The Chain of Responsibility in the Josh Brown Debacle

It’s déjà vu all over again for the NFL and one of its teams. We are reliving 2014 as the chilling specter of domestic violence infiltrates the NFL in a public and uncomfortable manner. Now, instead of the Ravens and Ray Rice as the key protagonists in this drama along with an unenlightened NFL, the characters are the Giants, Josh Brown and (what we thought to be) an enlightened NFL.

The script from the eight-part Rice and Brown episodes is the same:

Part I: An important player on the team is shown to have an incident (or incidents) of domestic violence with his future wife or ex-wife.

Part II: The team supports the player after the incident(s) with no discipline applied.

Part III: The NFL imposes light discipline (suspensions of two games and one game, respectively).

Part IV: Media outlets release shocking new detail about the incident(s).

Part V: A firestorm of public outrage and scorn ensues.

Part VI: The NFL reacts with further league discipline (indefinite suspension for Rice, more discipline expected for Brown).

Part VII: The team reacts, cutting ties (or expected to cut ties) with a player they supported at every previous turn.

Part VIII: The player appeals (or is expected to appeal) the “double jeopardy” of such new discipline and termination.

There is much to unpack here, but the best way may be to look at the parties involved for this unfortunate replay from 2014.

The League

When looking back at his tenure 50 years from now, Roger Goodell will be remembered as the Conduct Commissioner. I noticed this from the moment he took power from his predecessor Paul Tagliabue, a lawyer who would allow cases to slowly wend their way through the legal system before applying any discipline, if at all. For the past ten years, there has been a new sheriff in town, holding dear to his CBA-granted power to discipline players over their conduct.

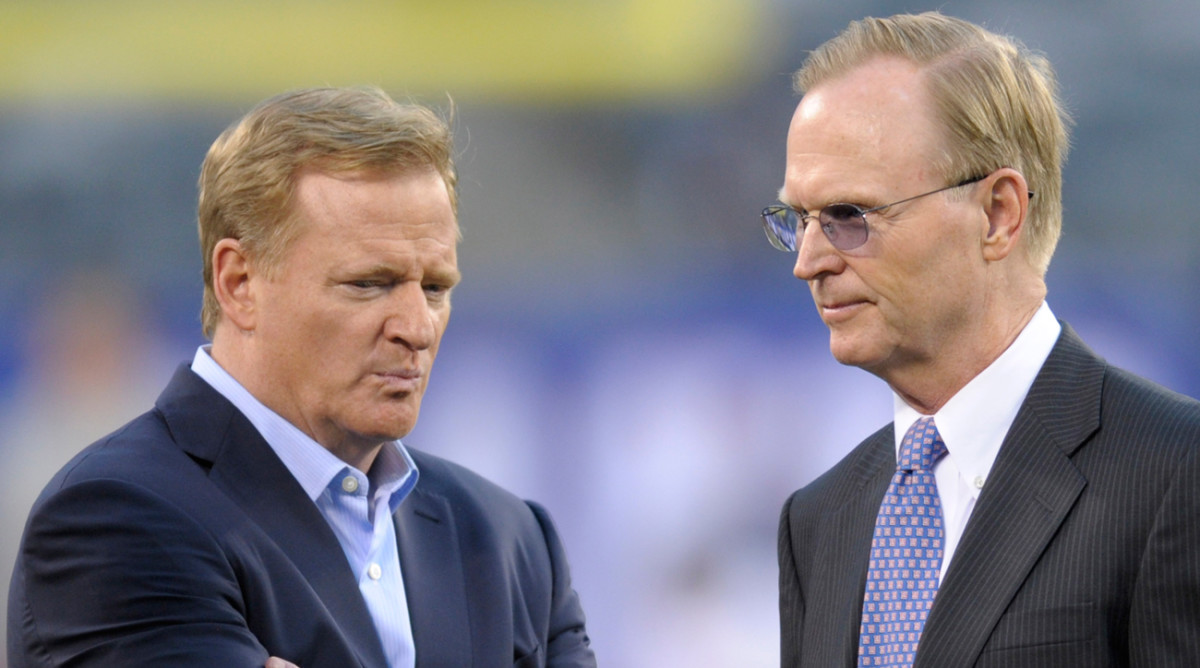

The problem with Goodell’s prioritizing of player behavior is that when that power is mishandled, as he admitted with the Rice matter, the spotlight is harsh. The Josh Brown episode draws an even harsher spotlight because of (1) the changes Goodell and the league had promised after the Rice fiasco and (2) the close relationship between Goodell and Giants owner John Mara, raising the ominous perception in this instance of the commissioner doing a “solid” for a friend who, of course, is one of his employers.

After the missteps with Rice, the NFL sprung into action. It hired—and placed at senior levels of the organization—Lisa Friel, the former head of sex crimes prosecutions in the New York District Attorney’s office, and Cynthia Hogan, a drafter of the landmark Violence Against Women Act in 1994. The league brought on domestic violence consultants and surveyed women’s groups, corporate and military policies, etc. to “get it right” on this issue. It kept Adrian Peterson and Greg Hardy off the field all of 2014, awkwardly using the little-known commissioner’s exempt list, with sponsors braying and fans/media raging at the gates. It implemented, without NFLPA input, a new conduct policy that included use of the exempt list, paid leave and a baseline of a six-game suspension for the first domestic violence offense. Finally, after being called out for a slipshod investigation on Rice, the NFL supposedly beefed up its security and investigative teams to do better in this area and to rely less on law enforcement in its investigation and discipline.

Now two years later, we are stuck in an unfortunate replay.

• THE ROOKIE QB WAITING GAME: Why Christian Hackenberg and Jared Goff can’t get a game

In the face of initial public criticism of Brown’s one-game suspension, the NFL’s statement focused on being unable to interview Brown’s ex-wife. Really? Wouldn’t the reluctance of the victim (not uncommon in domestic violence incidents) have been one of the first things experts such as Friel and Hogan would have advised the league two years ago? A further embarrassment came from the sheriff investigating Brown’s past incidents in Washington, who remarked that the NFL’s investigative efforts included information requests from a local man with no NFL identification, using his personal email account. This was the enhanced and improved investigation process that came out of the lessons from the Rice debacle?

Obviously this is not good for a league still struggling with public trust; Goodell’s vague and unresponsive answers on these (and other) issues do not help. The placement of Brown on the exempt list (with paid leave) and expected further discipline will appear reactive no matter the explanation.

One suggestion to Goodell: although he is ready, willing and able to take the heat on all of these issues: a fresh voice perhaps Friel or Hogan, would be advisable here.

The Team

Not to defend Goodell and the league, but compared to the Giants they were not totally asleep at the switch here. At least they imposed some discipline on Brown.

Giants owner John Mara is not only a trusted counselor and confidante to Goodell, but has appeared open, honest and thoughtful in the past. In this case, however, Mara’s admission on radio last Thursday regarding Brown—“He certainly admitted to us that he abused his wife in the past”—was shocking considering there was no discipline attached. I understand that Mara wanted to be supportive with Brown, but it will be interesting to see if he succumbs to public pressure and walks back from that support. The rhetorical question must be asked: Instead of responding to fans, media and even perhaps other owners storming the gate, will Mara not stand by the courage of his convictions and continue to support Brown as he has? My sense is that he will not.

I often talk of greater talent allowing for greater tolerance in sports (as all businesses), and the Giants have shown great tolerance with Brown, whom they knew to be an abuser of his ex-wife. My sense is that there were discussions among the team’s management and coaches about the importance of having a veteran kicker like Brown, with a response from someone—either coaching or management or both—to the effect of: “Hey, we can’t find a kicker on the street that we can trust more than Josh; we need him!” The talent factor—even for a kicker—overrode the inexcusable behavior.

• PETER KING’S MMQB: Cards-Seahawks incompetence, Stafford brilliance, more

Even if we are to give the team the benefit of the doubt in not knowing the full extent of Brown’s actions, the same question asked regarding Rice two years ago must be asked: What more did they need to see/read/know before realizing their player was abusing his partner?

I said this regarding the Ravens and Rice and will say it here as well: Compared to Goodell and the NFL, owners skate in the court of public opinion. Teams don’t need to “leave it to Roger” for discipline, yet they continue to do so. The Ravens and Giants each applied zero, leaving Goodell to take the bullets for them after the league imposed light punishment, albeit some punishment.

Again, not a good look for a storied franchise.

The Player

As a lawyer I have some privacy concerns about Brown’s personal journals from his therapy—where he admitted abuse—being shared so publicly. However, the NFL and the Giants did not need these journals to know of his repulsive behavior, which included not just his arrest in 2015 but an incident at the Pro Bowl—which all parties knew about—that spoke to a pattern of behavior.

Brown’s actions should (and will) have consequences beyond a one-game suspension. He is now temporarily parked on the exempt list, with pay. However, unlike Adrian Peterson and Greg Hardy, who sat on the list all season, we expect Brown’s visit there to be short. We can sense that Brown will receive additional discipline from the league and a termination notice from his until-now supportive employer soon.

And when the Giants inevitably release Brown, it seems doubtful he will ever wear another NFL jersey; he is radioactive. The problem, of course, is that his current toxicity is based on information that the league and team knew or should have known.

• ANNIE APPLE: Why I Can’t Stay Silent after John Mara’s Comments

The Union

As light as this one-game suspension now appears, it was a suspension that the NFLPA, on behalf of Brown, appealed. You wonder what arguments union lawyers used to contend that Brown should avoid suspension, but the appeal was predictably denied.

With the NFL having ignored the union in its prescription of the exempt list, the NFLPA will certainly file an appeal on Brown’s placement on such list. And with further discipline from the team and the league likely, it seems just as likely the NFLPA will appeal once more. And to awkwardly paraphrase a Prince hit, we will “litigate like it’s 2014!” with the NFLPA arguing “double jeopardy” as it did with Rice. Rice settled with the Ravens; his indefinite suspension from the league was overturned in arbitration.

Despite favorable precedent from the Rice case, it will be interesting to see if the union pursues Brown’s case in light of other players—respected veterans Steve Smith and Torrey Smith among them—coming down hard against Brown. Will the union’s executive board, made up largely of veteran players, support the expenditure of time and resources on Brown’s behalf (after already appealing his case once) in the way such resources were expended toward Rice? That is not clear, although if we have learned anything about the NFL and NFLPA relationship this decade, it is that their default setting is dispute.

The overriding thought on what is going with Josh Brown is this: We are back to where we were two years ago, and it is not a good look.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.