Pity The Kicker

By Dylan Howlett

Read Part II, “A Lonely World”, and Part III, “Makes and Misses, The End and The Aftermath.”

Here is a picture, and its thousand words.

Nate Kaeding, Chargers placekicker, stands on the sidelines after missing his third of three errant field goal attempts during a playoff game. His helmet is on, his eyes are glazed, his mouth is half-agape. CBS flashes a graphic beneath Kaeding’s catatonic stare, because misery needs context. Missed field goals, regular season: 3. Today: 3. A yellow highlighter denotes today’s three as a “career-high.”

The specter that has always tormented him is now too real. It leeched into him when he pulled his Toyota Camry into the players’ lot that afternoon, just as it did before every game: The only way I’m going to be happy today is if I don’t miss a kick. It’s a thought that haunts no other player, he is sure, save the opposing kicker.

His right leg had betrayed him, just as he had always feared. The Chargers would lose to the Jets, 17-14, a margin underlined by his three misses, and their 13-win regular season was for naught. During that 2009 regular season, Kaeding tied for the NFL lead in made field goals (32) and was one of four kickers to make more than 90 percent of his attempts (91.4). That, too, was forgotten. The specter was now a tangible horror. He doesn’t know now that he’ll never attempt another kick in the NFL playoffs, that there is no atonement waiting for him on another Sunday. This is it: a career high, and a life low.

He is shattered. And so he will remain, the picture says, because how could he not? He’ll always graze the shards of his personal failure. It is forever, as is this picture, a man peering into his new destiny of nothingness. Pity the living, we must. Pity the kicker, we must. Yet we do not.

There was anger—the type of numb rage that has no time for sympathy—the night of January 17, 2010. There was a fan at a nearby Wal-Mart shown on the local news. He wanted a refund for his No. 10 Chargers jersey. Kaeding saw the report live.

There was the Facebook group, “Nate Kaeding needs to be fired.”

Nate Kaeding, I HOPE YOU READ THIS YOU F------ FA----! YOU ARE A DISGRACE TO THE CITY OF SAN DIEGO, THE SAN DIEGO CHARGERS FRANCHISE, AND THE GAME OF PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL!

KAEDING’S ASS BETTER BE F------ GONE BEFORE THE WEEK’S OUT. IF THAT SON OF A BITCH IS STILL ON THE CHARGERS ROSTER EVEN NEXT PRESEASON THE FANS BETTER TEAR DOWN THE STADIUM IN PROTEST.

There was Twitter, and the suicide barbs.

Heard that Chargers kicker Nate Kaeding tried to shoot himself, but all his bullets ended up either short or wide left.

Did you hear Nate Kaeding tried to slit his wrists with piano wire? He couldn’t get his hands inside the uprights.

There was his vandalized Wikipedia page.

Nate Kaeding is a total f------ fa---- b---- and I hope he dies in his sleep tonight.

“You give up on people feeling sorry for you as a kicker a long, long time ago,” Kaeding says. Maybe because it had happened before, against the Jets, in the playoffs, at San Diego’s Qualcomm Stadium in 2005: A rookie from Iowa, Kaeding missed a game-winning kick in overtime, and the Chargers lost. Maybe because Kaeding, the sixth-most accurate kicker in NFL history, made only eight of his 15 career playoff kicks. A Chargers fan on reddit reduced Kaeding’s last name to a backhanded acronym: Kicks Ass Except During Important NFL Games.

The full picture. It is Kaeding’s face on the Qualcomm sidelines, his somber look embalmed forever. The picture wants to mourn. What a sad existence, the life of a kicker, always flailing and gasping and motioning for the Heimlich.

But the picture deceives.

“I always like to look at it like—actions on the field and even life in general—you are kind of writing the story,” Kaeding says. “When a chapter or a page gets written that you didn’t intend to have written, that wasn’t part of the plan, it takes you a while to own that story, you know? But you have no choice. Your story’s your story.

“My hope,” Kaeding says, “is that on the third or fourth chapter, my whole professional career, good, bad or indifferent, is just that: It’s just a chapter.”

The picture, then, requires more than a thousand words.

* * *

The primordial ritual of blaming the kicker has no definitive genesis, though it has been around, it would seem, forever. Its uncertain origins might rest in the exasperation of a football coach in Cleveland, a place that is keen on saviors and well-versed in disbelief.

“If you ever come up with the solution to kickers in the National Football League,” said Sam Rutigliano, the former head coach of the Browns, in September 1984, “you’ll be resurrected. You may be the Second Coming.”

The space between then and now is narrower than it appears. Nearly 32 years have passed since Rutigliano begged for salvation on a Sunday afternoon, after his kicker botched a potential game-tying kick. Yet it sounded so much like yesterday, and today, and, surely, tomorrow.

“Get his ass out of here,” said Snoop Dogg, in a 13-second Instagram screed directed toward the now-former kicker for his beloved Steelers last fall. “Bye, bye, b----. You sorry motherf-----, you.”

Forgiveness extends only so far to the kicker, and sometimes it doesn’t extend at all. Here were the perceived wrongs of the men assailed by Rutigliano and Dogg:

Cleveland’s Matt Bahr was the NFL’s most accurate kicker in 1983. He had won a Super Bowl with the Steelers four years earlier. He was the guy you wanted. In Week 2 of the ’84 season, with the Browns trailing the Rams by three and seconds left on the clock, Bahr lined up a 46-yard attempt. He sliced it wide right. The Browns were 0-2 and would soon be 1-7, at which point Rutigliano lost his job.

Bahr’s steadiness prevailed over Rutigliano’s kvetching, and he was still with Cleveland in 1989, going 7-for-7 in the postseason as the Browns made the AFC Championship Game. He returned to training camp in advance of his 12th NFL season when a teammate approached him. “Hey,” he said. “You better watch out. They’re trying to blame you for the playoffs.” Bahr stared at him. “Why?” he said. “I think I made my kicks in the playoffs.” He had, two field goals and seven extra points.

But there was one game, management remembered, that got away. During a late-season game indoors at Indianapolis, Bahr missed two potential winning kicks—first at the end of regulation, then in overtime, both inside 40 yards. The eventual loss in Indy eliminated the possibility of home-field advantage throughout the playoffs for the Browns (Cleveland eventually finished a game-and-a-half behind Denver). Through circuitous reasoning, the training camp whispers suggested, Bahr had squandered the Browns’ Super Bowl chances.

“If you’re having a rough day, you have to stay with it,” Bahr says. “You have two rough days, you’re getting fired.”

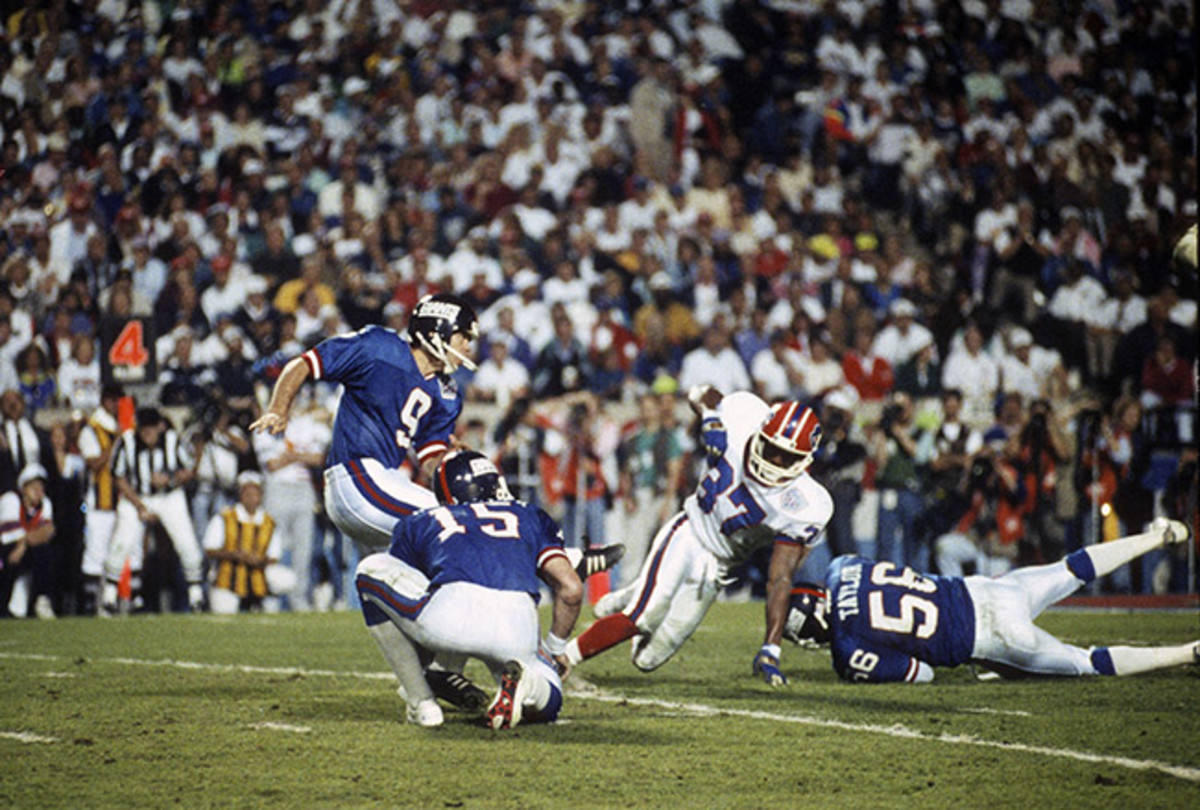

Kickers have the longest average career span, 4.7 years, of any NFL position. They are also the most nomadic players. Bahr’s time was up in Cleveland. The Browns cut him that summer, and the Giants picked him up for the 1990 season. In that year’s NFC title game, Bahr scored all of New York’s 15 points, making five of six field goals—including a 42-yard game-winner as time expired—as the Giants upset the heavily favored 49ers at Candlestick Park. Seven days later Bahr and the Giants won Super Bowl XXV.

The ire of Snoop is easier to recall. In last summer’s Hall of Fame Game, the NFL’s preseason opener, Pittsburgh’s veteran kicker, Shaun Suisham, tore his ACL trying to make a tackle on the second-half kickoff. The Steelers traded for Josh Scobee, who over 11 seasons in Jacksonville had become the Jaguars’ all-time leading scorer. He missed two kicks in his Pittsburgh debut, an extra point two weeks later, and another pair of field goals in a crushing Thursday night loss to hated Baltimore. In that game Steelers coach Mike Tomlin, his team in field-goal range in overtime, a potential 50-yard try for a man who had converted better than 60 percent of his career kicks from 50 yards and beyond, and with the offense sputtering with backup quarterback Michael Vick at the helm, didn’t summon Scobee on a fourth-and-1. Vick misfired. With Baltimore facing a fourth-and-1 within field goal range eight plays later, Ravens kicker Justin Tucker played the hero with a 52-yard game-winner. Scobee was cut two days later. You sorry motherf-----, you.

Context has no say in the tarring and feathering. It matters little that, in that 2010 Chargers-Jets game, San Diego committed 10 penalties, dropped several passes, committed two turnovers, rushed for only 61 yards and missed key tackles, including on Shonn Greene’s 53-yard fourth-quarter TD run. In the annals of Chargers history, the synopsis of that day will put the burden on Nate Kaeding.

“When you miss a big kick,” says Mike Scifres, the Chargers’ longtime punter and holder, “it’s being able to deal with, ‘O.K., what are they going to think of me because I missed that kick?’ Because everybody’s going to point at somebody. And if it comes down to a field goal and you miss that field goal, well, guess who’s going to get pointed at?”

It’s why, as former Packers kicker Ryan Longwell says, perfection isn’t an ambition for kickers—it’s a necessity. It doesn’t matter that kickers were 53.8-percent accurate on field goals in 1965 and, thanks to the position’s dedicated craftsmen, 84.5 percent in 2015. It matters less that they are, more often than not, clutch. A University of Nebraska-Lincoln study found NFL kickers from 1993 to 2009 made 73 percent of attempts that could tie or change the score in the final two minutes of regulation or overtime—six percentage points lower than the accuracy of all other kicks. Acceptable, but not perfect.

In 2015, 70 of the 267 regular-season and postseason games—more than a quarter of them—were decided by three points or fewer, and/or decided in overtime. A single kick can determine whether a team makes the playoffs, whether a coach keeps his job, whether an owner collects postseason revenue. Second chances are frivolous, if not irrelevant. No other position in professional sports demands such flawlessness. There is no depth chart for a placekicker, no backup spots to be had: only 32 openings in the world for the privilege, or pressure.

“You had to be O.K. with missing,” Longwell says. “You had to be O.K. with being the goat, because inevitably that’s the job. All or nothing. There’s no ‘C’ grades in kicking. It’s ‘A’ or ‘F.’”

Kaeding made 86.2 percent of his field goals over his nine-year career. Only five men in the history of football have been more precise. It was, numerically, a B-plus career. But the kicker is loath to settle.

“I regret missing every field goal I ever missed,” Kaeding says. (It is, between the regular season and playoffs, 36 instances of remorse.) “And that may sound impossible, but I wish more than anything that I could have gone out and made every field goal. It’s not realistic, probably not possible, but that’s how my head is wired.”

* * *

“When you’re out there as a kicker, at least for me—I have a real active brain—there’s a lot of weird s--- that goes through your head,” Kaeding says. “Not a whole lot of it overly positive.” That’s why he wonders whether other guys can turn it off. Whether it’s even possible.

It began, for Kaeding, when kicking was less albatross and more enchantment. He was a freshman at Iowa, having grown up in Coralville, a suburb of Iowa City a few miles up Route 6 from the university. His mom, Terry, served Coralville for more than 25 years as a payroll finance officer. His dad, Larry, worked in nearby Cedar Rapids for the city’s water department. Kaeding won a pair of state football championships as the kicker for Iowa City West High. The Des Moines Register named him the 2000 Iowa High School Athlete of the Year. Iowa football coach Kirk Ferentz successfully recruited him. “I hadn’t really had a lot of, like, ‘F---, I-just-fell-flat-on-my-face’ sort of things, and how do I get up?” Kaeding says.

And then he fell: He missed three kicks in a home loss to Ohio State, and his season percentage dipped to 46.7 percent. “It was really the first time you wake up the next morning and you read the paper and they’re like, ‘This guy’s not very good,’” Kaeding says.

He spent much of the next six nights lying awake in his dorm room. More than 95,000 fans awaited him at Beaver Stadium, where Iowa would play its next game against Penn State. He knew the coaching staff could turn to a replacement if the true freshman didn’t find his way. He knew he didn’t have much time. When Saturday arrived, Kaeding jogged out onto the field as State College met the Hawkeyes with thunderous delirium. “F---,” Kaeding thought. “I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

He was as uncertain as teammate David Bradley was assured. The punter had become best friends with Kaeding, on whose Coralville family basement couch Bradley crashed during preseason that year. Violent Midwestern thunderstorms spooked the cellar-dwelling Bradley, who had grown up in San Diego’s arid environs. They never startled Kaeding. “I think everybody in their own way is affected by pressure,” says Bradley, who now works for a Los Angeles real estate firm. “I think the president of the United States is affected by pressure. It’s just about how you channel it. I think Nate was a strong-minded guy at a young age and was mature enough to handle that pressure, and channel it in a way he used it as motivation and positive energy rather than getting clammy hands and shaking in your boots.” Kaeding made four field goals that afternoon at Penn State, including the game-winner in double overtime. In three years’ time, he’d become Iowa’s all-time leading scorer, kick four field goals to win one bowl game and score 13 points to win another.

But success gave his mind little comfort. Such it was for a man trying to perfect something so impervious to perfection. He could never shake the dread of driving into a stadium and wondering whether he’d leave happy. It paraded into his conscience while he sat at his stall before most games. What if you go out and miss five field goals? You’re going to get fired. You’re going to have to move. And your wife… And his kids, then-20-month-old Jack and 5-month-old Wyatt. He would hold them in his arms, and his thoughts would drift to his plant foot, or his rhythm, or what would happen to Jack and Wyatt if he went out next Sunday and shanked a few wide right. It was there even when times were good, when kicks were straight. He’d talk to his wife, Samantha, whom he met in education courses at Iowa, and she’d have to wave a hand in his face to see if anyone was home. He was present and absent all at once, because the pursuit of kicking, Kaeding says, was eroding it all: the enjoyment of playing football, an afternoon with his kids, dinner with his wife. He wondered if other guys can shut it off and live unencumbered.

He tried. At Iowa he started his habit of keeping cue cards with scribbled reminders and healthy thoughts. Slow down. See the ball. Rhythm (1-2-3). He’d review his thoughts and weekly goals the night before games, referencing them again in his stall before kickoff or at halftime. He’d stand on the sideline and allow those fatalistic what if thoughts to consume him. Kaeding wanted to acknowledge those. They were, after all, always there. Then he would do what Bradley says he did so often, and bludgeon the negativity and the pressure and the hypothetical calamity until he was centered once more. O.K., this is an anxious situation. I get it. I understand it. Now I need to get my mind focused on what I need to focus on. I need to calm my mind.

The Chargers video staff created an accumulating highlight reel set to anthemic scores from John Williams and movie soundtracks, showing Kaeding’s best kicks dating back to Iowa City West. He had done this, the highlights showed. He could do it again. During Kaeding’s freshman year at Iowa, a classmate recommended he read “Zen in The Art of Archery” by Eugen Herrigel, a German philosopher and professor who visited Japan to take lessons from an archery master. Kaeding read it in a day and had an epiphany, which he shares today with a handful of Iowa high school kickers whom he mentors: The result, as the master tells Herrigel, should be of little concern. You worry yourself unnecessarily. Put the thought of hitting right out of your mind! You can be a master even if every shot does not hit.

Yet every kick he didn’t make, every time Kaeding had to face his teammates in the meeting room and realize he had let them down—it felt like an arrow to the heart.

Read Part II, “A Lonely World”, and Part III, “Makes and Misses, The End and The Aftermath.”Send questions or comments to talkback@themmqb.com.