Welcome to Goodell Week

With Peter King on vacation until July 25, this week’s Monday Morning QB guest columnist is Pro Football Talk founder Mike Florio. Peter and Mike work together on NBC’s Football Night in America on Sunday nights during the season, and Mike also hosts PFT Live weekdays on NBC Sports Radio. Mike previously practiced law for 18 years and is active on social media. Follow Mike here.

By Mike Florio

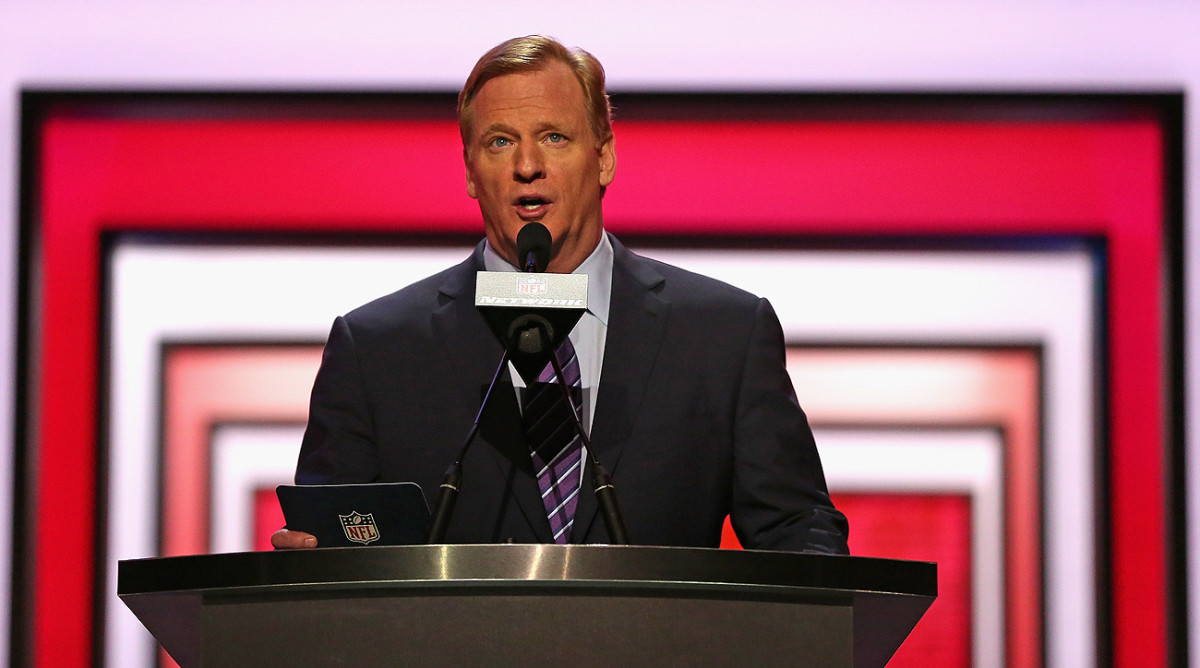

Heavy is the head that wears the crown, and even heavier is the wallet of the man who makes more than $30 million per year. But Roger Goodell has a thick neck and a strong core and bank accounts big enough to absorb the money he makes as he presides over the greatest sport on the planet. Whether the boss is getting paid like a boss because of: 1) his managerial skills; 2) the $13 billion in annual revenue the league generates; 3) the fact he’s the one who absorbs the scrutiny that otherwise would be directed at owners pulling levers and pressing buttons while Goodell exclaims, “Pay no attention to those men behind the curtain!”; 4) some combination of the first three, he’ll be earning all (or at least part) of a salary that puts him millions of dollars ahead of the sport’s highest paid player.

It’s Roger Goodell Week at The MMQB, with the next five days featuring several articles and discussion centered around the NFL’s leader 10 years into his commissionership. I’ll get things started by looking at the things Goodell could be (or should be) concerned about at this point in his tenure.

• PREVIOUS MMQB GUEST COLUMNS: Lions guard Geoff Schwartz || Former QB Jake Plummer

So here’s everything I could think of based on 43 years of being a fan of the NFL, 16 years of being in the business of covering the NFL, 10 years of doing it on a full-time basis, and seven years of reading, talking, writing, and thinking about the NFL as the only thing I do, pretty much during every waking moment from late July through early May and much of the time during the few slow weeks in between.

1. Quarterback play

Most regular-season and postseason games produce a handful of memorable moments. Even the exciting games have long stretches of back-and-forth nothing. For some teams, the offense simply lacks the ability to take full advantage of rules aimed at generating yardage and points and, ultimately, excitement.

For the teams that can’t gain ground on the field or pump up the numbers on the scoreboard, the reason often is subpar quarterback play. Whether college coaches aren’t using pro-style offenses or NFL coaches are trying to force a quarterback into their “system” instead of figuring out what he does well and doing that or owner impatience with coaches becoming coaching impatience with the quarterback, the supply of competent quarterbacks in the NFL doesn’t match the demand. This makes it hard to have true competitive balance, which is ultimately what the NFL craves.

Goodell and the NFL need to be actively searching for ways to find NFL-caliber quarterbacks and to help them improve, from using Virtual Reality training on a constant basis to increasing the time coaches and quarterbacks may directly work together in the offseason to instituting a minor league system that would give young quarterbacks live reps in a game setting.

NFL teams also need more coaches who are willing to choose what works over what they want to do. Too many insist that players conform to the playbook; not enough make the playbook fit their players. By the time a quarterback gets to the NFL, it’s too late to change him—and it’s asinine to not embrace the style of play that got him to the NFL in the first place.

So maybe the problem isn’t only that there aren’t enough good quarterbacks to go around. Maybe there aren’t enough good coaches to get the most out of the quarterbacks. Or maybe there aren’t enough good scouts to discover the quarterbacks with the highest ceilings. Or maybe there aren’t enough owners who know how to find the coaches and scouts needed to best do the job.

Whatever the problem and however it gets solved, that’s the top competitive concern for the league moving forward. And it’s the first point that should be raised if anyone ever suggests expanding the NFL beyond 32 teams.

2. Safety issues

Before October 2009, player health and safety didn’t occupy a central spot on the NFL’s radar screen. Then came a House Judiciary Committee meeting, with California representative Linda T. Sanchez saying this: “The NFL sort of has this blanket denial or minimizing of the fact that there may be this link [between football and future cognitive impairment]. And it sort of reminds me of the tobacco companies pre-’90s when they kept saying, ‘Oh, there’s no link between smoking and damage to your health.’”

The NFL got the message; if the league didn’t address the issue, Congress would. And so, virtually overnight, the league beefed up its concussion protocols, with the goal of getting concussed players off the field and keeping them there until cleared. Likewise, efforts were made to reduce the number of blows to the head, with the term “defenseless receiver” entering the media and fan lexicon.

Less than a year later came restrictions on offseason programs and training-camp practices, with two-a-days going the way of the dodo bird. The owners, intent on getting a great financial deal from the union to end the lockout, gladly agreed to these concessions. Some like Lions guard Geoff Schwartz in this space a week ago would say that it has cost the game plenty, with players less prepared to master fundamentals like blocking and tackling once the regular season starts. Regardless, the game necessarily became, on a broad level, safer.

And now some players are walking away from the game before the game walks away from them, sparking concerns that eventually there may not be enough capable players to fill out 32 NFL rosters. The league needs to be concerned about the supply of players being choked off from below, with more and more kids opting for other sports and never becoming football players.

The funnel nevertheless remains steep and narrow, and major colleges will be handing out scholarships to athletes who are deemed good enough to play football at a high level even if they previously never have. For young adults who otherwise can’t afford to go to college, the prospect of a full ride in exchange for giving football a whirl will be too hard to pass up.

Still, the NFL will have to find a way to make the game as safe as possible without fundamentally changing it. Currently the kickoff sits in the crosshairs of that effort, but the lack of a clear solution shows how delicate the process of striking the right balance on an ongoing basis will be.

At some point the right balance could be impossible to strike. If a test for detecting Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in living patients ever is developed and if it reveals widespread CTE among NFL players and those at lower levels of the sport, tackle football could go the way of two-a-days, with two-hand-touch becoming the new norm.

3. Legal concerns

The NFL has escaped the thousands of concussion lawsuits brought by former players with a settlement that, on one hand, pales in comparison to the potential verdicts that could have been entered against the league. On the other hand, the NFL had a long list of legal roadblocks that could have been used in defending the cases, any one of which could have delivered an outright victory against arguments that the league deliberately concealed the real risks of concussions and failed to do enough to protect them from harm.

Ideally, the league should scrap the entire officiating function as it was first conceived and ask itself this question: How should we best monitor the action and decide what actually has happened during a given play?

Although it’s now impossible for any player to claim that anything about the risks of concussions isn't known, players could contend that the league and/or the union have failed to take proper steps to protect them from harm (for example, by not getting rid of “the most dangerous play in the game”) or by failing to get them off the field when concussed (e.g., Case Keenum) or by otherwise not eradicating a culture that results in plenty of coaches pressuring players to play.

A nationwide class action targeting all 32 NFL teams regarding the use of painkillers could put that play-or-else culture in the spotlight, with allegations that coaches like Don Shula and Mike Tice threatened to cut players who didn’t use potent drugs to mask pain and play. With the case surviving an initial effort to throw it out of court, the league will have to provide information, documents, and testimony regarding whether and to what extent players were informed of the risks of using these medications and/or threatened to take a shot of Toradol or hit the road, Jack — which could make settlement even more prudent than it was in the concussion lawsuits, which were resolved before they ever got to the “discovery” phase, when evidence potentially supporting allegations of wrongdoing is harvested.

4. Officiating flaws

The NFL started nearly 100 years ago, before TV and long before the advanced technologies that are both prevalent and cheap in 2016. Players were smaller, slower, and not nearly as strong. They wore pads that were closer to padding than armor. Sprinkled among them were men charged with applying the rules and keeping order.

Over time, everything about the game has gotten bigger, faster, more intense. And yet the league still adheres to the same approach to officiating as always: Put several folks in black and white stripes, throw them into the fray, and hope that while honoring their self-preservation instinct they’re also able to notice with precision the things flashing by in front of them.

Mistakes are inevitable. Really, it’s amazing more aren’t made considering the speed of the game and the complexity of the rule book. But the mistakes have now become more obvious, given the battalion of cameras blanketing the field and broadcasting images on high-definition flat screens to millions of homes, followed instantaneously by the dissection of every blunder on social media.

The league has begun to bridge the gap between what the officials see with the naked eye once and what the rest of us see in magnified super slow motion, repeatedly. With a pipeline in place from 345 Park Avenue to ensure consistency in the application of the replay review process, V.P. of officiating Dean Blandino can play the role of Cyrano on a wide variety of issues and ambiguities and flat-out errors that would otherwise be uncorrected.

Earlier this year, the NFL embraced use of that communication device for administrative matters. The rule was written vaguely, which potentially allows Blandino to buzz a referee and tell him that it’s obvious based on the images being currently projected to the world that a mistake was made.

Some will object to the ability of the league office to overrule game officials beyond the boundaries of the formal replay process, but I’ve got no problem with it. The goal should be to get as many calls right as possible.

Ideally, the league should scrap the entire officiating function as it was first conceived and as it has evolved and ask itself this question: How should we best monitor the action and decide what actually has happened during a given play?

If that ever happened, a far different, and potentially far better, procedure potentially would emerge.

5. Labor problems

In the blink of an eye, that 10-year labor deal resolving the 2011 lockout has reached the halfway point of its existence. Five years from now, another lockout (or a strike) could happen.

The relationship between the NFL and the NFL Players Association seems to be rockier than ever. Players don’t trust the league office, thanks to controversies like the Saints bounty scandal and Deflategate. The union likewise doesn’t trust the league, believing management makes promises it can’t or won’t keep.

Perhaps the biggest threat to the relationship happened earlier this year. The NFLPA caught the league with its hand in the proverbial cookie jar, diverting revenues that should have been shared under the salary cap into made-up exceptions so clearly inappropriate that a neutral arbitrator ruled in the union’s favor at the conclusion of the hearing, without even taking the matter under advisement for further study. The players believe that an attempt was made to steal their money, which could make it very hard to restore the level of trust necessary to hammer out another long-term contract.

Come 2021, the league will want the players to agree to tactics for growing the pie (such as more regular-season games and an expanded postseason), and the players will want to increase the size of their piece of it. Other issues like Commissioner powers and marijuana could creep into the talks. When a labor contract expires anything and everything about the relationship becomes fair game for discussion and negotiation.

During the lockout, the players ultimately decided not to give up game checks, accepting the last, best offer that was on the table before real money would be lost. The next time, could the players feel differently about taking all or part of a year off?

6. Team and player discipline

Not long after Roger Goodell succeeded Paul Tagalibue as commissioner, agents began to grumble about the hard line the league office suddenly was taking regarding alleged violations of the substance-abuse and PED polices. Reasonable compromises no longer were available as the NFL took full advantage of its final say to impose its will on players.

Somehow, Goodell was persuaded in 2014 by the union to relinquish his power over these matters to neutral arbitration. But he still retains judge/jury/executioner status on matters relevant to the integrity of the game, the principle that fueled the Deflategate controversy. Over the 32 teams, Goodell’s power remains absolute. He imposes the discipline and handles the appeal, giving the member clubs no real recourse.

The disciplinary power over players and teams in a non-drug/PED setting has been used several times in recent years, creating results that seemed to some (especially the team and players involved, and their fans) objectively unfair. Some of these cases include the salary cap penalties against Dallas and Washington in 2012, the Saints bounty scandal, Deflategate and more.

All too often, the league office ignores evidence that a violation may be cultural, opting to single out one team, make an example of the alleged culprits, and scare straight every other team that is doing the same thing. In scrapping the player suspensions imposed for the bounty scandal, Tagliabue (appointed by Goodell as the arbitrator under pressure from lawsuits challenging Goodall’s neutrality) made an eloquent but pointed case for properly addressing rule breaking that isn’t isolated to one team.

Tagliabue’s case for making cultural changes reflects a much a better way to do business when it comes to discipline and rules violations. It’s far more fair and just to all players and teams. But the league office stubbornly insists on retaining the ability to do what it wants, when it wants, how it wants, disregarding reasonable and persuasive arguments for a more balanced and neutral approach. Unfortunately for the league, this approach has alienated the union, many players, and entire fan bases that will forever believe their favorite team got screwed.

If the league office ever chooses to opt for self-awareness on these issues, here’s the only question that needs to be asked: Is having and using (and potentially abusing) that kind of power over teams and players really worth the damage that has been done to the underlying relationships?

7. Broadcasting strategies

The NFL’s current TV deals last until 2022. After that, no one knows how live game footage will be distributed. The league ultimately will need a plan that sustains, and maximizes, the billions of dollars it receives by selling those rights on the open market, while also minimizing any collateral damage.

Plenty of options exist. With Yahoo, YouTube, Twitter, Amazon, Netflix and other digital options either at the table or inching closer to it, the league will use the power of Big Shield to squeeze multiple companies into once again paying absurd premiums for the ability to use NFL games as a tool both for making back a large portion of the rights fees via advertising and/or subscription fees while also heavily promoting other content available through the platform.

If the NFL ever makes the game “too safe,” an opening could emerge for an old-school football league that embraces rules the NFL has ditched and markets it to the same folks who gladly lap up UFC-style brutality.

No one knows what it will look like. The cord-cutting phenomenon will make it very difficult for ESPN to once again increase its $2 billion per year ante; if that money won’t be coming from ESPN for Monday Night Football, who will replace it?

And what if the steaming services offer millions more than NBC, CBS, FOX, or ABC for Sunday afternoon or other prime-time packages? If the NFL dramatically reduces its presence on over-the-air, free TV (which is still used by millions of Americans as their sole gateway to TV content), Congress could remove the broadcast antitrust exemption, a legislative vestige of the ‘60s that allows the league to sell its games as a package—preventing, for example, the Cowboys or Patriots from doing a Notre Dame/NBC package and far less popular teams from fighting for scraps on fringe networks.

Like the consumer, which now has many more choices than the three-network 1970s, the NFL has many more options. The league will need to do the right deals to replace the current ones, finding the best balance between making the most money, generating the biggest audiences, and keeping Congress out of the league’s backyard.

8. Revenue sharing

Prior to the 2006 and 2011 Collective Bargaining Agreements, revenue sharing occupied a spot high on the list of the league’s problems. Some revenues that the franchises weren’t splitting among themselves nevertheless were included in the broader pot that determines the salary cap, artificially increasing the labor costs of the teams that making less money in their local markets.

The 2006 CBA created a convoluted system of supplemental revenue sharing, which allowed certain teams based on need to get even more of the shared revenues in order to make up for the cap disparities created by unshared revenues. After the 2011 CBA, the issue disappeared so quickly it was like it never even existed. The union doesn’t know where these nuances of revenue sharing stand, the media doesn’t know where they stand. No one beyond the walls of the NFL knows where they stand.

Is it a problem? Is it not a problem? If the broadcast antitrust exemption ever goes away, it will become a major problem, since a small handful of teams with national following instantly will be making the vast majority of the broadcasting money. If those teams can’t be persuaded to continue to operate as socialists in a capitalistic country, it could be hard to keep all 32 teams on the same page and, over time, in the same league.

Even with the broadcast antitrust exemption still in place, differences remain between what some teams make and what other teams make. As the cap keeps spiking, those differences eventually will emerge as a hot spot for the league at large.

9. Stadiums

Most teams use their stadiums 10 times per year. And yet many stadiums become obsolete within 20 years after they had a bottle of champagne busted against the hull. The problem isn’t that the stadiums have become dilapidated (however, FedEx Field seems to be getting close after only 19 years) but that the newer, swankier stadiums put pressure on teams with older stadiums to modernize.

When Jerry Jones opened the Cowboys’ current home in 2009 (yes, it’s already been that long), other teams became inspired to follow suit with impressive, space-age venues. This year, the Vikings will launch a new, futuristic venue that is both enclosed and flooded with natural light. The Falcons in 2017 will play inside a complex structure with a roof that opens and closes like a giant steel change purse. Two years later, the ribbon will be cut on Kroenkeworld, the $2.5 billion structure that will house the Rams (and maybe one more team) and increase the pressure on the other NFL franchises with older structures to finagle something nearly as good, or maybe even better.

For the cycle to continue, it will have to happen at least for now without much if any public money. Sure, the folks in Las Vegas will be willing to kick in a large chunk of taxpayer change, primarily as a tax on legitimizing Sin City. Beyond that, the league will have a hard time finding communities willing to subsidize billionaires.

After 20 years of franchise stability, relocations could happen more frequently. If, after all, a team will be required to pay for its own stadium, why wouldn’t that stadium be built in a larger market, featuring more money and more people to give up that money? Also, the fact that St. Louis tried, and failed, to keep the Rams despite a large public contribution will make elected officials in other cities more reluctant to expend political capital for a potentially losing effort.

Apart from building stadiums, the league will have to figure out how to keep all stadiums full on a consistent basis. The in-stadium experience needs to be sufficiently better than watching the game at home, which is becoming for many the best way to take in a full day of football. With the blackout rule likely off the table for good, all teams will need to find ways to fill the stands, and only so many will be able to use winning as the primary attraction.

10. Competitors

After the draft and with no lingering stories or controversies or other reason to obsess over the NFL in the slow months, the nation’s attention turned to other sporting events. The NBA became the primary beneficiary, with the spike lasting beyond the NBA Finals and into the launch of free agency.

There’s no match in America for the NFL from August to February, and there likely won’t be. Other football leagues have tried from time to time to steal a portion of the NFL’s thunder, but they always fail. Still, if the NFL ever makes the game “too safe,” an opening could emerge for an old-school football league that embraces rules the NFL has ditched and markets it to the same folks who gladly lap up UFC-style brutality.

As it sits atop the American mountain, the NFL covets an even higher summit: Development of the same popularity in other countries. England and the rest of Europe provided the natural starting point toward eventual global domination; China is the white whale, where 1.3 billion potential football fans reside.

So the league’s true competitors aren’t other sports leagues or other football leagues. The NFL’s current competitors are those things currently attracting the money and attention of people in these other countries. Over the next 50 to 100 years, the league fully intends to overcome international sports like soccer in the same way it surpassed baseball domestically.

It may not succeed in that objective, but it will get even richer trying. Eventually, those international gains could help make a billion-dollar operation into a trillion-dollar global enterprise.

* * *

Eric Berry and franchise tag thoughts

Deadlines drive action in the NFL, but there wasn’t much driving being done Friday, when the deadline came and went for signing franchise-tagged players to long-term deals.

Last year, all of the tagged players except Jason Pierre-Paul (for obvious reasons) got multi-year contracts. This year, Chiefs safety Eric Berry, Rams cornerback Trumaine Johnson, Bears receiver Alshon Jeffery and Washington quarterback Kirk Cousins will spend 2016 under one-year contracts.

The lack of deals flows largely from the revised formula for determining the franchise tag. No longer determined by averaging the cap numbers of the five highest-paid players at the position in the prior year, the franchise tag is now calculated by taking the tag amounts at a given position for the past five years, adding them together, and dividing the sum by the total combined salary caps for the last five years. The resulting percentage is then applied to the current year’s salary cap.

In English, this means the tag for each position has settled on a specific percentage that has essentially locked into place. As the cap goes up, the franchise tag will go up, regardless of what the market does.

That’s why, for example, Chiefs safety Eric Berry will make $10.8 million this year—an amount more than any other safety will earn in 2016 on a multi-year deal. Over the last five years, the franchise tag for safeties has accounted for 6.95 percent of the salary cap. The market at the position hasn’t kept.

That’s also why the Chiefs and Berry didn’t work out a new contract; with $10.8 million in the bank for 2016 and, by rule, a 20-percent raise next year if the Chiefs tag him again (i.e., $12.96 million), Berry had no reason to accept anything less than the sum of his 2016 and 2017 tag amounts as fully-guaranteed payments at signing. Given the league-wide market at the position, the Chiefs felt no compulsion to give Berry $23.76 million fully-guaranteed at signing.

As a result, Berry will play this year under the tag. Next year, the Chiefs will tag him at $12.96 million (less likely) or let the actual safety market determine his value (more likely).

As to the deadline-day deals that got done this year, both the Jets and Ravens gave defensive lineman Muhammad Wilkerson and kicker Justin Tucker, respectively, more over the first two years than they would have gotten under two years of the tag. (Von Miller’s deal wasn’t driven by the tag; more on that later.) For Berry, Johnson, Jeffery, and Cousins, it was a simple case of their teams not being willing to guarantee the tag amount plus a 20-percent raise for next year.

And that reluctance was driven by a simple case of the growth of the tag at those positions not reflecting the growth of the market.

* * *

Washington confident it can find another Cousins

When Washington used the franchise tag on quarterback Kirk Cousins, the team guaranteed that he’ll make $19.95 million in 2016. But, as Mike Garafolo of NFL Media explained it, Washington’s best offer on a long-term deal for Cousins was never more than $16 million per year, with $24 million guaranteed.

That offer came way back in February, before Washington applied the tag to Cousins. After applying the tag, and after the Eagles gave Sam Bradford $17.5 million per year and the Texans gave Brock Osweiler $18 million per year, Washington never improved its offer to Cousins, at any time.

It’s not easy to reconcile the team’s willingness to give Cousins nearly $20 million guaranteed for one year but only $24 guaranteed on a multi-year deal. The answer resides in G.M. Scot McCloughan’s quiet confidence that he can find another quarterback with comparable skill for a lot less money.

Cousins wanted $44 million fully guaranteed at signing, roughly the sum of what he would have made under the tag this year ($19.95 million) and next year with a 20-percent raise ($23.94 million). Instead of paying Cousins that much money now, Washington can pay him the $19.95 million now and, if he plays well against this season, the $23.94 million next year. Then, come 2018, Washington will either sign him to a long-term deal based on his open-market value (whatever it may be), use the tag a third time (which is unlikely, given that he’d get a 44-percent raise to $34.47 million), or let him leave and replace him with someone who has been groomed to take over.

The team believes that, by 2017 or 2018, it will have found a quarterback on a slotted, low-money rookie four-year deal who can do what Cousins does, or close to it. That could be 2016 rookie sixth-rounder Nate Sudfeld, or it could be someone else. Regardless, Washington believes that someone younger, cheaper, and just as good if not better can be found, if Cousins still insists after 2016 or 2017 on breaking the bank.

The process definitely entails risk, both that they’re paying Cousins too much this year (e.g., the Ryan Fitzpatrick phenomenon) and that they won’t find someone as good or better. Regardless, with a $19.95 million bird in the hand, Cousins had no reason to accept the offer on a multi-year contract. Now, the challenge for Washington will be to go find its two in the bush, before Cousins flies away.

* * *

Von Miller could have gotten more next year

In 1998, the NFLPA first added to the labor deal a provision that prevents a team from using the exclusive version of the franchise tag a second time if an exclusively-tagged player sits out the entire season. Eighteen years later, the previously little-known tweak became a major factor in negotiations between a team and a tagged player.

With the non-exclusive franchise tag for linebackers equaling the amount of the exclusive franchise tag ($14.129 million, because the growth of the tag has outpaced the growth of the market), it was smart for the Broncos to use the exclusive version on Miller. Otherwise, another team could have loaded up a mammoth offer sheet and happily given up a pair of first-round picks for the guy who seemingly single-handedly delivered a Super Bowl appearance and victory. But with Miller able (and apparently willing) to sit out the full season and be swiped for a first- and third-round pick in March, the Broncos had to do much more than simply offer a contract based on the amount of the franchise tag in 2016 and 2017.

The Broncos had to get much closer to market value, or Miller could have waited until March and gotten much more. Even with a six-year, $114.5 million contract that includes $70 million in guarantees that most likely will be earned, Miller could have gotten more from another team if he’d opted to not play in 2016.

He’s a unique defensive weapon, able to rush the passer, cover receivers, and essentially play every position except nose tackle. The Broncos surely wouldn’t have won a championship without him, and other owners would have regarded him as a guy who could bring a Lombardi Trophy to town.

As Mike Klis of 9news.com reported Saturday, at one point in the discussions Miller’s agent, Joby Branion, requested permission to seek a trade right now. When the Broncos refused and likewise held firm on a bottom-line offer from July 7, Miller had to decide whether to take the deal or sit out an entire season.

In the end, Miller took the deal, even if he could have gotten more in 2017. It was the threat of siting out that helped him get what he ultimately got, the best contract ever given to a defensive player in league history.

* * *

Tom Brady isn’t giving up, yet

When Patriots quarterback Tom Brady announced on Facebook that he “made the difficult decision to no longer proceed with the legal process,” the logical conclusion was that he had opted not to file an appeal of his Deflategate suspension with the U.S. Supreme Court.

Then came this caveat from the NFL Players Association: “We will continue to review all of our options and we reserve our rights to petition for [appeal] to the Supreme Court.”

The appeal can’t go forward without Brady; if Brady truly wants it to be over, there will be no further appeal. The reality is that Brady has (per a source with knowledge of the situation) authorized the NFLPA to proceed with the appeal on his behalf. It won’t keep him from missing the first four games of the season, but it could ultimately restore his lost pay of more than $253,000, reduce the Commissioner’s power in player disciplinary cases, and provide Brady with genuine vindication.

There’s also a pretty good chance he’ll return after Week 4 with a chip on his shoulder the size of a car battery and a primal scream or two powerful enough to start the car where the battery was removed. Regardless, the idea that Brady has pulled the plug completely isn’t accurate. The suspension will be served, but the fight most likely will continue.

* * *

Quotes of the Week

I

“I will pull Cleveland officers, sheriffs, state troopers out of FirstEnergy Stadium this season if he doesn’t make it right. You’re a grown-ass man, and you claim you were too emotional to know it was wrong? Think we’ll accept your apology? Kiss my ass.”

—Cleveland Police Patrolman’s Association president Stephen Loomis after Browns running back Isaiah Crowell issued a simple apology for posting on social media a disturbing image of a police officer having his throat slashed. Crowell later pledged his first game check of the season, worth $35,294, to the Dallas Fallen Officer Foundation. Loomis accepted the gesture and rescinded the boycott.

II

“The word of the week has tended to be acrimonious. I think we all wanted to make sure there was no acrimony or animosity from this point moving forward. What happened in the past couple of days is in the past couple of days. And it frankly doesn’t matter going forward.”

—Ravens kicker Justin Tucker, a day after his agent said Tucker had grown disillusioned with the process of negotiating a long-term deal and vowed not to re-sign with the Ravens if a new contract wasn’t worked out before Friday’s deadline.

Clearly, $10.8 million in guaranteed money for a kicker who would have made $9.9 million over the next two years under the franchise tag goes a long way toward unruffling feathers.

III

“I don’t ever want to say I’m giving up, because that’s never going to be me. ... I know that the window for playing is closing.”

—Former Ravens running back Ray Rice, who has been ostracized by the NFL since the notorious elevator video emerged in September 2014.

From the glut of players at the position he plays to his subpar performances in 2013 to the baggage he’d bring to a locker room, the window isn’t closing. It was nailed shut months ago.

IV

“As an organization, we are disappointed that Karlos has put himself in this situation. Poor decisions as this affect not only the individual, but the entire Bills organization. We will continue to work with Karlos through the various player programs we provide to assist him in making better decisions moving forward.”

—The Buffalo Bills upon announcing that second-year running back Karlos Williams has been suspended four games for violating the league’s substance-abuse policy.

A four-game suspension typically comes after multiple failed tests, which means that the team’s “various player programs” have to date failed. If that continues, he’ll potentially be suspended 10 games for his next violation and then banished from the league for at least one calendar year.

V

[Silence.]

—The Tampa Bay Buccaneers after Miko Grimes, the wife of cornerback Brent Grimes, made an anti-Semitic remark regarding Dolphins owner Stephen Ross and executive V.P. of football operations Mike Tannenbaum. The Buccaneers, owned by a Jewish family, had no comment regarding the situation.

On one hand, the Bucs knew what they were getting when they signed Grimes, given his wife’s history of outlandish statements. On the other hand, the moment the Buccaneers believe they can replace Grimes with someone younger and cheaper, their silence likely will end with a one-sentence press release that officially ends the relationship.

* * *

Stats of the Week

Since entering the NFL as a rookie first-round pick in 2011, Broncos linebacker Von Miller has 60 sacks. Since entering the NFL as a rookie first-round pick that same year, Texans defensive end J.J. Watt has 74.5 sacks.

Watt has played in all 80 career regular-season games, giving him 0.93 sacks per game. Miller has missed eight, so his average sits at 0.83 sacks per game. Watt’s career postseason average is even better, with five sacks in five postseason games.

Miller racked up a total of five sacks when it mattered most, with 2.5 against the Patriots in the AFC title game and another 2.5 in Super Bowl 50 against the Panthers. Those back-to-back performances helped Miller cash in, but it’s hard not to think that Watt is underpaid in relation to Miller, making $16.67 million per year in comparison to Miller, who is at $19 million annually.

Here’s the real difference between their contracts. The Texans gave Watt his current deal before the 2014 season, allowing him to trade in the back end of his rookie contract and shift the injury risk for 2014 and 2015 to the Texans. If Miller had gotten the same offer from the Broncos in 2014, he surely would have taken it.

And if Watt had never been given a long-term deal, he would have gotten something along the lines of $19 million per year after his rookie contract expired.

Meanwhile, the player taken five spots after Miller and four before Watt at one point seemed on track to be the best of the three. Former 49ers linebacker Aldon Smith had 33.5 sacks in his first 32 games, an average of 1.04 per game. After his third season, which featured 8.5 sacks in 11 games, the average was still at 0.976 per game.

But for an inability to stay out of trouble, Smith currently could be making as much or more than Miller or Watt. Smith, now with the Raiders, remains suspended by the league, with the ability to apply for reinstatement in November.

* * *

Factoid of the Week That May Interest Only Me

This season, the Detroit Lions will honor the 1991 edition of the team, the last one to win a playoff game. That year, the Lions made it to the NFC title game against Washington, which won the Super Bowl.

The Cowboys won three of the next four Super Bowls. Since then—a full 20 years ago—Detroit, Washington, and Dallas are the only three NFC teams to not play in the conference championship game at least once.

* * *

Mr. Starwood Preferred Member Travel Note of the Week

I work at home, so in the offseason I rarely travel. I do have to walk from the bedroom to my office, and on Tuesday I was still a little drowsy when I got there.

* * *

Tweets of the Week

I

Love Marky Mark (good vibrations is a classic) but this call from @nflcommish never happened @Deadspin https://t.co/ukALTsGAOM

— Natalie Ravitz (@Nravitz) July 17, 2016

After completely ignoring the existence of HBO’s Ballers, which uses NFL team names and logos without permission and puts players in a Playmakers-style light, and after declining comment regarding executive producer Mark Wahlberg’s claim Friday that Roger Goodell personally called with a plea to scrap the show, the league’s new senior V.P. of communications issued this and several other tweets on Sunday disputing Wahlberg’s contention.

II

FOR LIFE pic.twitter.com/ayvzpJ1WZh

— Von Miller (@VonMiller) July 15, 2016

“For life” only means “for life” if the Broncos think they’re still getting a good deal once the guaranteed money expires, which is why the issue of guaranteed money was so important to the deal.

III

Very well deserved. Congrats @Millerlite40!

— JJ Watt (@JJWatt) July 15, 2016

At least he didn’t include a photo of himself wearing a Von Miller jersey five sizes too small.

IV

Just did. https://t.co/hm3gWpKhmM

— New York Jets (@nyjets) July 15, 2016

The Jets pulled off one of the all-time franchise-tag stunners by signing Wilkerson, a player about whom they had seemed ambivalent for years.

V

Yea that cause the cba y'all voted for gave him the power to dish out any punishment he wants! #steelersvotedno https://t.co/lRZKah07Bd

— James Harrison (@jharrison9292) July 13, 2016

The Steelers were indeed the only team that voted against the current labor deal. It’s one thing to be a contrarian when the outcome isn’t going to change, it’s quite another to stick to that position if it means surrendering up to a full year of wages. It’s hard to imagine the Steelers players would have been willing to do that in 2011.

* * *

Ten Things I Think I Think

1. I think officials privately have been told to call a catch a catch if they think it’s a catch, and not to worry about the convoluted language of the rule regarding players who are going to the ground, which has gotten even more complex this year. I think this year’s changes to the rules are intended to make it even harder to overturn via replay review a ruling on the field of a catch, given the very high standard of indisputable visual evidence. And I think the NFL won’t be admitting any of this because it will make the Dez Bryant non-catch from the 2014 playoffs even more glaring. Ultimately, I think this is an acceptable way to ensure that future calls mesh with the expectations of players, coaches, owners, fans, and media regarding what is and isn’t a catch.

2. I think I don’t know what to think about whether the excellent NFL Films series “All or Nothing,” featuring the Arizona Cardinals, is or isn’t a hit. An Amazon spokesperson told me the company doesn’t release streaming figures, so it’s impossible to know how many people have watched any, some or all of it. I think I also don’t know the whole story about the 2015 Cardinals, because only eight of 1,000 hours of footage made it to the final cut. The team and the league showed us only what they wanted us to see, which makes me really want to see the stuff they didn’t want us to see.

3. I think the NFL would get rid of the kickoff today if it could come up with a comparable procedure for transferring possession while also giving the kicking team a slim chance of retaining possession. In a 2012 Time magazine profile, Commissioner Roger Goodell floated the idea of giving the kicking team the ball at its own 30, facing fourth down and 15. The “kicking” team could then punt the ball (the new kickoff), go for it from a normal offensive set (the new expected onside kick), or run a fake punt (the new surprise onside kick). The idea never got any real traction. The latest effort to reduce kickoffs entails moving the touchback (as a one-year experiment) to the 25, which invites the possibility that more kickoff returns will happen if teams deliberately kill the ball short in an effort to pin the opponent inside its 25. If this approach doesn’t work, don’t be surprised if fourth-and-15-from-the-30 or some other idea for replacing the kickoff in a meaningful way emerges.

4. I think it’s smart for the Giants, as receiver Dwayne Harris told the team’s website, to work on throwing more deep passes. Bengals coach Marvin Lewis previously told first-year Bucs coach Dirk Koetter that offenses don’t throw deep enough, and first-year Giants coach Ben McAdoo has apparently gotten the message. Throwing deep amounts to a reduced-risk, enhanced-reward move, carrying the added benefit of forcing the defense to account for the long ball and, in turn, opening up the short and intermediate passing game.

5. I think quarterback Aaron Rodgers, who said this week on HBO’s “Any Given Wednesday” that he hopes to retire with the Packers, probably will do so only if the team wants it to happen. If Rodgers intends to play beyond the point where the Packers still want him, Rodgers would have to follow in the footsteps of Brett Favre and go elsewhere. Free agency and the salary cap, which were created to give veteran players mobility, routinely have forced teams to move on from key players years before that would have happened in the days before free agency, when the expiration of a player’s current contract meant that he either signed a new one with the same team or found something else to do for a living.

6. I think I’m a little excited to see U.S. Bank Stadium, the soon-to-be-opened home of the Vikings. I’ll be broadcasting PFT Live on NBC Sports Radio from there on Thursday and maybe Friday, the day they officially open the replacement for the Metrodome. As tight end Kyle Rudolph recently told SiriusXM NFL Radio, all that matters is whether the team wins there. Based on quarterback Teddy Bridgewater’s strong performances when playing road games in domed stadiums during his first two NFL seasons (the Vikings played their 2014 and 2015 games outdoors at the University of Minnesota), the Vikings are optimistic that Bridgewater will play better at home. And I think the clearest test regarding whether Bridgewater will thrive will come from what extent the Vikings use offensive coordinator Norv Turner's “Bang 8” route with rookie receiver Laquon Treadwell. Matt Vensel of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune explained over the weekend how the staple of Turner’s offense more than 20 years ago with the Cowboys could resurface in Minnesota. Michael Irvin, the Bang 8 target in Dallas who routinely ran the skinny post and took some thick hits in the process, believes Treadwell can fulfill his part of it. But it won’t work unless Bridgewater can consistently put the ball in a spot that keeps Treadwell from becoming too much of a sitting duck for safeties who will be waiting to greet the rookie when he angles inside to make the catch.

7. I think with all the violent and awful things going on throughout the world, high-profile NFL players should be a little more careful when traveling abroad. The sounds and images of Giants receiver Odell Beckham Jr. climbing onto a car to selfie-capture an “O-B-J”-chanting crowd in Germany were as entertaining as they were frightening. At a time when Americans are natural targets when they cross either of the oceans that border the country, high-profile American athletes become even more attractive for those who want to disrupt our way of life by creating as much havoc and mayhem as possible.

8. I think the NFL should commit to disclosing the compensation given to the commissioner and other highly-paid executives despite the change in league-office tax structure that eliminates the legal obligation to do so. Player salaries are known; the commissioner’s should be, too. The information can now be hidden because foes of the NFL continuously tried to paint the league as a tax evader by pointing to the non-profit status of the league office. It was a dumb argument; the league passed revenue through to the individual teams, which paid their own taxes separately. The league finally reacted to the disingenuous attacks by giving up the broader tax-exempt status and, in turn, slamming the door on public availability of how much the commissioner makes.

9. I think the Jets have sent a clear message to every agent regarding the team approach to negotiating contracts. Identify the deadline, do nothing until the eve of it, and then fire up the midnight oil. The Jets showed no interest in signing franchise-tagged defensive lineman Muhammad Wilkerson to a long-term deal until roughly a week before the window was due to close. An impasse over length quickly derailed the discussions until literally the night before the clock struck 4 p.m. ET. The Jets then applied pedal to metal until Wilkerson was ready to apply pen to paper. So now the agent community knows how the Jets do business. More specifically, now agent Jimmy Sexton will know to leave his phone on when he goes to bed the night before the Jets open training camp, because that's the practical deadline for getting quarterback Ryan Fitzpatrick back in the fold.

10. It think these are my non-football thoughts of the week...

a. Growing up in the ’70s, I remember times where the world seemed like it was turned upside own. It feels like that again, and the only solution that works for me is to keep doing what I do and hope it helps create a temporary distraction for football fans from much more important issues.

b. Regardless of anyone’s political beliefs, we all should be a little troubled by the article in The New Yorker from George Saunders detailing the face-to-face squabbles of those who support and those who oppose Donald Trump’s presidential run. The red state/blue state divide that first emerged in the 2000 election has become a red country/blue country, with citizens of the two distinct nations living elbow to elbow and, on matters of politics, speaking entirely different languages fueled by the narrow echo chambers from which each side gathers its information and sharpens its opinions. Caught in the middle are those who have grown so weary with the complete lack of common ground and civil discourse that, eventually, apathy will take root.

c. For anyone who is interested in learning how to play the guitar, there’s nothing more fun or effective than the Rocksmith video game. I took lessons when I was a kid, I got frustrated after a couple of years because I wasn’t learning how to play like Ace Frehley, and I went 35 years without touching a guitar. Rocksmith is Guitar Hero with a real guitar, starting out with simple plucking and strumming that gets harder with improvement. It’s addictive, it’s rewarding, and I’m going to have to find a way to carve out time to play it once training camps open and the regular season begins. It’s also nice to actually have a hobby for the first time since my hobby became my career.

d. With all the talk about how much NBA and MLB players get paid in relation to NFL players, one set of athletes deserve much more money for what they do: Hockey players. The controlled chaos entails Rollerball-style hazards, from razor-sharp blades to long wooden sticks to a hard rubber missile that gets a lot harder and a lot less rubbery when it’s frozen and flying in the direction of someone’s face. The players skate with precision, jostle at full speed, bang into wooden boards, get exhausted quickly and then come back and do it again after a short rest, playing up to 110 60-minute (or longer) games per year. Unfortunately, players salaries in all sports are driven by revenues, and hockey still hasn’t found the national following it deserves.

e. We tend to dislike athletes who talk too much, but the ones who say little or nothing often get lost in the shuffle. Retired San Antonio Spurs star Tim Duncan won’t get the widespread credit he should for winning five NBA titles, three NBA Finals MVP trophies, a pair of league MVP awards, and earning 15 All-Star appearances because he went about his business and didn’t draw any extra attention to himself. He retired the same way he played, with no fanfare or effort to highjack the spotlight.

f. We still apply a bizarre double standard to doping. When baseball players get caught, eyebrows raise and fingers point. When football players or, more recently, a rash of UFC fighters test positive, we shrug with the assumption that guys don’t get that big or strong or fast or durable without some sort of pharmaceutical help. That’s not fair to the athletes in both sports who are clean.

g. If you’re 50 or older and have never had a colonoscopy, get one. Not for yourself, but for those who count on you being, you know, alive. Colon cancer not only can be caught early but also can be prevented if a polyp is found and removed before it becomes a malignancy. It’s a far easier process than believed, and it’s far better than the alternative. However, and as the person for whom I’m subbing would tell you, do not commence the preparation process while flying home from a Pro Day workout in Texas.

h. The Olympics always amaze me. Sports that we care little (if at all) about for three years and 50 weeks suddenly become the most important sporting events in the world, in large part because the outcomes are tied directly to national pride. People most of us have never heard of will skyrocket to household-name status faster than the most rare and elusive critters in Pokemon Go. And then, after the Closing Ceremonies, we’ll forget about most of the sports played during the Games for the next three years and 50 weeks.

i. Football should be an Olympic sport. (I know these are supposed to be non-football thoughts. I really don’t have very many non-football thoughts.) But it shouldn’t be part of the Summer Games. Football should be an event in the Winter Olympics, played on snow deep enough to flatten out the talent gap between American players and everyone else.

j. How about this compromise? Combine football with some form of skiing or skating or snowboarding and make it an event in the Winter Olympics. I mean, cross-country skiing and shooting guns is a thing.

k. Call me a company man if you want, but I’ve never understood the complaints about NBC showing Olympic events on a delayed basis. For people who want to see the events live, there’s a way to do it. NBC pays what it does for rights to televise the Olympics in order to have two-plus weeks of prime-time programming, where the audiences remain at their largest. Unless and until people stop clustering around TVs during the evening hours to watch taped events on NBC, why should that approach change?

m. I’m definitely a company man when it comes to the company founded 15 years ago in my basement. (It wasn’t really founded in my basement, although that sounds better than the truth.) And I appreciate every day the guys who work hard nearly every day to put content at ProFootballTalk.com: Michael David Smith, Darin Gantt, Josh Alper, Zac Jackson, and Curtis Crabtree. (Now that I’ve sucked up, guys, get back to work.)

n. I’m also a company man when it comes to NBC Sports Radio, where PFT Live has had a home since January 2015. From 6 to 9 a.m. ET every weekday (with a re-air from 9 to noon), Rob “Stats” Guerrera and I break down the NFL news of the preceding day and set (or at least try to set) the agenda for the coming day. On the agenda for the weeks following the Olympics: A two-hour daily simulcast of the show on NBCSN, from 7 to 9 a.m. ET, leading in to The Dan Patrick Show. Matt Casey will run the operation; he and Stats came to my house in West Virginia for a planning session last month, and they both have some excellent ideas for making the show as good as it can be on both radio and on TV. Kristen Coleman will direct traffic, which probably will be the hardest job on the show given my tendency to stray from the point.

o. Speaking of Dan Patrick, there’s no way I’d be doing a three-hour daily radio show if he hadn’t given me a chance to sit in for him, which happened the first time six years ago. I had no training and no experience and no idea what I was doing (and it showed). But with help on the radio side from guys like Jonas Knox on the radio side and Paul Pabst, Seton O’Connor, Todd Fritz, and Andrew Perloff on the TV side, I managed to bluff my way through the radio game until I kind of began to figure it out. I’m grateful to all of them for their help along the way—even if I don’t feel very grateful when the alarm starts blaring at 5 a.m. and I was up until 1 a.m.

p. Speaking of substituting for things, thanks to Peter King for risking the sullying of his otherwise fine reputation (that seems sarcastic but it’s not) by inviting me to fill his seat for the last Monday before he returns from vacation. For the past six years, I’ve seen him working and working and working on this column every Sunday during football season, but I still didn’t realize what it really entailed until I started writing it. He does this nearly every Monday, with more than 20 of them being feverishly cobbled together on the fly as he digests the storylines of every given Sunday. Peter, if you ever ask me to do this again, I won’t say “thank you;” instead, my answer will still consist of two words and will also end in “you.”

q. While watching regular-season games on Sundays at NBC, I have Rodney Harrison on my left and Peter on my right. At least five times per Sunday, Rodney spontaneously shouts “oooooh!” in response to a hit in one of the games on the Brady Bunch wall in front of us and Peter inevitably cries out, “Who? What? Where?”

r. Peter and I work on opposite ends of the same large table during the second half of the late afternoon games, NBC’s Football Night in America, and Sunday Night Football. Over the years, the top Seinfeld lines that routinely make the way into our otherwise high-level football discussions (now that should seem sarcastic) are, in no particular order: 1. “Cartwright!”; 2. “Was that wrong?”; and 3. “He took it out.”

r. Coffeenerdness: I drink whatever coffee is put in front of me, as long as it’s hot. One of these days, I’m going to get a thermometer and then through a series of tests I will determine the specific point at which hot coffee goes from being drinkable to swill. Which literally would be coffeenerdness.

s. Beernerdness: I drink whatever beer is put in front of me, as long as it’s cold. One of these days, I’m going to get a thermometer and then through a series of tests I will determine the specific point at which cold beer goes from being drinkable to swill. Which literally would be beernerdness.

* * *

The Adieu Haiku

Terry Bradshaw lives.

But my own tombstone will say

I once said he died.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.