Gino Marchetti beloved by Baltimore for his Colts and fast food careers

It’s still hardto argue with that closed-loop burger-joint jingle, the one that could be heard up and down the East Coast throughout the ’60s and ’70s: Everybody goes to Gino’s, ’cause Gino’s is the place to go. Even if not much of anybody goes to Gino Marchetti’s anymore, unless you count the foxes that appear from time to time in the rough beyond the plate glass of the living room of the Marchetti home outside of Philadelphia.

Oh, his children come by; and his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. It’s easy to get time with Nonno and his wife of 38 years, Joan, with five kids living no farther than the Poconos, two hours away. Three generations help certify the distance this patriarch must reach back to find a time when a football player didn’t feel the need to perform a mazurka to celebrate simply doing his job, when his Colts could still be found in Baltimore, the city to which they first belonged. “It’s just a shame what the NFL did,” says old number 89, who since Jan. 2 has been living past his uniform number. “They could have at least let Baltimore keep the [Colts] name.”

Marchetti is still tethered to the Charm City; he has no affection for—even finds himself rooting against—that team in Indianapolis, which relocated in 1984 and then promptly unretired his number to give it to some random tight end before an uproar finally overturned the decision. Of the original Colts and their original home, he nails it six ways from Sunday: “We were like the great high school team in a small town.”

• SI’s Where Are They Now issue: This year’s stories, all in one place

Next to the hunched heroics of fellow Baltimore co-captain Johnny Unitas, Marchetti’s performance at defensive end had a more vertebrate, workaday quality. He played in 121 straight games (all for Baltimore) between his arrival in 1953 and his final appearance, in ’66, and he was named a Pro Bowler 11 times in a row. He famously looked forward to training camp, where once, at age 35, he ran the 40 in five seconds flat. At his spot on the left flank of the Colts’ line he hammered out the template for the modern end, that blend of size, quickness and agility that would be embodied in Deacon Jones and then Reggie White and then J.J. Watt, the player who can dart laterally to catch a ballcarrier and sprint forward to collect the sacks that today lend the position its glamour. At weigh-ins he would slip lead into his jockstrap because coaches back then believed a lineman should be heavy; Marchetti, who rarely played above 240, knew better. In his day the NFL hadn’t yet enshrined the sack as a statistic, but Baltimore’s staff, going through game film at the end of one season, credited him with 43.

For a man so identified with his sport, Marchetti bracketed that career with two consummate male experiences apart from football. Before the NFL, before playing on a legendary team at the University of San Francisco, he served in World War II, an 18-year-old infantryman in the Fighting 69th, lugging a machine gun along the Siegfried Line into the Battle of the Bulge. “The first time I saw snow, I slept in it,” he says. Then, after retirement, he built up and sold the hamburger chain that made him a wealthy man.

Today, still able to summon most of the 6' 4" inches at which he played, the old Colt stands as a witness, his speech a little slowed but his memory as stark and durable as the white marble of a row house stoop. He’s the guy who, when he learned in 1962 of Carroll Rosenbloom’s plans to make a coaching change, urged the Colts’ owner to hire a Lions assistant and former teammate named Don Shula. Marchetti was in Hershey, Pa., the night Wilt scored 100, there to take part in an undercard exhibition that was a Colts-Eagles basketball game—though by the time Chamberlain set the record, Marchetti and his teammates had long since drifted off to hoist beers in some veterans’ hall. In the locker room one day he heard someone wonder aloud when injured first-stringer George Shaw might be back and articulated what others had only just begun to sense: “It doesn’t matter. Unitas is the quarterback now.”

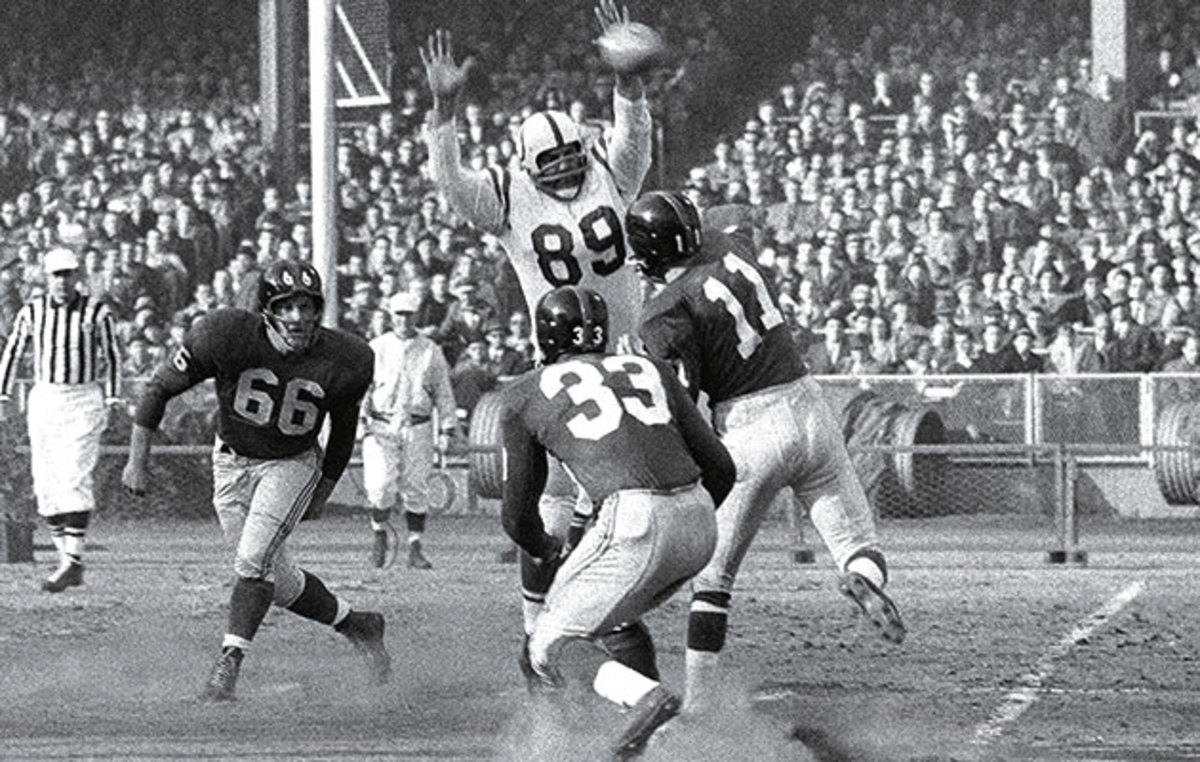

In fact, Marchetti was as much notary as witness—the man whom NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle (USF’s publicist during Marchetti’s time with the Dons) would recommend to anyone who wanted to know what players were thinking. Oddly, something that the public remembers well stands as a rare feat that Marchetti failed to see out: overtime of the 1958 NFL Championship Game between the Colts and the Giants. With three minutes to play in the fourth quarter, facing third-and-four from its own 40, New York had a chance to run out the clock on a 17–14 lead. The Giants called a sweep around right end for Frank Gifford, who chose to cut back over tackle, if only to avoid Marchetti. Shedding a block, Marchetti lunged back at Gifford and struck him waist-high. Marchetti wound up beneath Gifford, at which point his bookend on the Colts’ line, Eugene (Big Daddy) Lipscomb, threw another 284 pounds on top of the pile. The impact broke two bones above Marchetti’s right ankle.

In the annals of taking one for the team, few people would absorb so much in the service of so worthwhile a result. The linesman spotted the ball one foot short of a first down, forcing the Giants to punt. And while Gifford has insisted over the years that he picked up that conversion—that Marchetti’s screams of pain distracted the official into an errant placement—a 2008 ESPN documentary, using forensic mapping techniques on old film, determined the Colts did indeed stop Gifford short, by nine inches.

It took six men to stretcher Marchetti off the turf. His litter-bearers wanted to take him to the locker room, but he ordered them to set him down behind the end zone. Picked up and put down every few plays, his leg wrapped in ice, Marchetti watched as Unitas led a drive for the field goal that forced the first sudden-death period in NFL history.

By the second series of what would be eight-plus extra minutes, Marchetti finally agreed to be taken from the field, capitulating to fears that he could get trampled by the crowd and that the plunging temperatures would send his body into shock. Not until the first teammate burst through the doors of the locker room did Marchetti, stomach-up on a training table, learn that fullback Alan Ameche had scored in the gloaming to win for the Colts the game that launched the NFL into the modern, Madison Avenue–driven age.

• From the Vault (1959): The Best Football Game Ever Played

Marchetti has followed the NFL’s evolution since then and understands the changes, even if he doesn’t endorse every one. “They want to keep the QB healthy, no matter the cost to the defensive player,” he says. He pities today’s D-linemen, who he thinks aren’t likely to get the benefit of a referee’s doubt. “You’re going full-speed, and a 300-pound tackle is knocking you around,” says Marchetti, who claims to have never been assessed a 15-yard penalty during his career, “but people come to see the quarterback, and if the quarterback goes, the draw isn’t there.”

In the aftermath of the 1958 title game, surgeons operated twice to repair Marchetti’s leg, and the injury had no bearing on the rest of his career. But it turns out that doctors missed a bone fragment. It migrated down as far as it could and, over the years, ground away to form a callus on the ball of his foot. “Every step I took, the thicker it’d get,” he says. “And being in charge of all those restaurants—I really worked it.”

Only within the last year did he submit to one more operation, which has brought some relief. A moment for the Colts, a moment for the NFL, delivered a chronic reminder for most of the rest of Gino Marchetti’s life.

Poverty chasedErnest and Maria Marchetti from the hills of Tuscany to those outside of Charleston, W.Va., where Gino’s father worked in the coal mines through the Depression. When Gino was young, the family left for Antioch, Calif., an industrial town east of San Francisco, where Ernest opened the Nevada Club, a place to find food and drink and legal backroom poker.

Ernest had become a U.S. citizen, but with the outbreak of World War II it suddenly mattered that Maria hadn’t. Never mind that her eldest son, Lino, served in the U.S. Army and that Gino would soon enlist as part of a deal with an antagonistic teacher that allowed him to collect a high school diploma. With Maria exiled from Antioch for fear that she might commit sabotage or espionage on behalf of Mussolini, the family relocated to an apartment just outside of town. “Did they think she’d blow up the fiberboard plant or something?” her son posits now. “Every day we’d come home and she’d be crying, saying things like, ‘Look how I’ve made you live.’ ”

After the war Gino spent one season at Modesto Junior College, then returned to Antioch, where he worked the counter at Lino’s bar. Gino wore a leather jacket, his hair long and tucked behind the ears, with a motorcycle to boot. But football had wormed its way into his blood, so he and a buddy organized a semipro team, the Antioch Hornets. When a recruiter from USF walked into Lino’s bar and asked where he could find Gino Marchetti, Gino said, “That’s me,” and quickly snubbed out his cigarette.

The Dons who went 9–0 in 1951 included eight players who would go on to the NFL, two of them African-Americans—Ollie Matson and Burl Toler. In a team meeting at the end of that season, Marchetti and another white player, Bob St. Clair, presided over the unanimous decision to reject a bid from the Orange Bowl that was contingent on USF’s leaving its black players home. In the team photo of those Dons—the Undefeated, Untied and Uninvited, as they were proverbially known—Marchetti sits beaming at the center, a human bonding agent, with Matson (who was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame on the same day as Marchetti, in ’72) to one side and Toler (later the NFL’s first black referee) to the other. After one game, while out with Toler and a couple of white teammates, Marchetti fumed at a bar owner who turned them away. “Right there, I told Burl how my mother had been kicked out of town,” Marchetti explained to Unitas biographer Tom Callahan. “For a minute, I considered roughing up that bar.”

Like all NFL players of his era, Marchetti had to work during the off-season. At first he’d drift back to Antioch, herding cattle or tending bar for Lino; later he’d stick around Baltimore, setting duckpins at a bowling alley (“two cents a line”) or working in the iron mill out on Sparrows Point (“buttholing”—shinnying along beams in a straddle position). Like any “Bawlmer Merlin” workingman, at quitting time he’d repair to a tavern for a Natty Boh. All of which enriched his understanding of how, with a second NFL title in 1959, the Colts obliterated the inferiority complex of “Smalltimore,” the city that hadn’t won anything of relevance since the Orioles of Wee Willie Keeler, back in another century. “They loved us to death,” Marchetti says. “And we loved them back.”

• Where Are They Now: Refrigerator Perry mired in a stubborn spiral

Rosenbloom knew this, and several weeks before the 1958 title game he summoned Marchetti. You have a name and a following, the owner told him. It made sense to live in Baltimore year-round and go into business. And Rosenbloom wanted to help.

The following April, Ameche-Gino Foods Inc., opened its first Gino’s restaurant, staked in part by a portion of Marchetti’s $4,674 championship share. Marchetti’s teammate already operated Ameche’s Drive-Ins, with a menu featuring a 55-cent Ameche’s Powerhouse hamburger. Aware of a booming chain out west called McDonald’s, Ameche wanted to introduce 15-cent burgers, but he needed another name to avoid undercutting the pricier Powerhouse. Gino’s provided a fresh brand for a trending concept.

True to his word, Rosenbloom vouched for a 10-year, $100,000 lease at an early Gino’s location that wound up generating $15,000 a week and ignited the business. Marchetti felt so indebted that he twice came out of retirement at Rosenbloom’s request. By the time he left the Colts for good, in 1966, Gino’s counted 65 outlets, making it the largest chain of company-owned-and-operated restaurants in the East. The ride lasted into the late ’70s, when the company suffered from overambitious expansion in a soft economy.

At the time of its sale to Marriott International, in 1982, Gino’s owned 313 restaurants. Marriott converted 180 of them to Roy Rogers stores; the rest were closed or sold off, most to Kentucky Fried Chicken. But enough of the $48 million price tag wound up in Marchetti’s pocket for him to live the good life. In the summer he deep-sea fished off Cape May from his 38-footer, the Miss Gina, named for his oldest daughter, then sailed it down to Florida for the winter. He bought a Harley-Davidson, then sold it after Pennsylvania passed a mandatory helmet law. (For years he’d worn a helmet as part of making a living; the old hard guy whose hair once trailed in the California breeze wasn’t going to do so on his own time.) He dabbled in raising and racing horses, a throwback to his days riding in the Contra Costa County sheriff’s posse. And he kept a hand in the hospitality business with a fine-dining restaurant on Philadelphia’s Main Line.

At one point Marchetti ballooned to 330 pounds—“I ate and drank my way through the state of Pennsylvania,” he says—and in 1981 he needed three stents to be inserted following a heart attack. But a regimen of walking helped him drop 85 pounds, and he has kept most of the weight off. “The dog,” he says, nodding at Cinder, a poodle-schnauzer mix, “I’ve got to walk him.”

He has slaked his competitiveness in fishing tournaments and bowling leagues, where in 2005 he finished one final-frame 5-pin short of a perfect game. And in 1978 he helped the Colts beat the Giants once more, in a made-for-TV touch football reunion in Central Park.

He still has his stories and the lucidity to do them justice. Details are pegs on which to hang each tale: the red Chevy, parked outside the Marchetti family home, that enticed Gino and his younger brother, Angelo, to fatefully meet a visiting coach from Modesto, who really wanted Angelo but hey-what-the-hell told Gino to come along to campus too. The 1958 championship-game ball, wrested from a cop by center Buzz Nutter and awarded to Gino, who protested, “But I didn’t even finish the game.” The bottle of bourbon, hidden beneath the coat of Clark Gable, whom the Colts once ran into at the Los Angeles airport while out to play the Rams; a photo, now hanging in the Marchettis’ den, was taken moments before the Hollywood star dropped that bottle, shattering it on the floor.

Of the five Colts posing with Gable—Marchetti, Unitas, Ameche, Bill Pellington and Carl Taseff—everyone but Marchetti is now dead. “My wife tells me, ‘Gino, you were blessed,’ ” he says. “Even going into the Army, the G.I. Bill sent me to Modesto. Modesto didn’t really want me, yet I was the one who wound up staying, not my brother. After that, USF. And then Carroll, begging me to move to Baltimore. . . .

“Those things all just happened. I could say I planned it, but I didn’t. I was just a dumb guy standing there saying yes.”

It’s hardto imagine a patch of Maryland that makes more sense as the staging ground for a Gino’s-brand comeback than the town of Glen Burnie. Much of the housing stock, built for veterans returning from World War II, has remained in families for generations. No fewer than four bowling alleys still operate within a 15-mile radius. And the Gino’s Burgers and Chicken now on Ritchie Highway occupies the sceptered spot where an original Gino’s once stood—the very outlet where Marchetti used to swing by and pick up chicken before heading out for a day on Chesapeake Bay. “When we were building here, people driving by would honk their horns and yell, ‘You better have the Gino’s Giant!’ ” says Karen Foreman, the franchisee who opened the restaurant in September 2012, referring to Marchetti’s version of the Big Mac. “It’s so emotional for people. Not a day goes by without somebody telling me their Gino’s story.”

When Rosenbloom’s successor, Robert Irsay, took his team away in the middle of a snowy night in 1984, it hurt in the way that it hurts when a scab is ripped off—but the next morning the team was gone, and at least the healing could begin. But Gino’s left torturously over a decade, from the company’s sale in ’82 to the shuttering of the last outlet, in Pasadena, Md., in ’91. Many Marylanders conflate the team of their youth with the food they grew up on, and the departure of Gino’s compounded the pain. Says Tom Romano, an executive with the original Gino’s who has brought the brand back to life (here and in Towson, Md., so far): “When Gino shows up at a Gino’s, it feels like mom’s making you soup.”

On this hazy Saturday in May at the Glen Burnie Gino’s, the Great Eponym himself is on site. People start lining up at noon for a 2 p.m. meet-and-greet. Marchetti devours a Gino’s Giant, then takes a seat under a tent, where fans offer thanks—“for when it was a game, not a business” . . . “for your [military] service” . . . “for the memories.” One fan has even lugged in a cinder block from an original Gino’s building, with the distinct red-blue-and-white tiles intact on one face. Marchetti signs it.

For nearly three hours they come uninterrupted, never fewer than 50 in line at a time. Marchetti signs a seat back salvaged from the Colts’ old home, Memorial Stadium. He signs an envelope adorned with a stamp commemorating the Battle of the Bulge. He signs Gino’s ashtrays and Gino’s stock certificates and an old 45 rpm record pressed with Chuck Thompson’s radio call of what would come to be known as the Game That Made the Game. He signs booster badges commemorating the day he retired—they were sold, at 50 cents a pop, to surprise Marchetti by flying his dad to Baltimore, where Ernest had never before seen Gino play the sport that Ernest never wanted his son to play because he rightly feared that Gino would get hurt. Gino signs creased black-and-whites of himself posing with fans, pictures brought by the very people in the frame, 10 or 20 years his junior, now into their 80s and 70s. Adorers and hero alike congratulate one another on how well they’ve held up.

Greater Baltimore has emptied its attic and laid the contents at the feet of a man who treasures every artifact as much as its owner does. “They never talk to me about the Ravens, I’ll tell you that,” he says.

When only a few lingerers remain, Marchetti pulls his head up and beams, and he begins to croak out that old tautological tune: “Everybody goes to Gino’s”—and here people join in—“ ’cause Gino’s is the place to go.”

Then, to no one in particular; smile even broader; now witness, notary and bailiff; big guy to the end: “You better go, or you’ll get the hell kicked out of you!”