The CBA at Halfway, Part II

After discussing many important issues in Part I of this midterm look at the 10-year collective bargaining agreement that governs NFL owners and players, this section deals with the all-important issue: where is the money going? With billions of dollars coming into the game, there is always dispute about how much each side should claim as “their share.” The owners, to be sure, achieved their primary goal in this negotiation: to take more of it.

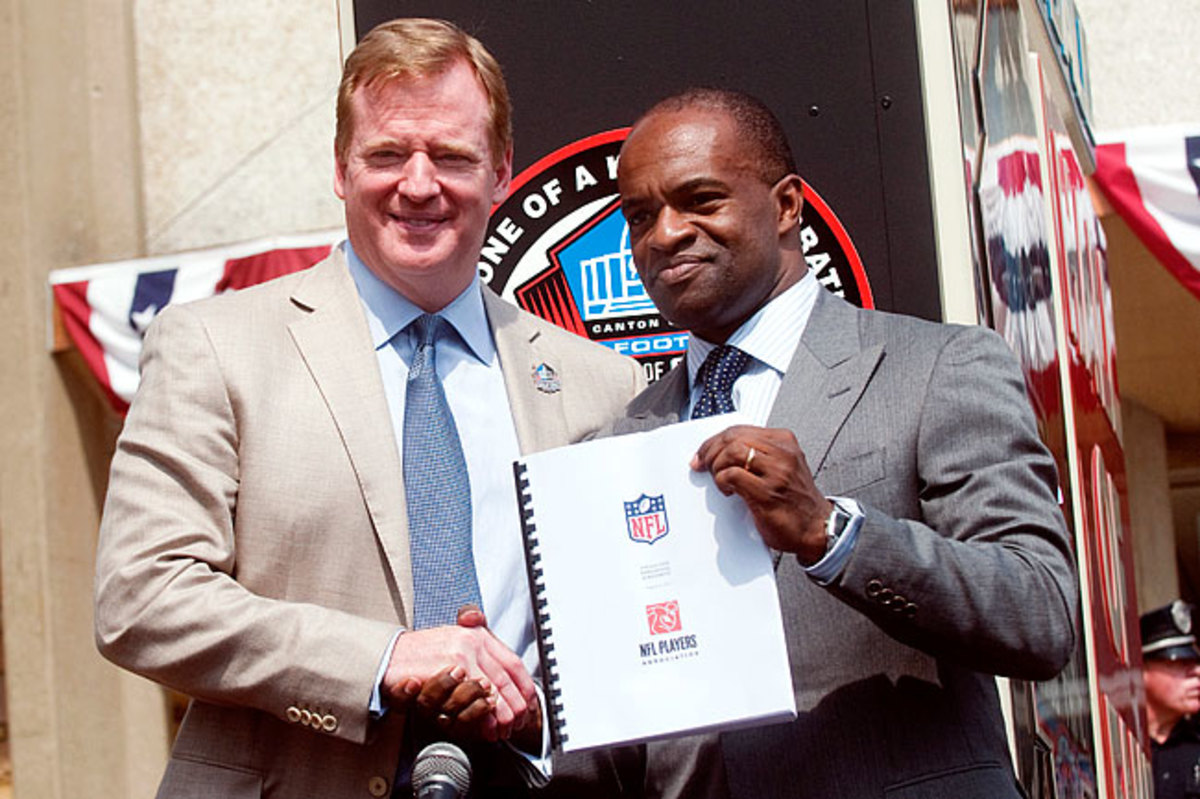

From the beginning of these CBA negotiations, the NFLPA was playing defense against an aggressive push by NFL owners who were intent on reversing the (literal) fortunes from the 2006 CBA extension, a deal that owners voted unanimously to opt out of before the ink was even dry. Having no success in bargaining and facing a lockout imposed by the league, the NFLPA strategy shifted from negotiation to litigation, as the union was dissolved to bring an antitrust lawsuit, Brady v. NFL (the lockout one, not the Deflategate one). Ultimately, after a negative result in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, the NFLPA made a deal to get players into training camp on time.

• BRANDT: The CBA at the Halfway, Part I

The league’s top priority was simple: become more profitable by lowering their largest expense, player costs. Owners charged Roger Goodell and the negotiating team—buttressed by “lockout lawyer” Bob Batterman—to forge an economic “reset” which, of course, meant making the players take a lesser share.

And take less they would. The players went from an approximately 50/50 split of league revenues to one that, calculated through a band of tiered percentages for national and local revenues, is now capped in the 47-48% range. Over a 10-year timeframe those couple of percentage points per year add up to billions of dollars moving from the players’ side to the owners. Thus, on this most important (some owners would say only) issue in collective bargaining, the owners scored a resounding win. It has enhanced the two things they care about the most: their bottom line and franchise value.

Packers Proof

During the CBA negotiations, owners used the Packers’ financial picture—the only one available for public viewing—as Exhibit A that increases in player costs were outpacing increases in revenue. Packers’ profit had fallen 71% (from $34 million to $9 million) between 2007 to 2011, and Packers’ president Mark Murphy said at the time: “There’s a strong sense that the current agreement went too far to the players.”

That was then, this is now. In June, the latest financial report shows Packers of revenue ($409 million) and profit ($75 million). More than half of their revenue came in the form of the league distribution of $222.6 million, the same amount for each NFL team. To put that number into perspective, the salary cap number last year for team spending on players was $143 million, almost $80 million below the league distribution amount alone.

• SUBSCRIBE TO OUR PODCASTS:Peter King | Albert Breer | 10 Things

The Packers’ snapshot is just one data point showing that business is booming for NFL teams, due in large part to reduced player costs. The new CBA did not have a cap amount exceeding the 2009 cap amount of $128 million until 2014, when the cap reached $133 million. While the past couple years have had double-digit million increases, the $35 million increase in team cap over five years (from $120 million in 2011 to $155 million this year) compares negatively to the NBA cap increase—for a quarter the number of players—of $24 million over one year.

The Rams just paid $550 million for the right to move. Forbes just gave NFL teams an average valuation of $2.34 billion. Record broadcast contracts are just now kicking in and show no signs of dissipating, with new suitors from the tech space poised to enter. To borrow from Murphy’s statement in 2011: There’s now a strong sense in 2016 that the current agreement went too far to the owners.

Let’s continue to follow the money.

The (Insufficient) Minimums

Team Thresholds

The insertion of language into the 2011 CBA requiring a team to have mandatory spending requirements on a cash, rather than cap basis, is an important step for the union. As I know from managing the NFL cap for a decade, cap spending is fungible; it is not an accurate barometer on team spending. Cash, however, is true accounting; it cannot be manipulated when it comes to showing how much a team is committing to the player side.

Section 9, Article 12 of the CBA requires teams to have minimum cash spending of 89% of cumulative salary cap numbers for the two four-year inspection periods: from the 2013 through 2016 seasons and from the 2017 through 2020 seasons. The first two years of the CBA, 2011 and 2012, had only league-wide spending requirements and no spending requirements for teams (as explained below, they took advantage of it).

These changes to team spending have allowed NFL teams to increase profitability and coast on player spending more than they should. Owners are given too much leeway in player spending and, as we know from their history, that is a dangerous proposition. Simply, the 89% threshold is too low a percentage and four years is too long an inspection period. Indeed, as of this writing more than halfway through the CBA, we are still waiting for the first accounting of team spending.

A further deficiency of the 89% spending requirement is that it doesn’t even apply to the relevant team cap.

Consider the following:

Adjusted v. Unadjusted Cap

Under this CBA, teams for the first time are able to carry forward remaining cap room to the subsequent year. These carryover amounts have been substantial, creating “adjusted” caps much higher than “unadjusted” caps. Yet the 89% spending requirement only applies to the lower amount. As an example, the Jaguars only need comply with the 2016 unadjusted cap of $155 million, not their adjusted cap of $190 million. As a result, while teams are meeting the 89% threshold based on the unadjusted cap, there would be many not meeting those minimums were they forced to spend their true adjusted caps.

Examples like this show how teams are able to skate on player spending. A more frequent and more stringent accounting of team spending should be an emphasis for the next round of negotiations.

League Threshold

The league-wide threshold of 95% of cap spending sounds nice, but has limited value. Heavy-spending teams annually carry roughly half the league that chooses not to. For example, the Eagles are spending over $206 million this year, more than $50 million above the cap, which carries a lot of teams with them into the minimum league requirements. The 95% threshold has not been a problem in any of the years of the CBA. The key is to have all teams spend and do so every year. The goal is not a collective spend; it is mandatory spend by each team.

The imposition of a cash-spending minimum in the CBA was a positive step, but with minimums that are too light and too long a view, it let the owners off the hook.

The Proof

Let’s look at the spending numbers—cold hard cash, not elastic cap—since the new CBA began. The numbers are courtesy of Spotrac, as both the NFL and NFLPA declined to release their tracking of team spending, perhaps for the same reason: that it presents ownership as taking advantage of the loose minimums.

First, in what I called the “freebie years”—when there was no accountingfor team spending in 2011 and 2012—teams did what we could have expected them to do with no one watching their player costs: they vastly under-spent.

2011

There were only nine (9) teams that spent above the $120.375 million cap. Eleven (11) teams spent below $100 million, with a low of $73.8 million by Tampa Bay, almost $50 million below the cap.

2012

Spending was even worse in the second year of the current CBA. There were only six (6) teams that spent above the $120.6 million cap, with a low of $83.7 million by Oakland.

Over the two-year period of 2011-2012, there were only six (6) teams with cash spending above the combined $240.975 million cap.

2013

In the first year of the team spending “inspection period,” only thirteen (13) teams spent above the $120.6 million cap. Four teams—Carolina, Oakland, Washington and Jacksonville—spent less than $100 million, with a low of $81.8 million by the Jaguars (more than $40 million below the cap).

2014

There were fifteen (15) teams—still less than half the league—that spent above the $133 million cap. There was a low of $103.9 million, almost $30 million below the Cap, by the Panthers.

Over the two-year period of 2013-2014, there were only eleven (11) teams with cash spending above the combined $256.6 million cap.

2015

This was the only year since the 2011 CBA when more than half the teams—nineteen (19)—spent above the $143.28 million cap. The low spending was $116.6 million, almost $27 million below the cap, by the Lions.

2016

There will still be isolated contract extensions around the league later in the season, but the vast majority of team spending for this year is done. There are now only twelve (12) teams, still less than half of the league, spending above the $155.27 cap; the Browns represent the low at $108.6 million, almost $50 million below the cap.

2015-2016

Over the two-year period of 2015-2016, there are fifteen (15) teams—less than half the league—with cash spending above the combined $298.55 million Cap.

2013-2016

Here is the reality of team spending on players: only twelve (12) teams have spent more than the four-year cumulative cap amount of $555.15 million.

They’ve exceeded that threshold by these amounts, in millions of dollars:

PHI — $55,344,695

DEN — $34,675,005

KC — $34,546,710

BAL — $24,630,165

SEA — $17,490,191

BUF — $15,796,376

MIA — $15,255,271

GB — $14,436,169

CHI — $7,688,067

SD — $7,643,871

NYG — $7,226,992

CIN — $1,492,088

The twenty (20) teams not listed here have not spent up to the cumulative cap over these four years. And this may be the biggest indictment of this CBA for the players: all teams are on track for meeting the team minimums! Coming into this year, the Raiders and Jaguars were tracking below the minimums when, perhaps not coincidentally, those teams were two of the biggest spenders in free agency and are now tracking above the threshold.

Thus, for the first four-year inspection period, it looks as though all teams will meet their minimum spending although there has only been one year out of five when more than half of NFL teams reached or went above the cap. That should not happen.

Allocation of Risk

Although there was much reaction this summer to eye-popping NBA free-agent contracts, many forget that we have similar gawking at NFL free-agent contracts every March (this year’s batch of golden ticket winners included Olivier Vernon, Malik Jackson, Janoris Jenkins and a few others). The difference, of course, is that while NBA contracts are fully guaranteed, NFL guarantees disappear after the early part of the contract (when teams have the lowest risk). NFL management smiles when agents deceive media and fans with reports of illusory guarantees and inclusion of no-risk first-year earnings into total guarantee.

We hear a lot of reasons why the NFL does not guarantee contracts—even from union leadership—that make perfect sense…for management. The primary reason is the high injury risk for NFL players, which, from a player point of view, is exactly the reason for guaranteed contracts. NFL contracts and the allocation of risk they provide have provided incredible value for teams, especially compared to other leagues. It is unfortunate that player contracts are so tenuous in the sport with the 1) most revenue, 2) highest franchise values, 3) greatest injury risk and 4) shortest career lengths.

Some further argue another myth: that collective player compensation would decrease with an increase in guaranteed contracts. NFL teams routinely shed millions of nonguaranteed dollars by releasing veterans, often replacing them with younger (and cheaper) labor and incurring a leftover cap charge. They would continue to do that with guaranteed contracts; they would simply have to pay real cash along with their cap accounting issue. There has been no data indicating anything other than continued growth in MLB and NBA player compensation despite guarantees regularly paid to released players. And it would add a side benefit: it would reward teams with better player evaluation and cap and cash management, further penalizing bad drafting and free-agent acquisitions.

In refusing to guarantee later amounts of the contract, teams hide behind an archaic NFL rule requiring immediate funding of future guarantees. This is an area the union, through its collective negotiations, needs to pressure for change. Further, player agents in individual negotiations should have the backing and support from the union in pushing the envelope for stronger guarantees, as benefits to the rest of the constituency will flow from there. Owners are obviously able to fund these guarantees; they resist because they can. The “guarantee” structure has become far too team-friendly; it needs to be revamped.

Beyond all the noise about commissioner discipline, franchise tags, practice and offseason limits, etc., here is the core issue of this CBA: teams are getting away with larceny on their most important expense, player costs. Simply, they are not spending or guaranteeing enough. This CBA’s shift in economic power has emboldened the NFL to treat the union as more of a nuisance than a formidable adversary. Their imposition of a new conduct policy while ignoring the union is a prime example.

Ultimately, the leverage in every business relationship goes to the side that is more comfortable with the status quo. When the next round of CBA negotiations arrives, the NFLPA will have the difficult task of changing the key issues mentioned above.

The owners’ status quo halfway through this 10-year CBA has them more profitable and powerful than perhaps ever before.

• Question? Comment? Story idea? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com