Sam Wyche: A Thankful Heart

PICKENS, S.C. — Sam Wyche looks good for 71. Darn good. He stands in the garage on his 28-acre property 122 miles southwest of Charlotte, in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A couple of days earlier, he got on his bike and rode 19 miles on a path in and around Pickens and nearby Easley. “Man, that felt great,” he said. Not a lot of 71-year-olds ride 19 miles—and he rides his bike about five days a week.

They especially don’t do that nine weeks after receiving a heart transplant.

“This Thanksgiving,” Wyche said, misting up, “means a lot more than any Thanksgiving I can remember because I, by all right … I am about to lose it here…” And it looks like he will lose it.

“By all right, I shouldn’t be here. I mean, what if this person, however he died, what if that had not happened? What if he left 10 minutes later and had not been at the wrong place at the wrong time? … I wouldn’t be here.”

The mystery donor. Wyche hopes to one day thank his family, but that decision will be totally up to them. For now, Wyche’s purpose in life will be to encourage organ donation. He will push registerme.org online. He’ll preach organ donation every day for as long as he lives, the way he used to preach the most bizarre, imaginative offense in the NFL.

“I’m still not sure,” Wyche said on this 64th day of his new life, “that I realize how close I came to dying.”

* * *

This story is about football, about a heart transplant, and mostly about gratitude. During this Thanksgiving season, I went to South Carolina not only write to about Wyche, but also to record a podcast with him. You can hear Wyche tell his story—perfect for your Thanksgiving ride to grandma’s, or your plane trip to see your loved ones—right here:

I can’t promise you won’t tear up at some point. I did.

This is also a bit of a personal story. The first year I ever covered pro football, I covered Wyche. We were rookies in 1984, he in his first year as an NFL head coach with the Bengals and I as the 27-year-old beat writer for The Cincinnati Enquirer.

One of the reasons I wanted to write this story (and record such a memorable podcast) is because Wyche is one of the most unforgettable people I’ve ever covered, and one of the most interesting coaches.

The story starts in 1984.

* * *

At one of our first meetings, the day before the 1984 NFL draft, Wyche told me whom the Bengals were going to draft and said it’d be fine if I wrote it. He was possibly the most open head coach in NFL history. He just figured no one would ever know—and in the pre-internet days, no one did. With Wyche’s help, I aced five of the first six picks, in order. (I missed on late-first-round pick Brian Blados.) My sports editor’s jaw dropped when I hit on third-round pick Stanford Jennings, the Furman running back.

I picked up Boomer Esiason, the second-round quarterback from Maryland, at the Cincinnati airport on draft day in my two-door Volkswagen Rabbit, surreptitiously evading the car sent by the team to ferry him to team offices. Esiason wasn’t too happy trying to fit into the little car. “Welcome to the f---ing NFL,” he said with disdain when he saw his ride. That summer, I lived in the Bengals’ dorm at Wilmington (Ohio) College. Wyche was in the RA suite down the hall from my room, and he told me to just stop by if I ever had any questions, and I did—probably 10 times in five weeks. There were two pay phones in the dorm, so players—especially Esiason, and sometime wide receiver Cris Collinsworth—would stop by my room on the ground floor to use my telephone. I watched full training-camp practices on the Wilmington College sideline with owner Paul Brown, and one day I complained about the stifling heat and humidity. “Ever get tired of being out here four hours a day?” I asked. Wrong question. “Young man,” Brown said pointedly, “This is our lifeblood!” I took that as a no.

There are other stories, one involving Wyche and a tuxedo and a white rabbit … another involving Collinsworth and Wyche and a magic show at a Cincinnati group home at Christmas. Listen to the podcast and you’ll be entertained.

Wyche did have a fuse, though. There was the time, before a November game against Seattle, when he was convinced I’d brought a Seattle-area scribe to practice to spy on the Bengals. He lined his players up, called me out of the football facility, and ordered me off the premises, loudly, to the catcalls of the approving players. Then he called my editor saying he wanted me off the beat. I hated his guts for about three days. But it was hard to hate Wyche for very long. A few days later, it was like it never happened.

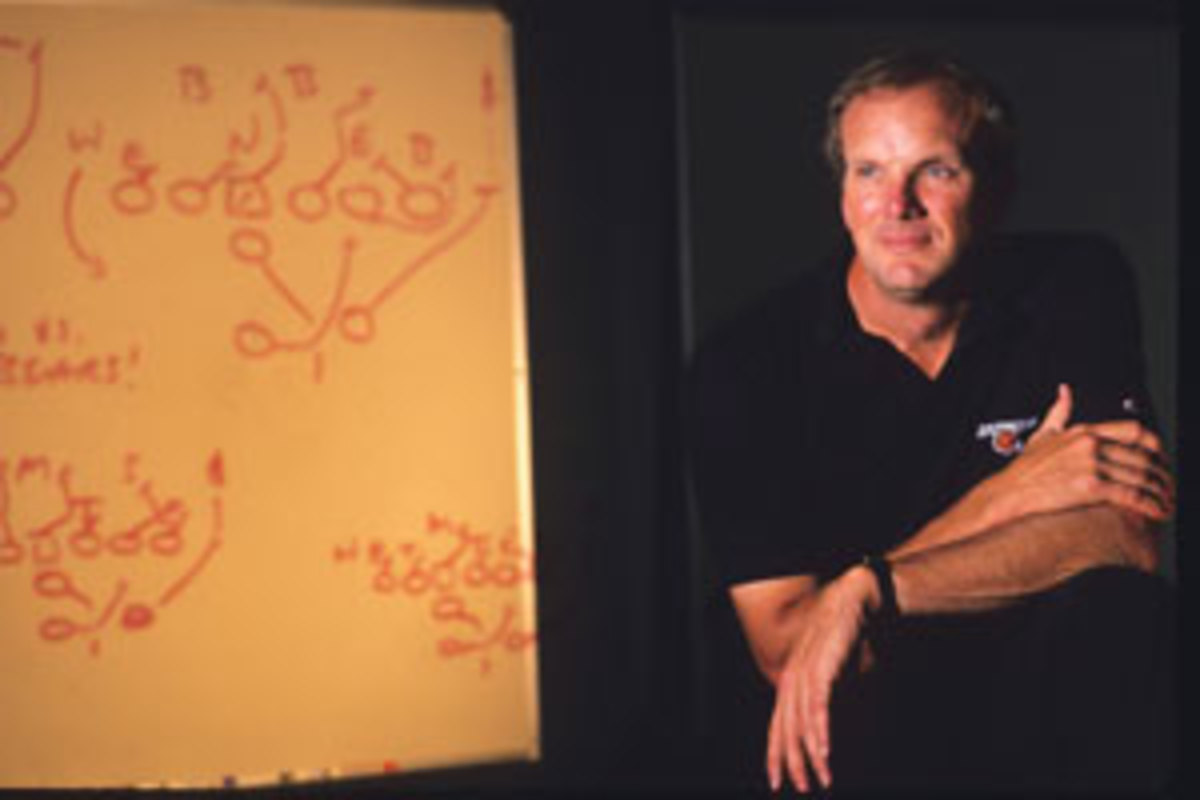

And the football stuff: Wyche was just south of Bill Walsh—one of his mentors—on the imagination scale. Wyche was Joe Montana’s first NFL position coach under Walsh with the Niners. By the time he got the Bengals’ head coaching job, in 1984, he was determined to do it his way. That included silly names for plays, and formations the players had never seen before. Like “Mantle” for a play that had a “61” in the long name.

“Sixty-one?” Esiason said.

“For Mickey Mantle and his 61-home-run season,” Wyche explained.

“Mickey never hit 61!” Esiason said. “That was Roger Maris!”

Wyche didn’t know that. “Keep it Mantle,” he said. “These guys won’t know Roger Maris.”

His way also included using something that no one did at the time except during two-minute drills: the no-huddle offense. In 1982, on the Niners’ staff, he saw what a weapon track star-turned-wideout Renaldo Nehemiah was on deep routes, and he thought, What if a speed guy like Nehemiah could tire out a secondary and a defense, and the offense went right to the line at the end of a play and prevented the defense from substituting? And when Wyche got the chance to run his own team, he eventually sprinkled it in, enraging the football establishment.

Along the way, he made enemies. He and then-Oilers coach Jerry Glanville had an intense rivalry that boiled over a few times. (Glanville believed football should be a smash-mouth slugfest; Wyche thought the game was ripe for trickery and innovation.) Wyche enraged the city of Cleveland when, after Cincinnati fans threw things on the field during a 1989 game, he said on the stadium PA: “You don’t live in Cleveland! You live in Cincinnati!” The league office repeatedly battled with Wyche, and nearly suspended him once, for his refusal to let female reporters in his locker room long after it had become common practice.

On the field, in the 1988 playoffs, Seattle defensive players faked injuries when the Bengals went no-huddle. And in the AFC title game, against Buffalo, Wyche got word (you’ve got to hear his full explanation in the podcast) that the league, angry that the no-huddle was making a mockery of the game, would call unsportsmanlike conduct if the Bengals used it in the game. There was nothing in the rules against it, but it looked so different. Wyche held his ground, claiming the league couldn’t change the rules right before the conference championship game. The Bengals used it, they didn’t get flagged, and won.

“I love Sam,” Boomer Esiason, his quarterback, said last week. “Sam and the coaches were the architects; I was the general contractor. I had to make things work on the field, and it wasn’t always easy. But we loved it! It was new; it was exciting; it was different. Sam made us feel like rebels. For five or six years, we were as unpredictable as any team ever in the NFL.”

One last football point: The Bengals and Steelers had an intense rivalry in those days. (Still do.) Wyche’s flair, one Steelers coach once said, made Chuck Noll’s blood boil. In Michael MacCambridge’s excellent book, Chuck Noll: His Life’s Work, the author says Noll called Wyche “Harry High School” and found the no-huddle “a borderline dishonest way to run a football team.”

In his garage last week, I asked Wyche about the rivalry and Noll’s seeming disdain—Noll wouldn’t shake hands after some of their games, though Wyche made the effort. Wyche never felt the frigid air between them. There was this story: “After I left Cincinnati and went to coach Tampa Bay,” Wyche said, “there was an NFL meeting in Hawaii, and I found myself with Chuck, of all places, on the beach taking a walk. He had one of these new things, an underwater camera, that he was excited about. Chuck was interested in so many different things. So we’re walking along, and he said to me, ‘Sam, did you know you’re the only active coach to have a winning record against me? You’re 10-6.’ ”

Wyche told me he didn’t know that. “I said to Chuck, ‘I just remember the losses.’”

Every coach remembers the losses. Esiason says young people today should understand a few things about a coach they may only vaguely know, if at all. “If I’m talking to a 35-year-old fan today, or younger, and they don’t really know Sam Wyche, what I’d tell them is: Sam was aggressive, he went against the grain, and he won. He got us to the Super Bowl. He was out of the box. That’s what I’d want in my coach.”

* * *

After his head-coaching career ended, in 1995, Wyche took a meandering path that began with TV (his left vocal cord was accidentally severed during an operation, ending a promising media career in 2000). He then worked as a substitute teacher and coached high school football in Pickens, where his wife, Jane, was born. In 2004, he was back in the NFL, working as an assistant on Mike Mularkey’s staff in Buffalo; he also served on the county council in Pickens.

He contracted the degenerative heart disease cardiomyopathy 13 years ago, and it was only a matter of time before his heart would give out. That happened on Aug. 14. Wyche was clearing some downed trees on his property with a chainsaw. When he walked back to the house after the job was done—a distance of maybe 15 yards up a very slight incline—he was out of breath. The next day, his cardiologist sent him to a hospital in Greenville, and for the next couple of weeks he underwent tests and generally felt lousy. On Sept. 1, Wyche entered a renowned heart facility at the Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte. They told him he needed a transplant. Days passed. Sept. 9 was the deadline for the installation of a pump that would help Wyche live longer but cause him to be mostly bedridden. He didn’t want the pump, fearing a strictly sedentary life. By then, Wyche likely had less than a week to live.

There are approximately 2,500 heart transplants a year in the United States; the Carolinas Medical Center averages about 25. “Coach was sick when he got here, and declining rapidly,” said cardiologist Sanjeev Gulati, the medical director of Heart Failure and Transplant Services at the facility. A team of about 15 at the center—including transplant surgeons, cardiologists, nurses and a social worker—meet each Monday to prioritize patients on the list, and Wyche’s condition was so dire he moved to the top of the list; if a heart within a several-hundred-mile radius could be found and harvested, and if it wasn’t a better match elsewhere, Wyche would have it. Easier said than done.

Carolina Panthers owner Jerry Richardson, a heart-transplant recipient himself, visited twice and sat on the edge of Wyche’s hospital bed, not in the adjacent chair. He told Wyche he’d be fine if he got a heart. “To these doctors,” Richardson said, “it’s just like changing a tire.” But he told Wyche an infection could kill him, so he should constantly wash his hands and use sanitizer—be maniacal about it.

No heart on Sept. 9, a Friday. No heart on Saturday. No heart on Sunday.

“I didn’t want to think about it too much,” Wyche said, “but I knew that I had the weekend to find a heart and if I didn’t find one, the only alternative was that I would go ahead and pass. Well, Monday comes along. Monday morning the doctor comes in.

“I was getting weaker and weaker, and it was literally hours, not days, that everything was going to shut down,” he said. “Reality set in. [The doctor’s] next sentence is, and I’ll never forget it: ‘Our plan is that this afternoon or maybe we’ll wait until the morning, but we are going to send hospice to make you comfortable for whatever time is necessary.’ ”

Sending him home to Pickens, for whatever time is necessary. “Those were his exact words,” Wyche said. “Make you comfortable for whatever time is necessary.”

“We didn’t think he was going to make it,” his wife, Jane, said.

“You hear the word hospice and so you prepare,” Wyche said. “You know how people say when you’re dying, your whole life passes in front of your eyes? Those next few hours, I really did have flashbacks to moments—from childhood, to a football game, to a class I had in high school, to scattered conversations, not just football, but life … the reality of death would always be the sobering thought to bring me back. I was laying still. I was short of breath. I felt the way you do when you have chronic fatigue, just flat-out whipped.”

That afternoon, unbeknownst to Wyche, two high school football teams in Cincinnati gathered on their practice fields. His son, Zak, is a coach at Purcell Marian High School. His grandson, Sammy, is a player at football power Moeller High. Wyche is well liked in Cincinnati still, and word had spread that he was awaiting a transplant, and time was short. Both teams, separately, gathered en masse on their practice fields and prayed aloud for Wyche.

That was at about 5 o’clock.

At nearly the same time at the Carolinas Medical Center, the doctor who’d gotten Wyche mentally prepped for hospice, came back into his room and said, “Good news. We have found a heart.”

For a heart to have the best chance for successful transplantation, it should be harvested and put into the recipient within four hours. This one took longer. Surgery began at 2:30 a.m., nine-and-a-half hours after they got the word of a donor match. Though Wyche doesn’t know the donor’s name, age or situation, the theory on the match is that Wyche was fairly healthy, lived a clean life, and the donor had a very strong heart. A surgeon from Wyche’s medical team harvested the donor heart—privacy laws prevent any disclosure of who donated it or where the heart came from, or how it was transported to Charlotte—and rushed it into the operating theater where another surgeon was removing Wyche’s damaged heart. In the wee hours of Sept. 12, the donor heart was placed in Wyche. The surgery, performed by a team of seven doctors, lasted four hours.

“In our business, I guess I can compare this to winning a Super Bowl,” Gulati said. “In the morning, when we had to tell Sam it didn’t look good and we had to prepare him for hospice, that’s like a dark cloud over our whole team. It was awful. You want to save this man because he’s got so much to live for. We gave it our best shot. He was sicker than sick, and I can’t predict how long it would be [before death], but it wasn’t going to be long. Then this is where luck, faith, God, incredible good fortune—whatever you’d want to call it—came into play. When there was a heart for coach, it’s like winning the Super Bowl, or winning the lottery.”

For about 48 hours, Wyche was woozy. On Wednesday, late in the day, he finally had his wits about him.

First thought: I’m alive.

Second thought: “I felt better than I had felt in maybe 10 years,” he said. “I just don’t know—there was an energy. I do remember one of the doctors telling me: ‘You’re not going to feel twice as good, you’re going to feel three times as good.’ Seriously: I felt three or four times better than I had in years. It was amazing.”

I asked Wyche: Do you remember what you were thinking as you were in and out of consciousness, or dreaming before you woke up?

“Yes,” Wyche said, taking on an air of mock seriousness. “It was really hot, there were lots of flames, it was pretty dark, and Jerry Glanville walked around the corner with a big grin on his face and said, ‘Sam, you’ll be fine.’ ”

* * *

Ten days after the transplant, on Sept. 23, Wyche was wheeled out of the hospital to his car. One of the nurses he’d become friendly with told him they weren’t sure how long he had to live before the transplant. She told him, “Boy, you really cut it close.”

However close he came, and however long he’ll live, Wyche wants to be an advocate for organ donation. “If I told you that you have a chance to save another person’s life … and you’re going to pass, and you’re not going to need your heart anymore, or your liver, or your pancreas, you would give it in a heartbeat,” he said. “All you do is go by the DMV and get an insignia put on your driver’s license. It doesn’t cost a dime. You’re not going to pay for the transplant. You have a chance to save somebody’s life … Infants can donate a body part. A 71-year-old man can do the same.”

One reason Gulati and his team are thankful this holiday season is that Wyche, he says, is the perfect patient and advocate for donation. “Sam’s so amazing,” Gulati said. “He says he’s been given this chance, and he’s not going to waste it, and he’s going to be thankful for this extra chance at life every day.”

For now, Wyche will ride his bike three to five times a week. He’ll live in his 30-by-30-foot luxury man cave a few yards from his house, isolating himself out of fear of infection. Jerry Richardson, you did your job: Sam Wyche is absolutely nutty about keeping germs away. When I met Wyche last week, he wouldn’t shake hands. “Fist bump!” he said, greeting me. He uses hand sanitizer all day long, and there’s a bed and a bathroom inside the man cave, with a gigantic 12-point elk head on one wall and three shotguns on another.

The Wyches have two rescue cats, two barn cats and four rescue dogs … all in the main house with Jane. Sam, for now, will not be around them. He stays out in the man cave, and works on projects in the garage, and rides his bike.

Before his Thanksgiving meal, he’ll say a prayer for a man he never met, the man whose heart beats inside his chest.

“I’ll give thanks to him. I’ll give thanks to his family,” Wyche said, choking up. “I’ll give thanks for another breath. I’ll give thanks for one more heartbeat. It’ll be a quiet Thanksgiving, but it’ll be a great Thanksgiving, one with more meaning than ever before. Thank God for this Thanksgiving.”

You can learn about the gift of life, organ donation, at registerme.org, or organdonor.gov.

• Question? Comment? Story idea? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com