A Day with Jared Odrick in Canada’s Counter-Culture

TORONTO — Jared Odrick hails a city cab on Spadina Avenue, the busy main drag of Chinatown, where open sidewalk displays lure passersby to buy fresh produce or bedazzled slippers or bonsai plants. He hops into the car, and gives the driver directions.

“You can make a right on Bloor,” Odrick says, “and go up Bedford.”

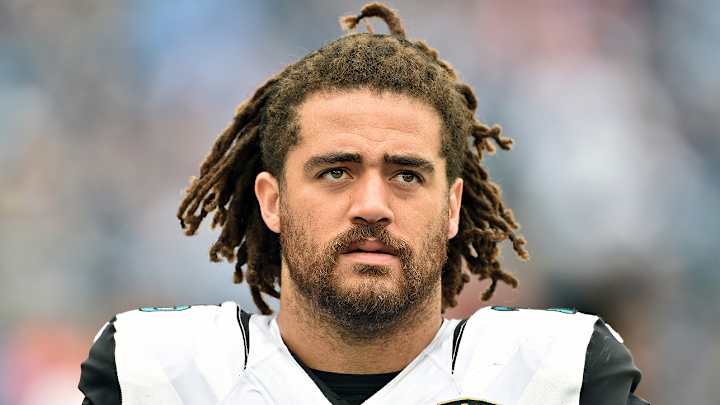

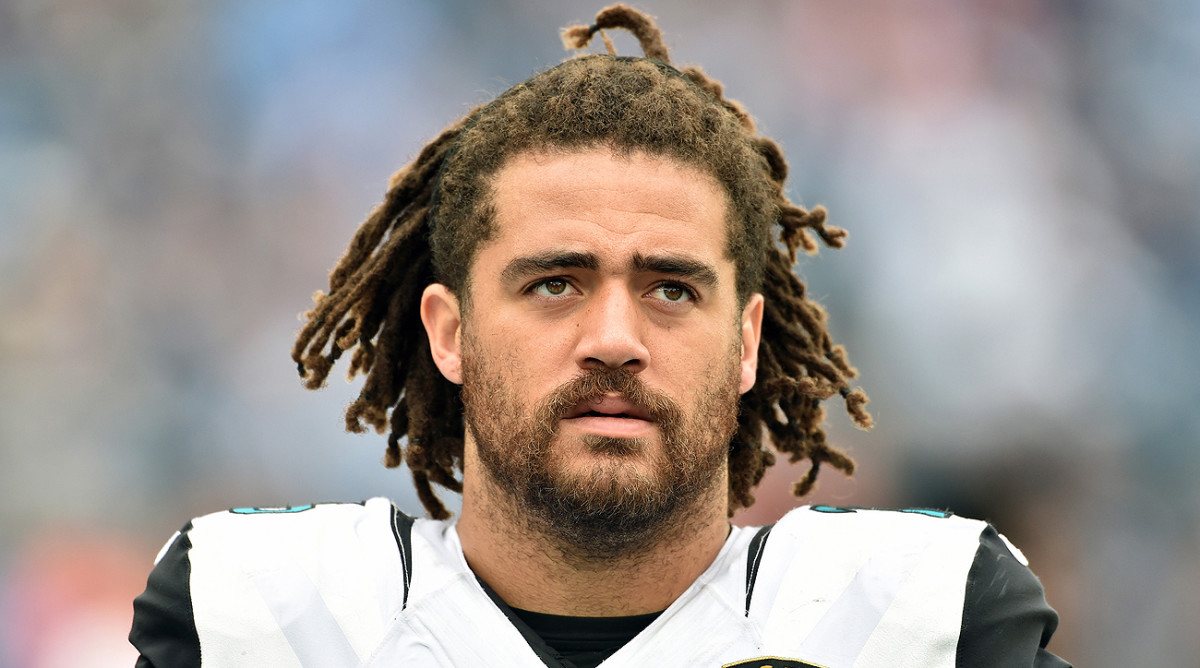

Here in Canada’s largest city, this American football player sounds like a local, because he is one. A few blocks back is the historic row house built circa 1883 that Odrick bought in mid-June, setting a new price ceiling for this neighborhood of Toronto. This is the first property Odrick has ever owned. Not in Miami, where he was a first-round draft pick by the Dolphins in 2010. Not in Jacksonville, where he signed a five-year, $42.5 million contract in 2015 free agency. The 28-year-old Pennsylvania native has found a home outside America and outside football.

“Team sports take away individuality,” Odrick muses as the cab rolls along. “That’s my lead-up to why I’m here in Toronto. I’m doing my own thing, and people think it is so weird when I go back.”

It might sound ironic, but Odrick is breaking out of the football culture to maximize his career as a football player. For the next 12 hours on this day in June, he’ll shuttle between four different appointments as part of a meticulous program to prime his 6-foot-5, 301-pound body for the 2016 season. He’s the kind of guy who approaches life tactically, writing down bullet-point strategies for his goals in life. The time he spends in Toronto is central to his plan for How To Have A Successful NFL Career: Build your own team. Educate yourself.Have a life outside football. Find out more about yourself before you’re done playing.

He leans over and asks the cabbie to take a detour to one of his favorite breakfast spots on Dupont Street.

“People get blinded by the religion of football,” Odrick says. “Players, coaches, fans. But the best way to stay in the business is to keep your personal business running, and the best way to do that is to break some molds. Seek out knowledge on your own. Have individual thoughts. Be a little counter-culture.”

That’s what he’s doing in Canada. As an American citizen, Odrick can only spend up to 180 consecutive days across the border. This was one of those days, a window into the experience that has given Odrick a different frame of reference than many of his NFL peers heading into his seventh professional season.

* * *

10:59 a.m., Rose and Sons

Odrick enters under a retro storefront that simply reads “FOOD,” a sign repurposed from the diner that previously occupied this space, People’s Foods. This is a tiny casual-chic spot, the walls stocked with old books and blackboards listing the daily menu. Odrick has befriended the owner, Anthony Rose, a Toronto chef who has a colony of restaurants all over the city. Rose helps run a summer lunch program offering healthy and locally sourced meals to area kids, and as Odrick puts down roots in Toronto, he’s hoping to lend a hand.

Settling into a wooden booth by the window, Odrick doesn’t glance at the menu. He already knows what he wants: the All-Day Breakfast, with three eggs and bacon—he’s skipping the pork chop today—and the grilled romaine Caesar.

“You have to have fat in the morning,” he says. “That helps your brain wake up and function.”

He follows wellness commandments like this all day. Odrick’s breakfast arrives with a side of potato hash, but he pushes that plate away. He steers away from carbs, especially in the morning, instead choosing breakfast foods shown to boost stimulating neurotransmitters like dopamine. The results: His defensive lineman’s frame has just 12 percent body fat.

Odrick would like to correct the football culture, at least the parts of it reflected in a sign he remembers hanging in the Dolphins training room: “Be a player, not a patient,” a quote from Jason Taylor.

A few weeks ago, the Jaguars’ Instagram account posted a Training Tip of the Week, sponsored by a cold-pressed juice brand: “Pre-exercise meals should be 200-300 calories and 75% carbohydrates and 25% protein.” Even at the breakfast table, Odrick is doing his own thing. When he entered the NFL six years ago, he wasn’t as discerning. He spent his offseasons the way everyone else did.

“My first four years in the league, I went to trainers who trained other big names. I based how good it was off of how tired I was,” Odrick says. “The football tough guy training, flipping tires, etc. Flipping tires is valuable, don’t get me wrong, but it’s the character that guys think it adds. They don’t want to seek out other stuff. They want to be treated like athletes. It’s the football culture.”

Odrick has noticed the difference between team sports and individual sports. He craves the education, and attention, individual athletes receive. So his life in Toronto mimics that. Each of his appointments today is one-on-one, and he’s the only regular NFL client for each of his trainers and therapists.

“If I didn’t meet the people I’ve met up here in Toronto,” he says, “I don’t think I could have gotten my second contract. Not like I did, to be able to play at this level.”

* * *

11:47 a.m. Reach Personal Training

“You have coffee yet?”

Odrick shakes his head no.

“A short is on the way.”

Ben Clarfield, who owns Reach Personal Training, turns to the espresso machine in the kitchenette at his training studio. He adds a pat of butter. (Remember, fat in the morning.) Odrick sips the short espresso shot, then grabs a glass containing a fuschia-colored liquid chock full of amino acids, the building blocks of protein.

“Can we do step-ups and split squats today?” Odrick asks.

The start of Odrick’s Toronto training regimen was somewhat serendipitous. His love affair with the city began with his college girlfriend, a Penn State tennis player, who took him home with her to Canada in 2008. Odrick kept coming back, and during the NFL lockout in 2011, he spent a month staying at her apartment in Liberty Village. Not knowing when the work stoppage would end, he found a local place to train. The first gym he found online was familiar: they had tires, a turf field, etc. But when he got to the front door, it was closed. He pulled up Google Maps on his phone, looking for the next closest training facility. It was Reach.

When Odrick first walked in, Clarfield asked him to do a simple rotator cuff exercise with a dumbbell. He couldn’t do a single rep. “That’s a weak link,” Clarfield told him. “You might want to fix that.” Then, he asked him to do chin-ups. “I’m 312 pounds,” Odrick replied. “I can’t do a chin-up.” Why not, Clarfield asked?

“I’m a starting defensive end, first-round pick, and he’s going to show me up on a rotator cuff exercise?” Odrick recalls. “I can play football, but I wasn’t structurally balanced.”

Now, Odrick doesn’t care much about how much he weighs, or how heavy he’s lifting. His focus is to make his body function optimally—as optimally as it can for someone who has played a brutal sport for the majority of his life. Odrick’s first serious injury happened at Penn State, when he tore the ligaments in his right ankle so violently that the fibula fractured, requiring a plate and six screws to be inserted. Eleven plays into his rookie season in the NFL, he re-fractured the same bone. Two weeks later, Odrick says he found a handwritten note in his locker from then-Dolphins GM Jeff Ireland that included this message: “We drafted you in the first round for a reason. We need you on the field, big guy.” (Ireland, now with the Saints, confirms he often wrote players personal notes, but says his intention was to encourage and keep them connected with the team.)

Odrick took multiple painkillers in order to return the practice field just six weeks after the break. He overcompensated for the right leg, and promptly fractured the fifth metatarsal in his left foot. That series of injuries has had lasting effects he’s still trying to correct today. He’d like to correct the football culture, too, at least the parts of it reflected in a sign he remembers hanging in the Dolphins training room: “Be a player, not a patient,” a quote from Jason Taylor.

“Toughness is recognized more than diligent work,” Odrick says. “I want players to understand how valuable our bodies are and think objectively. Being able to correct things is one of the reasons my career has been able to continue.”

Over the next hour, Odrick goes through a series of “supersets”, tandems of agonist and antagonist exercises repeated five times through. The first one pairs kneeling leg curls, which work the glutes and the hamstrings, with split squats, which work the quads. Kneeling leg curls aren’t popular in the U.S., but Odrick’s team in Toronto swears by them for knee stability—and he recently shared the wisdom with his former Dolphins teammate, Olivier Vernon. There was a play last November in the Jaguars’ game at Baltimore when Odrick was cut by a guard and the center landed on his knee. He ended up only missing a few plays, but the incident looked worrisome even to the Jaguars team surgeon. Odrick’s flexibility and range of motion in his knee may have helped save him from a season-ending injury.

“He snapped his foot in college, so he is never going to be perfect. But we can get close to it,” Clarfield says. “People don’t realize what makes professional athletes different: When they are injured, they keep performing at a high level.”

* * *

1:50 p.m. Bloor-Yorkville

Growing up in Lebanon, Pa., Odrick didn’t know much about Toronto, the capital city of Ontario. The first time he visited, he paused on the sidewalks to knock on the facades of the city’s skyscrapers, in awe of the urban jungle. Now he lives among them, with the 147-story CN Tower visible from his back patio.

The neighborhood he’s walking through now is Toronto’s Fifth Avenue, a high-end shopping district with brick-paved streets. He passes Zaza Espresso Bar, where he usually stops between workouts. The employee behind the counter spots him, and calls out hello. Next door is Trattoria Nervosa, where his usual lunch is a kale salad with grilled tenderloin.

Today, though, he keeps walking, headed to pick up his convertible Porsche from the dealership. The rubber on the front tires had bubbled up, presumably from driving a few kilometers per hour over the speed limit. On the way, he passes the shop where he got his left nostril pierced in January.

“Sometimes, I think, Could I have moved to New York and done this there?” Odrick says. “I don’t think so. Not this exact same perspective. There are things you draw from being outside the U.S.—the actual, physical perspective of being outside the country.”

Odrick calls Toronto “New York without the attitude,” a cosmopolitan city where different cultures, subcultures and races seem to blend more easily. In Jacksonville, he couldn’t roam the downtown without someone stopping him to ask about Dante Fowler, or the team’s draft, or if the Jaguars could really be good this year. The topic he’s been asked about most in Toronto this summer is a very different one.

“People ask me all the time, what’s up with the guns in America? Why do you feel the need to have a gun on your body?” Odrick says. “It’s a gun culture, because it’s always been a gun culture. It’s the same thing with race; it’s what the country was built on. America was built on the backs of slaves. Canada always represented something else.”

* * *

3:15 p.m. Reach Personal Training

Odrick puts up the top on his Porsche and pays a parking meter. His regimen includes 10 shorter workouts per week. Now he’s back for Round 2.

Earlier, he was training alongside a 14-year-old girl exploring weightlifting and a man in his 60s. Sometimes, the NFL-sized Odrick feels like a bull in a china shop. This afternoon, he has the place to himself, so he puts on a chopped and screwed mixtape of Tame Impala, an Australian psychedelic rock band. He starts with “duck” and “lizard” exercises, in which he drags his body along the floor in strange contortions mimicking the animal of choice. “Because he will get caught in weird positions on the field,” Clarfield explains.

Odrick had just returned from Jacksonville, where he’d participated in the team’s mandatory mini-camp, but he spent most of the team’s offseason program training on his own in Toronto. Offseason workouts are voluntary in the NFL, but there’s often tacit disapproval from coaches, media and fans when players don’t report.

“Last year, people thought I was the crazy guy coming to the Jaguars,” Odrick says. “He’s going to sign this big contract, and go up to Toronto to train? Yes, because it is in my best interest. But it’s against the football culture. Why do you need to be different?”

“I’m trying to come up here,” Odrick says, sitting on a park bench in Toronto, “so I don’t have an identity crisis when I’m done [playing football]. That s--- is PTSD.”

Three weeks into first his offseason in Jacksonville, Odrick explained to the Jaguars coaches why training in Toronto would best prepare him for the season. Every player’s body, and injuries, are different. A workout plan created for a roster of 90 players wouldn’t be as individually tailored as the program he has in Toronto. For example, it wasn’t until a few years into Odrick’s NFL career that he learned his right leg was longer than his left one, likely due to his surgery in college. His training program accounts for that imbalance with a lot of single-leg exercises.

His coaches trusted him to do his own thing that first offseason, and it paid off with a season of results. Odrick started all 16 games and led the Jaguars with 5.5 sacks as a two-gap lineman who is often asked to read and react instead of shooting upfield. And he did so without taking any painkillers or shots all season long—a rarity for a veteran lineman in today’s NFL. His new teammates voted him to be their union representative. This year, he has hopes of being voted a captain.

“I’m not anti-team; I’m pro-team. And I’m pro-player,” he says. “Guys are scared to say something; they’re scared to stand out. Even the guys who have the clout to say something, they are scared to have individual thoughts. I think sometimes we forget we have this awesome opportunity and platform, but we also have a responsibility to ourselves to extend our careers and make something for ourselves afterward.”

* * *

4:19 p.m., GoodLife Fitness

Odrick is running a bit late to his next appointment. If there’s one thing he doesn’t like about Toronto, it’s the maze of downtown streets that prohibit turns. The next member of his team, Brad Cote, is waiting in the lobby of a multi-level fitness center on Yonge Street to take him downstairs to a treatment room.

Cote is a personal trainer and registered massage therapist fixated on fine-tuning the mechanics of Odrick’s body. He flew down for Jaguars mini-camp, hoping to better understand Odrick’s movement patterns by watching him practice. Today he’s combining a few treatment methods, including something called fascial stretch therapy.

“Muscles should slide like two sheets of paper,” Cote explains, as he pushes and pulls on Odrick’s left leg from a variety of angles. “Now picture glue between the sheets of paper so they get stuck. I try to find spots where it gets stuck and doesn’t move as well and you have to compensate. When you’re an athlete at a high level, there’s a smaller optimization window. If things don’t work optimally, you get a breakdown that can lead to injury, and that can limit your career.”

The first 80 percent of changes to your body are the easiest; the last 20 percent is what they’re working on now. Of particular interest to Odrick this summer is something that sounds very subtle if you’re not a pro athlete: The tracking, or motion, of his left knee. Ever since he broke the fifth metatarsal in his left foot in 2010, his foot feels thick around the screw that was inserted in that bone, and he’s been hesitant to place pressure on it. That’s resulted in a pattern of his knee falling inward, and some pain in his quad.

“I felt the knee a little bit on the sled today,” Odrick reports. At mini-camp, Cote watched how Odrick loaded his left leg when he got in and out of his stance. They wanted to teach him a new movement pattern, and get it to stick.

Odrick looks up from the treatment table. “I’m sure 90 percent of players in the league aren’t having these kind of conversations,” he says. “My rookie year, because of the loading pain in my knee, walking up and down stairs was really hard. I used to be scared to walk up and down stairs in front of coaches. We learn to be tough and grit it out and not have teams spend more money than they need.”

The session ends after an hour. The work is laborious, and Cote’s red polo shirt is soaked in sweat.

* * *

6:43 p.m. Trinity Bellwoods Park

After a brief stop at his new home to let in his interior decorator—the place is largely unfurnished, save for a bed and a giant Fatboy beanbag downstairs—Odrick roams over to Toronto’s Queen West Village. He walks past a bar where he went solo for a drink the other night, and he’s got a story. He met a woman there whose friend was seeking a model for her clothing brand. “You match the aesthetic perfectly,” she said. Might he be willing to take a trip to some nearby sand dunes for a photo shoot? Odrick shrugged yes.

“I feel like Bill Murray in Lost in Translation. Meet a girl, have an experience,” Odrick says. “Someone asks you to do a photo shoot, and you don’t get judged. If I did a photo shoot in Jacksonville, your teammates would fry you up. Heck, I’d fry me up. Here, you chalk it up to an experience.”

The previous weekend, Odrick had been invited back to Pennsylvania as a chairman of the Big 33 game, a high school all-star game between the top players from Pennsylvania and Maryland. His speech to the players and their families the night before the game drew on the perspective he’s gained in Toronto. “You have to develop your social complexity,” he told the players. “Football is going to run out for you. It is going to run out for me.”

That’s a reality he faces head on. In the past year, Odrick has been involved in the production of two short films, and acted in one. He’s visited Iceland, Amsterdam and the Dominican Republic; last spring, he waited out free agency in Tanzania. Here in his adopted city, he likes the fact that the only time he’s been recognized as an NFL player is by the general manager of the Toronto Argonauts.

“I’m trying to come up here,” he says, sitting on a park bench across from a group of hula-hooping ladies, “so I don’t have an identity crisis when I’m done [playing football]. That s--- is PTSD.”

* * *

8:15 p.m. Downtown waterfront

Fresh off a flight from London, Stephanie Canestraro is fighting off jet lag to set up a treatment table in the living room of her lakeside condo. She just spent a week in Manchester, where she was working a hypertrophy (definition: the growth in size of muscle cells to increase muscle mass) camp with Charles Poliquin, a top international strength coach. Odrick is so committed to her treatment sessions, he flies her down to Jacksonville eight times a season, spending $1500 per visit.

She is a chiropractor and functional integrated therapist, meaning she’s been trained in a combination of techniques to improve soft tissue, joint and nervous system function. Over the next two hours, she’ll use four of these techniques.

Canestraro starts with passive release stretching, rattling off questions and observations as Odrick lays on his back. Your knee is tracking better. You’re tight on your outer quad here. How is your lower back? “These are all subtle things,” she says. “I can get his body moving better, but then his training has to match.”

She follows what she feels with her hands, looking for spots of tension. With her next technique, biomedical dry-needling, she’ll insert needles at those spots, creating a small inflammation that will signal to the brain to send blood and oxygen to this area. The body’s natural healing process is triggered locally, reducing pain and generating healthy tissue that won’t injure as easily. Next, she gets out electrodes and uses the needles to send electrical impulses into muscles. Odrick’s tight outer quad starts twitching.

“A lot of guys think this is too much,” Odrick says. “They say, You’re trying too hard. I feel like it is a necessary process to being a pro athlete.”

When an Uber Eats delivery arrives, they take a break. Odrick is a regular customer of Impact Kitchen, a Toronto restaurant whose menu offers a food philosophy of eating minimally processed foods and embracing healthy fats. He orders two power bowls, a mix of vegetables and sweet potatoes, one with steak and one with chicken. For a late-night snack, there’s some beef jerky—the organic kind.

Odrick estimates he spends about $200,000 per year on his personal training and therapy regimen, but the payoff was his second contract. And, he hopes, a third one.

“Physically, I feel I am not as worried,” Odrick says. “There were times in my career when I was worried something would not work, or something would go out. The more treatment I got, and the more educated I got, I feel like I can overcome things. I feel less vulnerable. I do have pain, but there are better ways to attack it than ice, stim(ulation) and painkillers or injections.”

“I used to have a love-hate relationship with football,” he continues. “I had anger toward the NFL. After I broke my leg and foot in my first year, I was treated totally differently. They gave me tickets to games. Being called a bust after one year. I never got the benefit of the doubt. I drank more often my first three years, and I was angry. What is my value? What is my worth? Gaining perspective made me way less angry.”

It’s a perspective he’s trying to share. Before the Jaguars dispersed from minicamp for the summer break, coach Gus Bradley asked a few of the veteran leaders to speak to the team about how they prepare for the season. Odrick talked about Toronto, and the team of professionals he’s built for himself in his adopted city. Growing up in the income classes many of us grew up in, no one ever taught us to reinvest in ourselves, he told his teammates. But that’s how you raise your odds of being able to extend your career. When Canestraro comes down to Jacksonville to work with Odrick, he has a standing offer for his teammates to try out a session with her, too.

After dinner, Canestraro pulls out a small ultrasound machine. The high-frequency shock waves penetrate deep below the surface to break up scar tissue, reduce pain and stimulate healing. She uses the wand to work on that six-year-old foot injury. Odrick stands up against her kitchen island, pushing the outside of his left foot against her hand. After a few minutes, he shakes out his foot and smiles. He can put pressure on the outside of that foot, right on the screw, without feeling his knee falling in. This day in Toronto is a success.

Odrick slips on his white canvas Tretorn sneakers and requests an Uber. “Kevin” will be arriving in six minutes. Canestraro starts to ask which Airbnb he’s headed back to, before remembering he just closed on his new place. Arms spread wide, he grins and bellows: “I’m home, baby!”

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.