Colin Kaepernick Stands Up By Sitting Down for Anthem

Colin Kaepernick’s decision to sit for the national anthem in protest of institutional racism in America—an unprecedented move in the vast non-partisan tradition of quarterback behavior—made me think of the fall of 2012, when I had a unique glimpse into the world that raised Colin Kaepernick.

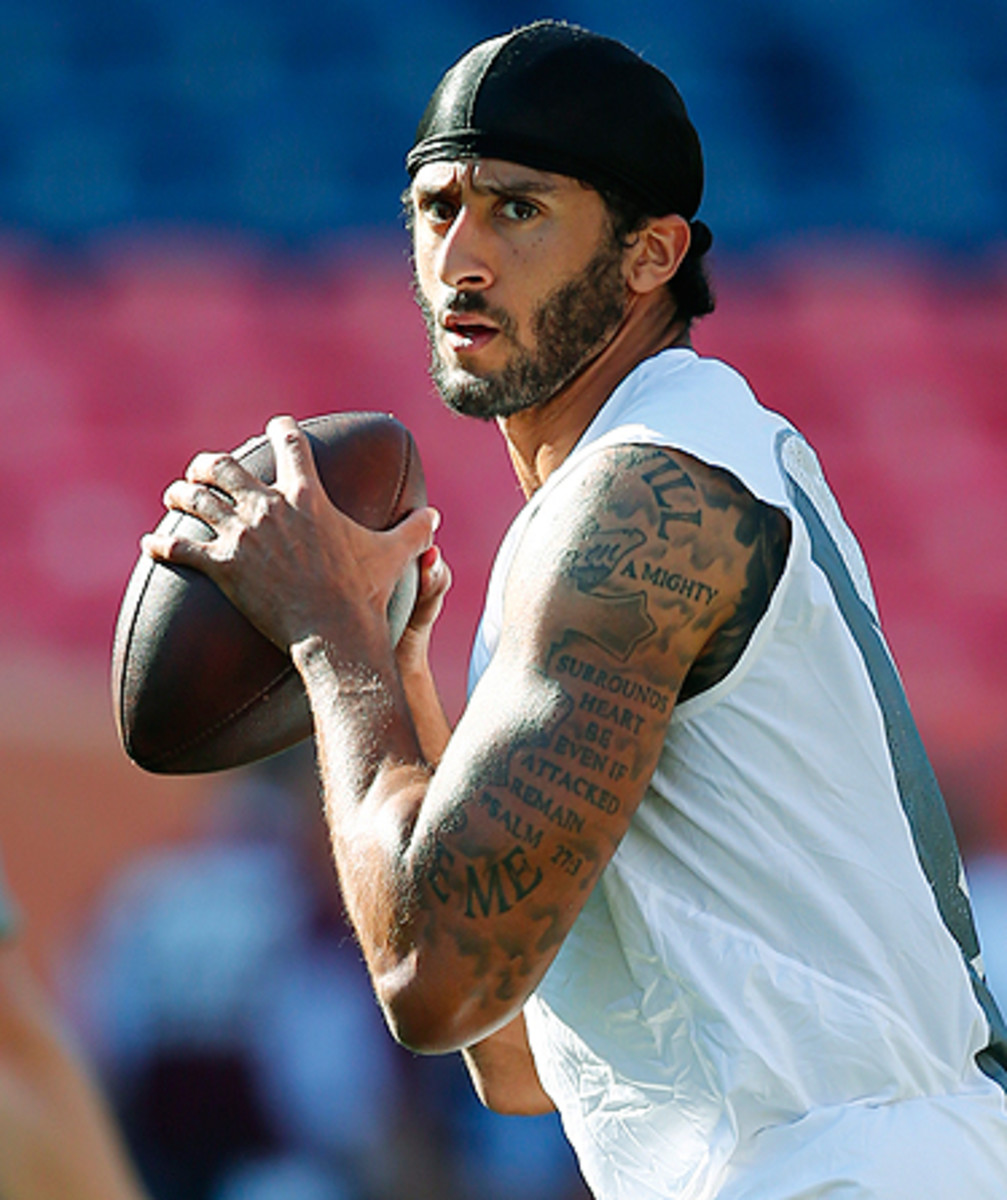

I was a rookie reporter at USA Today at the time, two years removed from college, and the same age as Kaepernick. USA Today’s NFL editor Kevin Manahan sent me to Turlock, Calif., to profile the quarterback who had just taken the starting job in San Francisco from longtime starter Alex Smith. Kaepernick was big, fast, soft-spoken, and he lit up the NFL that season. He also was black and covered in tattoos, two facts which became a big part of the storyline the day I arrived in his sleepy hometown of 70,000 nestled between Modesto and Merced in NorCal farm country.

On Nov. 28, 2012, the Sporting News published a column by David Whitley criticizing Kaepernick for the example he was setting as a quarterback covered in ink. Wrote Whitley: “NFL quarterback is the ultimate position of influence and responsibility. He is the CEO of a high-profile organization, and you don’t want your CEO to look like he just got paroled.”

• NINERS CAMP REPORT: Peter King on Blaine Gabbert, Chip Kelly, more

He went on to draw comparisons to other tattooed quarterbacks of note: “Then there are Michael Vick and Terrelle Pryor. Neither exactly fit the CEO image, unless your CEO has done a stretch in Leavenworth or has gotten Ohio State on probation over free tattoos.”

The Internet rose up and smothered Whitley in the manner we’ve become so familiar in the years since. Readers noted racial undertones in Whitley’s work. I wondered what Kaepernick thought about it, but he wasn’t saying. The 49ers weren’t making Colin available to individual reporters for the most part that fall; his celebrity was white-hot, and he was just a bit unsure of himself. But I had free rein to ask his parents, Teresa and Rick, whatever I wanted.

I knew their reaction would be newsworthy if they took any sort of stance, but I wanted to go deeper into issues of racial identity. Colin, after all, was adopted by white parents as an infant and never had any sort of relationship with his black father. Had his parents raised him to identify as a black man living in the all-white enclave of Turlock, or simply as a citizen of the world?

I got my answer in the Kaepernick living room.

“When we adopted him, I bought some books from the library on raising children from another race, but what it all came down to was common sense more than anything,” Teresa said then. “You want him to feel really good about the race he is. You’re not trying to make him white.”

In junior high school, Teresa drove Colin an hour to Modesto to have his hair corn-rowed like Allen Iverson. From the beginning, they taught him to embrace his heritage.

“I remember very well, he was just a couple years old, him putting his arm next to mine and saying, ‘Look, I’m brown! How come I’m brown?’” Teresa recalled. “And I said, ‘Yeah, that’s not fair, you’ve got that pretty brown color, and look at me, Mom looks like paste! You look great.’ And he would just beam.”

You can disagree with how the Kaepernicks raised Colin; plenty people surely do. But what the Kaepernicks recognized early was the folly of raising a black man in America to believe he was anything other than black. Perhaps then, he might be emotionally prepared years later when white columnists compare him to inmates despite his squeaky clean police record and extensive charitable contributions.

By the same token, that child might grow up and decide he’d seen enough extrajudicial police killings of African Americans at a disproportionate rate, heard enough campaign rhetoric painting blacks as helpless and downtrodden and minorities as violent criminals, and learned enough about how America prefers its black athletes to shut up and appreciate the spoils of their hard work, to take a stand. Even then, armed with that perspective of the world, that stand was unlikely.

Quarterbacks just don’t speak out on social issues. Like Whitley said, they’re the CEOs, and CEOs in NFL locker rooms aren’t meant to be black or white; their job is to bring in the green. In comments to NFL.com’s Steve Wyche explaining his actions, Kaepernick acknowledged he’d put his professional future at risk in deciding to protest the anthem.

“This is not something that I am going to run by anybody,” he told Wyche. “I am not looking for approval. I have to stand up for people that are oppressed. ... If they take football away, my endorsements from me, I know that I stood up for what is right.”

In the end, for the kid from Turlock, the words and guidance from his parents who so prepared him for life in the spotlight as a black athlete, compelled him to risk his livelihood for what he believed was the truth—that a country which calls itself free has a great deal of unimpeded racial inequality.

Francis Scott Key wrote about the land that breeds this sort of citizen: The home of the brave.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.