‘A Very Attractive Man of Great Sexual Power’

Part 4

I’m the kind of man who’s never really on time, at least in the traditional sense. For me, five minutes late isn’t late at all. Seven minutes splits the difference between five and 10, but I round down, which isn’t late. Eight minutes gets rounded up, which is late but necessitates only a simple apology without explanation. Eleven minutes is really 10, so the same rule applies. But 12 minutes is starting to push 15. This requires a quick apology and an excuse: “Sorry, got stuck in traffic.” Anything beyond 15 minutes is truly late and you must offer a heartfelt apology and an elaborate excuse, citing wild events beyond your control. This can range from a death in the family to an act of God. Luckily, I live in Los Angeles, where being late has always been right on time.

As I came to find out on this particular Sunday morning, the exception to this rule is football meetings.

Things were already in full swing as I quietly slipped in through the back door. I was 16 minutes late and my mind had concocted outlandish excuses to have at the ready. “A volcano erupted on the highway, and my third cousin died of shock…” In front of me sat the entire LA KISS team of the Arena Football League. The players had jammed themselves into small desks like huge hermit crabs. The coaching staff stood in front of them like a menacing phalanx, their arms folded, permanent looks of disapproval affixed to their faces as the team reviewed tape from yesterday’s scrimmage. One player spoke in a voice just above a whisper, atoning for a blown assignment. I stood at the back of the room, where I tried to camouflage myself by “acting official.” Assistant head coach Walt Housman, a gigantic man with bad knees from years as a lineman with the Saints and various AFL teams, turned in my direction.

“Who the f--- are you?” he asked, an unlit cigar clenched between his teeth.

Good question.

If you're not one of the 272 people who have liked the Neal Bledsoe Fan Page on Facebook and thus share Coach Hous’s confusion: Hi, I’m Neal Bledsoe, actor, writer and retired Old Spice Man. Last year I tried out for the LA KISS despite having never played football before. I was following in the footsteps of George Plimpton, the venerable Sports Illustrated writer who joined the Detroit Lions, in 1963, for his iconic book, Paper Lion. But where Plimpton explored the chasm between the professional and the amateur, I wanted to understand what football is like when the rest of the world considers the pros themselves to be amateurs. I wanted to understand the drive that keeps these fringe players chasing an NFL dream.

I started by watching an open tryout, then sought advice from the AFL’s most famous alum, Kurt Warner, and finally, put my body on the line at an open tryout for the LA KISS, the team owned by rock stars Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley. The MMQB launched my appropriately titled “Delicate Moron” series last February, published another article in March and April, and then I disappeared … until now.

You might have guessed, but I didn’t make the team. Then again, I didn’t completely embarrass myself either. I had done well enough to warrant another look. Maybe not as a football player, but as a square-jawed curio from the softer side of Los Angeles who could ably serve as a tackling dummy. I was just above the “he might hurt himself” threshold, so the KISS invited me to embed with the players during training camp. Then, as it so often happens, events beyond my control conspired against me. (We’ll get to that in just a bit.) But here I was, standing in the football office, my cleats in one hand, pencil and paper in the other, and the eyes of the entire team staring me down.

“Who the f--- are you?” Coach Hous asked.

“I’m the writer,” I offered, both my apology and my excuse.

* * *

Professionals are paid for their services; it’s what separates them from amateurs. It’s a covenant that demands respect, fosters trust and implies some level of expertise. To be paid for work is a matter of pride and one’s identity. The thinking goes that a doctor is a doctor, a lawyer is a lawyer, and a football player is a football player. We have come to accept that pursuing a dream requires sacrifices, so an actor’s real job is being a waiter. But sacrifice is bleeding into other occupations as well. Day jobs, side-professions and gigs are part of the reality now. The men of the LA KISS were no different.

Between afternoon practice and evening meetings, defensive lineman Rodney Fritz picked up passengers for Uber and Lyft. Wide receiver DJ Stephens worked at Best Buy in the offseason. Quarterback Joe Clancy poured concrete in his hometown of Newburyport, Mass. Defensive back Clevan Thomas, an AFL Hall of Famer, worked as a corrections officer and “full-time dad” between seasons. Fredrick Obi, a young DB, helped his father do legal work and dreamed of becoming a real estate developer. Receiver Mike Willie helped out with his family’s landscaping business in Compton. Quarterback Nate Stanley sold industrial paint for the oil industry back home in Oklahoma. Even wide receiver Donovan Morgan, the undisputed star of the team, had a clothing business he was trying to start in the offseason—an undertaking he once described as “harder than anything in football.”

I was no different.

Immediately after my tryout with the KISS, I went back to work. It was the middle of pilot season, an annual event that spawns a great migration of hopeful actors from across the globe who descend on L.A. like herds of fame-thirsty Wildebeest. The hope is for one life-changing role, one lucky break, one wise soul to recognize your value, and—poof!— suddenly you’re George Clooney. That’s the Disney dream everyone wishes upon year after year.

I had wanted to make the KISS my sole focus. I told myself that even if Steven Spielberg himself cast me as Indiana Jones, I would say no. In fact I rehearsed that conversation in front of the mirror. I’d say, “Spiels, can I call you Spiels? No? All right then, Steve. Not even that? Steven? OK, Mr. Spielberg, I cannot play Indiana Jones because I am going to be a football player and I’m going to write about it for The MMQB. Call one of the Hemsworths, see if they’ll resuscitate your stupid franchise.”

That’s not entirely true, of course. I was simply having I quit fantasies. But I did make some rules for myself. I would accept a job only if it was truly life changing (Mr. Spielberg, please contact my manager) or filmed in Los Angeles, and even then I would do it only if they let me play football.

Within two days of my tryout that rule was tested.

I had been passing on pilots all season, but one particular script kept coming back around even as I kept saying no. My agents and manager begged me to reconsider. Still I said no. The producers asked if I would come in for a meeting (not even an audition) to “talk” about the project. I was skeptical as I sat down with them. My middle finger, injured by my inability to catch an errant throw just a few weeks prior, was in a brace. I hadn’t even showered following a practice earlier in the day. It was like the football player was holding the actor hostage. “This is me,” I said, “and if you want me you’ll have to accept the football as well.”

I told them, “The only way I’ll do this is if you can lump my days together and let me fly back on my days off to train with the team.”

The producers were a curious, if somewhat wary audience. I imagine it was the first time an actor had asked for time off from a TV show to play football. No one knew what to say. They looked at each other, deciding who would engage the slightly smelly man with the injured finger on the other side of the room. Finally, one producer cautiously chimed in, “Well, there’s always a solution.”

I said yes, but only if they’d keep their promise. What I hadn’t anticipated was the KISS going back on theirs.

I had spoken with Joe Windham, president and CEO of the team, and been cleared by the league to join the KISS on a two-day waiver. It was essentially another tryout. There were no guarantees, and if I hurt myself I’d be on my own (the same deal I made with The MMQB for this project.) I was fine with this arrangement. I had to be. In the Arena League, there is no such thing as a guarantee.

While the team was in its first week of camp, I was in the deserts of New Mexico filming a show about life on Mars. When I told the team I was getting ready to come back, Joe informed me that my “window for physical participation was closed.” I was furious but determined. I sent an email imploring him to reconsider, but received only a halfhearted reply. I knew I’d have to force the issue. So, after just the second day of shooting, I flew back for the team’s scrimmage. I had hoped to play in this game, but now I could only watch from the stands. No matter, my project needed to be rescued.

* * *

March 19, 2016

I took the first flight out of Albuquerque at 6:15 a.m. I was going to have less than 48 hours with the team, assuming they’d even still have me. I landed at LAX groggy but energized. I went home, grabbed my gear, including a bright red hat with white lettering that read “Make Donald Drumph Again”, and hit the road toward the Honda Center in the sprawling suburbs of Anaheim.

Anaheim is to L.A. what the AFL is to the NFL—or what I am to a movie star. If you squint just right it sort of looks the same, but up close there are very real differences. Whereas L.A. is famously liberal, Anaheim is traditionally a bulwark of the Republican Party. Anaheim and its environs are not just the home of Disneyland, but also the Trinity Broadcasting Network, the Crystal Cathedral and the cradle of Reagan conservatism. It’s very clean, with palm trees along wide avenues, chain restaurants and cookie-cutter homes—the American Dream on steroids, like an Archie comic come to life. But beneath its toothy whiteness there beats a dark heart. During the 1920s the city was run by the KKK, and just three weeks prior to the KISS scrimmage there had a been a rally for the Klan’s Anaheim chapter that ended in bloodshed. Anti-Klan protesters pummeled the local grand dragon and three people were stabbed; one was even impaled by the decorative bald eagle atop an American flag.

It’s a strange place that fosters strange people. It’s what happens when suburbs become cities but people remain isolated from one another. Anaheim, like the rest of Orange County, has always taken the idea of L.A. (palm tress and paradise), but too often has left what it actually is (global apex city and melting pot) on the other side of the fence. It doesn’t represent L.A., but rather the developer or theme park baron’s idea of what L.A. should be. It was here that the LA KISS made their home, and where the bad-boy, rock star image being sold to fans was in stark relief to the surroundings.

It was almost L.A. It was almost the NFL.

I arrived at the Honda Center, the home of the NHL’s Ducks, and took it all in. Ducks banners, gift shops and pennants were everywhere, but hockey was on hiatus and the concession stands and shops were all closed. There was a hush to the Arena, giving the building the feel of a high school on a Saturday morning. The only traces of football were two small signs declaring this the home of the LA KISS. They were taped to a merchandise table upon which jerseys, T-shirts, bandannas and Gene Simmons bobbleheads were piled high. A few people stopped and sifted through the souvenirs on their way to and from the bathrooms, which, as luck would have it, were still open. One fan, who wore a Gene Simmons jersey and had a tiny Gene Simmons puppet perched on her shoulder, posed for pictures with anyone who asked.

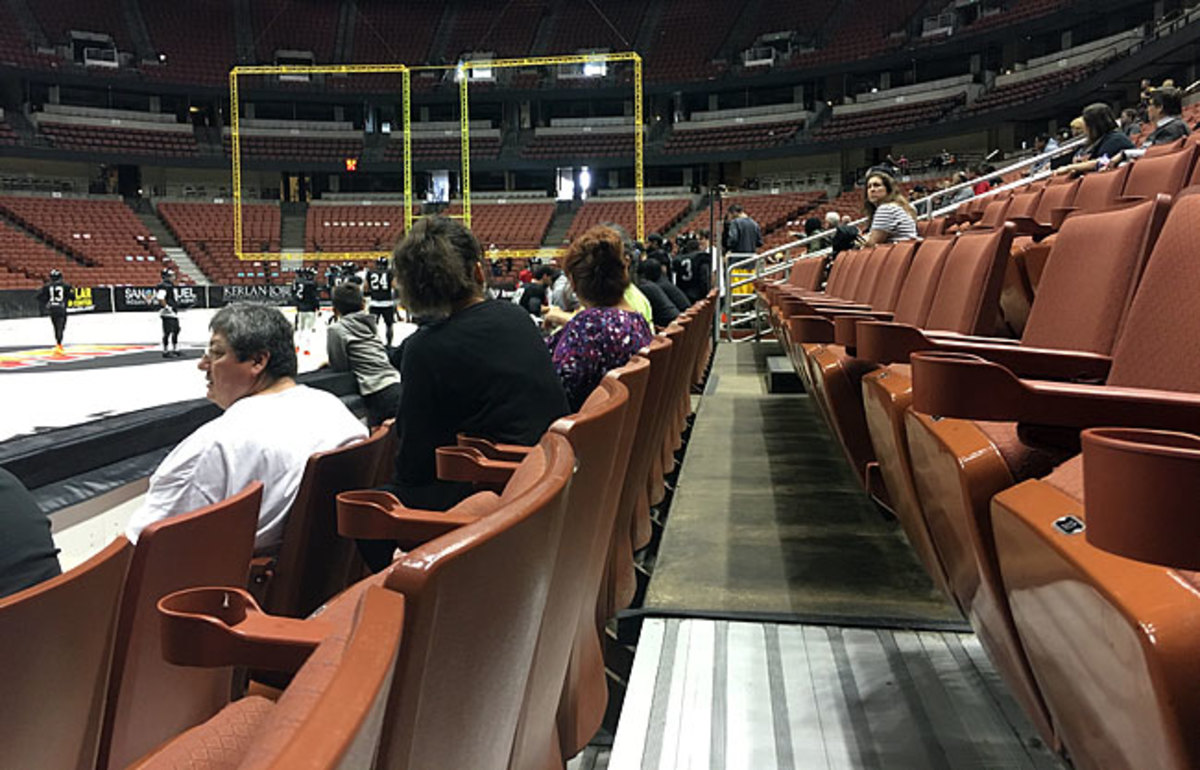

I had my pick of any seat in the house. There were maybe 40 people total in the stands. Throughout the arena, sheets of brightly colored paper displayed prices for season-ticket packages. The idea was for fans to sit in the seats they’d purchased. Some dutifully obeyed, but more than a few used the occasion to sit against the rail.

A VIP section was set up behind one of the end zones. Gene Simmons, Paul Stanley and Doc McGhee, the band’s famous manager, were all there. So was Joe Windham, a few PR flacks, team representatives and those KISS stars whose place on the roster was already confirmed. Guarding them was an officious duo of security guards, eyes on alert. Everyone else looked bored, idly chatting until the scrimmage began. I texted my PR contact, John Swidzinski, and waited for his reply.

A few players stretched and warmed up lazily on the gray carpet, where a black guitar pick, with “LA KISS” lit up by cartoon flames, made a splash as the midfield logo. Without warning, the scrimmage began. There was no fanfare, no fireworks, no starting gun for the hopefuls—simply a clap of the hands and a quiet acceptance that the time had come. New quarterback and presumptive starter Nate Stanley ran the offense. He was cool and surgical. He threw one laser and then another as he scored the first touchdown. It was as simple as depositing a check.

Ten minutes later John beckoned me to the VIP pit. He apologized for being late. He had to move Paul Stanley’s Tesla. “Work problems,” he explained. As soon as we reached the floor, John turned and pulled me in close. “Just so you know, Gene doesn’t shake hands,” he said, “only fist bumps.”

“OK,” I said, expecting something more.

“So, just to avoid any awkward situations.”

“Only fist bumps,” I said. “Got it.”

With that he led me toward Gene, who leaned against the padded rail of the end zone, one foot cocked jauntily on its toe, his eyes hidden behind the black mirrors of his aviator sunglasses. He turned his head to take me in and the two attendants who stood on either side of him took a silent cue and parted without command.

“You’re a very attractive man of great sexual power,” Gene told me.

“Thank you, and so are you sir,” I said, baffled at what else to do but return the compliment.

We bumped fists and Gene began to bait me with wordplay and puns. It seemed as if he wanted to test my intelligence with his wit. I cautiously played along, remembering his tense interview with Terry Gross of NPR’s Fresh Air. After a full minute exploring the meaning of great sexual power, I begged him to not to get bogged down by semantics. “I am not anti-semantic,” he replied, claiming victory in our verbal joust. He took his fingers as if he held an imaginary pen, licked the tip with his immense tongue, and crossed me off: another sacrifice to the God of Thunder. He looked around the VIP area for the two bouncers to endorse his victory, but all they offered were polite smiles and small nods of the head.

“Nobody knows what this is anymore,” he sulked, before performing the gesture over and over again, each flick of his wrist more florid than the last.

In the brief silence that followed John gave us a proper introduction.

“This is Neal,” he said, “the writer from Sports Illustrated.”

“Ah, yes! Well, welcome, welcome. We’re happy to have you here. Look around. Anything you need. And, um, did anyone tell you your hat is on backwards?”

“Thanks,” I said.

I remembered that he had once called Trump “the truest political animal I’ve ever seen,” but I didn’t know how he felt about the man, so I kept my hat turned away from him.

Gene and I were left alone to talk. I got the sense that he didn’t really know why I was there. But one thing became clear after five minutes: he didn’t know much about football. He admitted as much. He and Paul were rock stars, showmen, performers, and while there was a certain overlap as far as spectacle goes, he was in the dark when it came to the product on the field. He knew instinctively that spectacle means nothing without a winner. If he built that, he expected the people of L.A. to flock to them.

“People like winners,” he said. “In America, we like winners.”

He turned toward the field, gazed upon his players and the dozens of fans watching the scrimmage, and adopted a philosophical manner. “It about family,” he said. “That’s the most important thing, generations, families, coming together, watching the game, that’s what’s important, my father walked out on us when I was seven.”

That thought lingered in the air. I was unsure how to engage it. Was he using football to heal his own wounds? Before I could ask, Nate Stanley threw another bullet, hitting his wideout between the numbers.

“Look at that!” Gene whooped. “That was a nice throw! Good, crisp throws.”

The backup QB went in next. His first pass sailed high over the head of his receiver and into the empty stands.

“Ah, that wasn’t good,” Gene said.

“Yeah, he looked tentative,” I offered.

“Yes!” said Gene, surprised and delighted that I knew football.

“Who is that,” I asked, pointing to the backup.

“I don’t know, but he’s on the team.”

I asked Gene about the health of Arena football. Four teams had folded over the winter, including the league’s defending champion, the San Jose SaberCats, as had Vince Neil’s Las Vegas Outlaws, with whom the KISS shared a budding Rock Star Rivalry. Would this league survive? He responded by telling me about his joint press conference for an expansion team in D.C. to be owned by Ted Leonsis, the owner of the NBA’s Washington Wizards and the NHL’s Washington Capitols. Both men heralded this new franchise in the nation’s capitol as the way forward. It was all going be smooth sailing from here on out, he assured me. Losing those other teams was merely addition by subtraction.

Then, all at once, it was over. He grabbed me by the wrist as delicately as a grandmother and led me like a small child to the grandstand.

“Come on,” he said sweetly, “don’t you want to meet Paul?”

On my way to Paul, I met Mark Stroman, the man behind the KISS brand—for both the band and the football team. “You know we’re launching a new North American tour this summer,” he said. “But we’re not going to places like New York City or Minneapolis. We’re lining up places like Rochester and Duluth! We’re gonna be the biggest thing there, the biggest in years.” He spoke with the confidence of a carnival barker. His plans for the concert tour sounded an awful lot like an L.A. football team with its home in Anaheim. I kept climbing the steps and introduced myself to Paul, who stood next to one of the star players, Donovan Morgan. Paul is an extremely nice man, with an open and honest demeanor. He spoke of wanting to reach out to the community. “Is this L.A.’s team,” I asked him, “or is this Orange County’s?”

“We want this to the local team for Orange County,” Paul said. “We want this to be their team.”

Paul smiled. “We’ve got this one,” he said, throwing a thumb in Donovan’s direction. “He’s got muscles on top of his muscles.”

Donovan cracked an aw-shucks grin.

I asked them about the level of play, but Paul protested immediately. “These are the top 1% of players,” he said.

Donovan shook his head in frustration.

“This is a different game,” Donovan said. “In the NFL, if you’re down 21 with two minutes to go, people head for the exits. In this game, you down 21 with two minutes to go, that’s just when it gets good.”

As the scrimmage wrapped up, Terrance Smith came over and shook Paul’s hand before giving a slap-handshake and chest bump to Donovan and me. Then Mark Stroman strode confidently past us. “The first preseason game was a success!” he announced to anyone who would listen. “L.A. beat L.A., because they were playing with themselves.”

I descended to the field to seek out head coach Omarr Smith and beg my way back onto the team. When he saw me, his eyes lit up.

“What happened to you?” he demanded, his arms wide.

“Pilot season,” was all I could say.

“Did you get injured?” he asked eagerly, as if wanting to confirm a long-held suspicion, perhaps to tilt the balance of an office pool his way.

“No, I had to shoot a TV show,” I said. “I got my own show and it was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. Think of it like an NFL tryout. But I’m excited to get started with you guys.”

“All right,” he said with a grin.

I was back on the team.

* * *

March 20, 2016

There I was, 16 minutes late.

“Who the f--- are you?” Coach Hous asked.

“I’m the writer,” I said.

Coach Hous’s words hung in the air, prompting Coach O to stop everything and check for himself. This time he wasn’t smiling.

“You’re late,” he said, checking his watch. “You want to be a part of this, you gotta be on time.”

I had my excuses ready, but I wisely kept my mouth shut and just nodded.

Coach O went back to addressing the team. They were looking at kickoffs, examining the angles and coverages. When they wrapped up, Coach O popped his head around the corner again.

“You want to tell them what you’re doing?” he asked.

My chance to embed was gone and so was my anonymity. At this point, all I could do was tell them who I really was.

“Hello,” I began, scanning the crowd of heavy-lidded eyes and massive bodies. “My name’s Neal. I’m from Sports Illustrated. I’m going to be playing with y’all.” I began hearing myself and wondered why I was suddenly speaking in a drawl that refused to go away. “I’m here to see what you do. To tell y’alls story. I’ll be living with y’all at the hotel and playing with you on the field. So don’t be afraid to knock me around a li’l bit. I can take it.” Then, pausing for what I was sure was a killer joke at my own expense, I added, “Somewhat.”

No one laughed. They didn’t know what to say, or even seem to care. The first round of cuts had just come after the scrimmage. The team was whittling the roster down to the final 26, and now here was this lanky writer who showed up late. What? Why? Didn’t we already have enough kickers? I felt that they accepted me in a way they might accept a new restaurant for a team dinner or a new laundry policy for jerseys: just another bit of camp BS to ignore and survive. Coach O asked if they had any questions. They didn’t. He reminded us that we all had a 5 o’clock team dinner at JT Schmidt’s. With that, everyone was released for the afternoon.

* * *

I arrived at 5:30 p.m., thinking dinner was a window of time. Wrong again. Several of the big linemen had already gorged themselves on the caloric menu and were headed home. The players who were still there ate silently, staring at their phones or watching the second round of March Madness on one of the many TV screens perched above their heads. I wanted to get to know them, but no one was talking. I felt like the new kid in school, but the Swedish exchange student kid, an outsider who’d be going home after one semester.

Finally Coach Dave Watson invited me to sit down with him and Gustave Benthin, a massive but baby-faced nose tackle from Oregon. I was astounded to learn he had a kid back home. He seemed too young to be a dad. His quiet, sweet manner was at odds with his powerful frame, but he spoke with tenderness and a longing for home, his wife and his child. He was from a tiny town called Knappa, along the Columbia River just east of Astoria, where The Goonies was filmed. I told him I was from Seattle and had spent many summers in Astoria. He let me jabber on about salmon fishing until he politely excused himself.

One by one the players left, saying goodbye to Coach Wat and then, with hesitation, to me. I offered my fist to pound, thinking it was the appropriate way to say goodbye. A few players did, although they seemed more confused by it than anything. It was nice to know nothing had changed since high school.

Coach Wat and I were eventually left to talk. He had coached at USC and counted Pete Carroll and defensive legend Monte Kiffin among his mentors. His first season there he saw the Trojans lose a heartbreaker to Vince Young’s Longhorns in the greatest college game ever played, the 2006 Rose Bowl.

“This game is a father figure to these young men,” he said. “Coaches become father figures.”

I’ve always believed that there’s a dividing line between those who have played football and those who haven’t, as if it were a rite of passage. I asked Coach Wat if he thought playing football makes someone a little more of a man in America. “Absolutely. It teaches you grit, determination, loyalty,” he said. “It’s the greatest game on earth.”

I said my goodbyes and left for the Red Lion Inn, my temporary home, just south of Disneyland. There would be no film session, no other care in the world, except to rest up and wait for tomorrow. But I was restless. I had an audition the next day. Two auditions, really. I would try to prove myself as a football player, to show I possessed that grit and determination. After practice, I would pretend to be a dermatologist fighting the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco during the 1980s. My part-time job still demanded part-time attention, but my mind was consumed by football and I found myself unable to concentrate. Around 9 p.m. fireworks began to explode over Disneyland. I thought of the last time I was there. I had gone with a friend who passed away a few months later, leaving behind not just loved ones, but unfulfilled dreams. I wondered what she would think of these two lives of mine.

Part 1: A Man, the Arena, and His First KISS of Fate

Part 2:A Quixotic Bit of Foolery

Part 3:Judgment Play

NEXT FRIDAY: Neal gets to know his new teammates, nearly cripples himself and is—maybe, kind of, perhaps—almost poached by a rival football league. All that and more in Part 5 of the Delicate Moron.

Question? Comment? Story idea? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com