Best of Dr. Z: Jack Lambert, Defender of What Is Right

This week at The MMQB is dedicated to the life and career of Paul Zimmerman, who earned the nickname Dr. Z for his groundbreaking analytical approach to the coverage of pro football. For more from Dr. Z Week, click here.

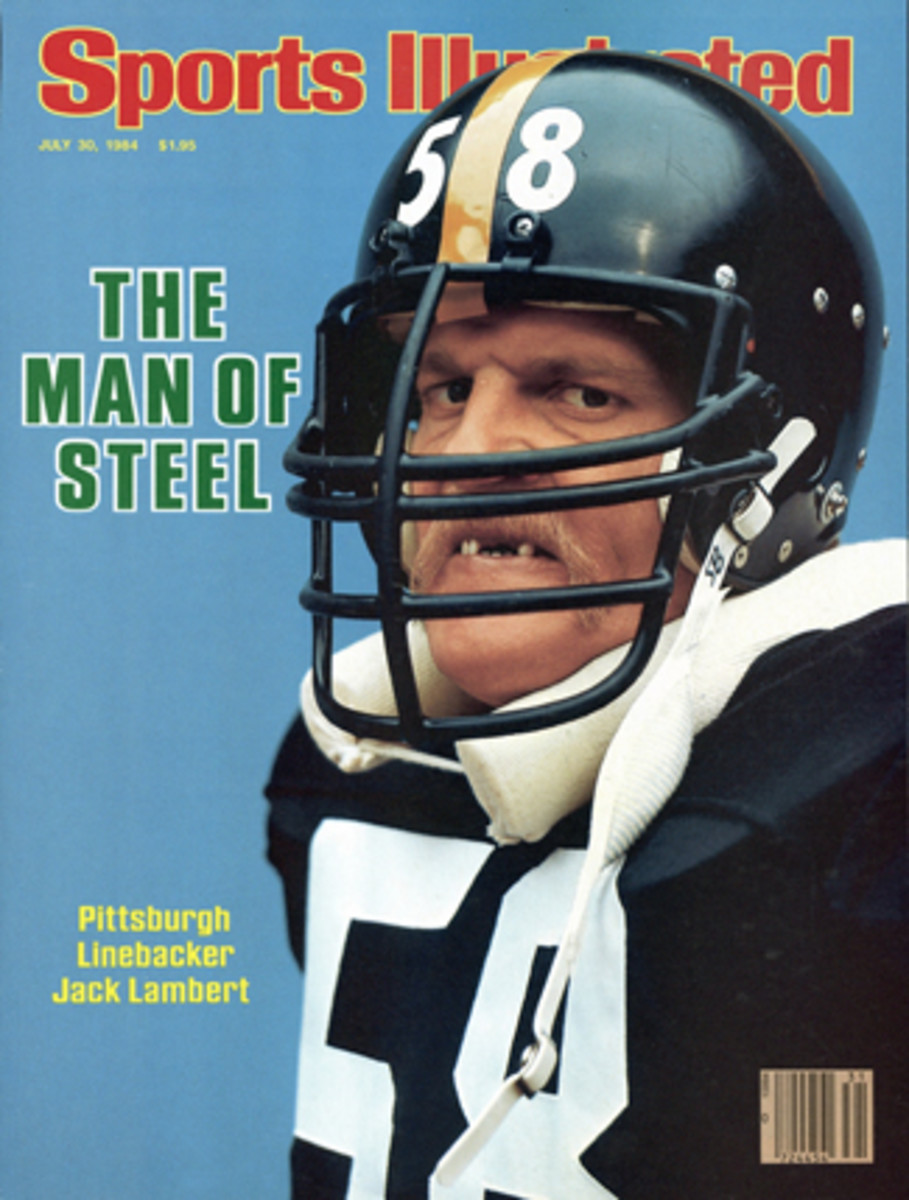

This story originally appeared in the July 30, 1984, issue of Sports Illustrated.

The painting hangs on the wall outside the office of Art Rooney Jr., the coordinator of the Pittsburgh Steelers’ scouting operations. It’s not the kind of thing you’d want your mother or your wife to see. It’s what Attila must have looked like while he was sacking a village, or the way a Viking chieftain was with his blood lust up. Only this Viking wears No. 58 and he’s dressed out in the gold and black of the Steelers, eyes flashing in a maniacal frenzy; blood flecking his nose; his mouth, minus three front teeth, bared in a hideous leer. Jack Lambert’s portrait epitomizes the viciousness and cruelty of our national game.

The portrait was done by Merv Corning. It was one of two he submitted to the Steelers’ publicity director, Joe Gordon, for possible use as a program cover, and it was rejected immediately. Too scary. Rooney saw it. He called Corning. “Can I buy the original?” he said. The deal was made, and Rooney hung it outside his office. Then he had misgivings.

“I thought, ‘Holy hell, Lambert’s gonna pull this thing off the wall when he sees it,’ ” Rooney says. So he removed it and sent for Lambert.

“Jack,” he said. “I want to hang it on the wall. What do you think?”

“He got very quiet,” Rooney says. “He looked at it. He studied it. He stepped back, stepped forward. Then he asked me, ‘Can you get me a couple of copies?’ ”

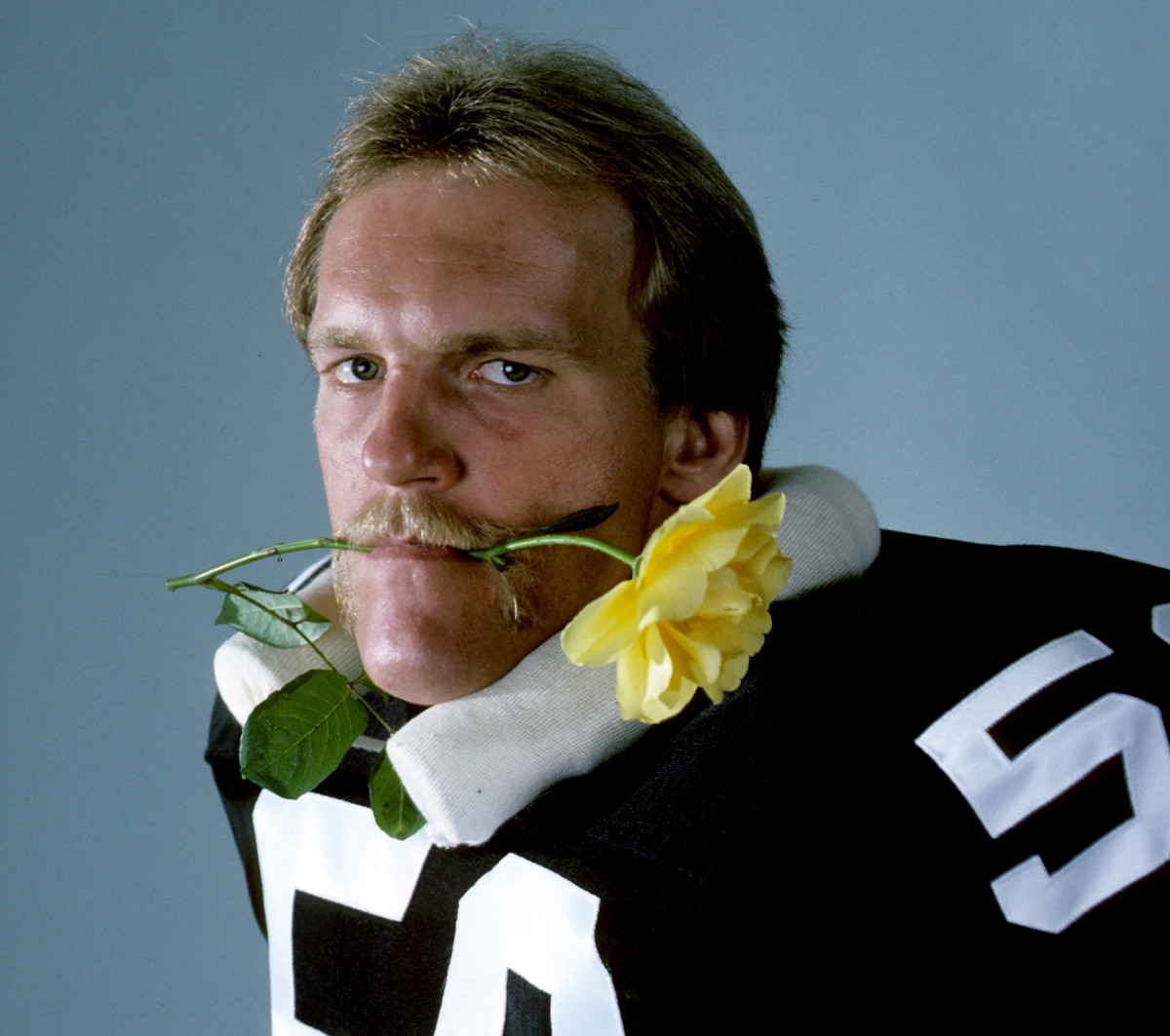

Is that really the image Lambert wants, a toothless monster ravaging the NFL? Off the field he’s a quiet, extremely private man, a bird watcher and avid fisherman. A bachelor, he owns a house in the exclusive Fox Chapel suburb of Pittsburgh, and he spent much of the off-season ensuring greater privacy by building himself a country retreat on 85 acres he bought about 40 miles northeast of the city. At one time he was bothered by all the Count Dracula-Darth Vader stuff everyone used to write about him. When the Steelers played the Rams in the ’80 Super Bowl, Jim Murray, the columnist for the Los Angeles Times, referred to him as “the pro from Pittsburgh, Transylvania.” That same year the Steelers’ highlight film called him “Count Dracula in cleats.” In 1981 Azra Records of L.A. put out a platter in the shape of a football; it was called “Mad Man Jack,” and two bass drums pounding all the way were supposed to simulate Lambert’s feet pumping before a play, a trademark of his early pro days.

“All that stuff about Jack, it’s a bad read,” says Andy Russell, the right linebacker on the ’74 and ’75 Steelers Super Bowl teams. “He’s a great player, and he’ll be remembered for a long time, but for all the wrong reasons.”

But here’s Lambert, carefully scrutinizing that savage picture in the Steelers’ office and deciding, “Yep, that’s me, all right.” How come?

“It’s like the old Greek drama,” says Rooney, a dramatic arts major in college, “where they’d wear masks, and eventually the mask became the face. Well, the mask has become Jack’s face. Right now he thinks he’s John Wayne. Actually, though, he’s sort of a larger-than-life type guy.”

* * *

As Jack Lambert reported to camp last week for his 11th Steelers season, he still seemed larger than life. He came to the Steelers a tough, skinny kid out of Kent State, and he found a spot on a team that was just reaching the crest of its greatness. He arrived at exactly the right time, in exactly the right place. Pittsburgh fans have always appreciated talented athletes, but they reserve a special place in their hearts for their tough guys—Fran Rogel, Ernie Stautner, John Henry Johnson, those people. And Lambert played the ultimate tough-guy position, middle linebacker.

At one time middle linebackers roamed the league like Goliaths. Nitschke, Butkus, Schmidt—names as tough as the people who carried them. Willie Lanier, with that pad he wore on the front of his helmet. Mike Curtis, the Animal. Bob Griese talks about staring across the line at Butkus and feeling his legs turn to jelly. Gene Upshaw, the Raiders’ ex-guard, remembers the terror he felt when he looked into Lanier’s eyes.

But then a few years ago something sad happened to these great middle linebackers. The 3-4 defense robbed them of their identity. They divided, like an amoeba. Instead of one, there were two of them, inside strong and inside weak, or, in the Steelers’ case, left and right. The great gunfighters of the past had gone corporate. It was as if Wyatt Earp had taken on a job with Pinkerton’s, or Bat Masterson had become director of security for the First National Bank. It happened to Harry Carson with the Giants, then to Jack Reynolds when he went from the Rams to the 49ers. And then the last of them, the last of the great old middle linebackers, Jack Lambert, got his two years ago.

“Oh yes, Mr. Lambert, I’ve heard of you. And what position do you play, Mr. Lambert?” And instead of snarling out “middle linebacker” through chipped and broken teeth, Lambert would answer “inside linebacker left.” Sounds like a traffic signal.

“I can close my eyes now,” says Gerry Myers, Lambert’s coach at Crestwood High in Mantua, Ohio, “and see him hitting the split end from Streetsboro. Knocked his helmet and one shoe off.”

Oh, there are still middle linebackers—seven of them. They belong to the seven NFL teams that continue to use the 4-3 as their basic defense, but most of them are 60% players. They get the hook on passing downs, when the defense goes into its nickel. There’s the Bears’ Mike Singletary, the best of the bunch, but the rest of the names won’t quicken the pulse: Ken Fantetti, David Ahrens, Neal Olkewicz, Bob Crable, Bob Breunig, Fulton Kuykendall—all good steady workers, but there’s no magic there. So can you blame Lambert for trying to recapture a little of the old imagery, some of the old glamour—and terror—that went with the position?

Actually, if you look at Lambert’s career with the Steelers you find a remarkable collection of big plays in big situations, but no trail of bloodied and broken bodies; you find very little to justify all the adjectives of mayhem that give writers so many easy off-day features. Lambert hits hard, of course. Always has, ever since his high school days.

“After a while teams would stop running curl patterns in front of him,” says Gerry Myers, his coach at Crestwood High in Mantua, Ohio. “I can close my eyes now and see him hitting the split end from Streetsboro. Knocked his helmet and one shoe off.”

As for the missing front teeth, they were the victims not of the thundering hooves of Pete Johnson or Earl Campbell, but of the head of Steve Poling, a high school basketball teammate. Poling’s head collided with Lambert’s mouth in practice one afternoon.

“Jack was very sensitive about it at first,” says his mother, Joyce Brehm. “Once, when he was swimming in an old gravel pit after school, he lost his bridge, and he stayed out of school until the dentist made him a new one.”

Then there are the feet, the way he’d pump them up and down before the ball was snapped, a picture of intensity. He got away from that after his first few years.

“I’ve had people tell me I’m not playing as hard as I used to because I don’t pump my feet up and down,” he said in 1978. “I’d hate to think I only played hard when I pumped my feet.”

Four incidents, fairly evenly spaced, helped nurture and feed the Lambert image. First there was the Cliff Harris affair in the Super Bowl after the ’75 season, Lambert’s second year. In the third quarter the Steelers’ Roy Gerela missed a 33-yard field goal. Harris, the Cowboys’ free safety, tapped Gerela on the helmet and said, “Way to go.” Lambert flung Harris to the ground. No flag was thrown, but referee Norm Schachter was on the verge of kicking Lambert out of the game. Lambert talked him out of it.

“Jack Lambert,” Pittsburgh coach Chuck Noll said afterward, “is a defender of what is right.”

Then there were the three Brian Sipe incidents, during the ’78, ’81 and ’83 seasons, three set pieces from the same script. Each time Lambert hit the Cleveland quarterback as he was releasing the ball. Too late, decided the referee, who was Ben Dreith the last two times. Each time Lambert got mobbed by the Browns’ bench, each time he was flagged, and twice he was ejected from the game and fined by the league.

After the ’78 hit he spent 20 minutes in Pete Rozelle’s office. Lambert explained that he had crossed both arms in front of him to soften the blow. The hit was still late, Rozelle said.

“I asked him, ‘How about the guys who came off the bench and mobbed me?’ ” Lambert says. “ ‘Were they fined?’ He said, ‘No, but they got very strong warnings.’ ”

In the dressing room after the ’81 game, the writers asked Lambert about the play.

“Dreith said I hit Sipe too hard,” Lambert said.

“Did you?”

“I hit him as hard as I could.”

Noll defended Lambert in ’83. He said that what the Browns did to Lambert on the sidelines was “criminal ... they kicked him where no young man should be kicked.”

In the locker room the writers asked Lambert about it again. Same play, same ref. It was getting a bit old. He capsuled the situation in his terse and hard-bitten style: “Brian has a chance to go out of bounds and he decides not to. He knows I’m going to hit him. And I do. History.”

A few months ago Lambert was still sore. “I was seriously thinking about changing my uniform number after that game,” he said. “I felt that I’d been thrown out because I was No. 58, because I was Jack Lambert. At the Pro Bowl this year I was talking to one of the officials. He said, ‘I saw films of that Cleveland game. What did you do?’ I said, ‘Hey, no kidding.’

“But Brian was the quarterback. He lay on the ground like a sniper had shot him, so they threw me out. It’s big entertainment now, protect the quarterback, $200 to your favorite charity.”

And that’s basically it. Four incidents. And the image grew, fed on itself, took hold. Sometimes Lambert helped it along.

“After the Harris thing in the Super Bowl,” he says, “I thought it would be a great chance for Cliff and I to do something commercially in the off-season. My agent talked to his, but he wouldn’t go along with it.”

Sometimes his teammates chimed in. “Jack likes to hit hard,” Rocky Bleier said at a charity roast in 1980. “He likes to inflict a lot a pain ... and that’s just when he’s out on a date.”

Count Dracula, Mad Man Jack—it used to bug him. “It’s beginning to get out of hand,” he said in his fifth season in the league. “All that stuff upsets me, because I’m not a dirty football player. I don’t sit in front of my locker thinking of fighting or hurting somebody. All I want to do is to be able to play football hard and aggressively, the way it’s meant to be played. But when someone deliberately clips me or someone comes off the bench and tries to bait me, like they did in Cleveland, well, I’m not going to stand for it. I will be no man’s punching bag.”

Sometimes he looks at it philosophically. “Oh hell, it’s just an image,” he says now. “Adults are fooled sometimes, but kids see right through it. Kids are tough to fool. Besides, it works to my advantage in the camp I run. When I tell the kids to keep quiet and go to bed, they listen.”

“His first step is never wrong, his techniques have always been perfect,” says Russell. “His greatness has nothing to do with his popular image.”

“One night we were sitting around watching the Steelers on Monday night TV,” says Fred Paulenich, who teaches at Crestwood and remembers Lambert from his high school days, “and they were doing those little spot intros, and Jack introduces himself as ‘Jack Lambert, Buzzard’s Breath, Wyoming.’ I could see all of Mantua sitting up at that one. Cosell even repeated it later, and I said, ‘Oh my God, he believed it.’ ”

“I heard about it,” Lambert’s mother says. “The people I talked to didn’t see the humor in it. I didn’t either.” She pauses for a moment. “You know,” she says, “Jack reads all that stuff about himself, and I think he feels he has to live up to it in some way.”

Russell, a successful businessman in Pittsburgh these days, shakes his head when asked about the Lambert image.

“Tough, raw-boned, intense,” Russell says, “that’s the way he’ll be remembered, but I’ve seen a lot of guys like that come into the league. No, Jack’s a whole lot more. The range he has ... they put him into coverage 30 yards downfield. They gave him assignments that the old Bears or Packers never would’ve dreamed of. He brought a whole new concept to the position, and that’s why, for me anyway, he’s the greatest there has ever been. His first step is never wrong, his techniques have always been perfect. His greatness has nothing to do with his popular image.”

The image. Close your eyes and you can see Lambert ranging from sideline to sideline in the old 4-3 days, a big wingless bird, half an inch over 6'4", barely 220 pounds, always squared up to the line, always around the ball. He has made the Pro Bowl in nine of his 10 years and leads active players for appearances. He missed out only in his rookie season. He has led the Steelers in tackles all 10. They didn’t keep stats for tackles and assists in the old days, but he probably has more than any Steeler ever.

“Last year, when the Bengals beat Pittsburgh, they ran off 75 plays,” says Mike Giddings, who operates a private scouting service and grades all NFL players. “Lambert was in on 31 tackles. He had 22 at halftime. I don’t see how his body could stand it.”

The Hall of Fame is certainly in his future, but he’ll have to wait his turn. Jack Ham, Joe Greene and Terry Bradshaw, his teammates from Pittsburgh’s Super Bowl era, will probably get in before him. And he’ll most likely still be active when Franco Harris has retired to begin his five-year wait for enshrinement.

“I don’t like to speculate on something like that,” Lambert says. “But you know, it’s a funny thing. I grew up right down the road from Canton, and I’ve been to the Hall a few times, and one thing always struck me, how few people have made it—123, and 15 or so weren’t active players.”

* * *

Mantua, pronounced man-tu-way, is situated 30 miles due north of Canton. It’s a town of some 1,200, living off light industry and the small dairy farms that dot the countryside southeast of Cleveland. The folks in Mantua are impressed by a famous citizen, by a Jack Lambert who goes off and makes a name for himself, but they’re not dazzled. Still, in 1980 they renamed Crestwood High’s football stadium Jack Lambert Stadium, an honor that Lambert calls “the greatest I’ve ever had in my life.” His mother remembers the night all too well. “I got my first and only traffic ticket while I was on my way to the ceremony,” she says. “Only in Mantua would they give a ticket to the star’s mother on the way to the dedication. Mr. Post gave it to me. He didn’t recognize me and I didn’t say anything.”

Lambert grew up working summers on his grandfather’s farm driving a tractor, baling hay, doing odd jobs. “Farm-boy strength,” his mother says. He brushes off his achievements at Crestwood, where he earned nine letters in football, basketball and baseball. “Small school district,” he says. “Mostly farmer kids.”

“You have to understand this area,” says Bill Cox, Lambert’s old basketball coach. “Those 6'7", 260-pound high school football players you hear about, you just don’t see ’em around here. When Jack played there was a 6'8" center on the basketball team named Denver Belknap, and he was the freak of northeast Ohio. Jack was 6'3½" in his senior year, and I don’t think Crestwood’s had anyone much taller since.

“Things like drugs were unknown in that era. Sometimes maybe a couple of kids would sneak off and drink a beer in the back of a car—all farmer kids like beer—but that was the extent of it. I remember once the kids came to me and said they saw Belknap smoking cornsilk while he was driving a tractor. ‘What’s cornsilk?’ I said. That was how much we knew.”

From his mother, who’s 5'8", Lambert got his height; from his father, now a plumbing estimator in Cleveland, his square and exaggeratedly wide shoulders. Lambert’s mother pulls out a sixth-grade class picture from Shalersville (Ohio) Public School, where she and Jack Lambert Sr., were classmates. Jack Sr. is in the front row, a blond, wide-shouldered little boy with the same tight-lipped, slightly sardonic smile that marks Jack Jr. It was his father’s side of the family that also supplied Lambert with toughness, or at least a good share of it.

“My father’s dad played a little neighborhood football in Cleveland,” Lambert says. “I’ve got a picture of him in his old leather helmet on the wall of my study. But he was best known for his boxing. He fought under the name of Johnny Lemons because his mother didn’t want him to fight. They tell me he once fought Johnny Risko in Cleveland, even though he was little more than a middleweight and Risko was a heavy.

“He ended up as a store detective in Higbee’s in Cleveland. I know he was a guy with a short wick; he saw things right or wrong and that was it. Once he was driving in downtown Cleveland and my aunt was in the car. She was about 11 or 12, and they’d just been shopping. He stopped for a light and three or four drunks in the next car said something to my aunt. My grandfather never said a word, but he reached in one of the grocery bags in back and pulled out a wine bottle, busted it and opened up a guy’s arm, and that was the end of the argument.”

“I remember chasing Jim Brown one time to get an autograph,” says Lambert, “running after his car, a green Cadillac. I finally did get it. I’ll never turn down a kid for an autograph, but first he’s got to say ‘Please.’ ”

When Lambert was two years old his parents were divorced. He’d spend weekends with his father. Most of the time they’d play ball. A few years ago Jim O’Brien of The Pittsburgh Press asked Lambert if his parents’ divorce had affected him in any way.

“I’m sure it did,” Lambert said, “but I don’t think it’s the business of readers of The Pittsburgh Press.”

At Crestwood, where Lambert was a catcher and lettered for four years, they said that he had a great future in baseball and that he was good enough at basketball to play in college. But his first love was always football.

“I was a Browns fan. All the kids in the area were Browns fans,” he says. “We were only a couple of miles from Hiram College, where the Browns trained in the summer. Jim Brown was everyone’s favorite player. I remember chasing him one time to get an autograph, running after his car, a green Cadillac. I even remember the license plate, JB832. I finally did get it. I’ll never turn down a kid for an autograph, but first he’s got to say ‘Please.’ ”

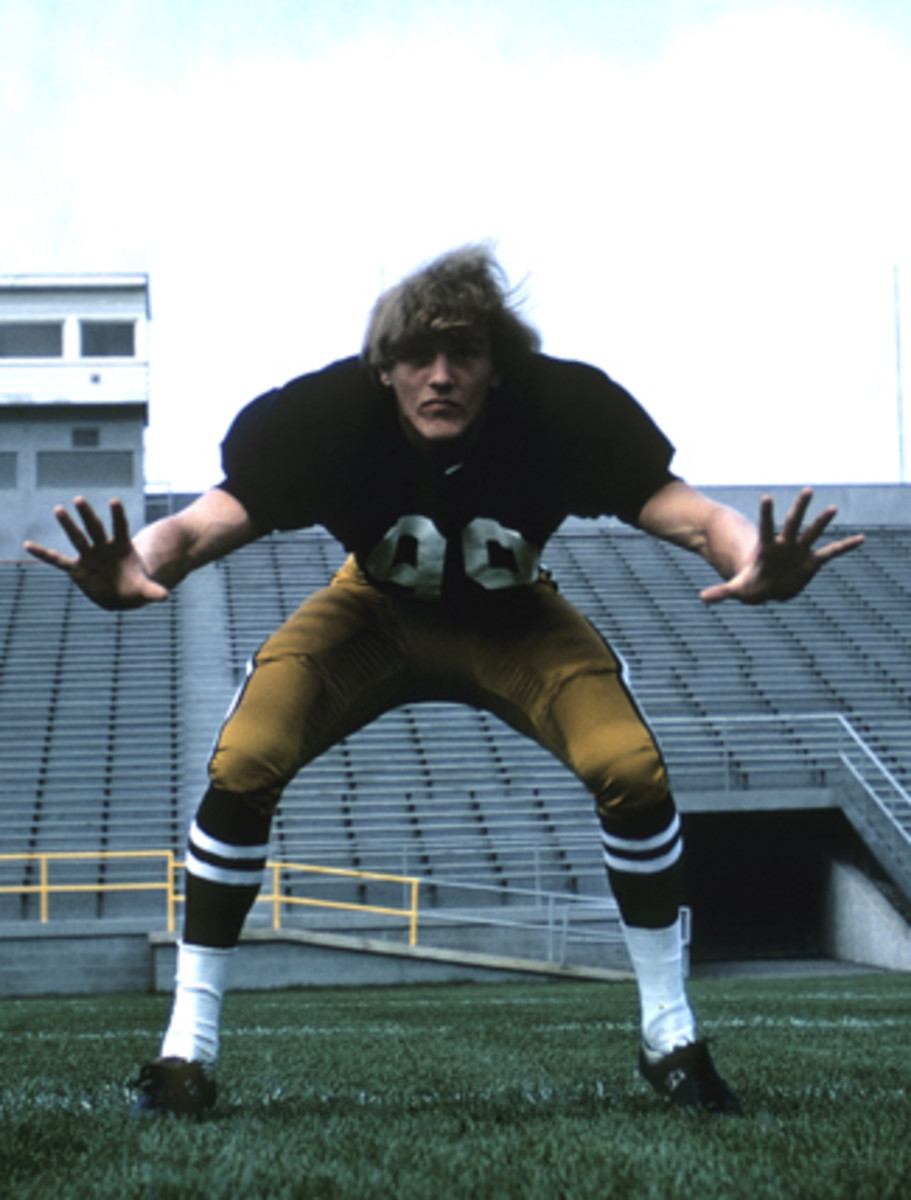

Lambert also remembers going up to his football coach after his freshman year and asking to get his number changed to 00.

“He told me, ‘If you want to wear a special number, you’ve got to be a special player,’ ” Lambert says. He got the number after his sophomore season, and it’s since been retired, along with the 99 he wore at Kent State, giving him a record for range of retired numbers that will never be broken unless they go into three digits.

He was a shrimp as a high school freshman and sophomore, with a cute blond crew cut. “We had a flower shop,” his mother says, “and one Easter we dressed him as the Easter bunny and made him deliver flowers. He was disgusted, but he looked so cute. He said, ‘Never again.’ ”

By his junior year he had begun to shoot up, and as a 6'3½", 170-pound senior he became a dominating force—in all his sports.

“He averaged 17.9 points and 13 rebounds in basketball,” Cox says. “People say, ‘Wow, Jack Lambert on a basketball court, he must have sent bodies flying,’ but he wasn’t like that. He was smart, technically very sound. He always knew what had to be done. In his senior year Kent Roosevelt High had a 6'5" kid named Andy Steigmeier who later made All-State and played for Ohio State, a real cocky kid. Before the game Jack said to me, ‘Can I guard him?’ Jack got four fouls on him at halftime, and the kid fouled out early in the second half and we won by a point.

“You’d never see Jack lose his temper out there. When he got mad he got real quiet. When he didn’t like a call he’d hold the ball maybe an extra second or two before he threw it back to the ref, but he wasn’t the kind of guy who’d throw a basketball up to the ceiling.”

In football Lambert played quarterback (“Handed the ball off mostly,” he says) and on defense he made all league as a weakside cornerback—squirmback, they called it at Crestwood.

“He was my fourth-fastest of four starting defensive backs,” Myers says. “He didn’t get his speed till he got to college, but no one ever completed anything deep over him. His first step was always correct. He always knew the angles. And God, would he hit ’em. First they stopped throwing curls in front of him, then they just stopped throwing to the split end in general.

“He was intense, dedicated. He used to say, ‘I don’t know where I’m gonna play someday and I don’t care, but I will play.’ He’d play in pain, too. He played against Field High his senior year with a sprained ankle, a deep calf bruise that was black and blue, a knee sprain and a thigh bruise that was starting to turn purplish-yellow. Oh yes, he also had a hip pointer that would have kept anyone else out of the game. Our wrestling coach, Frank DiNapoli, taped him from ankle to waist. We held him out on offense, but he went the whole way on defense and we won 20-0.”

Myers, who’d played tight end and captained his team at Miami of Ohio, tried to get Lambert into his old school. Miami’s coach was Bill Mallory. He told Myers that Lambert was too slow to play the secondary in college; maybe, if he got up around 220, he’d be a defensive end someday, but not at Miami.

“I told Mallory, ‘You’d better hope he goes outside the Mid-America Conference,’ ” Myers says, “ ‘because someday he’s gonna come back and beat you.’ He did, too, his junior year at Kent. Beat ’em on a goal-line stand. He made four straight tackles inside the two.

“But I’ll tell you the truth, I was worried. I mean if you can’t even get a guy into your own school, geez. Wisconsin toyed around for a while. So did a few MAC schools, but no one would give him a full scholarship.”

Cox finally swung the deal for him at Kent State.

“I knew their coach, Dave Puddington,” he says. “He’d been losing a lot of Ohio kids to other places. The only real blue-chipper he had was Don Nottingham [who went on to play fullback for the Miami Dolphins]. He asked, ‘What kind of a kid is Lambert?’ I told him, ‘Look, you keep complaining about losing solid kids. If you’re gonna gamble, this kid is the one to gamble on. He’s only 17 and he’s been playing against older kids. He hasn’t really started to mature.’

“He was still leery about Jack’s speed and his skinniness, but in the spring a kid from New Jersey got married and didn’t come back, and a scholarship opened up. Jack got it.”

A year later, in the Kent State alumni magazine, Puddington was quoted as follows: “We’ve got a tall, skinny kid named Lambert playing defensive end. Notts [Nottingham] nearly cuts him in half with his blocks, but he keeps getting up and going for the ballcarrier. When he puts on some weight and learns the position, he’ll be a terror.”

“He weighed 187 as a freshman, and even in his senior year, when he got up to 217, he couldn’t hold the weight,” says Denny Fitzgerald, Lambert’s defensive coach at Kent and a Steelers defensive assistant now. “He was 203 after the season.”

Don James took over as Kent State coach in Lambert’s sophomore year and, with three games left in the season, moved him to middle linebacker in the 4-3. But he was due to go back to defensive end as a junior.

“There was some transfer from Buffalo named Bob Bender who was going to be the middle linebacker,” Lambert says. “He was supposed to be the next Dick Butkus or something, but he quit two weeks before the season started, so they threw me in there. They had no choice. It was the greatest break of my life. Right away I loved it. Last time I heard about Bender he was a bodyguard for the Rolling Stones.”

* * *

The Kent State press book for Lambert’s sophomore season had included the prophetic words “lust for contact” in his bio, and by the end of his junior year the publicity department was listing his tackles and assists in its weekly mailings—19 and five against Miami, 15 and six against San Diego State. That year Lambert was voted MAC Defensive Player of the Year and MVP of the Tangerine Bowl, despite the presence of Tampa’s John Matuszak, the first player drafted by the NFL that spring.

The pros had a book on him, also some questions. Where do you play a skinny 6'4½" kid?

Rooney pulls out the Steelers’ old scouting file on Lambert. The reports run pretty much true to type: “Intense, great nose for the ball, needs to add weight....”

“My cousin Timmy, who’s head of personnel for the Lions now, was the guy most in his corner,” Rooney says. “He told me that the day he was up at Kent they had a quarterback who was evidently a dissipater, and he did something and they were going to throw him off the team. Lambert was the captain. He went up to Fitzgerald and said, ‘You can’t. You’ll wreck the team.’ Fitzgerald said, ‘O.K., but he’ll have to run a punishment drill.’ Lambert said, ‘I’ll run with him to make sure he does it.’ Lambert ended up dragging him through.

“Timmy told me that story one night, and next day I drove up to see him myself. The field was muddy. They were practicing in a parking lot, with cinders. Lambert dived at someone and when he got up, all these cinders were sticking to him. He went back to the huddle picking cinders off.”

In terms of defensive talent there has probably never been anything to match the Steelers’ first two Super Bowl champions. “We just shut people down, completely dominated them,” Lambert says. “Teams would just give up running the ball against us.”

The Steelers drafted him with time running out for their second-round pick. It had been between Lambert and UCLA linebacker Cal Peterson, who wound up in Dallas. Lambert was happy to go to a place only a 2½-hour drive away, but there was a problem. What position was he going to play? The left linebacker, Ham, was just emerging as a superstar. Russell, on the right side, had played in four straight Pro Bowls, and Henry Davis, the 235-pound middle linebacker, had been a Pro Bowler two years before. Lambert began driving to the Steelers’ office every weekend to watch films.

“I thought everybody did it,” he says. “But I guess that it was unusual, since the newspapers made such a big fuss about it.”

That was a strike year, 1974. Lambert got an extra-long look in camp. So did Mike Webster and Lynn Swann and John Stallworth, and a free agent named Donnie Shell. All of them wound, up as Pro Bowlers. The veterans returned, and Lambert backed up Ham for a while, but in the next-to-last exhibition game Davis went down with a nerve injury in his neck, and Lambert was thrown in the middle.

In terms of defensive talent there has probably never been anything to match the Steelers’ first two Super Bowl champions, the ’74 and ’75 teams. In the Pro Bowl following the ’75 season, seven Steelers were on the starting AFC team, including all three linebackers. Another Steeler was a backup, another had made it earlier and another, Shell, was a future. That’s 10 defensive Steelers with Pro Bowl credentials on one squad.

“We just shut people down, completely dominated them,” Lambert says. “Teams would just give up running the ball against us.”

“Bud Carson was the defensive coach, and having Lambert allowed him to do things that had been unheard of,” Russell says. “Bud had him covering the tight end all over the field. He’d assign him the first back out of the backfield. Normally the middle linebacker covered the second back, which is a piece of cake; he’s just a floater. But the first back, my God, it was thought to be an impossible assignment for a middle linebacker. He’d have Lambert making calls and changing the defense three, four, five times when we’d play a team like the Cowboys that kept changing their sets. No one ever tried to match the Cowboys call for call. Usually Dallas would get a team into some kind of simplistic zone, and that’s when Staubach went to work, but Carson would have us changing our calls as many times as they changed sets. Pure genius stuff. Once we changed six times. And Jack had to know everything, call everything.”

Against the run he’d read everything right, always get leverage and balance on the blocker. “There wasn’t an NFL center who could cut him off on a sweep,” Russell says. “He’d read and he was gone.”

Al Davis remembers a play Lambert made in the ’75 season’s AFC Championship Game against the Raiders. “There were seven seconds left and we were down 16-10,” he says. “We hit Cliff Branch deep down the sideline and he was going to lateral to Ted Kwalick, our tight end. Lambert read it and positioned himself on Kwalick to take the lateral away, and Mel Blount tackled Branch on the 15-yard line. It was a great play by Lambert, a great read, and it never showed up in the stats.”

In ’76 the Steelers were beaten by Oakland for the AFC championship when a plague of injuries hit their running backs. In ’77 they lost to Denver in the playoffs. Lambert had missed three games with a knee injury. He’d been a 39-day holdout in camp, over contract matters. A few people partly blamed the demise of the Steelers on him. He didn’t take it kindly. Eventually he signed a five-year contract for a reported $1.25 million, making him the highest-paid defensive player in the game.

“I reminded him of what he said when he was a rookie, that he’d play for nothing,” his mother says. “He said, ‘This is different.’ ”

The ‘78 and ’79 Steeler teams won two more Super Bowls. Lambert was still a young player, but by now he’d picked up an old-pro image, hard-bitten, no time for chitchat. In ’77 Houston had beaten Cincinnati to allow the Steelers to back into the playoffs, and a day before Pittsburgh’s first-round game Joe Greene announced that in appreciation the Steelers were sending each Oiler player an attaché case. Lambert threw his helmet into his locker in disgust.

“This is a bunch of junk,” he said. “We’re all professionals. We get paid to win.”

* * *

The week before the Super Bowl in Pasadena in 1980 was a downer. Winter rains had turned the practice field heavy and soggy, deadening the legs. The team had an air of defeat about it. One day after practice Lambert and a couple of teammates were having a beer in the Main Brace, the bar in their hotel in Newport Beach. A bunch of teeny-boppers spotted them.

“There’s Jack Lambert,” one of them said. “Hey, Jack, do you believe in astrology?”

No answer.

“What’s your sign, Jack? You know, astrology.”

“Feces,” he said.

The kids in Pittsburgh saw another side of him, though. So did the people who’d get him to make one of his rare banquet appearances—always unpaid.

“In the old days players would go into a place, tell a couple of locker-room stories, talk about the team, take the money and run,” he said. “I decided I wasn’t going to cheat people.”

“I always want to go to the ball and pursue all over the field,” Lambert says. “The old middle linebacker position is pretty much gone forever.”

So he began to talk about drugs, and senseless vandalism, about respect and the pride that he felt when he stood at attention before a game and heard the national anthem played. The audience would stare at him. Is this a put-on or what? Then they’d applaud. At one affair someone asked him what he’d do to the drug dealers. His reply was typically blunt. “Hang them by their feet in Market Square until the wind whistles through their bones.”

“I read about sports figures who say the idea of their having an impact on kids is overrated,” Lambert says. “I can’t believe that. I’ve had kids at my camp who I know damn well would listen to me before their parents and their teacher. We have a responsibility, and if I can keep one kid from going on drugs I’ve accomplished something.”

The remnants of the Super Bowl Steeler defenses are dwindling. Last year Ham retired; this year it’s Blount and Loren Toews. Only Lambert and Shell remain. And in 1982 the Steelers gave Lambert a partner at an inside backer spot, going to the 3-4. Jack didn’t like it.

“It was a change for me,” he says. “I was 30. I didn’t know how I’d adjust. Having to worry about cutbacks, well, it goes against my nature. I always want to go to the ball and pursue all over the field. This way is an efficient way to play the game and I accept it—but that doesn’t mean I like it.”

He doesn’t leave the field on passing downs. “If I did I’d start looking for another position,” he says. His range on deep coverages is still amazing.

“No matter where he plays, he is and always will be the hub of that defense, both physically and mentally,” says Cleveland coach Sam Rutigliano, whose Browns play Lambert twice every year. “To me Jack Lambert is the Pittsburgh Steelers.”

“The old middle linebacker position is pretty much gone forever,” Lambert says. “I still think that if you have four really good defensive linemen you could play the 4-3, but maybe that’s why we got away from it in the first place.”

He has three years to go on his contract, which he signed before the ‘82 season. He called it a “career ender.”

“He wants to be the best at what he does,” his mother says. “I think there will come a time when he’s not All-Pro anymore, and I’m afraid of that. I heard someone talking about an older player the other day and he said, ‘Yeah, that was back when he could play.’ I don’t ever want to hear that about Jack. He’s always said he’d play as long as it was fun. When he was home at Christmastime he didn’t look like he was having fun. I’d like to see him get out of it. He’s had a marvelous career—eight years in high school and college, 10 years as a pro. That’s a lot of beating for one body.”

“I’ve met some of the old linebackers,” Lambert says. “Bill George, Sam Huff. Huff has written me a couple of short notes. ‘I saw you play. I think you’re a fine linebacker.’ It was really kind and considerate. I met Ray Nitschke one time and we sat down and talked, about anything and everything. He walks stiff. Most middle linebackers do.

“It’s funny to see how different people take their playing days of old—Jim Brown making a big deal out of coming back because Franco runs out of bounds, Huff sending nice letters. Isn’t it enough that Brown is remembered as the greatest running back? I’d like to think I’ll be like Huff. I’d like to say I played the best I could. If somebody comes along and makes the fans forget about me, God bless him. I hope he makes more interceptions and tackles. I can’t envision myself 15 years from now being bitter about another linebacker.”

• PAUL ZIMMERMAN: For more great Dr. Z stories, visit his page in the SI Vault

“Once in the locker room,” says Jack Lambert Sr., “Jack told me, ‘You know, Dad, I feel like I’m in the wrong place at the wrong time. I belong with the Steelers of the ’30s and ’40s. Win or lose, I’m a Steeler.’

“The first year he was drafted I had a heart attack. I said, ‘God, please let me see his first year in professional football. Let me live that long.’ Here it is 10 years later and I’m still alive. Someone says, ‘Your son’s gonna be in the Hall of Fame.’ Here I go again.... God, please let me live to see that. Jack gives me something to live for.”

Comments, thoughts or memories about Dr. Z? Send them to us at talkback@themmqb.com.