More Money, More Problems

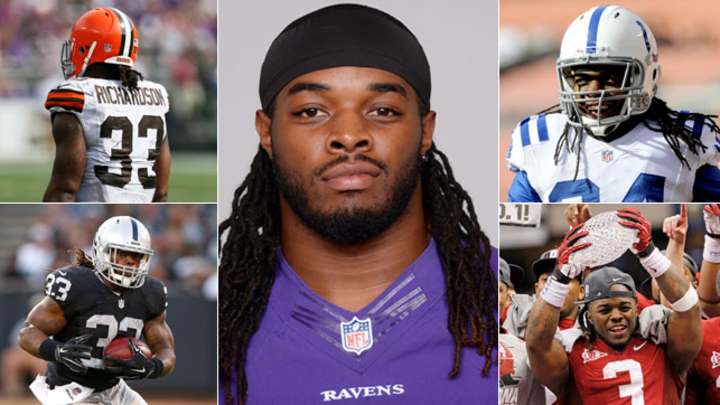

Trent Richardson arrived in the NFL with great pedigree, a two-time national champion drafted out of Alabama in 2012 as the third overall pick. He was the highest-selected running back since Reggie Bush six years earlier, and signed a fully guaranteed four-year, $20.4 million contract, which included a $13.3 million signing bonus. Even a year later, when he was traded to the Colts for a first-round pick, his stock was still high. The overwhelming sentiment was that the Colts had clearly won that trade.

Richardson, of course, lasted two seasons in Indianapolis. He wound up in Oakland last season, and was picked up by the Ravens this offseason, only to be cut earlier this month. Now an NFL career that began with so much promise appears to be, at best, hanging on by a thread.

Human ATM

Richardson was the focus of a recent segment on ESPN’s E:60 that caught my attention and brought back a lot of memories, especially from the chapter of my life as an agent. Richardson discussed the financial pressures from friends, assorted family members and hangers-on—pressures that took his focus away from where it should have been. He detailed 10 people living in his house and losing approximately $1.6 million of his money in a 10-month stretch between January and October 2015 (when continued football earnings were far from secure); he was faced with requests to pay rents, car payments, and even to prevent a house from being repossessed.

• INSIDE THE MONEY: Catch up on all of Andrew Brandt’s Business of Football columns

These kind of stories—in recent years, players such as former Raiders’ top pick Phillip Buchanon and Cowboys’ tackle Tyron Smith come to mind—often draw skeptical reactions from the public; people wonder why a player cannot control spending money on those around him. And while there is certainly more Richardson could have done to stem the flow, I empathize having seen these situations firsthand as both an agent and a team executive.

The Herd

One of the more common misconceptions about player management is that an agent (or team executive) only deals with the player. Agents appreciate dealing with a player who only has a wife/girlfriend/parent involved in his business; those cases, however, are exceptions. Most often, an agent must deal with what I call “the herd” when taking on a player, which can include (but is not limited to) parents, siblings, cousins, advisors, friends, wives, girlfriends, and wives and girlfriends.

While it is hopeful to think that their intentions are always in the best interest of the player, they are often in the best interests of themselves. And if the player does not support family or friends, financially and emotionally, he is often seen as turning his back on his past. I have seen it many times: people around the player can have a financial and emotional strain that can affect on-field performance.

“He’s family”

As an agent, I once represented a player who had a much older half-brother who was a smooth talker with big plans to represent musical artists and build a record company using, of course, my client’s money. However, besides being an engaging salesman, he had addiction issues. The brother had asked my client (and me) for relatively small amounts of money—usually $2,500 to $5,000—that, even with my skeptical counsel, my client willingly gave to him. This led to the big “ask” when he approached my client with the record company idea and requested $100,000.

I stepped in immediately to say no and my client did the same, to which the brother backed down, but only for a while. He was soon back, finally wearing down my client who agreed to write the check. I was livid. Not knowing to whom I could vent, I wrote a letter to my file expressing my opposition, a letter I still have. My client just threw up his hands and said two words to shut me up: “He’s family.” (The record company never materialized.)

“What do you do?”

I also had a difficult experience dealing with a herd member—a player’s friend from childhood—when I was with the Packers’ front office.

We had a young player with great potential who had moved up to Green Bay with his close friend. Although the player was constantly getting into some scrapes with the law, there was always a pattern: the friend, not our player, was the instigator.

I first tried working through the player’s agent, who knew of the situation but had no success in having the player separate from his longtime friend; the player was adamant about not turning his back on him. The one time I mentioned it to the player, he simply responded, “He’s my guy. And there’s no black people living up here.” Once it finally reached the point where coaches and players were questioning the friend’s influence, I decided to step in, with the agent’s blessing.

I approached the friend in the reception area after the game, brought him to my office and asked directly: “It’s great that you are here for our player, but what exactly do you do?

“Excuse me?” the friend said.

“What do you do all day?”

“Make sure my guy’s s--- is right.”

“What does that mean?”

“You know, pick up things for him, get the car washed, that stuff.”

“OK. And you guys go out a lot, right?”

“We hang out, yeah.”

“Here’s the problem,” I said. “We have big plans for him, but he can’t live the same schedule that you do. He needs to rest and recover.”

“We only hang out, say, three or four nights a week.”

“That’s too many. How about one?”

“Hmm. Two or three?”

“One.”

The player slowly gravitated more to teammates and, halfway through his second year in the league, the friend left Green Bay for good. Not surprisingly, the player’s performance greatly improved.

I share these personal experiences not to absolve Richardson of being a major disappointment on the field, but to expose more pressures on players than what meets the public eye. Family and friends draining players’ financial (and emotional) resources can be wearing. And while we would like to think that players should be able to compartmentalize and not let it affect their performance, it is often not that easy.

Richardson’s situation is a cautionary tale for many athletes. Though it sounds easy, it is actually hard—but necessary—to just say no, even to family.

Five Thoughts About the NFL’s Ultimatum

Clay Matthews, Julius Peppers, James Harrison and Mike Neal have been threatened with indefinite suspensions if they fail to cooperate with the league’s investigation over PED allegations made in the Al-Jazeera report that also implicated Peyton Manning, who met with the NFL and was cleared of any wrongdoing.

The deadline for speaking with league investigators has been set for Aug. 25.

1) Just as Deflategate moved way past being about deflated footballs, this is about more than alleged PED use (which, by the way, the league has a system in place to test players for). Emboldened by two Circuit Court of Appeals rulings regarding Tom Brady and Adrian Peterson, the NFL now seems to move a PED allegation—with established CBA discipline—into the player conduct realm, the Conduct Commissioner's cherished space.

2) The NFL doesn't react well to hearing the word no—especially from the NFLPA. The union provided what the NFL called “cursory statements” and then stonewalled the league’s inquiry. The NFL also appears to be saying to the NFLPA that they will determine guilt or innocence, not vice versa.

3) There were reports that the players would speak to investigators earlier this summer; the reports were either wrong or the players changed their minds. It could also mean that the players and/or their agents want to talk but the union—in the interests of establishing precedent for all players—does not want to let them. We saw this internal battle between agent and union last year regarding Tom Brady’s strategy in the investigative process.

4) Once again, we are back to where we started: the CBA-endorsed commissioner power over player conduct, a domain that seems to have gotten stronger, not weaker, after years of NFLPA litigation. The owners are now in prime negotiating position to leverage even more gains in the next CBA should the players decide to make this an issue (which they shouldn’t).

5) As I say often, we have a 10-year labor agreement, but we have never had labor peace. NFL and NFLPA leadership not only don’t trust each other, they also don’t appear to like each other. One can only wonder if the NFL and NFLPA would fight each other so hard on everything if there were some kind of relationship between Roger Goodell and DeMaurice Smith. They certainly don’t need to be friends; they just need to not be such bitter enemies.

Question? Comment? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com