Best of Dr. Z: The Long Way Up

This week at The MMQB is dedicated to the life and career of Paul Zimmerman, who earned the nickname Dr. Z for his groundbreaking analytical approach to the coverage of pro football. For more from Dr. Z Week,click here.

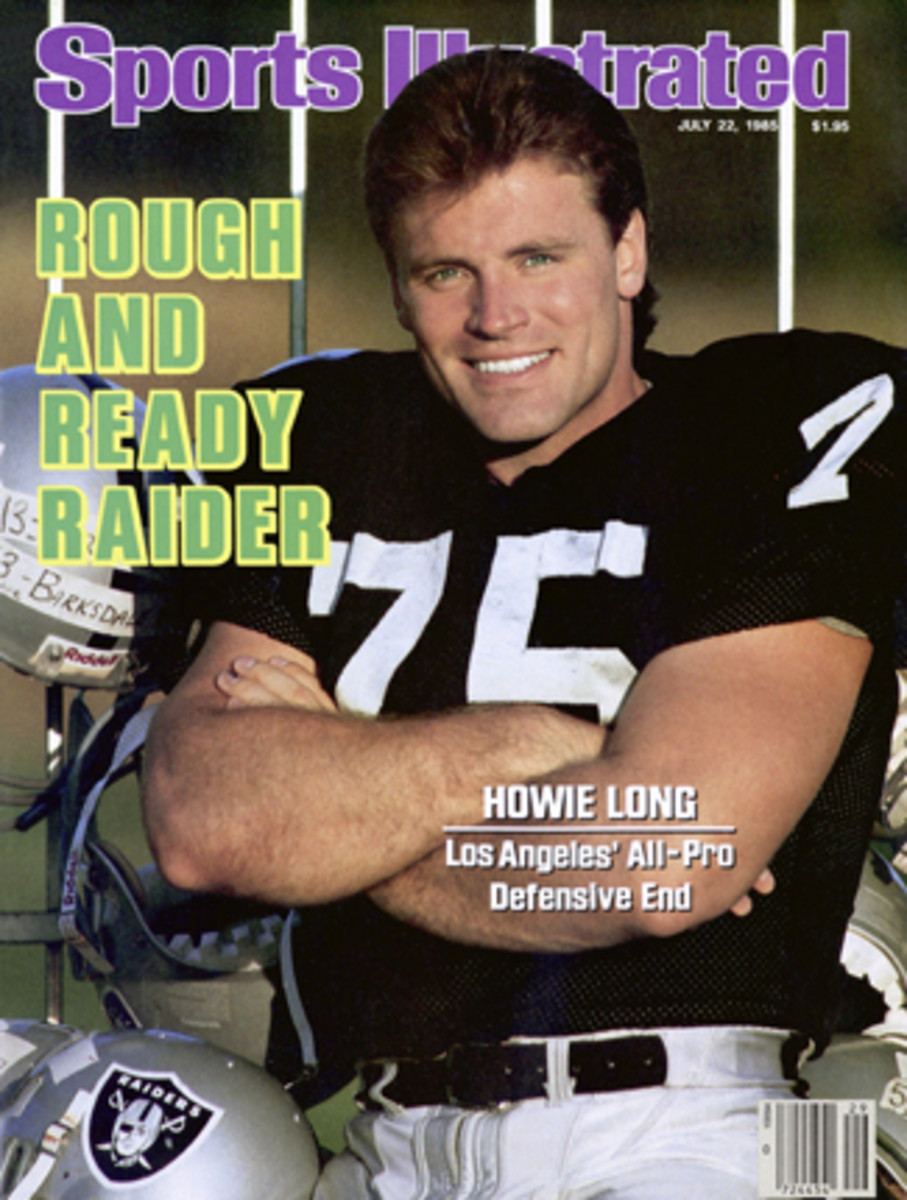

This story originally appeared in the July 22, 1985, issue of Sports Illustrated.

The headlights cut through the blackening gloom of the Charlestown section of Boston, and occasionally the car bumped a little as it ran over a patch of cobblestones or an abandoned trolley track. Howie Long slumped low next to the driver and watched the familiar streets slide by.

“The Neck,” he said. “This part is called the Neck. It's where the British landed the day before Bunker Hill. We used to go down to the playground here when we were kids and look out across the water and watch Chelsea burn. Every two or three years Chelsea burns.”

There was a pause. The car passed a series of dark, low apartments.

“The Projects,” he said. There was no further comment. Howie Long's sister lives in the area.

It was a bleak night in February and Uncle Mike Mullan was driving. Mike Mullan, a man as tough as his name. Bald, hard, he spoke in four-and five-word sentences, and his occasional snappers had an edge of bitterness. When he died of leukemia four months later, it hit Howie Long very hard. Uncle Mike was one of the four Mullan brothers. Long's four uncles who took charge of a maverick Charlestown street kid and turned him into a 6'5”, 275-pound All-Pro defensive end for the Los Angeles Raiders. Actually five Mullans had a hand in it.

The fifth was Long's grandmother, Elizabeth Hilton Mullan, whom everybody, including Howie, calls Ma. It was to her house, which she shared with Uncle Mike until his death, that they were driving on this winter night. Every year Long leaves his home in Redondo Beach, Calif., and comes back to Charlestown. It helps him keep things straight—where he is now, where he has been.

The car turned off Main Street onto Albion Place to No. 7, halfway up a hill that leads to a dead end. It's a two-way street with one lane. If you meet another vehicle on the way up, you back down and try again. Imitation gas streetlights provide a kind of antique touch.

Parking is no problem on Albion Place—if you live there. People don't park in front of someone else's house. An occasional stranger who makes that mistake doesn't make it again. Once, a couple of off-seasons ago, Long, with out-of-state license plates on his car, parked in front of his grandmother's house at 7 Albion Place and someone ripped off his stereo. It made headlines in the Boston papers and provided a lively topic for the interview sessions before the Raiders-Redskins Super Bowl.

“They wrote that I came from the slums, the ghetto, Gangland, U.S.A.,” Long says. “It became a locker room joke. The people here didn't think it was very funny. They were offended. They're very proud people, working-class people, Irish mostly, and very close. They're suspicious of outsiders, and that's what I am now, an outsider. You'd think I'd be a favorite son in Charlestown. I'm not. I'm not a hero. I didn't play my football here. I left.”

Heroes played for the Townies, the local semipro team in the Park League. The games were down by the Neck. Jack the barber coached them.

Playing football held no appeal for Long as a child. He could run fast and was big, too big. When he was nine he weighed 120 pounds. When he was 11 he was as big as the 13-and 14-year-olds. His uncle Billy, and then his cousin by marriage, Bob Murray, got him onto the Pop Warner teams they coached. He didn't stick around—for good reason.

“I was C-team age and A-team weight,” Long said. “I didn't feel like going out there and taking a daily beating from kids two and three years older.”

There was another thing, though, and it has been the dark shadow that has followed Long throughout his life. No confidence. Fear of failure, fear of being humiliated. On the street it was no problem. He could play street hockey, the No. 1 sport in Charlestown—“ball hockey,” they called it—and he could play basketball and baseball in the playground, but football was different. It was organized, the real thing, uniforms, adults to yell at you, everybody watching. Pressure. The downside potential was too great.

Even as he climbed the football ladder, conquering each plateau as it came, the fear never left him. Two years after he finally committed himself to football he was a high school all-stater, seriously recruited by major schools. But to him, big-time college football meant only the chance for big-time failure.

“I'd just finished reading Meat on the Hoof, by Gary Shaw, where he tells about what they did to guys at Texas when they wanted their scholarships back,” Long says, “how they ran them off the team and put them through torture drills. I was terrified. What if I can't play?”

He signed a letter of intent at Boston College and immediately had second thoughts. “What happens if he gets hurt?” his uncle Billy asked a BC coach.

“The guy told me, ‘Well, we only have so many scholarships a year,’” Bill Mullan says. “ ‘He'd lose it.’ So Howie switched and went to Villanova, where they offered him a four-year.”

By his senior year he was good enough to be chosen for the Blue-Gray all-star game in Montgomery, Ala.—as a late entry. Joe Restic, the Harvard coach and one of the assistant coaches for the Blue team, needed a spot on the roster filled. He chose Howie, who had been a high school teammate of his son, Joe Restic Jr.

Howie is 25 with two years of All-Pro behind him, a wife who has completed two years of law school and a healthy baby son named Christopher Howard Long. It’s all there ahead of him, a life of infinite promise.

“I roomed with Colin McCarty, the middle guard from Temple who'd driven trucks with Joe Klecko,” Long says. “No one talked to us. No one offered to take us out to dinner. It was the worst week of my life. They had a banquet the night before the game, and they introduced me to the guy I was going to play against, Zach Guthrie of Texas A&M. Texas? I'd never met anyone from Texas in my whole life. I'd seen him during the week. Great big guy, two-tone shoes, leather jacket, leather cap, toothpick in his mouth all the time. Never said a word. They announced his name at the banquet, then they announced me as the guy who'd be playing against him, and Frank Howard, the old Clemson coach who was emceeing the thing, pointed his finger at me and said, ‘That's you, boy.’ Scared? Hell, yes, I was scared.”

And when the game started, when Long got his first taste of combat, the fear melted, and it was just football. He blocked a punt and pressured the quarterback all day. When it was over he was named defensive MVP. He said hello to his grandmother on national TV afterward and added, “Ma, it stinks here. I want to come home.”

In his first training camp with the Raiders the fear came back. “I thought I stunk,” he says. “I had no confidence—none. I couldn't understand why they'd drafted me in the second round.”

He remembers lining up for his first live-contact drill and looking across the line at the glare of 300-pound Artie Shell. “I thought, Oh my God,” Long says.

He sits in his grandmother’s kitchen in Charlestown, his great frame crowding the room, his face alight and open as he tells these stories. It’s the face of innocence, an Irish minstrel boy’s face transported to the body of a massive grown man. This magnificent body, combined with those clean, chiseled good looks, already has the Hollywood talent scouts buzzing. Now where is there a part for a 275-pound choirboy? He is 25 years old with two years of All-Pro behind him, a wife who has completed two years of law school and a healthy baby son named Christopher Howard Long. It's all there ahead of him, a life of infinite promise, and yet almost every story he tells about himself, every anecdote, has an undercurrent of despair. It’s not me, he seems to be telling you, this isn’t really me that you see here in front of you.

Long achieved celebrity status in 1983, his first All-Pro year. Writers who met him for the first time during Super Bowl week in Tampa in the tent put up for mass interviews were surprised by his soft-spoken, articulate manner and his wry, often hilarious way of expressing himself. One morning, with 30 or so writers crowding his little interview table, Long tipped his chair back, stared up at the top of the tent and proceeded to let loose a stream of consciousness that could become the definitive word on the surrealism of Super Bowl press days:

“Give me a day to die.... Are we in Kansas yet, Toto? I don't know where I am.... Oh God, I'm in a tent....”

Some kid, huh? Bright, great talent.

“Do you know what I was thinking the first day they had those press interviews?” he says. “I was thinking, Every player has his own table. What if nobody's at mine? How will I handle the embarrassment?”

Fear. Self-doubt. Curt Marsh, the Raider guard who roomed with Long at their first minicamp, remembers waking up in the middle of the night to see a frenzied Long wrestling the TV set off the wall and preparing to throw it out the window. “His eyes were wide open, and they had the glassy look of a maniac’s,” Marsh says. “I thought, Who am I living with? Then I realized he was asleep. I called, ‘Howie! Howie!’ There were nights when I saw him get up in his sleep and start fighting people. Once he almost went through a window....”

Long's wife, Diane, says, “He was always like a volcano about to erupt, always driven. Everywhere we went, he thought people were staring at him.”

The story starts in Charlestown, one of the oldest towns in Massachusetts—it was settled in 1628. There are a few Colonial landmarks in Charlestown, but the pervading look is early industrial revolution, dark, soot-stained brick walls, abandoned factories, and the great gray shadow of the Projects. Long’s first memories are street memories.

“There's the Bunker Hill Elementary School, the first school I went to,” he said as the car cruised the area last winter. “And this is Hood’s the dairy, where my grandmother worked for 26 years. We used to play touch football on this little 10-foot-wide patch of grass between the dairy and the street. If you could catch a down-and-out pass on that field you were a serious player. And that’s Eden Street Park across the street. See those three kids on the bench? That was me 12 years ago. Here’s the place, Decatur Street, under the highway, where I got hit in the head with a bat. Me and this kid were hitting rocks, and as I bent down he cut loose with his home run swing and it caught me in the forehead. I didn't go down. I went to one knee. I had a lump this big. I walked home. Nobody was there; I went to bed.”

“Howie was always bigger than everybody else,” says his cousin Michael Mullan, a brewer for Anheuser-Busch, “but he wasn't tough. When you’re that big and you ain’t tough you’ve got a problem. Everyone wants a piece of a big guy. Kids would pick on him. I used to have to force him to fight. He’d be crying; he wouldn’t do it. I gave him a choice—fight them or get smacked by me. After a while people left him alone.”

“I felt like the orphan everybody took in,” Howie says. “Do you know what it’s like to be 12 years old and not wanted?”

Those memories haunt Howie Long to this day. The bitterness never leaves. “My cousin talks about throwing me into the street at seven or eight years old to defend myself,” he says. “Can you imagine what that’s like? What seven-year-old kid wants to fight?”

At home there was no one to turn to. The Long family lived with his grandmother and Uncle Mike at 7 Albion Place, but his father, Howie Long Sr., was pulling long hours loading milk for Hood’s Dairy, and his mother was bedridden most of the time, suffering from periodic attacks of epilepsy. Howie’s four uncles, the Mullan brothers, had their own kids to worry about. There was only his grandmother, Ma, to feed him and clothe him. She knew what it was like to grow up alone. She was an orphan who finally had been rescued from a Catholic children’s home in Yonkers, N.Y., by her aunt, Nellie O'Neill of Charlestown. She married Michael Mullan from Londonderry in 1925. He died of cancer in 1955. “He’d been a major in the IRA,” Long says. “He lived next to the police station, and they tell stories about how he used to pass information along by a series of smoke signals from the chimney.”

When Howie was nine, the Longs moved out of his grandmother’s home to a house at 170 Bunker Hill St. “From that minute on, everything went downhill,” Long says. “No one ever cooked in our house.” He remembers sneaking over to 7 Albion Place, where his grandmother or his aunt Edie would feed him. Two years after the move his parents separated; a year after that they were divorced.

The memories remain, always dark, always haunting. He says that on the day the divorce went through, his mother “kind of went crazy” and went after his sister. He broke up the fight. After the separation he remembers his mother dragging him through the neighborhood at night, trying to find his father, hoping to catch him with another woman.

When the Raiders played in the Super Bowl in Tampa, the Boston Herald found Long’s mother in Port Richey, Fla. She had remarried and retired. They took a picture of her with rosary beads in one hand and a picture of Howie in the other. “Mother’s pride...” the caption read.

“A reporter from that paper called me up,” Long says, “and asked me if I would get on a conference call with my mother. They wanted to do a This Is Your Life kind of thing. I told him, ‘Don't you ever call me again.’”

After the divorce, the court had awarded custody of Howie, then 12, to his mother. “That was just their ruling, but nobody fought for custody. No one wanted the responsibility,” he says. “Eventually I wound up back at my uncle Mike’s house. I felt like the orphan everybody took in. Do you know what it's like to be 12 years old and not wanted?

“I would have liked to have lived with my dad, but when they got divorced he was working as a day laborer, sleeping in his car at night. Then he lived in a rooming house in City Square. He’d had a terrible life. He’d spent 13 years in an orphanage in Salem. Once we drove by it, an awful-looking place with barbed wire outside. As a kid I remember my father waking up at night in a cold sweat, ready to defend himself.”

Howard Long Sr. had moved back into 7 Albion Place and lived with his ex-wife’s mother and brother for nine years, until April 13 when he remarried and moved to East Boston.

He describes his relationship with Howie as “cordial, but we'll never be as close as we should be because of what has happened in the past. I’m not proud of what happened, but what could I do? I was struggling.”

He is in his late 40s, youthful looking for a man with a 25-year-old son. Howie owes his height to his father, who stands 6'8” and weighs 230, with black hair and sharply defined features. Sitting in the Mullans' kitchen, his hands gripping a cup of cold coffee, he speaks in subdued tones as he tells a story of Gothic horror about the Massachusetts of his boyhood.

“I lived with foster parents until I was four,” he says, “and then I was sent to Plummer Farms School in Winter Island near Salem. It was a terrible, terrible place. You did 10 hours of farm work a day and two hours of school. There was one teacher for the whole place. I was in the sixth grade at 17. There was no talking allowed inside the building. If you were caught talking, they made you hold your hands out, and you were beaten with a leather strap soaked in kerosene overnight. The kids who were too big for that were punched in the face. When I was 17, I was given a choice of staying in the home or going into the Army. I jumped at the chance. I'd never seen a dollar bill until I went into the service, never talked to a girl until I was 18. I met Peggy Mullan at a record hop in Charlestown as I was rotating out of the Army.”

He studies the coffee cup and his hands tighten. “Seven of us went into the service,” he says. “Six of them got dishonorable discharges. I was the only one who didn’t. I’ve only met one guy who was in the home when I was there. He was a bum. I saw him on a bench in Boston Common.”

He pauses again. “You know,” he says, “there was a time when Howie and I almost didn’t talk at all. I’m very happy for him now, for what he’s done.”

It's a life that could have gone in almost any direction, but underneath it all, underlying the bitterness and despair, runs a strong current of self-preservation.

“I never fooled around with drugs, and I was never an outlaw or a punk,” Howie says. “Drugs scared me. I thought that if I did any kind of drugs I’d die. It was such an easy choice. It was as if someone said, ‘Hey, kid, do you want a hot-fudge sundae, or do you want to hold your hand over a fire?’

“I was a street kid, but that meant hopping a ride on the back of the MTA down to Revere Beach—that's the beach that's made out of concrete—or sneaking into the Boston Garden to watch the Celtics or the Bruins. We had our whole plan of attack drawn up like a battle plan; we'd scratch it in the dirt. I'd cut school and go over to the Lori-Ann Donut Shop and eat doughnuts. I got a job at the pet store near Lechmere, unloading fish tanks. They gave me $10 for unloading a full long-bed truckload. I never broke a fish tank. When I asked for a raise, I got fired.

“My uncle John was a cop at the time, and he got me a job at this bar, the Rusty Scupper, sweeping up. I was 13, and I looked 16.1 stood 6'1”, and I had this little broom and dustpan, and the place would be packed and I'd have to bend over and go around people's legs—‘Excuse me, sir.’

“I loved it. They gave me a striped rugby shirt. It said Rusty Scupper on it, and I’d take it to bed with me. To me it was the Cadillac of sport shirts. My idol was a bouncer with a cast on his hand, a guy named Topper Rogers. He’s a Boston cop. I wanted to be like him. Anyway Ma, my grandmother, came down and made me get out of the place.”

By the time Howie was 14 and ready for his sophomore year in high school, a major problem had developed: He had become a truant. No classroom could hold him. He had missed 45 consecutive days of school. The busing riots were a convenient excuse, for many parents were hesitant about sending their kids to school. But Howie Long needed no excuses to stay away from class. There was too much going on outside...fish tanks to unload, an occasional $20 to pick up longshoring on the docks when he could convince them he was 16. The Mullans had a conference. What should they do with this overgrown kid?

He could stay with Uncle George or Uncle Mike in Charlestown, but that didn't seem likely to work. It would just be more of the same. There was Uncle John, the cop, a solid officer who had once won the Medal of Valor for saving his partner's life. Uncle John had moved out of the area. “I was the social climber,” he says. “I moved to South Boston.” But, no, his hours were too irregular. Then there was Uncle Billy, a supervisor with the Boston Housing Authority, a star for the Townies, who had played service football in France. He ran his house with the same military discipline he had learned in the Army. He lived in Milford, Mass., a suburban community 20 miles to the southwest, in a house that was crowded with two of his own children and two that he and his wife, Aida, had adopted. There were no luxuries, but Uncle Billy looked like he might be the answer for a truant teenager.

The family had already tried to enroll Howie in a vocational course to train him to be an electrician, but he had been turned down mainly because of those 45 missed days. Uncle Billy said he would take the kid, but he would have to obey the house rules. They packed a suitcase for Howie, and Uncle John took him downtown, bought him his first suit, and sent him to the suburbs.

The night before a game he locks himself in his room with two cheeseburgers, a dozen iced teas and two reels of film. “If I don’t look at films the night before, I feel naked the next day,” Howie says.

Milford, Long says, was “high school, U.S.A. A beautiful place. They had cheerleaders, grass fields. I didn't know there was grass on the other side of the hill. I thought every place was like Charlestown. The first time I saw it, it was intimidating because it was so beautiful. The kids called me 'the Bostonian.' As an out-of-towner, I wasn't well received. I didn't have the kind of clothes the other kids had. I didn't have any parents in the booster club.”

But Milford also had something else, a very dedicated coach named Dick Corbin. The first time he got a look at the 6'2”, 200-pound Long he suggested that he come out for football.

Corbin, who's the offensive line coach at Harvard now, says Long was a “survivor” as a sophomore but had become a “player” as a 6'3”, 235-pound junior tackle. In the winter between those seasons he played basketball and in the spring he threw the weights. The football team went undefeated his junior year and beat Pittsfield, 42-7, in the state championship. By his senior year, recruiters already had a pretty good handle on him.

“He broke his ankle on the first play of our second game,” Corbin recalls. “The doctor said it was a four-to six-week injury. Howie said, 'Coach, my life is over.' In three days he had the cast off, and I saw him jogging around the field by himself, limping actually, and two weeks later he played.”

In the classroom his dedication wasn't as evident. “When I first got there the teacher said, 'O.K., class, write a short story on your vacation.'” Long says. “Vacation? What vacation? I didn't even know how to start it.”

He began cutting classes, and finally Corbin turned him over to his wife, Ruth Ann, an English and math teacher, for special tutoring.

“He was bright, you could see that right away,” she says, “but he'd never had any discipline. In Charlestown he'd just been passed along. The interesting thing was that he always spoke with perfect grammar, even though he had no formal knowledge of it. That was probably his grandmother's influence.

“He let things slide, though. He'd show up an hour late for our appointment; he hadn't done the work. One day I told him, 'I can't work with you.' He was shocked. Everyone had always made allowances. After that he was O.K.”

Life at home, according to Long, was a series of groundings. Those were Uncle Billy's traditional punishments, usually for missing the 9 p.m. curfew.

To this day, Long perceives Uncle Billy as a man of stern and unbending principle, but that doesn't give the whole picture. There's a fine strain of humor in the man, and underlying all is compassion, always great compassion. In the Mullan family Uncle Billy's house was the refuge for wayward relatives.

“That grounding was about Matthew's 40th life sentence,” he says, calling Howie by his middle name, “the sentences to run concurrently. You know there were times when he wouldn't talk to me for two or three days. But the end of it is, look how he turned out.”

Villanova received Long with these words from head coach Dick Bedesem: “He's unquestionably the finest recruit that our coaching staff has signed since we've been here.”

Long was a big fish in a little pond. The Wildcats had losing seasons his first three years. “No film room,” he says, “no reporters in the locker room; Ivy League level without Ivy League wealth.”

Diane Addonizio, a classical-studies major from Red Bank, N.J., met Howie Long in her freshman year when he was a sophomore. She recalls him as being moody and hard to know—“but attractive, boy was he attractive. I'd never met anyone that big who was that good-looking.” The first real date they had was when Howie invited her to his room to watch an NFL game on TV.

“A little 12-inch, black-and-white TV that my grandmother gave me,” he says. “A TV with lines on it and a coat hanger for an antenna. We watched a Dallas game. That's when they were still experimenting with Randy White at linebacker. On one play he got a running start and wham, he knocked the ballcarrier's helmet off. I started cheering. 'Wow, did you see that!' Diane must have thought I was nuts.”

“Howie wasn't one of these guys who's too cool to have idols,” says Diane, who married Long in June 1982. “He had pictures of Matt Millen and Bruce Clark from Penn State on his wall, and Mike Webster and Jack Lambert of the Steelers, and Joe Klecko from this area. Once he took me to a powerlifting competition at Villanova, and after we sat down he nudged me and said, 'Don't look around, but Joe Klecko just showed up.' He was absolutely in awe.”

It took her some time to finally understand this strange, moody young giant she was so attached to. “He didn't send me a Valentine's Day card when we first started going together. That upset me, and I told him so,” she says. “Then he explained how holidays never meant anything special to him. At Villanova when everyone went home for the holidays or the summer he was always the guy who stayed in the dorms. You know how a child's bed is special to him? Well, he never had his own. It was always a couch or something, while he was bouncing around from relative to relative. He was always living out of a suitcase, he always had his possessions on him. It took me awhile to understand that.”

NFL scouts who came to test Long after his senior year saw another side of his character: He was always willing to work out, to run, to test—at any hour of the day or night.

“The Patriots worked me out in the snow,” he says. “They plowed the field. I ran 40s and 20s, did a vertical jump. I asked the guy for a pair of turf shoes. He gave me a Patriots key ring. I kept it. I thought it was the greatest thing in the world.”

He was rated as a third-or fourth-round draft choice, but after the Blue-Gray game his stock rose. The Raiders sent their defensive line coach, Earl Leggett, to Villanova to work him out. “Earl had me set a couple of times and plant and come upheld 20 yards, and then he left,” Long said. “I thought, Well, that's one team I can forget about, and I went up to my room and watched Leave It to Beaver.”

“I had seen his Blue-Gray films,” Leggett recalls, “and we knew he'd run a 4.75 forty, but when you got around him you could feel the damn power and energy. You could just feel the brute strength.”

Long finished his college career at 251 pounds. When he showed up at the Raiders’ first minicamp he weighed 297, “just a biscuit away from 300,” he says. “I thought everyone had to weigh 290 in the NFL. Earl looked at me and said, 'What happened to the guy I drafted?' “

When the regular camp opened, Long found himself across the line from Art Shell. “It was the first pit drill,” he says. “I had checked out the line, and I saw that Matuszak was going against Lawrence, and Kinlaw against Dalby and Dave Browning against Shell, and I was going to get Lindsey Mason. I was getting ready for Mason when Shell came up and Earl said, 'Browning, step out of there, I want to see Long against him.' I thought. He's going to kill me. And he almost did. He hit me so hard he split the top of my right cheekbone and at the same time gave me the fists in the stomach. It was the most devastating pop I ever got in the NFL. My cheekbone still lumps up every year in training camp in the same spot.”

In 1981 he was 21, the second-youngest rookie in the NFL, Houston cornerback Bill Kay edging him by four days. “Howie was the greenest of the green,” Leggett says. “He didn't know nothing about playing the game.” Leggett called him “My pro from Villanowhere.” Each scrimmage, each game, became a death struggle. Eventually, all of Long's fears crystallized into one overwhelming urge to get the guy opposite him before he could deliver another dose of the Artie Shell treatment.

The rookies gave Long the nickname Caveman. The veterans were amused by him, by his intensity. What the hell, we're the Raiders. We've seen all types. “I didn't know what to make of them,” Long says. “I remember going into a bar in Santa Rosa, where we trained—the Bamboo Room it was called—and Ted Hendricks was sitting on a stool and next to him was this life-size blowup doll. He said, ‘Howie, meet Molly. Molly’s my date tonight.’”

The Raiders would use Long in pass-rush situations as a tackle in the nickel defense. He remembers the Patriots' John Hannah and the Chargers' Ed White taking him to school. Mike Webster of the Steelers put him on his back on the first play, and Doug Wilkerson of the Chargers “did tricks with me.” But the intensity was always there. And in the fourth quarter, when things started to sag a little, Long would come on strong. He got his sacks and he wound up leading the team as a rookie.

The Raiders acknowledged Long’s worth when they rewrote his contract after he staged a four-day holdout last July. They eventually gave him $3 million for four years, none of it deferred, a package that is the best in the NFL in terms of real money for a defensive lineman.

He started the last five games of the strike year, 1982, and by 1983 he was a regular. He began following Leggett around like a puppy. The players called him Howie Leggett. Lyle Alzado arrived from Cleveland with plenty of giddap left in his aging legs and a willingness to share 11 NFL seasons’ worth of knowledge with the young lineman. The club decided that Alzado should room with Long. “Lyle would bring a piece of chocolate cake and a glass of milk up to the room at 8:30, and at nine o'clock it was lights-out and the TV off,” Long says. “I thought, Oh my God, I'm back with my uncle Billy again. I'd get a roll-away cot and sneak over to Calvin Peterson and Marcus Allen's room and watch TV.

“In the huddle Alzado was our leader, no question about it,” Long says. “Still is. We say that Lyle will never retire. Eventually we'll prop him up on a horse and sew his eyelids open and he'll play forever. He'll be our El Cid....”

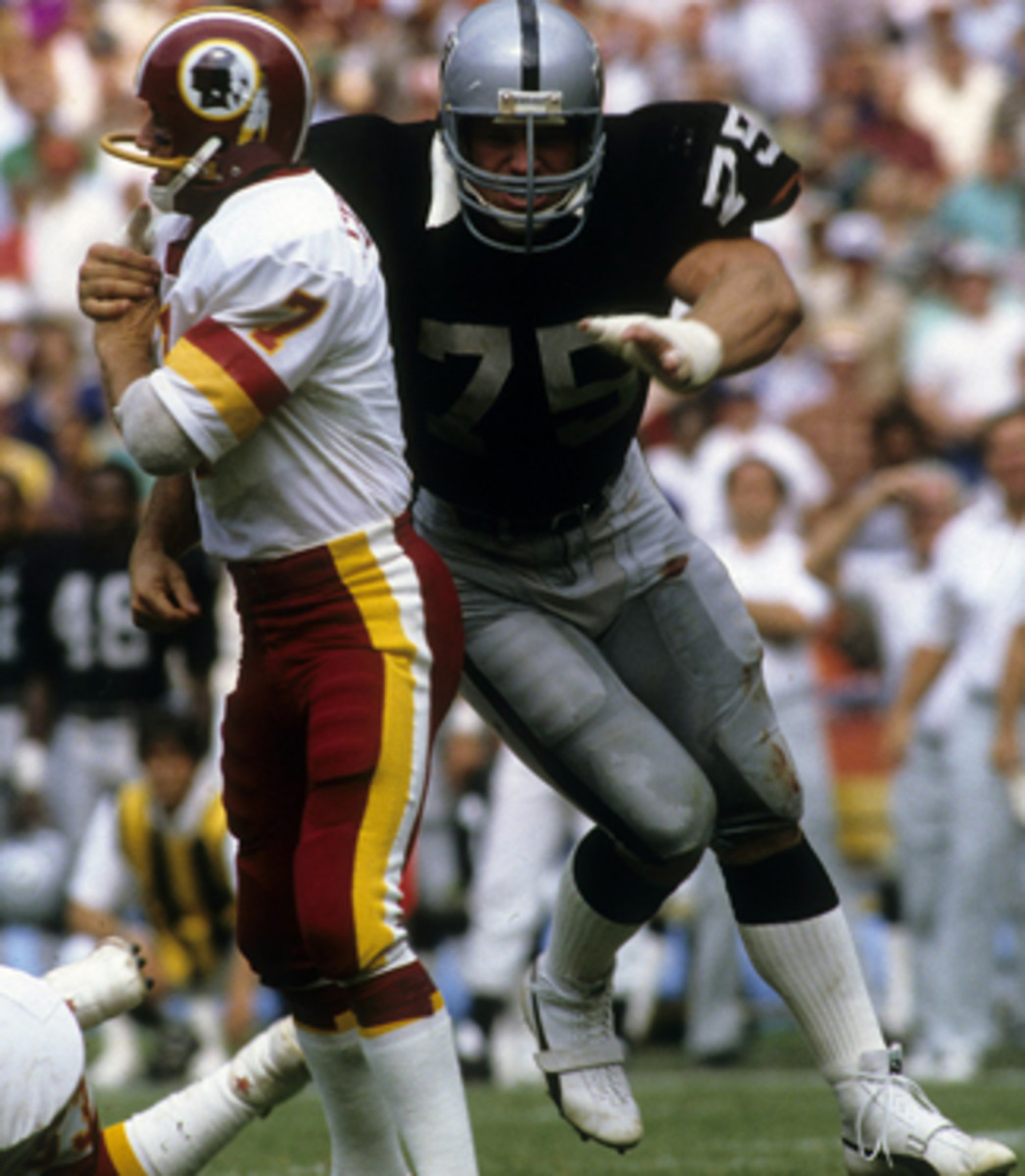

In his last two All-Pro years Long has become the Raiders' strongman on the defensive line, controlling the run and exerting pressure from the left end spot or as a tackle in the four-man pass rush. The night before a game he locks himself in his room with two cheeseburgers, a dozen iced teas and two reels of film. “If I don't look at films the night before, I feel naked the next day,” he says.

He has mastered lots of subtle tricks of the trade—for example: “One thing I learned is never bend over in the defensive huddle. Stay up high and watch the other team's sideline, especially if the quarterback is over there talking to the coach. There's always that moment when he leaves him and starts back to the huddle and then forgets something and goes back. If you watch their lips, that's when you might pick something off.”

Long's basic move off the line is devastating—it is the rip, an uppercut designed to break the opponent's grip and stop all forms of hand-to-hand combat. The hand fighters, he says, simply waste too much time. To counter Long's move, offenses use the tackle to set him up and then have the tight end crack down on his legs. That's where the trouble usually starts, setting off one of “the 80 or so fights I've had in the NFL,” which have earned Long a reputation as a wild man.

“A lot of teams do it, but Kansas City is the worst,” he says. “Willie Scott, their tight end, almost maimed me last year, and a big fight started. I told him. 'It might be legal, but do it again and I'll come down with my three-quarter-inch spikes and rip your ribs off.' That's the Catholic in me. Warn 'em first. Hey, look, I can't be responsible for what I do.”

A few mini-legends have already sprung up about Long. There was the time he went into the Seattle offensive huddle during a time-out and said to the trainer, “Give me that water. They don't need it. They're not doing anything.”

“A few guys in the huddle laughed, guys that I know,” Long says. “Ken Easley reminded me of it at the last Pro Bowl. He loved it.”

There was the time Long screamed at Chicago guard Kurt Becker: “I'm going to get you in the parking lot after the game and beat you up in front of your family!”

“Yeah, I said it,” Long says. “He'd spent the day flying over the pile and hitting defensive backs late. He was my target for the game, but I had missed him and sprained my back, so I was upset. Everyone has their favorite threat, and that's mine. Lyle's is ‘I'll kill you and everything you love.’”

The Raiders' reputation as intimidators took some lumps last year. Chicago outplayed them. Pittsburgh and Seattle ran the ball on them. Long sighs and admits, “Things were bad. Injuries, mistakes, some people just didn't play well.”

Three weeks before the end of the season Long was wondering if he would have a shot at the Pro Bowl. His sacks were down, thanks to the double-team attention he was getting, but the statistics didn't show holding penalties by opponents, and the Raiders figure that Long and the Bucs' Lee Roy Selmon led the league in that category.

“I won't have the sacks of a Mark Gastineau,” Long says, “and I won't get all those pursuit tackles. Our responsibilities are different. He's allowed to freelance all over the field. I have back-side responsibility. I have to play the reverses and cutbacks. Let me know when Gastineau decides to play the run.”

Al Davis, the Raiders' managing general partner, feels that Long is a player with “superstar qualities and room for improvement.” Long says he'll dedicate the 1985 season to zeroing in more accurately on quarterbacks. “I came in too high a lot of times,” he says. “They'd duck, and I'd miss.”

The Raiders acknowledged Long's worth when they rewrote his contract after he staged a four-day holdout last July. They eventually gave him $3 million for four years, none of it deferred, a package that is the best in the NFL in terms of real money for a defensive lineman.

It's always a shock when people meet Long for the first time. Last winter his uncle John, the ex-cop who's now the driver and bodyguard for the agent Bob Woolf, took Long to meet Woolf. They talked for a while and finally Woolf said, “You know I don't know how to say this, but you're...well, you're really not like I expected you to be...you're....”

“Civilized,” Long said.

“That's it,” said Woolf.

“It happens all the time,” Long said later. “I always spend the first five minutes convincing people I'm really Howie Long. They say, 'No, you're not. He's much meaner looking.' They figure I should be wearing a torn black jersey, going around raping and pillaging.”

The Boys and Girls Club of Boston sees a very private side of him. He has come back and spoken to the group twice. This fall he will treat 50 of the kids to tickets to the Raiders-Patriots game in Foxboro. “What I would have given if someone would have done that for me when I was a kid,” he says. It's a simple matter. You've gotten something from life, you give something back.

Long's fears and his self-doubts are almost gone now. But sometimes at night they do come back, and he feels that maybe this has just been a dream, that he'll wake up and he'll be back in Charlestown again. Then he begins to wonder what might have happened—if.... What if his grandmother hadn't been around? What if his uncle Billy hadn't taken him in? What if Dick Corbin hadn't taken him in hand? What if he had been accepted for the electrician's course at vocational school instead of being rejected?

“Well, he'd be an electrician right now,” says his aunt Aida. “A tall one. He wouldn't need a ladder.”

“I never would have made it out of Charlestown if not for all those people,” Long says. “I'd probably be working for the Boston Housing Authority, and I wouldn't be very happy. I wasn't a happy kid. But there was always someone there, always someone saving my ass—Ma, my uncle Billy, Dick Corbin and his wife and Earl Leggett.”

“Call it luck, call it circumstance,” Diane Long says, “but you have to wonder how many others there are like him out there, people who could have really done something if given a chance. They knew they were better than what they were, but they never knew what to do about it.”

Long stares out the window of his Redondo Beach home, at the lights winking along the Pacific Coast Highway.

“God gave me good people around me, and He gave me size,” he says. “It's kind of a miracle, really. Diane and I have talked about it. Where would I be now if God hadn't decided to rip me from stone?”

• Comments, thoughts or memories about Dr. Z? Send them to us at talkback@themmqb.com.