Best of Dr. Z: Sid Gillman, Screen Gem

This week The MMQB is celebrating the life and career of Paul Zimmerman, who earned the nickname Dr. Z for his groundbreaking analytical approach to the coverage of pro football. For more from Dr. Z Week, click here.

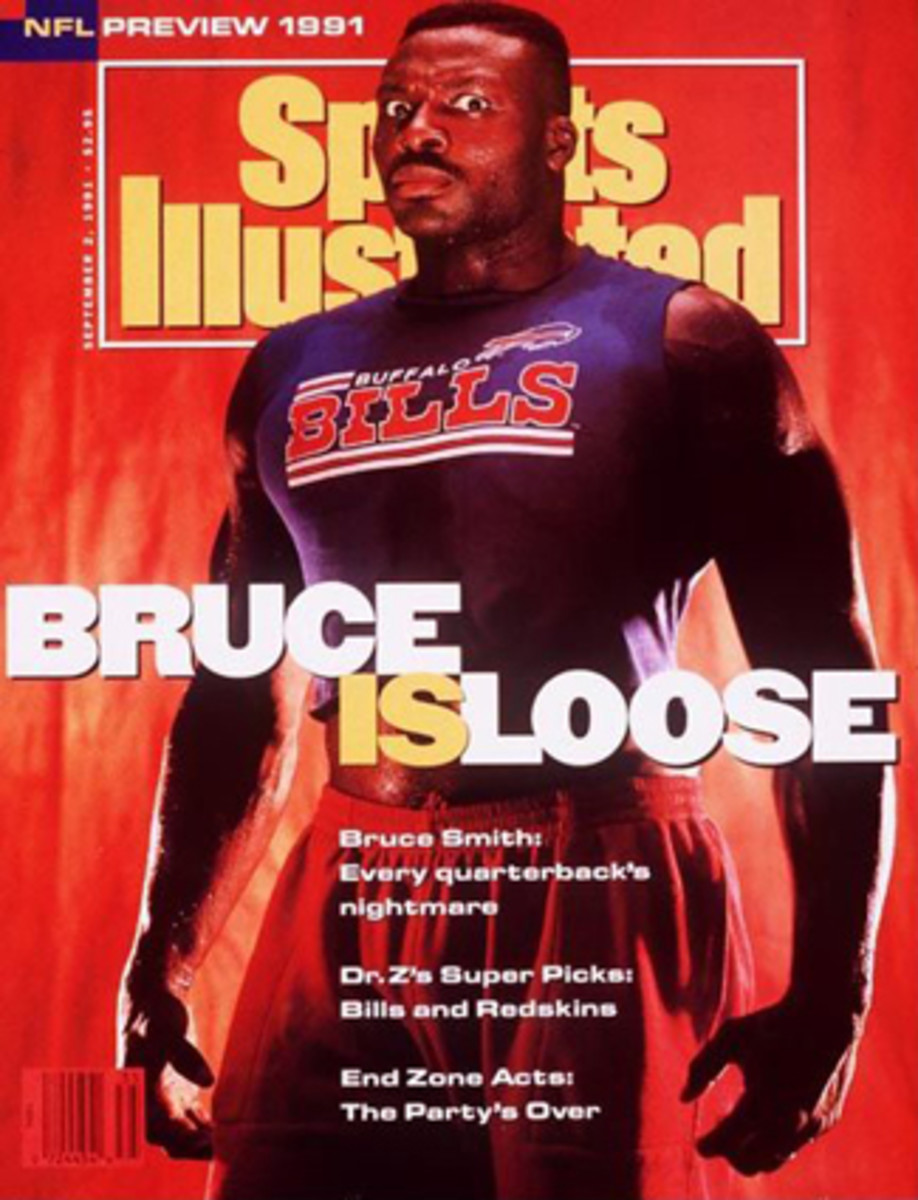

This story originally appeared in the Sept. 2, 1991, issue of Sports Illustrated.

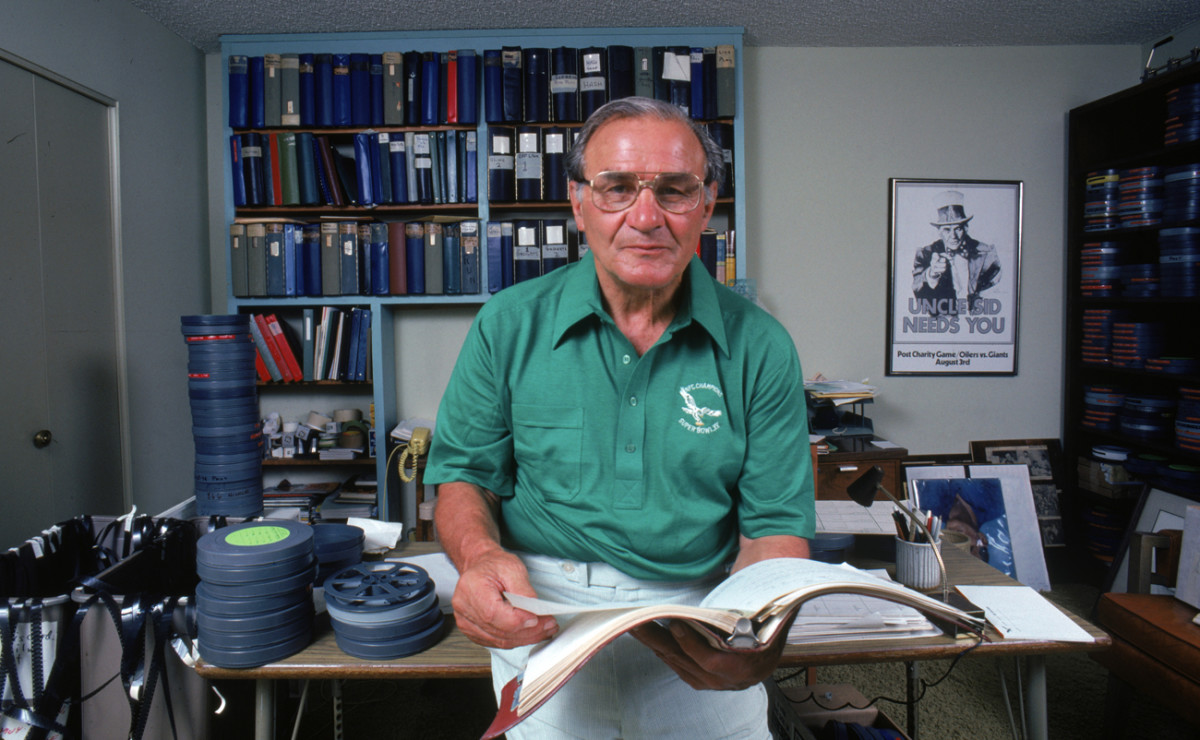

In the second-floor study of his house in La Costa, with the bright California sunshine fighting to pierce the carefully shaded windows, 79-year-old Sid Gillman is putting together history’s greatest study of offensive football.

There are maybe 500 cans of film in that room, gray cans for reels that show passing, blue for runs. Cut-ups, they’re called, identical patterns and maneuvers excerpted from miles of raw footage and painstakingly spliced together. Want to see the quick post? Well, pull up a chair and watch John Unitas to Raymond Berry or Bob Griese to Paul Warfield or John Hadl to Lance Alworth. Watch the finest passers and receivers who ever played the game run an hour of quick posts, or any other pattern.

There are individual game tapes on the shelves, stuff from the modern era, when tape took over for film as the coach’s best friend. Gillman, who set the tone for modern offensive football three decades ago, uses the tapes to evaluate the current crop of quarterbacks, to analyze the trends in the game, to break down each team’s offense. He saves what he likes, discards what he terms “ridiculous.” A couple hundred sheets of loose paper—diagrams, notes, ratings—represent his gleanings from those tapes. They will go into the 100 or so loose-leaf notebooks on another shelf, some of them containing 150 pages or more—50 years of offensive football.

Spend a few hours in that British Museum of football, breaking down tapes with Gillman, watching his pencil fly, trying to keep up with a mind that is constantly ahead of his fingers, a mind that is racing, always racing, racing ahead of all the people who came after him and tried to duplicate his system. Put yourself through an afternoon of that and you stagger out into the La Costa sun like a drunk, your brain reeling. Or maybe you’re met downstairs by Sid’s wife of 56 years, Esther, who has prepared coffee and sandwiches.

“Been watching football with Sid, huh?” she says, smiling.

“Have you ever done it?” you ask.

“Oh, sure,” she says. “I’ve done it for 56 years. I love it. Sometimes Sid will see something and he’ll yell, ‘Esther, come up here! I want you to look at this.’ ”

Occasionally, Gillman will shut off the projector or VCR, get up and open the shades and let the sun in, and stare outside and ask, “Why am I doing this? I’m almost 80 years old. Why am I evaluating these quarterbacks?” Then he’ll darken the room again and sit down and turn on the machine. “Well, why not?” he’ll say. “What else would I be doing? It’s my life, what keeps me going.”

They’ve tried to get him out of the game. Too crusty, too mean, too tough for the owners to handle, they’ve said. Yes, they’ve tried many times, and each time Gillman has drawn a deep breath and said, “Well, that’s it, it’s been a good career.” And then the phone would ring, and a week later there would be a story in the papers like “Sixty-one-year-old Sid Gillman has been hired....” Or 67-year-old Sid Gillman, or 76-year-old Sid Gillman.

He left San Diego late in 1971, after 12 years as coach and general manager of the Chargers, when he tried to challenge owner Gene Klein on the structure of the team. “Anytime a guy tries to put a gun to your head,” Klein said, “the results will be the same.” Said Sid: “I’ve got a big rear end. I’m going to spend the rest of my life sitting on it. I’m out of football and enjoying life.”

It was reported that he would be a commentator for a San Diego TV station, but a month later he was in Dallas, getting ready to go to work as Tom Landry’s quality-control coach. A year after that he was Houston’s executive vice-president and general manager, and he also took over as the Oilers’ coach five games into the 1973 season. In ’74 he was selected AFC Coach of the Year by UPI, after his Oilers went 7-7 and broke a streak of four losing seasons. The next season he went back to being the Oilers’ general manager, naming his defensive coach, Bum Phillips, as his replacement, only to be forced out three weeks later by owner Bud Adams—on a power play by Phillips. Bum didn’t want Gillman looking over his shoulder, and it was a bit of manipulation that had Sid vowing he was out of the game for good now. Honest.

Until 1977, when the phone call came from Chicago. The Bears, who hadn’t had a winning team for nine years, needed an offensive coordinator, and 65-year-old Sid Gillman was the man they wanted. He was on the next plane. Those Bears went to the playoffs for the first time in 14 seasons, and when they asked Walter Payton about Sid, he said, “I haven’t figured him out yet. I don’t know where he gets all his enthusiasm.”

One day someone approached Gillman to do some work for the Gray Panthers. “What is it?” he asked. A senior citizens’ group, he was told. “It’s not for me,” he said. “Hell, I live like I did when I was 35. I don’t believe in retirement groups because I don’t believe in retirement. How long can I keep coaching? How about forever? I’ll never walk off the field.”

But that’s exactly what he did after the ’77 season. He wanted to open up the offense. The Chicago brain trust wanted to keep it closed. “Younger coaches with old minds,” Gillman said, and he went back to La Costa and his film room.

The next phone call came from left-field. United States International University, formerly known as Cal Western, wanted to know if he was interested in coaching its team—USIU with 3,450 students on its San Diego campus, including 1,500 undergrads, about a third of them foreign; USIU with campuses in London, Nairobi and Mexico City. Sid Gillman working there would be like Henry Ford working at a local garage.

“My president told me to make the call,” says Al Palmiotto, USIU’s athletic director at the time. “I was practically laughing when I phoned Sid. I mean Sid Gillman, the father of modern offensive football. I said, ‘You wouldn’t by any chance be interested?’ and he said, ‘Sure, why not?’ ”

“What a lucky sonofabitch I am,” Gillman said afterward, “finding a place like this for the last years of my life.” It was December 1978. He was 67 years old. Four months later he was gone, having signed on with the Philadelphia Eagles to put in a passing attack for coach Dick Vermeil’s offense. But what he did in those four months at USIU became something of a West Coast legend.

Gillman was an innovator, one so creative and persuasive that a coach such as Bill Walsh, exposed to the Gillman system for only one year, in ’66 when he was a Raider assistant, could later say, “Much of what I did I got from Sid Gillman 20 years ago.”

Three of the coaches he hired—Tom Walsh, John Fox and Mike Solari—went on to coach in the NFL. A fourth one, Mike Sheppard, is now head coach at New Mexico. Two of the players he recruited, quarterback Bob Gagliano and cornerback Vernon Dean, became NFL starters. The ’79 USIU team, eventually coached by Walsh, went 8-3, tying the best record in school history.

“Sid put everything together in a month,” says Walsh, who now is an offensive assistant with the Los Angeles Raiders. “It was frantic. We were interviewing people in two offices at once. Running ’em in and out. Everyone wanted to come in and meet Sid. We got Gagliano on the rebound from Southwestern Louisiana. [He had left because he was homesick.] When we found him, he was reading gas meters for the city of Glendale.”

So Gillman worked for the Eagles in ’79 and ’80, the Super Bowl season. Vermeil flatly says, “We never would have made it to the Super Bowl if not for Sid Gillman. When we hired him, we hired an encyclopedia.”

And then Gillman retired. (“Physically and mentally drained,” Vermeil said.) “I’ve got to get home,” Gillman said. “I’ve got to spend time with my grandchildren.” And two years later Vermeil brought him back again, after the Eagles went from seventh in passing in the NFL to 20th. “I’m too young to retire,” said Gillman, who was 71 that season. “Once you’ve got football in your blood, you can’t get away from it.”

The motor never stopped. He signed on with the USFL in ’83 and ’84, first as the general manager of the Oklahoma Outlaws, then as a special assistant with the L.A. Express. He was back with the Eagles in ’85 as quarterback coach, then served as an unpaid consultant to University of Pittsburgh coach Mike Gottfried in ’87. The Panthers gave him the game ball after they upset Notre Dame 30-22 on the way to an 8-3 season.

“I don’t care if he’s going to be 80 or 90,” Gottfried, who is now an analyst for ESPN, said this spring. “If I’d gotten a head coaching job in the new World League, which I almost did, my first call would have been to Sid.”

Once in 1965, when Gillman was riding at his highest, with his Chargers on the way to their fifth AFL Western Conference title, Gillman addressed a booster club luncheon at the Hanalei on San Diego’s motel strip. Someone asked him about the money the players were making, always a sore point with Gillman and the players who had to deal with him. He drew himself up and you could see him stiffen, a tough, blocky-looking man in a sports coat and his perennial bow tie. He fixed his questioner with his well-known scowl and his answer was a snarl. “With some of them, football is a vocation,” he said. “With some, it’s an avocation. You know what football is to me? It’s blood.”

It was a rather alarming answer, but at the time no one in the audience realized that it could also be taken two ways: as 1) blood; and as 2) in the blood, deeply ingrained, never losing its visceral grip nor its intellectual fascination. Do it all, do it first and do it better, and if someone else is doing something you like, film it and clip it and splice it into your own reel and use it—only better.

The hard edges have softened now, his bitter, furious battles of the past have become subjects for anecdotes. The intellect remains, the total absorption in the pure beauty and geometry and science of what takes place on the field. Oh, you can still set him off. He’ll watch a game and he’ll notice a coach on the sideline and he’ll mutter, “Chairman of the Board.”

“There are two types of coaches,” he says, “the Innovator and the Chairman of the Board. The Chairman of the Board stands on the sidelines with his arms folded. He knows nothing about what’s going on, on the field. If the offensive coordinator left him, he wouldn’t know which way to turn. He doesn’t wear a headset. Without a headset a coach doesn’t know borscht. He’ll never make a decision, except maybe whether to go for it on fourth-and-one.

“The other guy, the Innovator, has a headset on and a chart in front of him. He’s constantly looking at his chart. He’s got everything calculated because he’s the guy who has put everything together. He calls everything.”

And Gillman was an innovator, one so creative and persuasive that a coach such as Bill Walsh, who was exposed to the Gillman system for only one year, in ’66 when he was a Raider assistant, could later say, “Much of what I did I got from Sid Gillman 20 years ago.”

And it’s all there, on the second floor of that house on Playa Road in La Costa, waiting to be tapped, to be shared by anyone so inclined. “A few years ago, when I was a free agent, I stayed with Sid in his house,” says Ron Jaworski, the former Eagles quarterback, who was the NFL’s Player of the Year, under Gillman’s tutelage, in 1980. “Before I knew it, he had me up in his film room, looking at film for three hours.”

“He told me a year ago,” Vermeil says, “that he was going to take a vacation during the football season and stop looking at films. I said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ ”

The alltime greatest? “Well, you have John Unitas, who’s in a class by himself,” Gillman says. “But I kind of had a thing about Joe Namath, kind of gave me goose bumps every time he went back to pass.”

It is late morning, the heart of Gillman’s time in the film room. In the early morning he walks the golf course at the La Costa country club, three and a half, maybe four miles. Afterward he eats breakfast at the clubhouse “with my boys, my buddies.” In the afternoon, it’s perhaps nine holes of golf, then a mile on the treadmill, then 10 laps of the pool. Two trips to the hospital—a hiatal hernia in 1969 and heart surgery almost a decade later—have turned him into a fitness buff. But the middle of the day is devoted to the film room.

On a table are nine letters. “Yesterday’s mail,” Gillman says. “Mostly requests for autographs.” One of the envelopes contains a dozen cards to be signed. Next to the letters is a playbook from a small-college coach. It is 62 pages long. “Could you please analyze this?” the attached note says.

“I’ll try, but ... you know,” Gillman shrugs. “I’ll tell him, ‘Great job, absolutely wonderful. You mind if I use some of that?’ No use discouraging a young coach.”

The phone rings. “You’re doing a what?” Gillman says. “A history of the American Football League?” (“Oh, god, another one,” he says under his breath.) “O.K., why don’t you call me at six tonight, if that’s convenient for you. I don’t know what you expect me to remember. That was 5,000 years ago.”

He is scowling now. “Everyone’s interested in the past, the good old days, the Golden Age, that’s what people call the ’40s and ’50s. God almighty, football’s so much better now, the techniques, the players. The game’s the greatest now. I’m part of the good old days, and they weren’t worth a damn. Who could play both ways now? I remember when I was with the Rams, I had a receiver tell me it used to be a feast against the Bears because he’d go against George Blanda playing cornerback. You think Lawrence Taylor could play both ways now, the way he chases quarterbacks? He’d be on his ass by halftime.”

He presses the button for the VCR. A 1990 New England Patriots game comes on. The Patriots? Why the Patriots?

“I want to see what every team is doing,” Gillman says. “I’ll get about 150 games a season. There are about five clubs that regularly send me their coaching tapes. Then I’ll have both VCRs working on the weekend, and I’ll get every game they show here. Plus, I want to see that young quarterback, Tommy Hodson. Dick Coury, their offensive coordinator, sent me a reel of five games. He wants me to evaluate Hodson.”

On the tape of the Patriots-Steelers game, Hodson takes a five-step drop, and throws a hook pass to Marv Cook, the tight end. The ball is dropped. “It’s a delay pattern and the receiver sat down early,” Gillman says. “It’s a coaching point. Why run into coverage? But watch the quarterback. See him bounce in place after he’s taken his drop? That’s what I always wanted my quarterbacks to do, to bounce. Now he moves up as he feels the rush, now he throws. Good technique. That’s what I’ve seen this kid do. I like him. I’m gonna tell Dick I think he can play.”

Quarterbacks have always been Gillman’s babies, his pride. They always commanded his special attention. Someone once asked him why. “Because when we have the ball, I want to see Gillman Jr. at quarterback,” he said.

“God, the things I learned from him,” Jaworski says. “If I could remember one tenth of what he taught me, I’d be a genius myself. It was like talking to the guy who invented football.

“Anything he told you, you know he’d been through a hundred, a thousand times. But as much as he was progressive, he was fundamental, too. You wanted to see a crossing pattern off a three-step drop? He’d put on one of his cut-up reels of all the great quarterbacks doing it. Something like the proper position of a quarterback’s hand under center? Well, he’d tape it and we’d spend hours watching it. The center-quarterback exchange? Mike Dougherty, our film man, would be lying on his back filming the exchange.”

Gillman has the current quarterbacks grouped into classes. There are his absolute blue-chippers, “guys who can sustain an offense for you”: John Elway, Joe Montana, Randall Cunningham, Warren Moon (“a beautiful passer; I don’t like the run-and-shoot, but with that guy running it, it’s so pretty to watch”), Jim Kelly and Dan Marino, who drives Sid nuts. “Totally undisciplined,” Gillman says of the Miami Dolphin passer, “but, my god, what a talent: what a quick drop, quick hands. But when he takes his drop, he’s all over the place.”

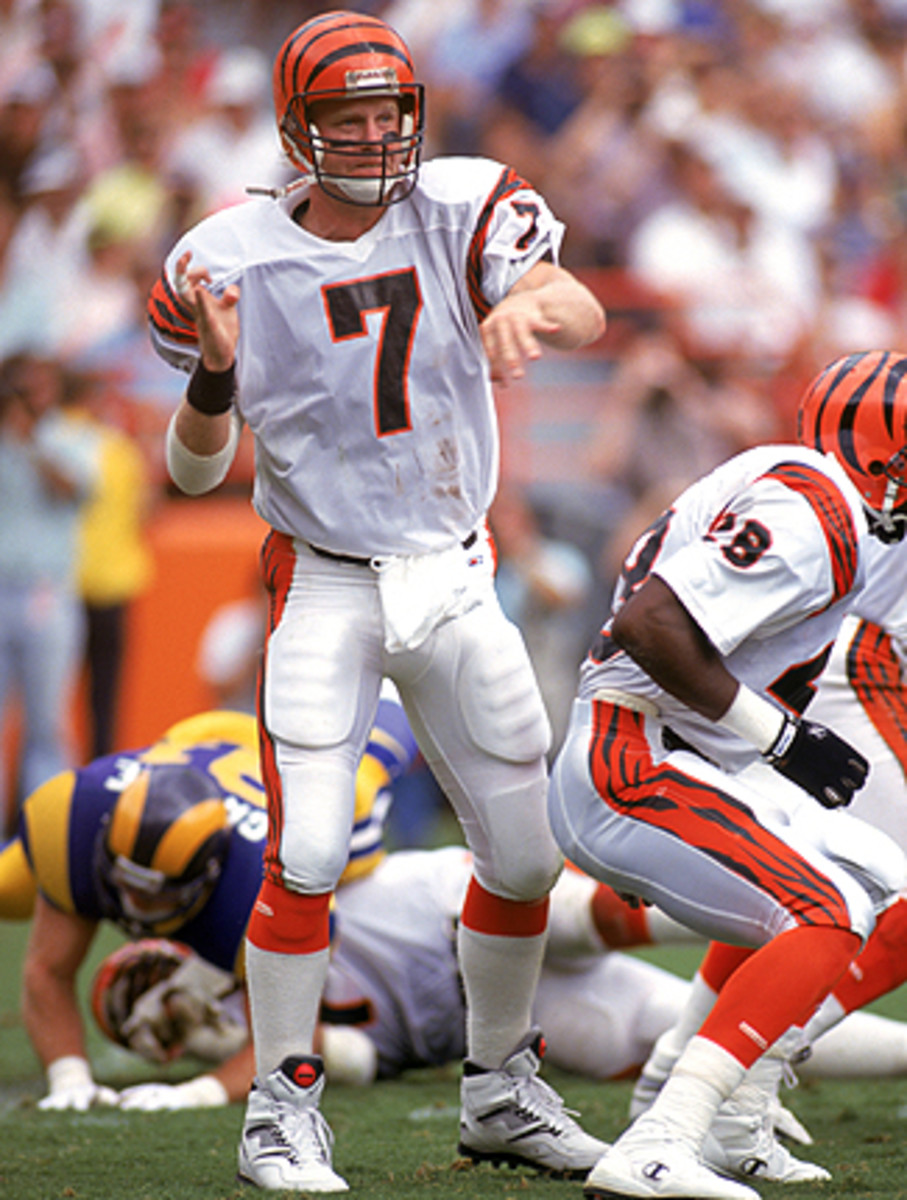

And then there’s his favorite, Boomer Esiason. “Technically the most perfect,” Gillman says. “He does all the things I tried to get my quarterbacks to do—bouncing in place to let the pattern develop, ball always held high. You see so many of them bring the ball down and around and all over. I just love watching the guy play.”

Gillman has a class that he calls tough old vets: Phil Simms, Steve DeBerg (“the courage that guy’s shown”). And a group of future stars: Timm Rosenbach, Troy Aikman, Steve Walsh, Jeff Hostetler, Jim Harbaugh, Steve Young (“Yeah, I know, he’s been around, but I still think he’ll be a Super Bowl quarterback someday”) and Jeff George, whom he rates a “super talent...great delivery, strong arm, good size, can move around and avoid the rush. But I question his accuracy on long balls, and then you have to ask, ‘Is he smart? Is he a leader?’ I don’t know yet.”

There are some quarterbacks he won’t evaluate until he sees more film, such as Don Majkowski and Chris Miller, and some who frankly puzzle him, such as Dave Krieg and Jim Everett, who he says “regressed completely” in 1990. And then there are a few who cause him to scowl. “Oh, hell, I don’t want to get into that,” he says. “You know who they are.”

The alltime greatest? “Well, you have John Unitas, who’s in a class by himself,” Gillman says. “You’re talking about alltime alltime, but”—and he pauses—”I kind of had a thing about Joe Namath, kind of gave me goose bumps every time he went back to pass.”

He puts another game tape into the VCR and starts the machine. It’s the Raiders, the one organization that has never snapped the cord with Gillman.

“Sid, geez, you’re talking about my father now,” says Al Davis, an end coach on Gillman’s first three Charger teams. In Davis’s office, ready to be wrapped and shipped, is a Sony TV—for Sid. The Raiders supply Gillman with tapes, invite him on trips, occasionally call for his opinion.

“He still thinks he’s coaching me,” Davis says. “He’s still dominating me. He doesn’t know I’ve grown up. He’ll say, ‘You can’t win that way,’ and I’ll say, ‘Hell, Sid, we’re winning.’

“All our terminology—and the terminology Bill Walsh took with him when he left here—came from Sid, plus a lot of the coaching points and much of the offense, at first. Sid’s idea was to spread the field and get everyone into the pattern. He liked the quick strike, the relentless attack down the field, same as Bill Walsh. The quick strike to Lance Alworth, where he breaks a short pass for 60 yards; the quick strike to Jerry Rice, same thing. But then we got away from that and started holding the ball longer, looking for the big one.

“I understand Sid’s mind. It’s a far-out mind, always looking ahead, always looking to incorporate new things. Anything he liked, he’d put it in. The smorgasbord approach. That’s where we eventually differed. I’d see one thing I liked, I’d stick with it. It’s like we’re both card players and he’s got to learn all the games—chemin de fer, pinochle, gin—and I’m a bridge player. I’d say, ‘Hell, let’s play bridge and win money.’

“But the real treasure I got from Sid was learning how to be a winner, what it took: commitment, love of football, excellence, work ethic. No one could ever outwork Sid. He taught me how an organization should be run. There are just so many intangibles that came from Sid, the foundation of how we practice, for instance. See it, write it, learn it, do it.”

Davis considers the late Paul Brown and Gillman the two forerunners of modern football: Brown more from an organizational standpoint; Gillman for organization and offensive concepts. “Every major-college pass offense, and a lot of those in the NFL, stem from the Gillman system,” he says.

And what is that system? Gillman says it was born in the early 1930s when he was an All-Big Ten end at Ohio State, and then an assistant to Buckeye coach Francis Schmidt (Close the Gates of Mercy Schmidt), who in turn was influenced by the wide-open football of the Southwest Conference. It developed in Gillman’s years as an assistant at Ohio State, Denison and Miami of Ohio from 1934 to ‘43, then as Miami’s head coach from 1944 to ‘47. From Army’s Red Blaik, for whom he worked as a line coach in ‘48, Gillman learned situational substitution—platoon football, they called it. Gillman taught his linemen option blocking—take the man wherever he was going—with the backs breaking off that block in either direction.

A young coach from St. Cecilia’s High in Englewood, N.J., Vince Lombardi, often visited West Point in those days. For hours he and Gillman talked football, and it was Sid’s strong recommendation that got Lombardi hired as his successor in 1949. The footprints of Gillman’s option-blocking schemes were all apparent in Lombardi’s game plans for the Green Bay Packers a decade later. Run to daylight, they called it.

And then there was the film study. Lord, how Gillman loves those films, going back to the days when his father ran a chain of movie theaters in Minneapolis and Sid would get the projectionists to clip football bits for him out of the old Fox Movietone newsreels. “The West Point players had credited him [Gillman] with introducing practice films and game grades at the Military Academy, and Vince brought those ideas to the Green Bay Packers,” Jerry Kramer wrote in his 1968 book about the Packers, Instant Replay.

As the head coach at Cincinnati from 1949 to ‘54, Gillman exploited situational substitution. He came up with a name for his defensive unit, the Chinese Bandits, and a young assistant named Paul Dietzel took the name with him to LSU and made it famous.

Gillman’s five years with the L.A. Rams (1955-59) were the launching pad for his concept of the attacking game, and then when he went to the Chargers in 1960, it all came together. Spread the field, put your wideouts at the extremities to force the defense to cover more ground (to open up holes), fill all five passing lanes, preread the defense and hit the receiver on the break. “When the passer’s back foot hit the ground on his setup,” Gillman says, “I wanted the ball gone. If no one was open, if he had to buy time, I wanted him to bounce in place. And then I only wanted him scrambling as a last resort. When you bounce, you maintain your balance. When you start moving, you create an unnatural position for yourself. I want everything to be natural.”

His running plays were quick thrusts, his linemen fast and agile, able to pull and lead sweeps. Ron Mix, nine times an All-AFL choice, was one of history’s great pulling tackles. The Chargers were always looking for ways to beat people around the corner.

Gillman devised his own terminology and teaching aids—the 11 coaching points of the aerial game, the five offensive passing lanes. Every route bore a single-digit number, and he would simplify the play-calling to three numbers. For instance, his favorite pattern, an 848, would be the X receiver, or split end, running an 8: a 22-yard post; the Y receiver, the tight end, running a 4: or a 12-yard turn-in; and the Z man, or flanker, mirroring the same 22-yard post (an 8) on the other side.

In 1962 he took a heavy-legged, triple-threat back from Kansas, John Hadl, whom Detroit had drafted as a runner, and developed him into one of the game’s great touch passers. He turned Lance Alworth, a flashy halfback from Arkansas, into the deep thrust of his attack, a wideout who pierced the AFL’s zone defenses like an arrow.

His cut-up reels were for individual study (“There’s not a thing that happens on the field that I don’t have a reel for,” he says), and the point of the whole system was to simplify. “Why complicate things?” Gillman says. “If it’s an up, call it an up, not something exotic.”

The Gillman system spread like branches of a tree throughout the world of football. His assistants on those early Chargers, Chuck Noll and Jack Faulkner, took it to Pittsburgh and Denver, respectively, then Faulkner took it to the Rams as their special assistant coach. Al Davis and Al LoCasale took it to Oakland, where it rubbed off on Walsh. Kay Stephenson, Dan Henning and Don Breaux all had been quarterbacks for Gillman at San Diego, and his ideas followed them to Buffalo and Atlanta and San Diego and Washington. As head coach at Miami of Ohio and Cincinnati, Gillman had groomed such future coaches as Bo Schembechler, Dietzel, Bill Arnsparger, Johnny Pont and Ara Parseghian. And then there was the Florida State connection.

Bill Peterson, who became the Seminoles’ coach in 1960, was outmanned in talent and faced with a schedule loaded with SEC heavies. He knew he had to learn the passing game to survive. He attended every Charger camp, learning a system that became his own system at FSU. Occasionally he would bump into an eager young line coach from San Diego State named Joe Gibbs.

“The Chargers’ practice field was a favorite place for young coaches to run up to,” Gibbs says. “I’d follow their line coach, Joe Madro, around wherever he went. They’d share everything with you. The techniques were what I wanted to copy. I’d think, Hey, man, those guys are great!”

Breaux’s contact with Peterson at the San Diego camp earned him a place on the FSU staff in 1966. When Breaux left a year later, he recommended Henning to replace him. When a vacancy opened up for an offensive line coach, Breaux called Sid to recommend someone who knew the drop-back passing game. He came up with Gibbs, who was hired in 1967. The Seminoles ran the San Diego offense, and the roster of assistants who worked in that FSU program reads like a who’s who of football coaching: Henning, Breaux, Gibbs, Don James (University of Washington), Bill Parcells (Giants), Ken Meyer (Jets, 49ers, Seahawks) and of course Bobby Bowden, whose Florida State offense these days bears a striking resemblance to the old Sid Gillman operation.

In his darkened room in the house on Playa Road, Gillman still grades and analyzes and breaks down the tapes, occasionally putting up an old cut-up reel of film “to refresh myself.”

“If there’s anything new in the game,” he says, “I want to know about it.” Is there still room in the game for a man who will be 80 in October? Is there someone out there who would like his offense coordinated?

“Oh, yeah, sure, they’re all rushing to hire an 80-year-old coordinator,” Gillman says. “Quality control? I’ll tell you something about quality control. It’s only as good as your quarterback. If he goes down, you can take your quality control and shove it.”

“Sure, there’s a place for Sid,” Davis says, “but it’s as a teacher. He should write more, do his own tapes, teach his system to high schools and colleges. He should have an academy, a minority coaching program, maybe.”

Gillman’s oldest coaching colleague, Madro, who played for him in the late ‘30s and coached for him right through his Houston days, still keeps track of Sid but doesn’t call him too often.

“What are we gonna do, reminisce about old times?” Madro says. “He doesn’t want to and neither do I. All that film stuff at his age. He’s gonna go blind. Of course I said that 10 years ago.”

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.