On Epic NFL Collapses, the Oilers Can Tell the Falcons a Thing or Two

HOUSTON — As Super Bowl 51 kicked off at NRG Stadium last month, about 25 former Houston Oilers gathered a mile and a half away at the Coaches Corner, a sports bar owned by Haywood Jeffires, the former Oilers Pro Bowl receiver. The players congregated in a back area, eating chicken wings and drinking, carrying on and watching the game. Some of them lived in the area, some had come in for the game, and some of them hadn’t seen each other in years. Houston’s hosting of the Super Bowl had given the former Oilers a reason to return, and the week had become one long reunion. They’d been attending parties all week, catching up, swapping stories and reminiscing.

In the Coaches Corner now, everywhere they looked there seemed to be another framed baby-blue jersey: Warren Moon, Ernest Givins, Drew Hill, Curtis Duncan, Lorenzo White, Jeffires. The place is unequivocally an Oilers bar, a shrine to the Run-and-Shoot offense, to the franchise’s glory years of the late ’80s and early ’90s, when the Oilers made the playoffs seven consecutive seasons. Some of the stars on those teams were here now to watch the game.

They looked on as the Falcons jumped out to a 28-3 lead over the Patriots in the third quarter. Matt Ryan, Julio Jones and Atlanta’s high-powered offense looked unstoppable, moving up and down the field with ease—like Moon and Jeffires and those old Run-and-Shoot teams. And then Tom Brady and the Patriots scored, and New England began slowly, methodically mounting a comeback, pulling closer and closer.

Those old Oilers got anxious, watching the game unfold from their bar stools. They bantered back and forth with one another, critiquing the Falcons’ play-calling. Their defense has been on the field too long! They look gassed. Why aren’t they running the ball and milking the clock?

The Falcons were blowing a 25-point lead: 28-12 … 28-20 … 28-28.

Unbeknownst to one another, several Oilers at the bar started having flashbacks. The same flashback. January 1993—the Buffalo Game. Houston held a 35-3 lead over the Bills in the third quarter of their wild-card playoff, in a season in which the Oilers were expecting to win the Super Bowl. What happened next was historic.

The Oilers collapsed and lost, 41-38, in overtime. It’s still the largest blown lead ever in the postseason. Those Oilers players knew, perhaps better than anyone else in the world, what the Falcons were experiencing.

The Falcons are not about to do what I think they’re going to do, are they? Bubba McDowell, a cornerback on that Oilers team, asked himself. But he did not dare say it out loud. Not in a bar full of Houston Oilers. He decided it was best to keep quiet.

* * *

Why are we making this so hard on ourselves?

That’s what Warren Moon kept asking himself, as the Oilers’ lead against the Bills slipped away that January day in Buffalo. This was Houston’s year, Moon thought. The Oilers had been competitive for the last few seasons and were finally poised to make a deep playoff run. Playing out of coach Jack Pardee’s Run-and-Shoot, they had the most prolific passing attack in the NFL. Houston also had the league’s third-ranked defense. Nine Oilers made the Pro Bowl that season, including seven on offense—future Hall of Fame linemen Bruce Matthews and Mike Munchak; White, the running back; receivers Jeffires, Givins and Duncan; and Moon, their future Hall of Fame quarterback.

The Oilers had throttled the Bills 27-3 in the regular-season finale. And in the wild-card game, by the time Houston had scored their fifth touchdown early in the third quarter, the Bills had lost two top offensive weapons, quarterback Jim Kelly and running back Thurman Thomas, to injuries.

“I never thought we were going to lose,” Moon says now.

Then after going up 35-3, Oilers kicker Al Del Greco miss-hit the ensuing kickoff, giving the Bills the ball at midfield, which led to a Buffalo touchdown … then the Bills recovered an onside kick and scored again. … then the Bills forced a three-and-out and scored again. The Oilers had the ball and another chance to stop the bleeding, when … the Bills picked off Moon and scored yet again.

“We just couldn’t stop the madness,” Jeffires says. “You wanted this to be over. It was almost like a dream.”

Or, more accurately, a nightmare.

Entering the fourth quarter, the Oilers only led by four, 35-31. Moon and the Houston offense regained their composure long enough to string together a long drive, deep into Bills territory. But when it stalled and they settled for a field-goal attempt, Greg Montgomery, the holder, fumbled the snap, and the Oilers didn’t get the kick off.

“Absolutely nothing was going right,” says McDowell, the cornerback. “We just had mistake after mistake after mistake after mistake. It was just piling up. There was no end. I was like, how bad can we screw this up?”

“There was a lot of arguing on the plane home. Pointing fingers. Everyone was just jawing at each other. We’d messed up a golden opportunity.”

The Oilers already had some history of blowing late leads. The previous year, in the divisional round of the playoffs, they were ahead of Denver 24-16 in the fourth quarter when John Elway engineered two drives that resulted in 10 points and a Broncos win.

This was worse. The Oilers weren’t playing Elway or Kelly. This was Kelly’s longtime backup, Frank Reich, burning them. With about three minutes left in the fourth quarter Reich threw his thirdconsecutive touchdown to Andre Reed, and the Bills had their first lead. They had scored 35 unanswered points in less than two quarters. Bills 38, Oilers 35.

Moon had one more comeback in him. He led a drive that produced a field goal to force overtime. The Oilers even won the toss in overtime, too. But on the opening drive Moon threw another pick (helped by a missed holding penalty on Buffalo), and a face-mask call on the runback gave the Bills the ball in field-goal range. Game over. Bills 41, Oilers 38.

“There was a lot of arguing among the players on the bus, on the plane home,” says Givins, one of the Pro Bowl receivers. “Shaking our heads. Pointing fingers. Arguing with each other. Could’ve, would’ve, should’ve—that type of thing. We should’ve made some adjustments, this and that. Everyone was just jawing at each other. … [We had] messed up a golden opportunity. … We win that game, we win the Super Bowl—no question.”

* * *

In the offseason, the Oilers went their separate ways. Some left for vacation, some returned to their hometowns. Anywhere they could clear their heads, forget about the game and hopefully avoid the people constantly approaching them, asking about the collapse.

“Probably didn’t leave my house for a week,” Moon says.

At one point Moon and the other team leaders gathered and discussed their collective mindset heading into the 1993 season. “We said, are we going to let last year destroy us?” Moon recalls. “Everybody thinks that’s going to destroy us, so how are we going to handle that? The faster we can get that out of our mind—that happened last year, but this is a new football team. … We were trying to get everyone to buy in, that this isn’t the same team, this is a different team, the ’93 team. That was the ’92 team. We had a new defensive coordinator, Buddy Ryan. It was a different atmosphere. We had to keep selling everyone on that.”

The sales job didn’t work, at first. Houston lost four of its first five games, the last of which was a 35-7 rout in Buffalo. “We were still in shock,” Givins says. Even Moon admits the collapse had “lingered a little bit.”

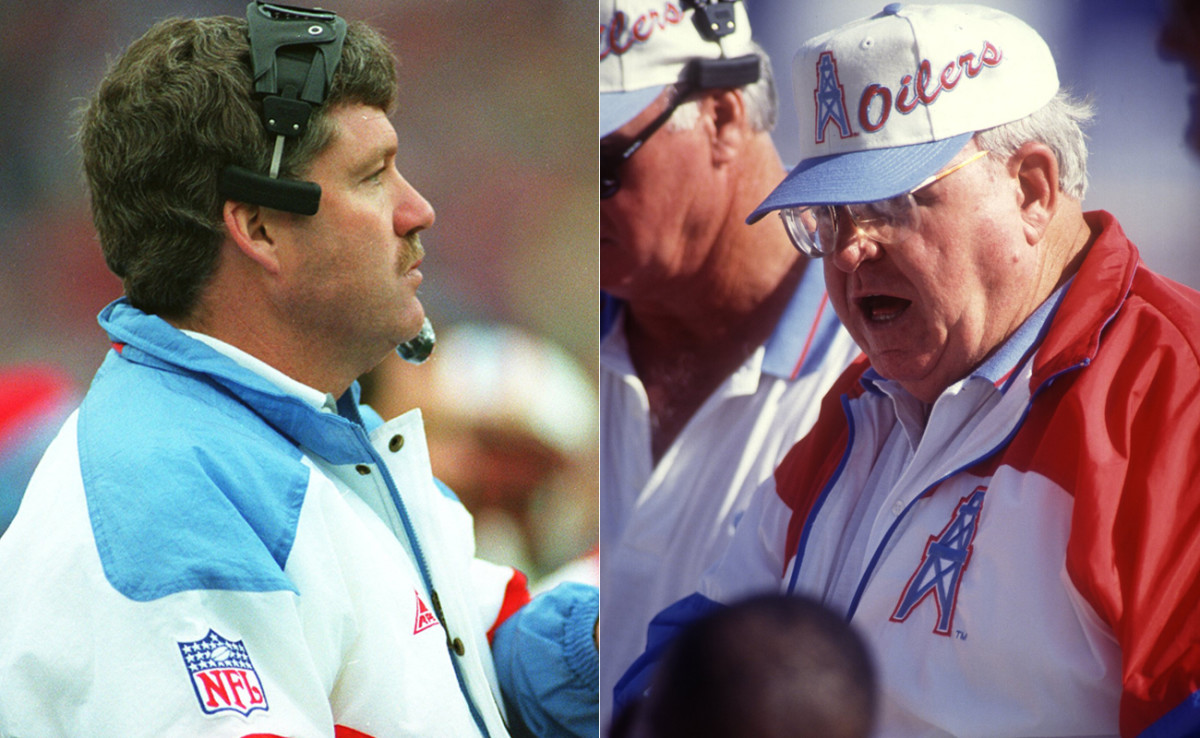

As if the playoff collapse weren’t enough to overcome, the 1993 Oilers had a series of tumultuous incidents to deal with over the course of the season. Offensive lineman David Williams missed a game because his wife was in labor, and the team fined him, sparking a national outcry; the episode became known as “Babygate.” Reserve defensive lineman Jeff Alm committed suicide after his friend died in an automobile accident in which Alm was driving; Alm’s blood-alcohol content was above the legal limit. And when Buddy Ryan’s dissatisfaction with what he called the “Chuck-and-Duck” boiled over, he and offensive Kevin Gilbride got into a heated exchange, culminating in Ryan slugging Gilbride in the face. NFL Films later made a documentary based entirely on the Oilers’ dysfunctional 1993 season.

On top of all that, midway through the season Bud Adams, the owner, threatened to dismantle the team if it didn’t win the Super Bowl. The NFL would be instituting a salary cap for the first time in 1994, and it would be more difficult to hang on to all those Pro Bowlers—or to justify doing so, especially if they failed in the playoffs again.

After the 1-4 start, Oilers coaches decided to bench Moon for the next game, against the Patriots, hoping the move would jump-start the team. In a way it did. Cody Carlson, Moon’s backup, was injured during the game, and Moon returned to the field inspired. Houston beat New England, 28-14, then promptly ripped off 10 more consecutive wins, despite all the turmoil. “We said, let’s just forget about it and play carefree football,” Givins says.

The Oilers earned the No. 2 seed in the AFC, which meant they would face Joe Montana and the No. 3-seeded Chiefs in the divisional round. Houston held a 13-7 lead early in the fourth quarter of that game, too. Then Montana led three more touchdown drives, including one in the waning moments that sealed a 28-20 win. “It was a controversial, emotional year for us,” Moon says. “By the end, after everything we went through, we were running on empty. We didn’t have enough to win that playoff game. Then Joe Montana worked his magic.”

* * *

Adams, of course, followed through on his threat. After the Chiefs loss, the Oilers traded Moon to the Vikings and Buddy Ryan left to coach the Cardinals. Houston went 2-14 in 1994, and Pardee resigned by midseason. Two years later, after the city refused to finance the stadium he wanted, Adams moved the team to Tennessee.

If the Oilers had won a Super Bowl, would Adams have stayed? Who knows. One can argue, though, that the playoff collapse against the Bills set in motion this entire chain of events. Blowing that 32-point lead may have been the beginning of the end of the Houston Oilers.

“Wounds heal,” says Jeffires, “but you never forget.”

Now, 24 years later, the Oilers are still asked about that game. They were asked about it all week leading up to Super Bowl 51, even before the Falcons blew that 25-point lead and set their own record—largest collapse in a Super Bowl. People are still naturally curious: How does a team fall apart like that? Players invariably respond saying something about failing to finish, not executing. But the truth is, they don’t really have an explanation.

“It leaves a big hole in your heart, you know?” Jeffires says on the phone, a few weeks after watching the Falcons’ collapse. “They say things do pass. Like, when someone dies in your family? You think you’re never going to get over it. Then sooner or later, you do. Wounds heal. But you never forget. That game will be a dagger in our hearts for as long as we live.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.