Through pain and grit, 49ers QB Steve Young finally gets that monkey off his back

The following has been excerpted from QB: My Life Behind the Spiral by Steve Young with Jeff Benedict. Copyright © 2016 by J. Steven Young. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved. Order your copy here.

I’m gripping a football with my left hand, standing on a perfectly manicured grass field at the San Francisco 49ers training facility in Santa Clara, Calif. I’m wearing cleats, gray sweats, and a red jersey bearing my last name—YOUNG—and number—8. No pads. No helmet. Practice starts in a few minutes. It’s a walk-through, a final chance to go over tomorrow’s game plan.

Deep in thought, I start spinning the football like a basketball on the tip of my left index finger. It looks geometrically challenging. But at this point in my life there isn’t much I can’t do with an oval-shaped ball made of leather sewn together by white strings. I’m thirty-three and I’m a professional quarterback. On weekend afternoons I run around a place called Candlestick Park pursued by eleven men who want to hammer me. I throw passes to Jerry Rice, the greatest receiver in the history of the game. I’m the MVP of the NFL and the highest-paid player in the league. I’m also a bachelor with a law degree.

Buy Now

QB: My Life Behind the Spiral

by Steve Young

It was the biggest game of Steve Young's NFL career, and he nearly missed it with a freak injury. The former quarterback for the 49ers tells the story behind the 1994 NFC Championship.

People think I live a charmed life. Maybe I do. After all, I play a boys’ game for a living. But it’s not just a game to me. It’s more like life or death. Standing here today, I feel as though I’m climbing Everest, nearing the summit. I’ve been this far twice before, yet never beyond. Today, though, I am determined to get to the top. Suddenly, threatening clouds gather and the sky darkens. There is a fierce headwind, and I have no ropes or safety harness. Fighting a building sense of nausea, I keep reaching, keep moving forward, like I always do. Almost there now. Then a familiar, heavy voice in my head says: What if I can’t get it done?

Ahead of schedule: Dak Prescott exceeding all expectations in stellar start to NFL career

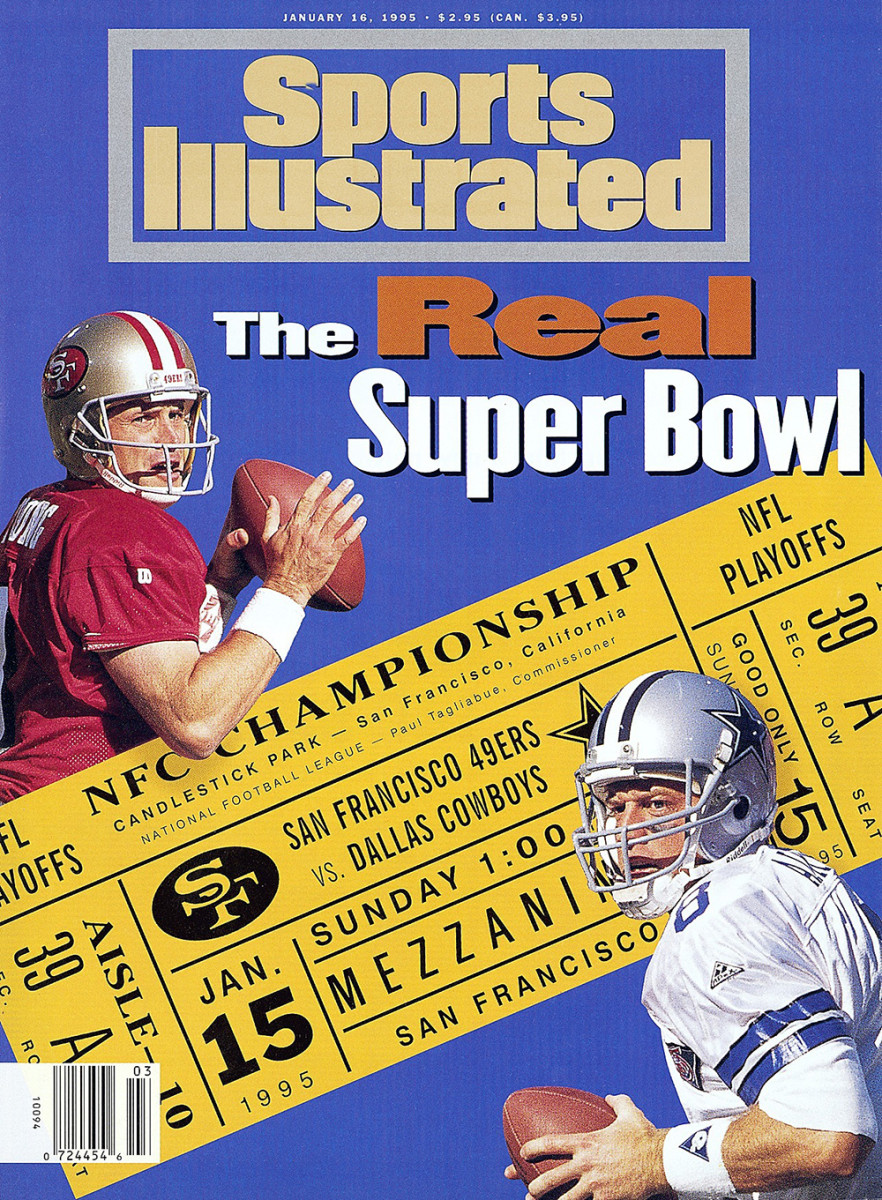

I hear that same voice before every big game. But today that voice is louder than ever. It’s Saturday, Jan. 14, 1995. Tomorrow is the biggest game of my life. We face the Dallas Cowboys in the NFC Championship Game for the third straight year. In 1992 and ’93 they beat us and went on to win back-to-back Super Bowls.

This year we are the two best teams in the league again. We are 14–3 and have the No. 1 offense. They are 13–4 and have the No. 1 defense. No AFC team can touch us. Whoever wins tomorrow will go on to win the Super Bowl. In short, San Francisco versus Dallas is the Super Bowl.

Our team owner, Eddie DeBartolo, hates losing to anyone. But he especially hates losing to Dallas. Around here, passing titles, MVP awards, and division titles are nice. But success is defined solely by winning the Super Bowl. Anything less is failure. That’s the Joe Montana effect. He won four Super Bowls before I replaced him. And that’s what I’m up against.

The team trainer is heading my way. He looks worried. I know what’s on his mind. It’s my neck. I jammed it a week ago in a playoff game against the Chicago Bears. After I ran for a touchdown that put the game away, safety Shaun Gayle drilled me. It was a late hit that sent me sprawling. I finished the game, but by the next day I had trouble turning my head. The medical staff has been working on me all week in preparation for tomorrow. Traction. Chiropractic adjustments. Electric stimulation.

This year my quarterback rating—112.8—is the highest in league history: over 4,000 yards passing, with 35 touchdown passes and just 10 interceptions. But I still run the ball more than any other quarterback. I have eight rushing touchdowns, and I average over five yards per carry. All week the Cowboys have been promising the media that they will make me pay if I try to run against them. My biggest nemesis is future Hall of Famer Charles Haley, the Cowboys’ six-foot-six, 255-pound defensive end. He’s one of the most disruptive forces in the NFL, and he used to play for us. Because of bad blood between him and our coaching staff, we traded him to Dallas two years ago. Big mistake. He helped them win two Super Bowls, and nothing motivates him more than knocking me down. His teammates say they are going to nail me, punish me the way Shaun Gayle did.

I’m mindful of Haley the way a surfer is mindful of a shark in the water. But once I take the field I fear nothing, especially not the hits. I might be the only quarterback who gets a thrill out of being chased. When I first joined the 49ers my teammates started calling me “Crash” because sometimes I initiate contact by lowering my shoulder and barreling into oncoming tacklers. I didn’t become a football player to run out of bounds. I want to experience every aspect of the game, including the physicality.

But there’s another reason I don’t shy away from contact. The physical beating I take on the field every weekend is therapy for the mental beating I go through each week just to get myself on the field. I am the fastest quarterback in the NFL. I can hit the whiskers on a cat with a football from a distance of forty yards. I have a photographic memory that enables me to visualize what everyone in the huddle is supposed to do on each of the hundreds of plays in our playbook. Still, on game day, I don’t want to get out of bed. It’s the riddle of my anxiety: I long to be the best quarterback in the NFL. I dread being the best quarterback in the NFL.

It’s hard to explain anxiety to those who don’t experience it. Deion Sanders thinks I’m too serious, too uptight. He goes by the nickname “Prime Time,” wears a red bandana on his head, and dances on the field. He tells me I need to learn to have fun. Fun? That doesn’t enter into it at all. For me, football is a quest. Quests entail overcoming hardship, trials of adversity in the pursuit of true joy. I’m now in my eleventh season in this league. I’ve had my share of hardships, adversity, and trials. I long for more of the joy part.

At nearly 40 years old, Randy Moss thinks he could still play in the NFL

It’s time for practice to begin. I bend over to tie my shoes. Suddenly, out of nowhere, something hits me with tremendous force. The point of contact is the crown of my head. I’m propelled backwards, landing on my back. Stunned, I look up. Defensive end Richard Dent is standing over me. He’s six-foot-five and weighs 270. “Steve, are you okay? I’m sorry, man. I’m really sorry.”

I grimace and reach for my forehead. What just happened? Dent explains. He had been playing catch. A teammate threw him a long pass. He was running and looking back over his shoulder for the ball when he barreled into me. It was a freak accident. Inside I laugh. Dent is third all-time in career quarterback sacks. He’s one of the fiercest pass rushers in NFL history. Eddie and Carmen signed him specifically to help us beat Dallas. Yet on the eve of the Dallas game he takes out his own quarterback. He extends a hand and helps me up. “I’m really sorry,” he says again. “I’ll be all right.”

But I’m not all right. My neck stiffens by the minute. By the end of the walk-through I know I’ve got a problem. A bump has formed on the side of my neck. Back in the locker room the trainer gives me ibuprofen for the inflammation and ice for the swelling. The muscles around my shoulder blades are tightening too. I don’t want my teammates to see me hurt.

The training room is empty. There the medical staff tries to break up the neck spasms with electric stimulation. That doesn’t work. So they try traction. That doesn’t work either. The entire area around my neck is too tight and too sore to manipulate. The rest of the team leaves for our hotel. I stay behind to get examined by the team’s physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist. Dr. Robert Gamburd starts by trying to test my range of motion. But I can’t turn my head in either direction. I can’t look up either. I can only look down. I feel like my head is in a vice grip. “I have to play tomorrow,” I tell him.

He goes through my options. I can wait and see if the ice and ibuprofen start to work. Or he can give me a steroid injection in my neck. Dexamethasone is a potent, fast-acting anti-inflammatory that will stop the spasms, reduce the swelling, and dull the pain for up to forty-eight hours. But there are risks: Pain is protective. Masking it may lead to more serious damage. Sometimes the injection causes more soreness than the injury. The injection can lead to infection. Unlikely. But possible. Finally, there’s no guarantee the drug will produce the desired result.

While he talks to me I talk to myself: What if I can’t play tomorrow? I have to play tomorrow. Can beating the Cowboys get any harder?

It’s now 2:30. Less than two hours since Dent ran into me. My neck hasn’t had much time to respond to the ibuprofen and ice. Maybe I should wait and see. In my fifteen-year career—eleven as a pro and four in college—I have played with plenty of pain. But I try to avoid putting chemicals in my body. “I can always give you the injection later if things don’t improve, ”he says. I agree to check in with him in a few hours.

I duck into the San Francisco Airport Marriott. The team stays here before every home game. I go to room 9043. My name should be etched above the door. It’s been my room since I joined the Niners in 1987. Tight end Brent Jones has been my roommate the entire time. We’re the only two players who share a room, something I’ve never appreciated more than I do now. The last thing I need to do the night before the biggest game of my life is to sit alone in a room, staring at the walls. Brent knows all about my anxiety. He talks me through my fears. He gets me from the hotel to the stadium each week. He’s more than a teammate. He’s a brother.

Brent is six-four and weighs 240, with thick, broad shoulders and a gregarious smile. He’s watching TV when I enter the room, holding my neck.

“Dude, what is wrong with you?” he says. “Bro, my neck is messed up.”

“What do you mean your neck is messed up?” “Richard Dent ran into me.”

He cracks up, thinking it’s just my anxiety talking again. “What?” he says.

“He was messing around. It was an accident.”

Brent shakes his head. “Dude,” he says, “you’re amazing.”

I know what he’s thinking. This is just Steve getting himself worked up before the game. I don’t bother trying to convince him that this time my fears aren’t all in my head, that the pain in my neck is real. I lie down on the bed and apply ice.

“What if I can’t turn my head tomorrow?”

“You’ll be all right.”

“What if this throws off my timing?”

“Bro, c’mon,” Brent says. “Brush it off. We have the NFC Championship game tomorrow.”

NFL Week 5 Blanket: Believe in the Falcons, because they're legitimate NFC contenders

A little while later he tries to get me to go to the team meal. But I’m in no mood for food. I don’t want to see anyone either. My absence at dinner prompts a visit from the trainer. He sees that my neck is getting worse and places another call to the doctor. Panic starts to set in. Team president Carmen Policy is briefed on the situation. Carmen wants to know the bottom line. The doctor tells him that even with the injection I might not regain enough range of motion to play effectively. But at this point, without the injection, it’s a safe bet that I won’t be able to play at all.

Carmen faces a series of decisions. Does he report my injury to the league? Does he tell Eddie? What about our players? He opts to say nothing. If he tells the NFL,then Dallas will find out, which will only motivate Charles Haley and company to really come after me. He doesn’t want to tell Eddie; his mercurial temper will erupt. And there’s no point in telling the team. The news will only shake players’ confidence.

I have no choice. At 5:30, Dr. Gamburd enters my hotel room with his medical bag. No one else is in the room. I don’t say much. Nor does he. I lie face down on my bed while he prepares a needle with four milliliters of dexamethasone and a small dose of Novocain. His fingers probe for the spot on the back of my neck between the third and fourth vertebrae. Then comes the pinprick, followed by a cold sensation that overtakes the inflamed area. I just breathe. “Try and take it easy for the rest of the night,” he says, and then he leaves.

I roll over and close my eyes. But I’m preoccupied. Too many thoughts: Two straight losses to Dallas. Two missed Super Bowls. My neck. Pass protection. Charles Haley. Losing is not an option. My whole career has been building toward this moment. I have to play. I have to get it done this time.

Before lights out I walk down the hall to Bart Oates’s room. He’s the starting center. In football a unique relationship of trust exists between a center and a quarterback. Every play on offense begins with me lining up behind Bart and barking out the snap count until he hikes the ball. The moment he delivers the ball into my hands his primary responsibility is my protection. If I get sacked, Bart takes it personally. If a defender goes after me, Bart goes after the defender. Sometimes he gets in fights for me.

He and I go way back. We were teammates in college at BYU. As a fellow Mormon, Bart is one guy who really appreciates the pressure I’m under. Not just to win football games, but to find my soul mate. Marriage and raising a family is at the core of our faith. I’m the most visible Mormon in the world, yet I’m alone. I’ve spent many a night at Bart’s dinner table commiserating with him and his wife Michelle about my situation.

On the night before games we have a routine. I gather with Bart and three other Mormon players on our team. Since all five of us are ordained priests and we are never able to attend Sunday services during the season, we typically give each other the sacrament in these pregame gatherings.

This time Bart senses that I’m in crisis. “What is it?” he asks.

I give him the abridged version of events.

“C’mon,” he says. “Your neck is jammed. So what? It’s no big deal.”

Typical Bart. Whenever my fears surface he downplays them. He’s always telling me not to worry so much. I don’t bother telling him about the injection. With the others looking on, Bart places his hands on my head and gives me a blessing. He says nothing about winning or playing well. He expresses gratitude for the life we live. And he prays for my protection and my safety. We’re not in a church. But I feel peace for the first time all day. I thank him and tell him that I don’t know what I’d do without him.

“Hey, tomorrow we are going to beat the Cowboys,” he says. “And you are going to lead us.”

I wake up. It’s morning, but still dark out. I sit up and turn my head. No stiffness. I have full range of motion. The steroid is working. I look out the window at the lights on the runway jutting out into San Francisco Bay. One jet lands, taxiing toward the terminal. Another takes off, slowly disappearing in the distance. One of the reasons I love this room is the view of the planes, especially around sunsets and sunrises. It’s calming.

But at this moment I don’t feel calm. One thought consumes me: We cannot—I cannot—go down three times in a row to the Cowboys. There can be no great effort that results in tough loss. That just won’t do. It CANNOT happen!

I stare out the window for a long time. Eventually Brent wakes up. I tell him that I’m not going to breakfast. My stomach isn’t feeling great. Plus, I don’t want to talk to anyone. He says he’ll bring me back my usual: two PowerBars and two bananas. That’s what I eat before every game.

I meet Dr. Gamburd in the training room at the stadium two hours before kickoff.

“How do you feel?” he says. “I’m going to play,” I tell him.

I remove my shirt and he observes the muscle spasms in my shoulders. The twitching is uncontrollable. He tells me it’s a result of the neck trauma. Then he injects Novocain into two trigger points above my left shoulder blade. I feel tingling, and then the spasms soon stop.

Offensive coordinator Mike Shanahan pulls me aside. He tells me that he’s making a last-minute adjustment to our offensive scheme. He doesn’t want to take a chance on Dallas getting to me. He’s going to use Brent Jones in pass protection as an extra blocker. He’ll be assigned to help out on Haley. That means Brent won’t be available on most passing routes.

At 11:30, I take the field to stretch and loosen my arm. It’s 65 degrees and sunny. But it has rained a record-setting sixteen straight days in San Francisco. The field is a mess. Groundskeepers wearing knee-high black rubber boots and yellow rain parkas work on the sod. Footing is going to be a problem.

Bucs K Roberto Aguayo redeems himself with game-winning kick against Panthers

Today is the first time the Fox Network will broadcast an NFC Championship game. John Madden is doing color. Pat Summerall has the play- by-play. They are on the field, chatting with players. I’m in no mood to chat. Not today.

I pick up a ball and start rotating my left arm like a windmill. The Eagles’ “Life in the Fast Lane” is playing through the stadium sound system. I throw the ball to Brent Jones.

“This is our time,” he says. I nod.

“Today Dallas is going down,” he says. I nod again.

Deion Sanders walks up. “Steve, you gotta do what you do today,” he says. “You gotta run it.”

After warm-ups we head back to the locker room. Brent removes a copy of the magazine Inside Sports from his bag. I’m on the cover, along with the headline: “Dallas Is Dead.” He hangs it on his locker. I feel sick to my stomach. Over 69,000 people are in the stadium. It’s the largest foot- ball crowd in Candlestick history. Millions more will tune in at home. The pregame hype is unprecedented. If Dallas wins, they are positioned to be the first team in history to win three straight Super Bowls. If we win, we are positioned to be the first NFL team to win five Super Bowls.

I run to a bathroom stall and kneel over the toilet. The antiinflammatory is making me nauseous. Suddenly my breakfast comes up.

Head coach George Seifert calls everybody in. The locker room is split-level. We pack into the lower part and take a knee. In a fiery speech, Jerry Rice reminds the team what’s at stake if we lose to the Cowboys again. “There’s no way!” he shouts, the veins pulsing in his neck and forehead. Fifty-two men respond with primal yells. Then we recite the Lord’s Prayer. It’s time.

I put on my helmet. The moment I look through the face mask a different voice speaks in my head: This is not just a game. This is a defining moment in your life. You are built for this.

This is the voice that propels me through the cramped locker room doorway into the tunnel. It’s exactly sixty-seven steps to the dugout that leads to the field. I love this walk. Condensation drips from the low ceiling. Cleats click-clack, click-clack echo through the tunnel. The rumble of the fans pulses through the concrete ceiling. Security guards nod as I walk past. “Good luck, Steve,” one of them says. I step to the ledge and the public address announcer thunders: “Steve Young!” I dart out. There is no turning back. I jog under the goalposts and through a gauntlet of teammates. The crowd noise is deafening, but I am silent. I show no emotion. I just want to get this thing started.

Dallas wins the coin toss and elects to receive. On the third play of the game, Eric Davis picks off Troy Aikman and returns the ball 44 yards for a touchdown. We lead 7–0. We kick off again. Three plays later Michael Irvin fumbles and we recover on the Dallas 39-yard line. I huddle the offense. I tell them we’re scoring again. On the fifth play from scrimmage I drop back. In a matter of two seconds I look left and pump-fake to Jerry Rice. He’s covered. I look over the middle for John Taylor. Covered. Brent Jones is in pass protection. I bounce on my toes and look to the right for my last option—Ricky Watters out of the backfield. Before he looks back I let it fly down the right sideline. He catches it in stride and races 29 yards to the end zone. Candlestick erupts. We are up 14–0.

On the ensuing kickoff, Kevin Williams fumbles. We recover on the Dallas 35-yard line. A few plays later we face first-and-ten from the Dallas 10-yard line. I call a quarterback draw. On the snap I take three quick steps back, as if to pass. Haley comes like a crazed animal around one end, creating a brief opening up the middle. Taking advantage, I head for the end zone. At the 5-yard line a linebacker hits my legs. I bounce off, but he wraps up my feet as another linebacker goes for my head. I duck just in time and land hard on the 1-yard line as another Cowboy jumps on my back. Second-and-goal from the 1.

The crowd loves it. My teammates love it. On the next play William Floyd scores. Seven minutes into the game we are up 21–0. It’s the first time in NFC Championship history that a team has scored three touchdowns in the first quarter.

I get on the phone with Coach Shanahan, who is up in the press box. He’s not satisfied. “Don’t let up!” he shouts in my ear. “The only way we’re gonna beat the Cowboys is we gotta go for fifty.” He’s right. We might need that much to beat these guys. I hang up and grab Jerry, Ricky Watters, and my offensive line. “We’re going for fifty!” I yell at them.

Before the quarter ends, Dallas scores. They add another touchdown in the second quarter. We are up 24–14. But the momentum has shifted. With 1:02 remaining in the half, Dallas has the ball on its own 16-yard line. I expect them to run out the clock. Instead, Aikman throws three straight incomplete passes. Then the punter shanks it. We get the ball back on the Dallas 39. We still have time for a few plays.

Shanahan wants another touchdown. So do I. We advance to the Dallas 28 with thirteen seconds left. I approach the line of scrimmage and see that Cowboys defensive back Larry Brown is lined up opposite Rice. It’s single coverage. I purposely avoid looking at Jerry because I don’t want to alert the Cowboys. On the snap he breaks to the outside and streaks to- ward the goal line. I throw a perfectly arced spiral to the corner of the end zone. Jerry dives and catches it with eight seconds remaining. We go into the locker room up 31–14. Haley hasn’t gotten to me once. The Cowboys have no sacks.

We start the second half with a turnover. Not good. Moments later Emmitt Smith scores. Less than four minutes into the third quarter and Dallas cuts our lead to ten: 31–21.

The Cowboys start taunting me. “You’ve got a monkey on your back,” defensive back James Washington says. “Number sixteen. Joe Montana.” Joe’s shadow has always been long, but at this stage I’m no longer looking over my shoulder. This is my team and my quest. I tell myself: There is no better time than now to find out if I can do this.

With just under seven minutes remaining in the third quarter, we face second-and-goal from the Dallas 3-yard line. Shanahan calls another quarterback draw. But instead of rushing around the end, Haley stunts to the inside. The other defensive end does the same thing. The middle is jammed, leaving me nowhere to run. I scramble, find some space to the right, and break for the end zone. Linebacker Robert Jones lunges for me at the 3-yard line. I barely elude his outstretched arms when James Washington lunges for my shoulders. I duck and his thigh slams into my head. He goes down. But I stay upright until defensive tackle Chad Hennings slams into my left side and falls at my feet. My body spirals over his, and I land atop Washington and Jones, which means I’m not down. My knee hasn’t touched the ground. I make a final lunge and extend my arms. The ball crosses the goal line. Touchdown.

We’re done! We’re gonna win this game! I spring up and fire the ball into the ground, staking a flag atop Everest. I’ve finally reached the summit. I let out a guttural yell. Candlestick is deafening. I have never heard it this loud. Jerry Rice wraps his arms around me. Brent Jones and Ricky Watters surround us. Their lips are moving, but I can’t hear what they’re saying. Noise never sounded so soothing; exhaustion never felt so rejuvenating. With 6:53 left in the third quarter, we are up 38–21.

When I reach the sideline Richard Dent smacks my helmet. “Way to go, Steve! Way to go.” I don’t have the heart to tell him that I reaggravated my neck injury on the touchdown run.

The medical team is waiting for me when I reach the bench. I sit be- tween two trainers and Dr. Gamburd stands, facing me. “How do you feel?”

“It hurts to look left,” I tell him. “Which side did you get hit?”

“On my right. But it hurts to look left.”

I remove my helmet, and he starts to manipulate my neck with his hands. It’s painful. But no amount of pain can overcome the relief I feel. The fourth quarter goes by in a flash. With 1:44 remaining, all that re- mains is for us to run out the clock. I break the huddle and follow Bart Oates to the line of scrimmage. I flash back to the first time I ever took a snap from Oates.

It is my freshman year of college and my first day of practice. Oates is a senior. I line up behind him, and he hikes me the ball. Backpedaling, I trip, fumble, and land on my butt. Everyone laughs.

“This guy sucks,” Oates says.

The coach says, “Young, you’ll never make it as a quarterback.” Now I line up behind Oates at Candlestick in the NFC Championship game. He snaps it. This time I don’t stumble. I kneel. The mud at my feet feels like heaven. Dallas is out of timeouts. I wish time could stand still.

My linemen—Steve Wallace, Jesse Sapolu, and Harris Barton—smack my helmet. Brent Jones, Jerry Rice, and John Taylor point at me. I love these men. For the first time all season Dallas has gone an entire game without registering a sack. And we are going to the Super Bowl. I have finally made it in San Francisco.

I huddle the team one more time. Every fan in the stadium is standing. Clapping. Cheering. I look up and see the scoreboard flashing that I am the Miller Lite Player of the Game. I smile. I’ve never had a beer in my life. I’m a thirty-three-year-old dry Mormon. Oates looks at me in the huddle. “Enjoy this moment,” he says. The cheering reaches a crescendo. “Release, man,” Oates says. “Savor it.”

I approach the line of scrimmage. I take the final snap of the game and take a knee. Time runs out. I bounce up and congratulate the Cowboys defense for a hard-fought contest. Then I find Aikman. He congratulates me. I thank him.

Echoes of “Steve! Steve! Steve! Steve!” pulse through Candlestick. I’m still holding the game ball. I raise my hands above my head. Candlestick is finally my house. I want to visit every room. I want to touch every fan.

NFL media roundtable: Picking top storylines as season goes forward

I run toward the back of the end zone and jump the guardrail. The fans mob me. I climb atop the Giants’ dugout and thrust my fist in the air. “Steve! Steve! Steve! Steve! Steve!” I still have my helmet on. I still have the ball. I jump down from the dugout, tuck the ball under my arm, and start running. I don’t know where I’m going.I’m just running. Television cameramen, photographers, and fans follow. I have never done a victory lap in my life. I’m always so buttoned up, so restrained. But today I am unleashed. I run all the way around the stadium, slapping hands with fans who line the route. By the time I make it all the way around the stadium I’m running on pure adrenaline. Owner Eddie DeBartolo is waiting for me at the steps of the stage erected in the south end zone. He’s wearing a white shirt and tie and he’s holding a brand new 49ers championship baseball cap. He slaps my hand. “You did it, Steve. You did it!”

In the locker room I run into Carmen Policy. He hugs me as if I’m his son. I kiss his cheek as if he’s my father.

“You deserve this,” he says. “You earned it.”

My eyes well up. All I ever wanted was to please these guys, my teammates, and the fans. My body is famished, dehydrated, fatigued, and bruised. But that’s not why I’m crying. The joy that I feared would never come finally has. My uniform is drenched in sweat and caked in mud. But long after every one of my teammates has showered, I’m still in my pads.

I want to take in the view from Everest.