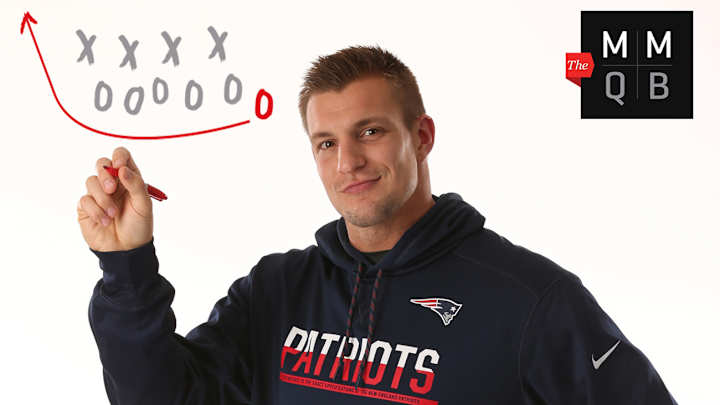

Rob Gronkowski, Football Mastermind

Editor’s Note: Peter King and the staff of The MMQB took over this week’s issue of Sports Illustrated magazine. In it, you’ll read the kind of feature stories like this one that you’ve come to expect from The MMQB, plus an all-access behind-the-scenes look at one day in the life of the NFL, from inside the Texans’ team meeting on the night before the season opener to the Patriots’ celebrations at the end of their surprise win in Arizona, and much more. Pick up the magazine on newsstands, or subscribe here.

* * *

Let’s start with a disclaimer. This is a story about Rob Gronkowski: Tight End, not to be confused with the celebrity known as Gronk. Over the following pages you will find no partying. No shirt removals. No dancing, twerking or flexing. There will not be a single scene set inside a club, at a beach or on a pool deck. No Instagram photos whatsoever. In fact, for this story, Rob Gronkowski is sitting in a dinky break room in the bowels of Gillette Stadium. And he’s talking football. Only football.

We’re not here because Gronkowski is the NFL’s best tight end. (He is.) We’re here because he just might be the smartest.

Skeptical? Then consider Bill Belichick’s take:

“The tight end position is, probably after quarterback, the hardest position to play in our offense. That’s the guy who does all the formationing. The running back is usually in the backfield. The receivers are receivers. But the tight ends could be in their tight end location, they could be in the backfield, they could be flexed. They could be in the wide position. To formation the defense, those are the guys you’re going to move. It’s moving the tight ends that changes the defensive deployment.”

Practice is about to begin at Gillette, but Belichick is volunteering more information on Gronkowski. In fact, he’s expansive, even congenial.

“Rob is a versatile athlete, but he’s also a versatile guy mentally. He can handle a lot of different assignments. Some guys can’t. Either they mentally can’t do it, or it’s just too much and their game slows down. They don’t play to the same skill set you see athletically because they’re thinking too much. That’s not the case with Rob.”

And with that, we introduce you to a player you’ve seen but never truly known: Rob Gronkowski, Football Mastermind.

* * *

In that Gillette break room (a month before a hamstring injury forced him out of the Patriots’ Week 1 win over the Cardinals), Gronkowski sits at a table with nothing in hand. He’s in a bright blue T-shirt and shorts. He makes steady eye contact, leaning back when listening to a question and leaning forward when answering it. The more directly the topic is football, the more easily the conversation flows. The focus of the discussion is his versatility.

Gronkowski has seen significant playing time at four positions for the Patriots (chart): traditional tight end, slot receiver, wide receiver and X-iso receiver (where he’s split out alone on the weak side). And don’t be surprised if this season he lines up in the backfield at times. This flexibility is what Belichick means by “formationing.” As Belichick explains, “There are a lot of defensive looks that go with that formationing. If you’re always in the same spot, you’re probably going to see only a few different looks. When you’re in a lot of different spots, the look changes. Different assignments. Different techniques. A different picture on the defense. And as those multiples go together, it just becomes exponential. Three different plays become 15 plays.”

Gronkowski gets it. “Many, many times you have to be a football mind,” he says. “I’ve seen a lot of athletic juggernauts throughout high school, college, even the NFL who can’t play the game. When you first get [to the league], it’s learning a whole new language. You have to learn the playbook inside and out. You have to learn code words for each play. You have to learn defenses. You have to just have football knowledge. Without football knowledge, it doesn’t matter how much skill you have.”

A player is asked to do a litany of things only if he can do them well. Coaches and teammates marvel at Gronkowski’s diverse attention to detail. In particular, getting open has become a science for him.

“When I first got into the league, I just used to run,” Gronkowski says. “Just run the route. Really no technique to it. I really couldn’t separate myself from the defender. I just listened to my coaches, went through the cone drills and everything.” That, of course, was not good enough for the future Hall of Famer throwing him the ball.

“Tom [Brady] is a teacher,” Gronkowski says. “At first he just tells you what to do. If you don’t get it right after that, he’ll come at you hard. He’d come at you really hard back in the day. He’s not really like that anymore, at age 39. But back in the day, like six years ago, he used to come at me hard if I didn’t do it right.”

One particularly brutal practice from his rookie season, now six years ago, still sticks with Gronkowski. “Tom wanted me to get outside leverage on this flag route, and I just couldn’t. I just kept going inside. And he just flipped out on me about it. He said, ‘All right, the ball’s not going to you then.’ ” Gronkowski’s eyes drift down as he relates the story. “I remember that.” After a slight pause, he says, “So finally I just started learning, All right, I’ve got to get outside.”

Brady stopped hounding the young tight end after he learned that route running is “all about little techniques,” Gronkowski says. “Having defenders think you’re going somewhere else. And always remembering to run what looks like the same route as before, but boom: At the top you stick it off one way or you stick it off the other. But all the way to the top of the route, it looks the same. I’ve worked on that a lot throughout my career.”

Like a chemistry professor going through the periodic table, Gronkowski expounds on his varied positions, detailing the nuances of each branch on the route tree. Perhaps the biggest factor behind his success in New England’s voluminous, multifaceted offense has been “learning how to read the safeties. There are a lot of routes, about five or six in the playbook, where if it’s split-high

, I have to run one certain route, and if it’s single-high [one safety deep], I have another route. My rookie year I always got it wrong. But just learning the game, studying film, listening to my coaches, figuring out the techniques of the team I’m playing that week, to know if it’s split safety or post high, was hugely helpful. Eventually you know it in a second. You won’t even have to think about it.”

When a player’s skills come together like this, football becomes, paradoxically, more complex yet simpler. Take, for example, the 3 × 1 formation that the Patriots (and many other NFL teams these days) love to employ. In that set, three receivers line up to one side of the field and one to the other. Because of his distinctive abilities, Gronkowski can align anywhere in this formation, creating the complexity. And because he’s such a matchup problem, where he lines up often dictates the defense’s coverage, tipping the opponent’s hand and creating simplicity for the offense. Though he hasn’t been targeted often from this spot, the Patriots love putting Gronkowski all alone on the 1 side, opposite the other receivers, especially in the red zone.

“When I first get out wide, I see what type of defender is on me. If it’s a linebacker or safety, you know right there it’s man coverage. If it’s a corner, you know it’s going to be mostly zone, because the corner is just staying out there in that zone area that he had already. [Depending on if it’s] man or zone, you can possibly have a different route.”

The chess match doesn’t stop here. What matters next is how wide Gronkowski is split out all alone on that weak side.

Let’s say you’re running a post route. If you’re lined up “all the way out, you have to get inside the DB off the line,” Gronkowski explains. “You also have to see where the safeties are playing. If they’re far away, you have to keep your route skinny.” Now, instead of being wide, say you’re flexed just a few yards outside the offensive tackle. Here, “you have more field to work with. So if it’s a post route from inside, you can possibly stem it a little outside now.”

Physically Gronkowski is the biggest, baddest pass catcher in the NFL, but it’s the nuances that push those traits to the next level.

* * *

Gronkowski is at the forefront of today’s evolving NFL. More than ever, tight ends are dictating matchups simply by how they line up. The most common NFL personnel package now features three wide receivers, one tight end and one running back, dubbed 11 personnel. According to Football Outsiders, teams have used this three-receiver set more each year since 2010. While it means more snaps for wideouts, the position that appears to be benefiting most is actually tight end. Compared with ’01, there was an 8% increase in the number of wide receivers with at least 50 catches or 600 yards in ’15. But the number of tight ends with at least 50 catches jumped by 183% compared with the ’01 season, from six to 17. The number of tight ends with at least 600 yards rose by 160%, from five to 13.

Some of this is because in three-receiver sets, offenses are more spread out, creating more space in the middle of the field where tight ends usually operate. But those tight ends are also becoming more athletic, and many offenses, when they’re not putting a third receiver on the field, are employing a second tight end.

That athletic tight end “is a glorified receiver,” says Bills offensive coordinator Greg Roman, one of the league’s most creative offensive architects. “He’s a guy that I really don’t want aligned close to the formation. Usually he’s just going to get beat up and banged around. So how do we use this guy to his fullest capacity? Split him out somewhere. Slot. Outside.”

“Call ’em whatever you want to call ’em, tight end or receiver, he’s a receiver,” Belichick says of the new-model tight end. “He catches balls. He doesn’t block [up on the line of scrimmage]. He might be attached or detached to the formation, but his blocking assignment is usually somewhere in the secondary, or he arc-releases [faking a block on the line, then swooping around to block a linebacker or safety]. So a lot of tight ends with those big catch numbers, we treat them as receivers. When they’re in the game with another tight end, it’s really 11 personnel. When they’re in the game with three receivers, it’s really four wide receivers.”

Here’s where Gronkowski sets himself apart from other great pass-catching tight ends—and maybe solidifies his place in history. Offenses can’t treat him as simply a receiver because, as Roman, a shrewd running-game designer, explains, “He can block like an offensive tackle. Nobody can run-block like him.”

New England has a power-based rushing attack. If a team pits only cover artists against Gronkowski, they risk getting mauled on the ground. Gronkowski credits much of his blocking development to Brian Ferentz, who coached Patriots tight ends in 2010 and ’11 and now is the offensive line coach at Iowa. “He taught me it’s always about keeping your feet running and keeping your hands inside,” Gronkowski says. “Like when you’re pushing a car. What are you going to do? You’re not going to push like a one-legged duck paddles. You’re going to run your feet, just like you’re running.”

People inside the Patriots’ organization also say that Gronkowski, on his own volition, learns not only his own run-blocking assignments, but also those of players on the other side of the offensive formation. That way he’s prepared in case Brady flips the direction of a running play.

The Patriots obviously recognize the value of having a true five-tool, running- and passing-down tight end. With Gronkowski, their two-tight-end package was already the league’s most schematically diverse. This year they’ve amplified that by trading for Martellus Bennett, a ninth-year pro who can do everything Gronkowski does, just not at quite as high a level.

“If you can run the same plays out of 12 [two-tight end] and 11 [three-receiver] personnel, it’s just a question of whether you have a 240-pound receiving tight end or 195-pound receiver doing the same things,” says Belichick. “The matchups are going to be different, but conceptually the offense is the same. That’s a lot easier than having one offense that, let’s say, only has two receivers in it, and then another offense that has three receivers. You’re into different protections, different running game, different play-action game. You have to handle situations like red zone, goal line, short-yardage differently. I’m not saying you can’t do it. It just changes the dynamics a little bit. Whereas if you have a pass-receiving tight end, you can essentially do a lot of what you do with three receivers; it’s just the matchup is different.”

When one of your tight ends is Gronkowski, different matchups mean favorable matchups. That’s because no safety, and certainly no linebacker, can consistently cover Gronkowski one on one, especially not if he’s aligning all over the field. And if you put a cornerback on Gronkowski, you have two more concerns: (1) Who then covers New England’s actual wide receivers? And (2) What happens to that corner if Gronkowski lines up in a three-point stance and run-blocks?

No one has dealt with this question more often than Rex Ryan. The former Jets and current Bills coach has faced Gronkowski a league-high 11 times.

“It’s tough to cover the guy no matter where they put him,” Ryan says. “They can put him at the outside position, they can put him in the slot, they can put him flexed or on the line of scrimmage, they move him all over the place, so you have to be dialed in on where he is. And you know he’s a guy that can run, but his size is probably the most imposing thing. And the other thing is he’s a guy that will flat go get the football. So you definitely have to be mindful of where he’s at.”

Keith Butler was an esteemed linebackers coach with the Steelers before being elevated to defensive coordinator last year. His debut was Week 1 in Foxborough. “I learned a lot from that game,” Butler says. In it, Gronkowski caught three touchdowns from three positions. He also did damage down the seams on play-action. If you remove Gronkowski from the Patriots, Butler says, “their passing game would take a big blow. Big blow.”

Indeed. Last season, when Gronkowski was on the field, New England averaged 7.27 yards per pass play. When he was off, that number plummeted to 5.24.

* * *

Given that defensive play-callers often game-plan around Gronkowski, his effectiveness all over the field is even more impressive. Not only does he need to digest all of his opponent’s different defensive looks—recall how three plays become 15, as Belichick explained—but he could also see double-team packages designed specifically around him, ones opponents would never show against anyone else. After all, defenses apply more double-team concepts to him than any other tight end. Here, Gronkowski’s impact is enormous. You could argue it’s the reason New England doesn’t have to invest in expensive wide receivers or pass-catching backs.

Take running back Brandon Bolden’s 63-yard touchdown in Week 12 against the Broncos last year (sidebar). Bolden ran a wheel route out of the backfield against linebacker Danny Trevathan. The field was snowy, making it difficult for Trevathan to turn and run when Bolden looped upfield. Normally that’s what a safety is for, to help over the top—especially if it’s a linebacker in coverage. But the Broncos dedicated the safety on that side solely to doubling Gronkowski. The Patriots, anticipating this, sent Gronkowski on a cross-field pattern, further dragging that safety away from Bolden’s wheel.

When it’s suggested that he should get statistical credit for such a play—say, something like 63 assisted yards and one assist touchdown, Gronkowski smiles. “You know something, why not?” he says. “I agree. I like that.”

The purest form of double coverage is 2-Man, which is basically one defender playing man coverage underneath a receiver and another playing over the top. It’s what the Broncos did to Gronkowski on Bolden’s touchdown. “I see that a lot, right there,” Gronkowski says, “which is cool. I love when my teammates take advantage of it.”

Patriots insiders insist that Gronkowski’s enthusiasm for his unnoticed contributions to the success of others is genuine. As one says, “Some guys in his position would be envied—and not in a good way—by his teammates. Not Rob. They admire him because he can be a nightlife guy and at the same time one of the hardest workers in the locker room.”

As the conversation in the Gillette break room carries on, the topics get more specific. There’s nothing Gronkowski can’t elaborate on. He’s asked about his mental process for reading the coverage on, say, second-and-10 near midfield, out of a traditional line-of-scrimmage tight end position.

Well, first off, “if it’s a 10-yard route on second down and you accidentally do a nine-yard route but you get wide open, that’s fine. Totally fine, 100%,” he says. But before that, “you have to figure out if it’s man or zone defense. Throughout the week you go over the opponent’s second-down scenarios. You go over their coverages. You go over their people. So when you put your hand down, it’s like you’re already watching the filming. Knowing something like, if this defender points to the safety, he’s going to be in man. Or if he’s way backed up, it’s going to be zone. You have to know by studying film that week.”

O.K. But what happens if your opponent on film clearly does one specific thing, but then you line up out there and see something totally different?

Gronkowski brightens: “That’s the game of football, right there.”

Read The MMQB Issue of Sports Illustrated in its entirety by subscribing here.