Famous, But Not in the Hall

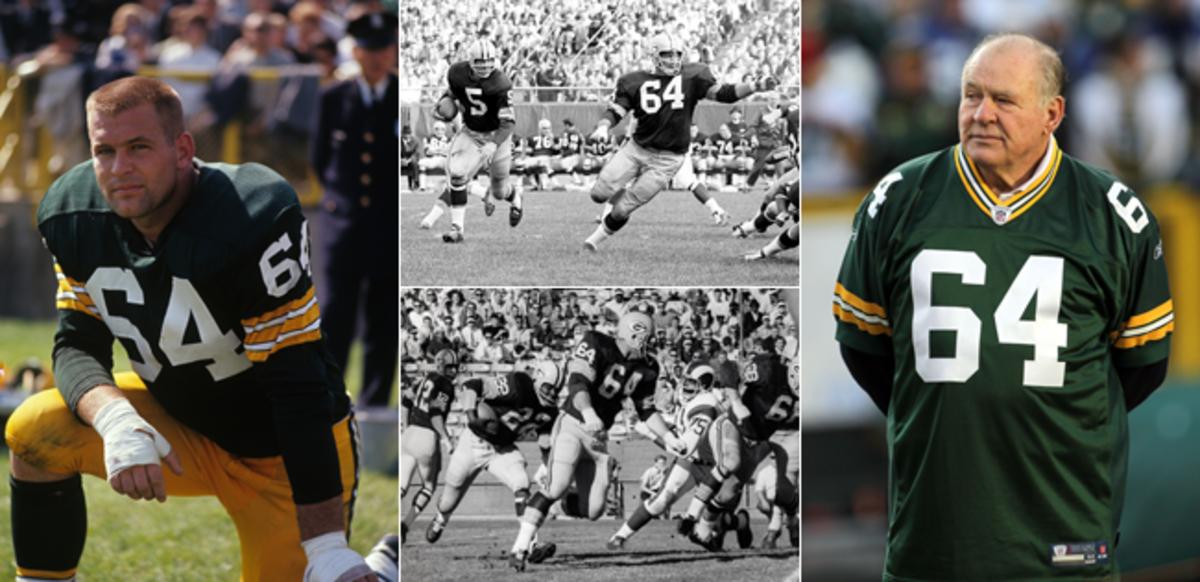

BOISE, Idaho — On a Friday night in New Orleans 20 years ago, Jerry Kramer sat in K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen, the renowned Cajun restaurant of chef Paul Prudhomme, and celebrated his 61st birthday. Kramer was in town as a Senior Committee finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Family and friends had flown in from as far as Idaho, Kramer’s home state. He was expected to be voted into the Hall, ending 24 post-Packers years of waiting and wondering. Wondering why the NFL’s widely regarded best guard of the ’60s, an iconic member of Lombardi’s Packers, a five-time All-Pro and a five-time NFL champion was not a Hall-of-Famer. And wondering why the same voters who had rejected him for Canton put him on the NFL’s 50th Anniversary Team in 1969. Kramer was the only member of that team not in the Hall. Befuddling.

But by the next evening, he knew, the issue would be moot. The Hall of Fame class of 1997 would be announced on Saturday, and Kramer would spend that night fielding congratulations and giving interviews. The following day he would watch his beloved Packers play their first Super Bowl in three decades, against New England.

Later that Friday evening Bryant Gumbel came by. So did Gary Hart, the former Colorado senator. And Jimmy Buffett. “It was a wonderful night,” Kramer recalls. “We had a great time, a fabulous dinner, a lot of stuff to drink—and we were celebrating, too. We allowed ourselves to get caught up in it.”

The next day, Kramer stopped by the set of ESPN’s “Sports Reporters” to hang out with his old friend Dick Schaap. On his TV headset, Schaap heard something and barked a response that stopped the room. “What? He what?” Then Schaap turned to Kramer.

“You didn’t make it.”

* * *

“That was probably the most difficult year—’97 in New Orleans,” Kramer, now 81, says. “I had allowed myself to look forward to it and get excited about it.” Kramer is sitting in a white leather recliner in the open-loft living room of his home. Through the windows you see gradually industrializing farmland; behind that, the snow-covered Boise Foothills. Walls and display cases are filled with family photos and football memorabilia. Kramer, who grew up eight hours north of Boise in the town of Sandpoint, has lived in this house for 15 years. His daughter Alicia, who is also his business manager, lives with him, along with Alicia’s 4-year-old son, Charlie. Kramer spends his days traveling and working with a group that researches nanotechnology to increase helmet safety. He’s also involved in stem cell longevity with a company in Houston. He recently underwent a stem cell procedure to combat the ailments that cause him to hunch in weird places and move about gingerly.

The case for Kramer is more persistent than for any other player not in the Hall of Fame. There’s an internet petition, a scattershot movement on Twitter and Facebook aided in part by the efforts of Alicia, and scores of pro-Kramer letters written annually to the Hall. His case has been the same for more than 40 years: He was a key blocker for Hall of Famers Bart Starr and Jim Taylor. He was the fulcrum of Lombardi’s patented sweep play. He was a first-team All-Pro guard five times and second-team once. He was named one of the two guards on the NFL’s 50th-year anniversary team. (When the 75-year team was selected, the three guards were Jim Parker, Gene Upshaw and John Hannah.) And, of course, there’s the Ice Bowl block, where Kramer led the way on Bart Starr’s quarterback sneak that won the 1967 NFL Championship Game over Dallas at Lambeau Field.

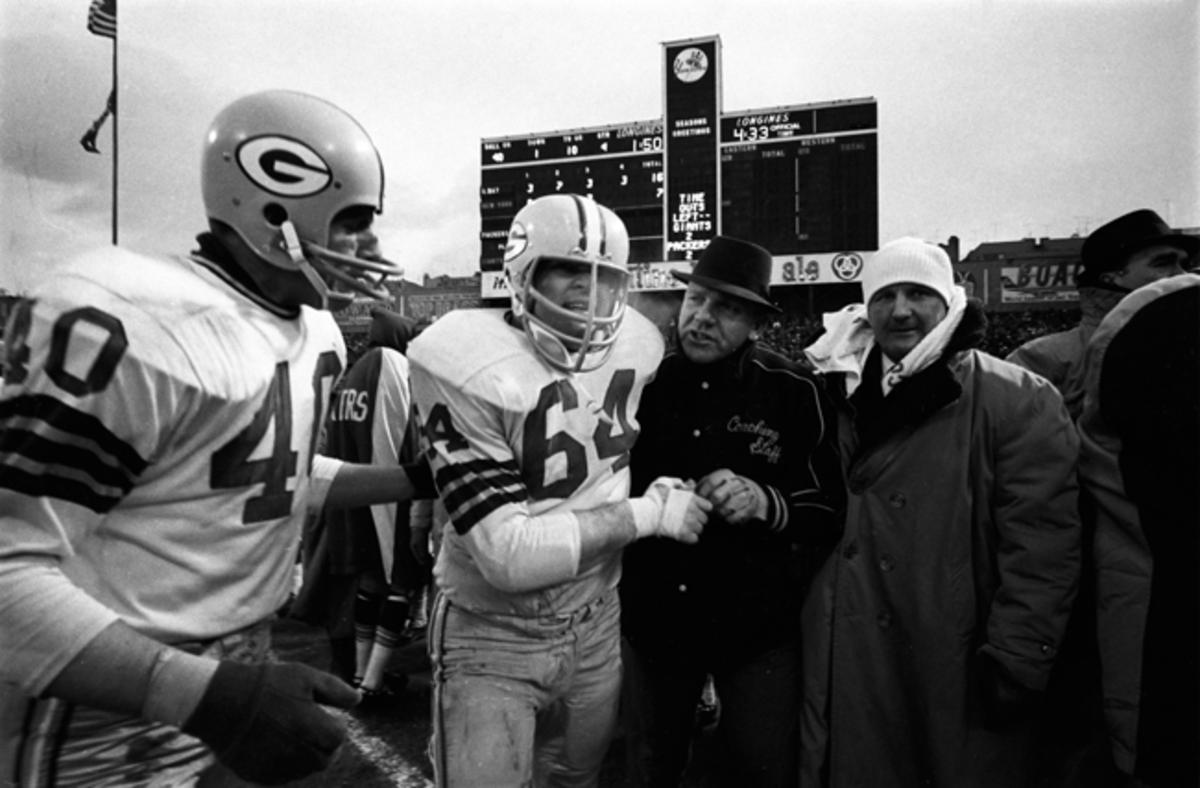

Two little-known details about that block: It came on a play that Kramer himself suggested while watching Cowboys defensive tackle Jethro Pugh on film. Kramer noticed Pugh playing tall on a short-yardage snap and told Lombardi he thought they could wedge-block him. “Wind back the tape,” Lombardi said. After another viewing, the coach concurred. Kramer didn’t know the play would be called in the game’s most critical moment. If he had, he says he may not have had the guts to suggest it. The play went exactly as expected. At the snap, Pugh came up high in his stance and Kramer went low, driving himself into Pugh’s left side and creating a path for Starr.

The other detail is that when Kramer lined up, he felt a divot under his left foot. It fit perfectly, like a starting block. And so Kramer pushed out of his stance with that foot, instead of his right foot. It was the only time in his life—game or practice—that he ever did that.

When watching footage of old Packers games, a keen football observer notices two things. One: Right Guard No. 64 was remarkably nimble, in pass-protection and especially in the run game. But two: Evaluating Right Guard No. 64 as an all-around player on the little existing game film is essentially impossible. If any wide-angle film or any end-zone shots of film from that era exists, it can’t be found. (The Packers' own video department has to rely on YouTube clips at times.) NFL Films has only a few games, and they’re all broadcast copy. Which presents the other issue: broadcasts back then employed only a few cameras, and those featured tight shots on skill players and closely followed the ball. You only see Kramer occasionally flash across the screen; you can’t see anything from the defense he was facing or from the players around him. There’s absolutely no context.

Context would be a problem even if the cameras captured Kramer. Someone who analyzes the NFL now is probably not equipped to analyze the NFL from nearly 60 years ago. The game was so different. Plus, even if you could somehow pinpoint Kramer’s attributes, they’re only relative to those from the rest of the league’s players. The resources (and time) to study the entire 1960s NFL simply doesn’t exist.

* * *

Kramer was a modern-era Hall finalist nine times in 14 years between 1974 and 1987. His modern-era eligibility expired in 1988. Fifteen years after a player’s modern eligibility expires, responsibility for his Hall consideration transfers to the nine-member Senior Committee. Depending on the year, the committee selects one or two players—usually those felt to have slipped between the cracks in their initial eligibility period—to have their cases heard before the full panel of voters. Like the modern-era finalists, a senior finalist must receive 80 percent of the full vote.

Kramer’s only instance as a senior finalist was 1997. There’s no cap on how many chances a player gets. Five others have appeared twice; only one of them, Chicago Cardinals running back Marshall Goldberg, was rejected both times.

So, in total, Kramer’s case was heard 10 times over a 24-year period between 1974 and 1997, and rejected each time.

The popular opinion for why Kramer wasn’t elected is that voters felt that too many members of the 1960s Packers were already in. By 1997 that great Green Bay team had 11 men in Canton, including Lombardi. It’s now up to 12; linebacker Dave Robinson was elected as a Senior candidate in 2013.

Those were the sentiments of voters back then. Twenty years later voters must rely on the previous generation’s opinions. Most of today’s voters feel that senior finalist spots are there to help players whose cases weren’t fully heard during their years of eligibility. That would not include Kramer, whose case was presented nine times before a group that saw the great ’60s Packers often, and then a 10th time in front of a committee with a mix of voters—some who covered him, most of whom didn’t.

Complicating matters is that Kramer is not the only Packer still in Hall of Fame limbo. There’s also fellow offensive lineman Bob Skoronski, Gale Gillingham and Boyd Dowler. In August 2012, Peter King of Sports Illustrated—who is now the editor of this website—spoke to Bart Starr about Dave Robinson’s candidacy, which Starr strongly endorsed. Starr told King there was one other candidate he felt strongly about. “Bob Skoronski,” Starr told King. “Forrest Gregg was great, and he protected me on my front side, at right tackle. Bob protected my blind side at left tackle, and you know how important the blind side is for protection to a quarterback. You'd look at their grades when the coaches graded the film after the game, and their grades were virtually the same, game after game. I am so disappointed he hasn’t gotten in the Hall. Some of the [offensive linemen] who have been selected to the Hall over the years, I'm just aghast. Bob Skoronski is a level above them.”

Then King wrote: Skoronski and Gregg were the bookend tackles on the five Green Bay championship teams. You could hear Starr’s passion for Skoronski—who played 146 games between 1956 and 1968 for the Packers—come through on the phone. I asked Starr if there were other players he wanted to recommend, and he said no.

Voters interpreted this as Starr declining to endorse Kramer.

When asked about Starr’s exchange with King, Kramer says, “Very interesting. I’ve never heard that. And I’m kind of surprised by it. Bart has been one of my pals, I thought, for many, many years. I spoke with him last year at the Bart Starr Breakfast. He couldn’t make it, so he called me and asked me to attend in his place. And I have. Also, I’ve given him the tips on the stem cells to help with his strokes, and his heart attack and all his problems. And when he greets me on the field at the alumni game, he gives me a big hug, wraps his arms around me, and says, ‘How ya doing mister?’ So I’m kind of confused by it. I think probably Bart would have a difficult time explaining that today. And I probably would not ask him to.”

In 2013, Starr had an email correspondence with SB Nation’s Matt Verderame, and this time the Hall of Fame QB included another teammate in the Canton discussion. “Kramer and Skoronski need to be recognized by the Pro Football Hall of Fame,” he wrote. “They held key starting positions for a team who won five NFL titles! Jerry and Bob consistently made the plays that directly contributed to those titles, period. There is not another Hall of Fame player at the position of right guard or left tackle, today or before, who accomplished what Jerry and Bob did. I honestly don’t know what you have to do to be more qualified.” When told of this later exchange, Kramer said, “It’s not really a surprise. Bart was like my family ... you wonder why one person, who made an off comment, maybe a mistake, maybe he forgot, maybe he was off that day, maybe he didn’t think about it. It’s interesting that we’re hanging so much emphasis on that particular moment and that particular comment.”

Skoronski was never a modern-era finalist, and he has not been a Seniors Committee candidate either. Skoronski, Kramer said, “was a hell of a football player and a great friend of mine. If [voters] want to put him on the list ahead of me, that’s OK with me.”

But the Kramer case is not dead. Several members of the Hall of Fame’s 48-member selection committee believe it should be heard again. The 2017 Seniors candidate, former Seattle safety Kenny Easley, was voted in. There will be two Seniors candidates in 2018 (it alternates from one candidate to two each year) and it’s likely the drum will start beating anew for Kramer in advance of the annual Seniors Committee meeting next August.

* * *

Hall of Fame or no Hall of Fame, thanks to a national bestseller, Instant Replay, and a follow-up book, Farewell to Football, plus a speaking circuit that at one point reached 150 appearances a year, Kramer remains the unofficial spokesman of Lombardi’s Packers. In Wisconsin he still encounters waves of adoring fans.

Kramer’s life has been a series of new endeavors. Most of them, like his pro football career, lasted a few years, featured incredible highs and quiet, unceremonious endings. There was the apartment business in Oklahoma. A commercial diving business in Louisiana. Coal mines in Kentucky. Motivational films in Hollywood. Telecommunications in Kansas City.

“I get something going and then I’ll go, ‘What else is going on?’ ” Kramer says. “I had this conversation with myself one day. I said ‘What the hell are you doing? Why do you keep changing businesses?’ Well, there’s a challenge to it.”

Kramer has been many things, but to most, he remains simply the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s biggest snub. To those who know he’s a snub, anyway.

Kramer says Roger Goodell once asked him why he never attends the annual Hall of Fame ceremonies. Kramer told him because he’s not in the Hall of Fame. He said the commissioner was astonished.

The exchange with Goodell was nothing new. As Alicia tells it, “Every time we’d go to an appearance, they would either refer to Dad as a Hall of Famer, or they’d ask about it. It was kind of interesting to watch. Dad would try to correct them—‘I’m not in the Hall of Fame’—and there’d always be that conversation.”

“That awkward moment,” Kramer interjects. “I’m not really in the Hall of Fame. ‘Well how come?’ So I just quit saying I wasn’t in the Hall, just to avoid all the follow-up bullshit.” He smiles.

This past August, Kramer even avoided the monster-sized Packers party that rolled into Canton for Brett Favre’s enshrinement. “I just don’t feel comfortable there,” Kramer says of Canton. “I feel like I’d be prospecting or recruiting or trying to wave my flag.”

At Kramer’s personal appearances, patrons would approach Alicia and encourage her to campaign for her father’s enshrinement. Already passionate about perusing Kramer’s old memorabilia and press clippings, she started sharing her findings online and quickly built a network of fans. From this came a public Hall of Fame campaign unparalleled in vigor and volume. Joe Horrigan, vice president of the hall, has said that 25 percent of the mail he receives is about Kramer. Some voters have even started referring to the campaign as a crusade.

But it’s not just family, friends and fans hoisting megaphones. More than 40 former NFL players, including 34 Hall of Famers, have endorsed Kramer. It started informally with Sam Huff in ’97. The former linebacking great, inducted in 1982, went around and collected seven other letters of recommendation.

“The names on that list are validation if you need it without the other [accolades],” Kramer says. “It’s really comforting for me to have Merlin Olsen and Alex Karras and those kind of guys write notes.”

Many of the other letters came from Alicia and a marketing company that worked pro bono for Kramer reaching out to former teammates and opponents in 2014. Today, the campaign is slowing—Alicia keeps a lot of other balls in the air—but endorsements still come in. The most recent were from Warren Moon and Donald Driver, via Twitter.

When asked point-blank why he thinks he’s not in the Hall, Kramer struggles to find an explanation. Huff once offered to ask around and find out. The search yielded little more than speculation about Green Bay’s voter reps. (Each team has a person on the Hall voting committee charged with representing players from that team.) Kramer remembers a post-practice “pissing contest” he once got into with Green Bay writer and voter Art Daley, though Kramer later apologized and came away confident that everything was straightened out. (Daley has since endorsed Kramer.) He wonders if the attention from his books rubbed some voters the wrong way but can’t imagine how.

Of course, all of this pertains to those past voters. If Kramer is ever selected, it will be by a new generation that never saw him play. If voters who did see him said no, why should voters who didn’t see him say yes?

“Well, the same people [who rejected me originally] voted me on the All-Time 50-Year Team,” Kramer says. “And they voted me one of the top 10 Packers of all time, or top 3 Packers or whatever—I’m not sure of all of this stuff.” He also cites the All-Time Super Bowl team that was announced last year, for which he was one of the guards. “If they know me enough to elect me the All-Time Super Bowl team, it’d seem like they’d know enough to put me in the Hall. But maybe they just don’t feel like I played that well. Or maybe they’re aggravated at me for something I don’t know about.”

There’s no hint of bitterness when Kramer says this, though you sense maybe there used to be. He talks about the Hall only when asked, and he constantly circles back to his disbelief and gratitude for all that football has brought him.

“If you take me back to Sandpoint High and tell me I’m going to be the top guard in the first 50 years of football, All-Pro, All-Everything, five world championships, I’m gonna say, ‘Yeah, out of a pig’s ass. I’m gonna be skidding lumber up in Montana, that’s what I’ll be doing.’ You couldn’t dream this.”

There’s also the irony that many of his life opportunities have come about because he’s not in Canton. When you’re known as the biggest living Hall of Fame snub, and maybe the biggest snub in history, you develop somewhat of a cult following. The last player regarded as a snub on Kramer’s scale was Art Monk. And how often have you heard his name since he was enshrined in 2008?

This isn’t lost on Kramer.

“[My son] and I were talking one day 10 years ago and he said, ‘Dad, you selected fame instead of the Hall of Fame, didn’t you?’ I said not really, I didn’t select anything, it just worked out that way. He said, ‘You’re better known now than if you had been in the Hall.’ I said there might be something to that.”

Question? Comment? Story idea? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com