight end were on different pages. But consider it another “negative” play that, from the standpoint of translating a quarterback from college to the pros, goes in the plus column. What often separates a top-level quarterback on film are the throws he wisely does not attempt. No advanced stat will ever capture this—you can’t quantify what doesn’t happen. But NFL coaches and scouts see it, and here they saw Wentz deliberately avoid making the same mistake twice.

As for Wentz’s other two turnovers, the first was an interception in the tight red zone. He threw a little behind receiver Zach Vraa on a quick-slant and the ball deflected high into the air. The O-line had several snafus, allowing defenders to contact Wentz on his release. Vraa might also tell you that he should have made the difficult catch.

I ask Wentz how much of this turnover a coach would blame on the quarterback, how much on the receiver and how much on the offensive line.

“Boy I don’t know what the coaches would say,” Wentz replies, clearly having never thought about it before. “I would take full responsibility. I don’t care if I’m getting hit, I got to deliver this ball out in front. There’s nothing on the receiver there. Gotta get it out in front.”

The third turnover was a lost fumble late in the fourth quarter. I know what you’re going to say you should have done differently here, I tell Wentz.

“Yeah, not fumble?”

Sometimes it’s that simple. “We had a hole and I thought I had it pretty secured,” Wentz says. “The guy just reached in and popped it out. I was pretty frustrated.”

* * *

I only included the fumble in our film sequence to help build the narrative for the final drive, which followed immediately. That drive was a microcosm of Wentz’s greatness. We’ve seen a lot of plays with negative outcomes so far, but for the most part, the plays were well-quarterbacked. When projecting a player to the NFL—or really, when evaluating any player—you have to consider how the action unfolded more than the action’s result. You trust that ultimately you’ll get more positive outcomes than negative if a guy plays the right way. This idea culminated on Wentz’s game-winning drive.

Exhibit E of Wentz’s pro-readiness—the character and accountability—was a quarterbacking trait more familiar to casual fans. So is Exhibit F: his combination of arm strength and accuracy.

We jump to the third-and-20 with the Bison on their own 10, down 28-24 with 2:03 left and no timeouts. Wentz, tall in the pocket, threw to the far sideline for a gain of 12.

“Yup so third-and-20 here. We just had a 560 Combo Y-Hank play. So it’s just comeback routes on the outside, and then the tight end is running the middle, sitting at 10 yards. And then a skinny route over the top. The defense rolled to this Cover 3 Cloud, which they did a lot, as we’ve talked about, and I knew where I wanted to go. Really to the [far-hash] comebacker because it was the only throw I had. That’s where they’re softest in this 3-cloud coverage. The kid made a good play coming back to secure this catch. Stayed in bounds, now the clock’s running. We got to go. And so we run up to the line. Fourth-and-8 we called the next play.”

This actually wasn’t even close to Wentz’s best far-hash throw on the day. He had completed a handful of others—all throws that many NFL quarterbacks don’t even attempt.

The fourth-and-8 fell into this category, as well.

“So now we’re running up to the line,” Wentz says. “I’m going to my favorite play, four vertical routes, with comeback options on the outside.”

I tell Wentz I assume he was making all these play-calls here.

“Yeah. I’m yelling ‘Left wide! Left wide!’ getting us lined up, yelling the play-call, yelling the protection and everything. Again they rolled to this 3-cloud coverage and I again knew it was a [wide side of] field comebacker like this. Fourth-and-8, gotta deliver, and we did. The kid did a good job of keeping his one foot in. He made me a little nervous but, fourth-and-8, we’re staying on the field. The drive’s still alive.”

* * *

We see a few more sterling examples of Wentz’s Exhibit F (arm strength and accuracy) moving the Bison downfield. Throughout the drive, he never once spiked the ball to stop the clock.

“Every down is important. I’d much rather call a play than spike it because we’re very efficient at getting to the line and getting a play called, and we’ve done it a number of times…. As long as you got a guy who’s in control out there and can communicate, you can get a lot accomplished.”

A series of quick strikes, checkdowns and an unbelievable touch throw (and catch) down the middle against tight Tampa 2 coverage helped put the Bison at Northern Iowa’s 18-yard-line with less than 50 seconds to go. We’re about to see the game’s final play, and it’s Exhibit G in Wentz’s pro-readiness case: the It Factor.

(Let’s be clear about something: It Factor is a totally empty declaration that fans and lazy announcers use for describing a player who is good for reasons they don’t understand. It Factor says absolutely nothing. But since the phrase isn’t going away, we might as well assign it some sort of meaning. A modest proposal: The It Factor is a player’s ability to congeal all of his best traits and use them in the moment they’re needed most.)

Wentz showed his It Factor on an 18-yard, game-winning, back-corner touchdown against double coverage.

“So we’ve just completed one, we’re running up to the line. I called, I believe our Z Drive play and I had a shake route called initially to these two receivers on the left. So a shake would have been: outside receiver’s running a hitch, inside receiver’s running a corner-post. But I saw this safety roll to the middle of the field and I knew that shake route would be dead against that. So I called out for this smash concept vs. 1-high coverage to be converted to a slot fade. And then right at the snap, I saw the cornerback go from zone alignment and he turned his hips and was now square on man. I knew I was going to that slot fade right away. The kid made a heck of a catch.”

Perhaps most remarkable was that Wentz made a pre-snap adjustment at the line of scrimmage out of hurry-up. You rarely see that. “Usually you don’t have time for that,” he says. “But I knew this could be a big play and I just yelled ‘Easy! Easy!’ and just got the snap real quick. I’m changing to the slot fade vs. man coverage, it’s a big play for us.”

Then Wentz sounds sheepish for the first time. “Oh, yeah, and that happened,” he says as we watch from the end zone angle. He’s referring to the fact that he initially lined up in shotgun behind the right guard. His center gave him a “move over!” gesture.

I tell Wentz I once saw Drew Bledsoe do that. “What I’d like to say is, hey, it’s fair because it was two-minute and everyone’s running up there anyway and I’m communicating across the board.” As his rationalization expands, so does the sheepishness. “But yeah, it was still pretty funny.”

After the comeback win, Wentz broke his wrist and was sidelined until the FCS Championship, which he started and won 37-10 over Jacksonville State. This brings us to one final item. Like Exhibit G—It Factor—this item is nothing but a grand platitude. In fact, it’s probably not even worth submitting in a man’s “pro-readiness” case. But here it goes: he’s a Winner.

Unlike most of our other exhibits, being a “Winner” is not a trait. You can’t go out and practice being a winner. And so it’s ridiculous to include in any discussion for how a player might translate from college to the pros. That said, it’s also impossible to ignore the fact that the win over Jacksonville State gave Wentz a fifth national title in his college career. That’s five years, five rings. He was only the starting quarterback for two of them, but still: This is someone who enters the NFL having known only a winning environment.

No NFL team is winning five Super Bowls in the next five years. Wentz, like everyone, will have to deal with adversity in the pros. We’ll soon find out how ready he really is.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.