Growing Old After Football

This week, The MMQB published two stories about stars on the Dolphins’ 1972 undefeated team—linebacker Nick Buoniconti, who has been diagnosed with neurodegenerative dementia, and running back Jim Kiick, who recently moved into an assisted living facility because of dementia and Alzheimer’s. Though chronic traumatic encephalopathy can only be diagnosed after death, players are thought to be suffering from the degenerative brain disease.

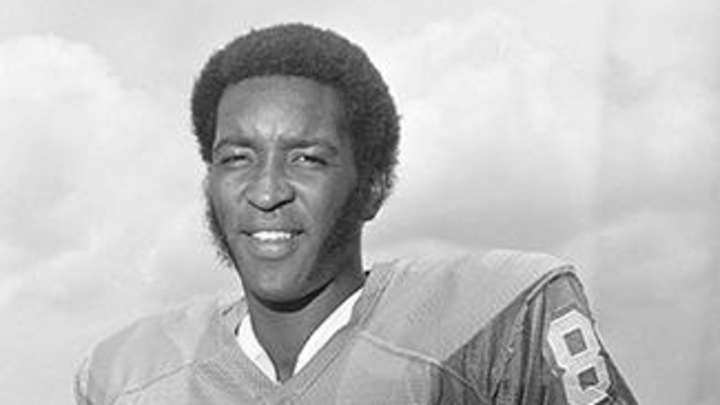

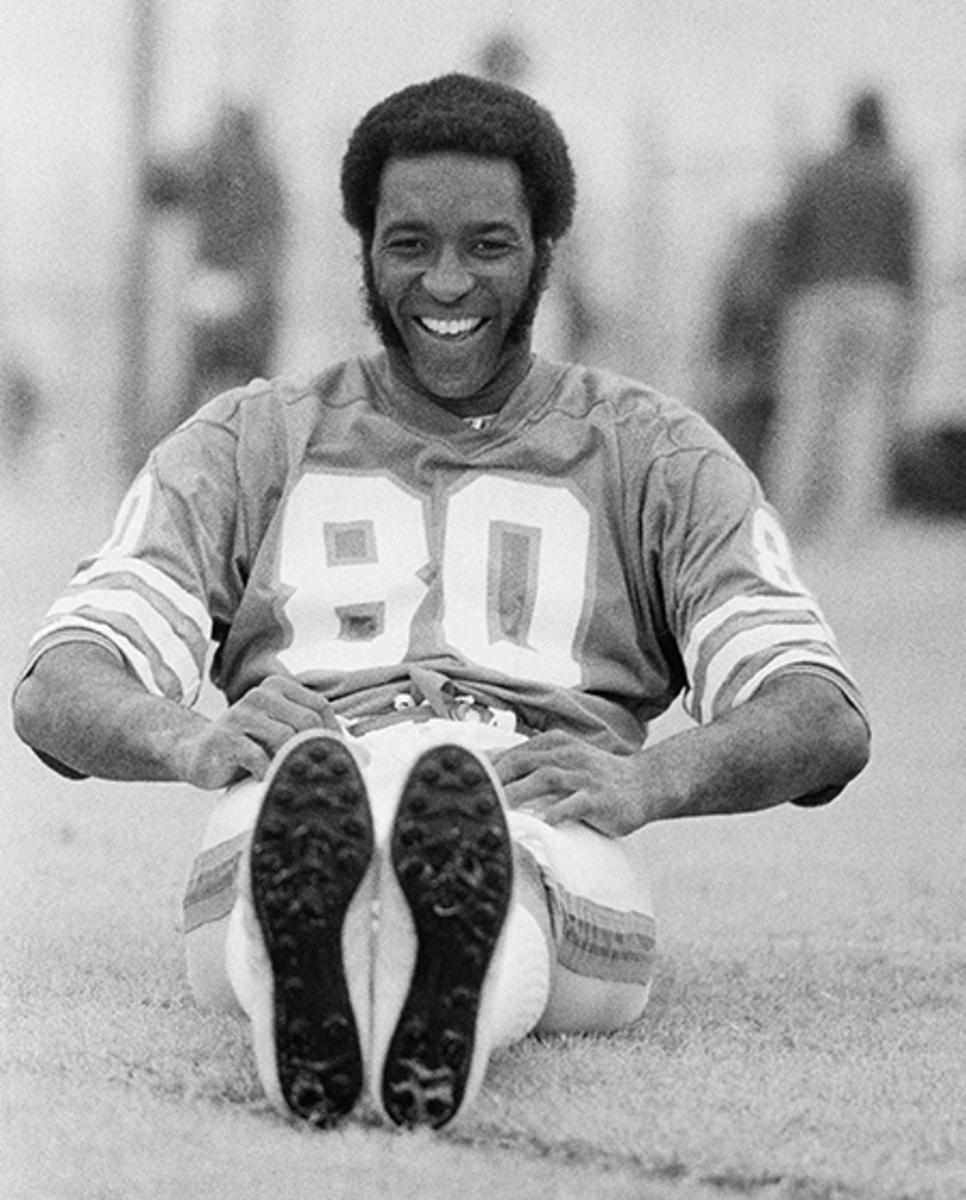

For this week’s Talking Football, we reached out to Marv Fleming and Howard Twilley, who also played on the Dolphins’ undefeated team. Fleming, a tight end, is 75 now and living in Marina Del Rey, Calif. He’s retired from a career in real estate that he began after football. Twilley, a receiver, is 73 and living in Dallas. He’s retired after working in a footwear business and working in wealth management.

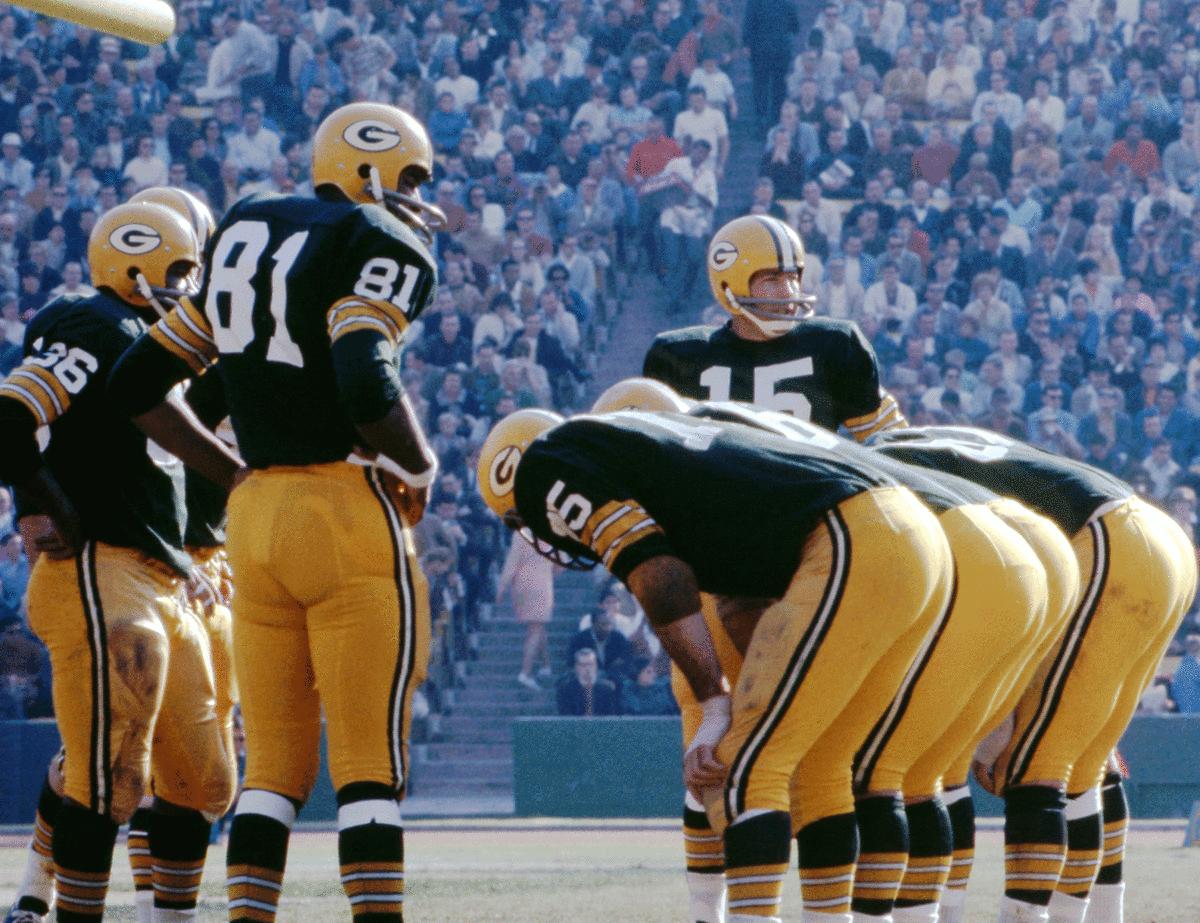

Both players won two Super Bowls with the Dolphins, and Fleming also won two Super Bowls and an NFL title playing in Green Bay prior to joining Miami. Fleming and Twilley both have been tested for brain damage, and they say their results are clear. But they’re also aware of the declining health of some teammates. We spoke to them about what life is like for retired players who is mentally strong and healthy, how the league treats its former players, and whether or not they’d play football again knowing the damage that football can cause.

KAHLER: What is it like to witness the decline of your teammates, Nick Buoniconti and Jim Kiick?

FLEMING: Years ago, I was the founder and president of the 1972 Perfect Season team. I’m the one who started it and got players to do signings and reunions . . . My mom had Alzheimers, and so I see it a lot. Mainly because I was on another team for seven years prior to the Dolphins, at the Green Bay Packers, and there, I see it a lot more. You know that look you sometimes see from your grandparents where they have their eyes open really big like they are trying to process what you are saying? Every year we have an Ice Bowl team reunion in Green Bay and I see it more and more and more. Out of the roster, I’d go so far to say there are at least 15 or 20 that need help. I read a story where one player from that team went for a walk and they found him two days later and he was underneath a bridge. They said, where have you been, what are you doing? And he says, well I got tired of walking, walking, walking. With the Dolphins, there have been several instances where I can look at a guy and tell right off just by me talking to them and the way they respond that they have slowed down quite a bit.

TWILLEY: Most of the times you just don’t want to bring it up. I’ve noticed Nick—the last time I saw Nick was at the 50-year reunion of the NFL and the 50-year reunion of the Miami Dolphins, that was last year. My wife and I went to Miami and I did see him there and he seemed to be a little glossy-eyed. He didn’t seem to be as sharp, but I didn’t think anything of it. I thought he was just getting old and so am I . . . I wasn’t going to go up and say, Gee, you look terrible, Nick, do you have dementia? I don’t live in Miami, so I didn’t know about the details. In fact, I had no idea about Jim Kiick. I did believe that Jim had some issues, but believing and knowing are not the same thing. It’s really something that we’re all aware of . . .

FLEMING: Two years ago we had a signing in Chicago, and when you see guys, you are happy to see them, you shake hands and all that, and I saw Jim Kiick and I knew right away . . . I’m not going to list them all, but there are a few players on the team that have the beginnings of it.

KAHLER: Are there any other teammates that you noticed aren’t doing well?

TWILLEY: I went to [quarterback] Earl Morrall’s funeral. It doesn’t surprise me [that he had CTE], because he played a long time and he got a lot of hits. He was a great friend. We have these reunions from time to time and I guess I saw Earl at the 40th reunion, and his arm was shaking, and I thought to myself, Well, he was probably 87 at the time. I really loved Earl. Solid guy. We all diminish as we get older. Nobody gets out of this world alive . . . I’ve seen Hubert Ginn, he was a special-teams player, he was a reserve defensive back and he returned kickoffs and punts. He has a person with him all the time, someone who is paid to watch after him.

KAHLER: Along with the stories of Buoniconti and Kiick, other members of the 1972 team have also been affected by CTE. Morrall died in April 2014 and was found to stage four CTE. Defensive end Bill Stanfill died in November after a long battle with dementia, and his brain and spine were sent to Boston University's CTE center. Knowing that, are you scared for your own future?

TWILLEY: Absolutely, I am concerned about it. There are things that you can have some control over and there are a lot more things that you have no control over, and that’s one of them. If you’ve gone through it and you hit people a lot and your body makeup and personality are such that it is going to happen to you, it is going to happen to you and there’s not a whole lot you can do about it. I don’t know whether that will ever happen to me, and certainly I am not stupid enough to think that I’m immune from it. There is a level of concern moving to a level of fear. Some concern is there for everybody and then there is the, I’m going to get it, I’m unlucky, and I don’t think you can say that because I don’t think anybody knows that.

FLEMING: I am always thinking about it. I think about it a lot. I know it’s going to happen, and being 75 years old, I am glad I’ve gotten to be this age. I’m hoping that I can go longer. I am still skateboarding, I live near Venice Beach, so I still skateboard. I stopped skiing, because that really put myself in harm’s way. I am trying to be active. I still have a Vespa scooter for the beach. I’m still so far, so good, I’ve got my fingers crossed and I am trying to do the right thing.

KAHLER: Knowing what you know now—and having seen your former teammates struggle later in life—would you play football again?

FLEMING: Knowing what I know now, I would really look at it hard. Because for those people who want to be football players, there are other things that you can get happy about, you know? I play golf with all these guys who want to play golf with me and want to know about how it is when you run on the field, how it feels when you score a touchdown. These guys pay me to ask these questions, and I’m saying, Hey, there are other things you can have fun with and it doesn’t have to be where it breaks down your body and your brain and curtails your life. I would really look closely at it before I do it again.

TWILLEY: Absolutely, I would play again. I would like to have been paid a little bit more. Fortunately, I went out and got into business and I’ve been financially fine. I wouldn’t trade the experience of catching a pass in the Super Bowl for 10 million dollars or 20 million dollars. I might, but I don't think I would.

FLEMING: I think football is good for a little kid growing up. It teaches him that your little owies, you can live with owies. But once those little owies get big, I don’t think that’s good. You may get scraped and bruised when you are a kid growing up, and I think after high school football, it becomes a business. High school, it’s fun to play it, but when you get to college and the pros, it’s a job. There are more jobs outside football than there are playing professional football, so I would have my kid prepare himself to do something else besides football. I don’t have any children, but if I did, I would have them prepare themselves to do something else besides playing football.

KAHLER: How are you feeling today, mentally?

FLEMING: At the age of 75, we sometimes put our keys down, and where do we put our keys? Oh yes, where I left them. I would like to say that I am testing myself all the time. I do all kinds of word puzzles and I do things to test my memory all the time so that it won’t grow old, and to keep a fresh mind. I play golf probably three times a week. I didn’t drink and I didn’t smoke and I didn’t do drugs or any of that stuff. I wanted to keep my body, especially when I played football, I wanted to have my body just completely ready for the game. I always want to keep myself in good shape. I’ve done the right thing, whatever that was at the time. I’d like to think I’m in pretty good shape.

TWILLEY: Things are going pretty well for me, other than just being forgetful. There is a difference between having dementia and being old and just misplacing things from time to time. I’m retired and I spend time with my grandkids. My job is pretty much doing the yard work. I like to plant flowers and I’m involved with my investments.

FLEMING: I was a tight end, I’d catch the ball and get hit upside the head. I blocked with my head and shoulders. And so, I’m so happy that I feel the way I do now. On a scale of 1-10, I’d say Marv Fleming is a good 8.

KAHLER: Have you been tested for any brain damage?

TWILLEY: I have actually gone to a doctor that the NFL-sponsored and he put me through a test, this was about three or four years ago, and he said, You’re getting old and you are going to forget things, but you don’t have dementia. Whether that is a definitive diagnosis, I’m not sure, but right now I am pretty involved in things. I think about things. I wrote my autobiography, not to publish, but for my kids to understand a little bit more about my life. In terms of dementia, I don’t think I have any of it right now. Now, that doesn’t mean that tomorrow I won’t. I guess you just don’t know.

FLEMING: Yeah, about five years ago, when the concussion thing first came out, I didn’t think I had any problem, so I go to the doctor and I get my head scan and he says, “Wow.” And I said, “Wow, what?” And he says to his assistant, “George, did you see this?” And from the back room, I don’t see his face, I hear, “Yep.” He says, “Come here Marv, look at this.” And on the scan he showed me, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven. Seven patches of dead cells on your brain. I said, “You’re kidding me. There’s nothing wrong with me doctor.” He says, “Marvin, have you ever driven into San Francisco and ran into fog?” I said, yeah. You have to do that on the coast, you know. He says, “That’s going to happen to you one of these days, you’re going to go in and you can’t come out.” Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. I can quote you scriptures and I can tell you all my passwords, I can do this and I can do that.

KAHLER: Did you try any treatment or therapy to be proactive against future brain damage or Marv, in your case, to try to repair the damage you already had?

TWILLEY: No, I didn’t. I have this therapy called planting flowers and reading a Wall Street Journal. I don’t worry about it very much. I worry about it some, but I think being involved and trying to do analytical work as opposed to just playing golf all the time can help. I think that has something to do with my situation. I think if you are using your brain to write things, and to analyze things, I think that helps diminish the possibilities of dementia, but I didn’t go to medical school.

FLEMING: I do what is called hyperbaric oxygen. I really like it. I do it once a week now. I used to do it three times a week. I put in over 400, maybe, close to 400 sessions. I was introduced to hyperbarics after my doctor found the dark spots, the abnormalities, on my scans. I went in for three months. I took my cognitive test before and at the end I took it again—and my scores just jumped off the page, they were so good and so high. I go back in and my doctor says, “Wow, Marvin.” And he says, “George did you see this?” I still never saw George’s face. He says, “Come here Marv, look at this. This is before, and this is after.” I said, “The after is mine too? Where are the spots?” He says, “They all went away, they dissipated. And I said, you’re kidding me. What is going to happen to me now?” He says, “Well, nothing. Probably you’ll get hit by a truck on your cell phone.” I tell everybody about hyperbarics. I tell all my teammates. When you hear Joe Namath does it, I’m the one who introduced Namath to it. I do it to stay afloat and above water. I tell all my teammates and most of them are waiting for the settlement [money]. You see, one thing about hyperbarics, is it’s not insured, but you can still work something out with somebody, like I did. It makes me feel really, really good. It’s 100 percent oxygen. If you have any ailments in your body, it heals it.

• PETER KING'S MAILBAG: The NFL’s Brutal Past Could Cost the League its Future.

KAHLER: What made you decide to get checked out?

TWILLEY: There were a lot of people getting that kind of stuff and dementia was an outcome—and I just wanted to go for my own health. I got it set up with the NFL; it was a doctor in St. Louis. I went there and he did a little test. I really thought the NFL was going take care of all the expenses. The expenses weren’t really too much, I drove there to St. Louis, I took a little test and then he gave me another test. It’s really interesting how those things go because it deals with your ability to focus and remember things. He’ll say, I want you to remember this sentence, and then he will ask you questions about other things and then eventually he’ll say, OK, tell me the magic word or whatever he wanted you to remember. I thought it was pretty good and they had all this stuff about dementia and I went to see the movie, Concussion. I don’t really believe I have any of those things. I had a couple of concussions in the 11 years that I played. But at this point in time, I think some of it has to do with keeping your mind active. Working on analysis, and that’s one of the things I love to read about, what’s going to happen in the stock market. I read The Wall Street Journal everyday.

KAHLER: Howard, did the NFL ever end up paying for your tests?

TWILLEY: It was less than a hundred dollars, so I didn’t worry about it. I probably got confused, but I thought it was well worth the time. I enjoyed meeting the guy, I think he was doing some research on it as well. I got the information from the NFL. The doctor’s name was listed in an NFL correspondence to me and other NFL players.

KAHLER: Did you have any concussions during your career? What do you remember about them?

TWILLEY: It’s called getting your bell rung, but what that means is you get knocked out. I remember we were playing the Boston Patriots, the Boston Patriots in an exhibition game in Memphis, and I think somebody intercepted a pass and then I was trying to make a tackle. I dove at the guy and hit his knee and it knocked me out. I remember that one, I think that was my second year, 1967. And then we were playing an exhibition game against the Eagles in Miami, in 1968, and I was running as hard as I could to catch a guy who intercepted a pass—we threw a few interceptions in those days—and a big defensive end, he blindsided me and he almost knocked me into the stands at The Joe. It was the hardest I’ve ever been hit in football. I was out for a little while.

FLEMING: I did get hit one time and knocked out. I tell a story that when I woke up laying on my back, you see the trainer, the doctor, you see some players, you see your mom, your dad, your brothers, you see the insurance people, you see the banks, you see the guy you say you’re going to owe money to. Everybody wants to know, are you going to be all right? I’m kidding about all those people, but that’s how people are looking at you, are you going to be all right? I only had one instance like that that I can recall. I was laying there and they gave me some smelling salts and I walked off the field. I had a pretty successful non-big injury playing career.

KAHLER: Jim Kiick filed in the NFL concussion settlement and might receive some kind of payout. Did you register in that settlement?

TWILLEY: I don’t have a qualifying diagnosis at this point. I haven’t filed for any payment but I have registered and that means if something happens to me later, I’ve at least registered my experience to reserve my right to take the settlement if something happens to me later. It depends on what you have, if you have Lou Gehrig’s disease, you get a lot of money but you don’t live very long. I really haven’t worried too much about that, because I don’t want any of that settlement, because I don’t want to get sick.

FLEMING: I went and did my baseline testing and I won’t be getting anything, which I am glad. I didn’t have any qualifying diagnosis. I didn’t have anything that would cause for any payment.

“Please write this: The NFL is great for distractions. They distract the public and make the public think they are doing things for the players.”

KAHLER: How much money was your first contract worth?

FLEMING: A whopping $15,000. And I got a $5,000 bonus.

TWILLEY: I signed for $25,000 per year and negotiated for different things. From time to time when I was playing, there would be a new league, the World Football League or the USFL, and those things would help because competition always helps in a capitalistic society. I got paid a little bit more because of some of that kind of stuff. The most money that I ever made playing football was $80,000 a year.

FLEMING: Outside football, I made more money there. I can tell you this, I used to get a pension check for $143.46 a month from the NFL. Then they had the strike four or five years ago that upped it, because the NFL was getting sued and they wanted to do some good to the players, so they gave us a legacy check, and the amount of years you played, they upped that. So you saw how much I was getting before, $143.46, now I am getting $30,000 per year. So don’t feel sorry for me, OK, remember I did real estate and I made more money in real estate than anything. Residential real estate, buying and selling homes.

TWILLEY: My pension comes out to about $46,000 a year. And that’s for 11 years. If you played less than 11 years you get less. And that is also the new legacy benefit, when they had the last lawsuit or last labor fight, they said well, we need to take care some of these old veterans who didn’t get paid very much. I think my NFL retirement before the increase was about $33,000, so it was a pretty big increase. It’s like you said before, would I do it differently? No, I wouldn’t do it differently. I was fortunate to be signed right out of the University of Tulsa with a guaranteed contract. The Dolphins didn’t have that much money to begin with, Joe Robbie did a real good job of making that into a fortune, and he didn’t have a fortune at the time. I remember guys going to the bank with their checks because they were afraid it wouldn’t [clear if they waited].

KAHLER: What do you think of the settlement? Are you frustrated? Are your former teammates frustrated?

FLEMING: Yeah they are. The NFL is all about money—money that they don’t want to pay. They have to pay the players that are playing, because they are making the money, but they really don’t care how they got there, meaning they don’t care about the former players. If they can block them out, they would. We are a thing of the past. It’s not that they care anymore, but they’ve moved on and it seems like to me that they should take care of the people who are taking care of them. I’m talking about the owners and the young ball players. In basketball, they upped the pension for the guys that didn’t get paid very much. This happened with their new CBA. I read about it and thought, Wow, football people should look at that and give us a little bit more money to live on. The guys that played when I played, we made a little money for that time, but it’s nothing compared to what it is today. It’s nothing.

TWILLEY: I think the NFL is in it to make money. I don’t want to give them too much credit, because they were sued. They didn’t come out and offer and say, Hey, we are going to give you guys all this money. They were made to give you the money of the settlement by the court. I’m not trying to be hard on the NFL, too, these guys are businessmen . . . I don’t know if this settlement is the end-all, be-all. I’m not a lawyer and I don’t know any of those kinds of things, but when you are working in a very precarious industry and all the risks are not explained to you, I don’t know how much that is worth. I’m not saying that the NFL settlement is bad. I think it is good, but I don’t know if it is adequate.

KAHLER: Do you have any anger toward the NFL about the treatment of retired players?

FLEMING: I am angry at them for not sharing the wealth with the older guys who brought the game to where it is today. I am angry at them not sharing. That’s what I am angry at. As far as going into the game, I knew that you could get hurt. I knew that. But as big as the game is today, yes, I am angry at them not being helpful to the players, because we have players living in trailers, we have players on the street, we have players who don’t have anything. And these are the guys who didn’t plan for it, but they are part of that fraternity that is supposed to be so great and all that stuff, they should be taken care of. You can write this, please write this: The NFL is great for distractions. They distract the public and make the public think they are doing things for the players. They are great for distractions. We’re doing this and we’re doing this, and we’re doing that. But if you go to those places and see how many players are participating in their programs, you’d be surprised that not many players are doing it. They are great for distractions and they just want to—there’s that old saying, deny until they die . . . Yes, I am angry, but it is a business and they can do what they want and I’m taking my little notoriety that I have and I’m using it and so far I am doing very, very good. Financially and emotionally and everything else.

Question? Comment? Story idea? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com