Analytics and the NFL: Finding Strength in Numbers

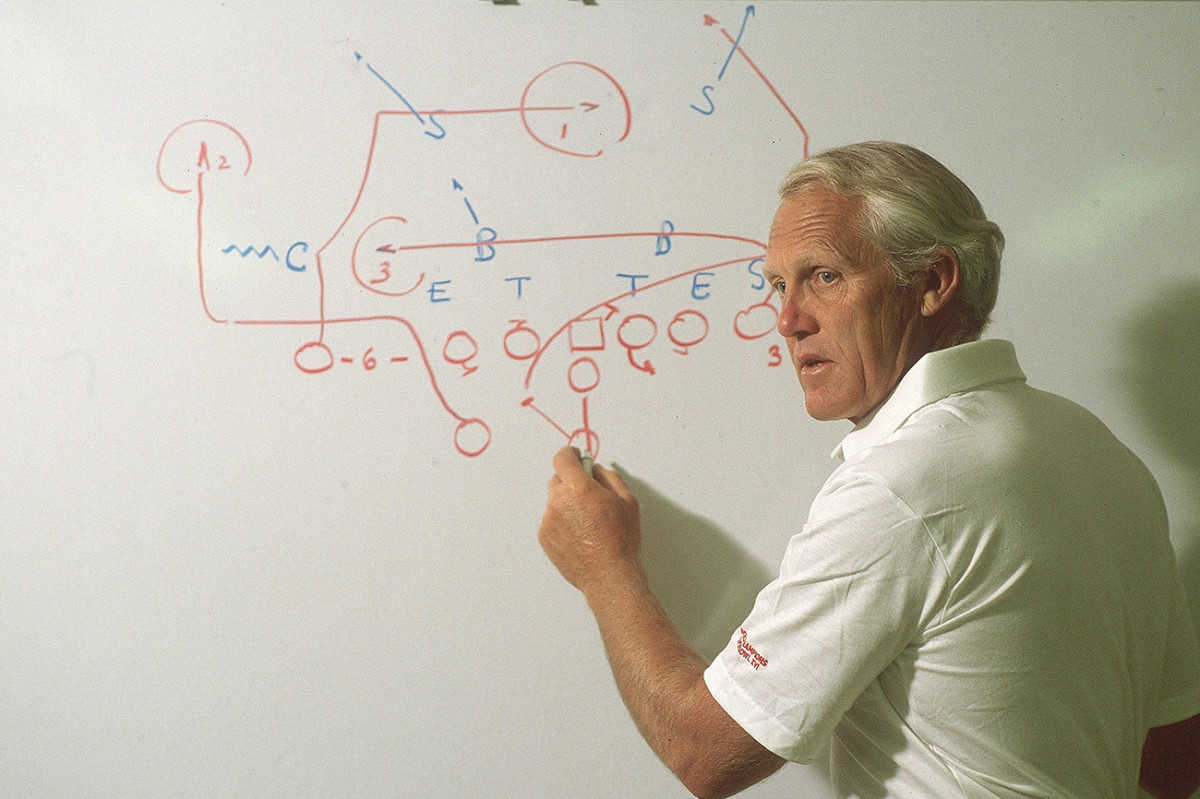

Paraag Marathe arrived in San Francisco with a very clear directive from the 49ers, to reimagine the Jimmy Johnson draft chart. And after a couple months work, the senior associate from the Boston consulting firm Bain readied to show team president Bill Walsh and GM Terry Donahue his findings, in disbelief at the results being spit back at him.

It was uncanny.

“I tried to use historical trends and true value,” says Marathe, now the Niners’ chief strategy officer and EVP of football operations. “And it wasn’t like Coach Walsh was telling me, ‘Hey, a third rounder has more value than it says here, and a second rounder has lower value.’ It was meant to be totally independent. And once I was finished, I looked at all of Coach Walsh’s trades over the years. And it was a total match with all of Coach Walsh’s trades.”

All that work, and all that was proven was what some guy on his couch down the street in Santa Clara could’ve told them: Walsh was a savant.

That was 2001. Moneyball—the best-selling book based on the baseball team across the Bay from the Niners, which would shed light on the coming numbers craze—was still two years from release. The idea of using advanced statistics to drive decision-making in baseball was still in a nascent stage, at least publicly. And that, of course, implies the truth about the NFL then, which is that few in football had even given that concept a thought.

It’s a different time now. Analytics in the NFL have moved well beyond the point where a team hiring a consulting firm to run numbers constitutes outside-the-box thinking. Yet, there remains resistance, a battleground of thought, and a general cloudiness on how far you can take numbers, and how far numbers can take you.

And just the same as 16 years ago, you can place a genius in the center of it.

Perception holds that the Patriots are among the league’s most progressive teams, but there’s precious little evidence of their investment. They have people who are responsible for advanced statistics, but coaches and scouts are largely charged with integrating data gathered into their work. The “analytics guy” there is 64-year-old Ernie Adams, a former Wall Street trader and prep school buddy of Bill Belichick’s.

So why are people so convinced that the five-time champions are knee-deep in the numbers? As one informed long-time NFL exec explains it, “It’s because they’re completely consistent with what sophisticated analytics would tell you to do.”

“[Belichick] does it with intuition,” says one AFC executive. “You know because you’ve been coaching for so long, how you match these 11 guys against those 11 guys. It all makes sense to you. At some point, maybe we can all come to those conclusions without having Bill Belichick’s brain. We’re still a long way from that.”

The NFL is getting closer. The MMQB spent a month discussing analytics with more than 40 team officials from across the league—coaches, executives, scouts and analytics people—and there are some hard conclusions that can be made on where the league is.

1. Most teams don’t shy away from analytics. In fact, more than one official was offended by the notion that their team would be called “old school”. When it comes to player acquisition (which is what Moneyball was based on), the average NFL team is using the data. It’s just that it is being used to generate boundaries rather than drive decisions. Teams want to know when they’re making exceptions on one player, and they want to know what they might be missing on another they may have otherwise dismissed.

2. On the coaching side, analytics are generally used to make staffs more efficient. There may only be time for quality-control coaches to break down four or five of an opponent’s games in the week they have leading into a particular game. And that, in the past, would lead to guesswork on tendencies and strengths and weaknesses. The data allows the quality-control guys, and staffs, to crosscheck against larger sample sizes.

3. The limits in those two areas are the number of games (16) and the variance in players’ assignments and situations that affect plays. That makes it more difficult to collect the amount of data necessary to make hard decisions.

4. Conversely, the value of the data in those areas is proven in that nearly the entire NFL has subscribed to Stats LLC and/or Pro Football Focus, and some rely on smaller services, like Pro Scout Inc., which is run by 64-year-old former Utah coach Mike Giddings.

5. There aren’t sure marks of analytics-friendly operations on game days (as there is in basketball, with teams that go for the “two-for-one” possession at the end of the quarter or half). But on the personnel side, you can see it in asset management, with teams that trade down in the draft to pad their margin for error, and use cap space creatively.

6. There is one strong consensus league-wide: Analytics data related to injury prevention, which straddles sports science and comes through player tracking, is useful and will only get better. The NFL is just scratching the surface with this technology, and the floodgates will truly open only when the league makes available all the Zebra data it’s been collecting. Another step here that’s expected to come eventually is in profiling the minds of players.

7. The Walsh/Belichick robot is not on the market. Yet.

* * *

The cliché is still going strong. On one side you have the gym teacher with the whistle around his neck, on the other it’s the dweeb with the taped glasses, pocket protector, and stacks of hard-to-decipher numbers and data. And, if you believe the cliché, it continues that football’s tough-guy culture has made it slower to change than other sports.

The truth is more complicated. Part of the problem with finding analytics’ place in football is the term itself. Often, the perceived hesitancy to embrace quantitative analysis in the NFL is due to the fact that what is often referred to as “analytics” was already a huge part of the game. It just didn’t have that name.

The game itself is rooted in tactics and strategy and details, and so the study of those has always been inherent in the coaching of the sport and building of its teams.

“I think most of the stuff we’ve done for a long time,” says one NFC general manager. “[Analytics] is the buzzword. That’s how everyone clumps it together now. Like, until five years ago, I’d never heard combine data called ‘analytics.’ But now, someone smart can make it look pretty—analytics. To me, analytics is the Pro Football Focus numbers, finding a way to put a numeric grade on every play and quantify it.

“No one has enough people on staff to do all of that. A lot of it is just statistics, and then what the smart computer guys can make it tell you.”

There’s a lot of gray to cut through. Quality control coaches have forever done what are now considered game-week analytics—identifying opponents’ tendencies, finding trends, and setting up their bosses to game plan. On the personnel side, scouting assistants have, likewise, undertaken analytical studies for decades to uncover advantages and inefficiencies in the draft and free agency.

“Up until 15 years ago, football was probably the furthest along of any of the sports as far as studying the game itself,” says an analytics manager for one AFC team. “It just wasn’t guys from fancy schools doing regression. But there was real systematic study of the game. And frankly, basketball and baseball only started doing the kind of film study that football has done forever just recently.”

So here’s where you start: The reason there isn’t an NFL team ignoring analytics is because analytics has been done in football since Paul Brown came along.

Some teams have very little in the way of analytics staffing and, based on their business practices, are considered advanced. Others have entire departments in place and those who study analytics wonder, based on the way those teams operate, if all their number-crunching has influenced even a single decision.

How is that possible? Well, as Jaguars SVP of football technology and analytics Tony Khan—the son of owner Shahid Khan—explains it: “The adoption rate is far behind other sports.” More than three-quarters of NFL teams employ either a director of analytics or have a full-blown analytics department. Others have their cap managers oversee it.

The divide in the NFL comes in how the data collected is put to work.

“There are a lot of skeptics,” Khan says. “And that’s honestly probably on the analysts and the statisticians. You have to be able to explain it to the football people in their terms. That’s why I try to study that, to be able to communicate with coaches and scouts on a meaningful level, instead of forcing them to use our terminology.”

It’s easy to figure out where and why the divide happens. Football lacks the repetitive one-on-one situations that make up a large portion of baseball and basketball, and it’s tougher to figure out what each player’s assignment is without hearing it from a coach. Those assignments are more divergent, too—in basketball, a center’s role on defense can be affected by the opposing point guard’s movements and decisions and the spacing of all the opposing players; in football, a right tackle’s objective doesn’t relate much to what a free safety is deployed to do.

That makes putting values and creating apples-to-apples judgments on players difficult, and the idea of filtering gameday decisions through a strict set of rules problematic. It also makes it challenging for services like PFF and Stats LLC to find the right way to assess players and plays on their own, and generate value for coaches and scouts.

Then, there’s the issue of sample size.

“In baseball, you have 162 games, and the same exact play starts every play, and that’s the beauty of it,” says one AFC general manager. “You start to appreciate the sheer volume of the numbers, and how they compare over time. In basketball, there’s a natural progression—up and down, up and down. The event of the team going up the court happens so many times, you can chart shots, rebounds.

“And so much of it in both sports is pass/fail. You break that down with the amount of times the events repeat themselves, you can build big data.”

In football, on the other hand, you get anecdotes like this one: There is one team that has a club exec who heads up data collection. He’ll call his head coach into his office and hand the data to him. But the report never makes it to the coach’s desk, only out to the hallway where, between the two offices, there is a trashcan.

* * *

Some teams have analytics directors. Others have departments. Some integrate data and make football people responsible for working it into their jobs. Others keep the sides separate, with an over-the-top manager (usually the GM) sorting it out. Some build their own systems. Others have the numbers people there only as window dressing.

One commonality? Most subscribe to services. Cincinnati-based Pro Football Focus now lists 27 teams as clients, and founder Neil Hornsby says, “I’d be surprised if we haven’t got 32 of 32 by next season, if not this season.” Similarly, Stats LLC has 26 teams as subscribers. The reason? It’s a way to become more efficient and guard against missing anything, even if you’re still not sure how to use all the numbers.

“I come from a consumer product and enterprise software background,” says John Pollard, a former exec at Stats LLC who now works as a consultant. “And what struck me in the early 2000s is when more information and research and analytics became available in over-the-counter pharmaceuticals and retail, it was just too much information. And we’re going through the same thing in sports now.

“It’s being driven by the information. Technology provides the efficiency. And analytics provide more effectiveness in the decision-making. The goal isn’t to replace people. It’s to make them more effective and efficient.”

On the personnel side, there are clear examples of where the numbers are leading to change. In 2009, Dolphins linebacker Joey Porter had nine sacks, but those sacks accounted for an unusually high percentage of his hurries. The Cardinals signed him, at 33, to a three-year, $24.5 million deal anyway. He regressed (6 sacks total over the next two seasons), as the numbers indicated he would, and Porter was out of football before the third year of the contract.

Last year, Bills linebacker Lorenzo Alexander, at 33, had 12.5 sacks. But similar to Porter, those numbers accounted for a high percentage of his pressures, adding to concerns that a clear outlier season in his career would remain one. He hit free agency, and returned to Buffalo on a two-year deal worth less than $6 million.

That’s not to say the aging Alexander would’ve broken the bank in a similar spot 10 years ago. But it did give teams a clear red flag without having to look at 16 games of tape while assessing hundreds of players in building a free-agent board.

And on the coaching side, it backstops a quality control guy’s work. Most QCs only get through four or five of an opponent’s games in a week’s work of prepping a report. Having the extra data on tendencies, situational play, and use of formations and personnel doesn’t mean that assistant can watch more games. It does mean he can crosscheck his findings from the ones he did see.

“The problem with football, they still base a lot of analysis on the previous four games,” Hornsby says. “So let’s say you’re playing Cincinnati, and you want to look at their tendencies when they’re in base personnel. You might wind up with 40 snaps out of 280. And then you’ll make a judgment. Well, of those 40, how many were on third down? How many came on second down?

“So what do you do if there are say, two or three snaps on second down out of base personnel? You have no option but to guess. What you can do with analytics, you’re growing the base data in areas that really matter.”

In many ways, it’s analogous to what technology like XOS has done for film study—where you can call up plays by down and distance, area of the field, personnel grouping, formation, even hashmark. Coaches can now crosscheck their study of four or five games through the data from full seasons, the same way they check out plays by situation without going through a zillion old beta tapes.

* * *

Bill Parcells often told his assistants and scouts, “If you start making exceptions, you’ll wind up with a team full of them.” And therein is where analytics have most affected the most impactful area of player acquisition, the draft. The idea, with the boundaries that analytics set, isn’t to prevent teams from making those exceptions. It’s to ensure they know when they are making exceptions.

A decade ago, there was a contender that had a versatile, smallish back it wanted to complement with a bigger back. The scouts identified one with big college production—over 3,000 yards in a major conference. But the club had five physical parameters for the position, and the back was 0-for-5 on them. The team took him in the third round anyway. That back lasted less than two NFL seasons.

On the flip side, another contender found an offensive lineman deep in the draft, because the team’s “model” liked the conference he’d come from, that he’d started at multiple positions and because, though he wasn’t considered a great athlete, he had a good 10-yard split and vertical leap. That player wound becoming a multi-year starter and, recently, very, very rich.

In both cases, the tape played a role. In the first, it overruled the objective data. In the second, boundaries created a model, and that model sent them back to the tape to find an overlooked prospect that became an incredible value on Day 3 of the draft.

“Maybe your model doesn’t like a guy that your scouts like, so let’s find out why the model doesn’t like the player,” says an AFC personnel executive with a scouting background. “It may be something as simple as the 10-yard split or arm length or a combination of bench press and vertical. It could be position specific. It could be a stat. There’s lots of reasons why a scout may like a player and your model wouldn’t.

“The key is, why are there differences? In a perfect world, the scout and model both like the player, and you get justification. And that happens plenty, but it’s not always like that.”

It’s not an exact science. Advanced analytics, for example, would tell you that an elite pass-rusher needs a 10-yard split on his 40 time in the 1.6s or better. And in 2005, that helped the Eagles, long a leader in football analytics, conclude that University of Cincinnati defensive end Trent Cole (1.67) could carry his college production (19 sacks) into the NFL. A decade later, Cole left Philadelphia behind only Reggie White on the team’s all-time sack list.

This April, those same Eagles took University of Tennessee edge rusher Derek Barnett with the 14th pick, because they believed some of his pedestrian testing numbers weren’t as relevant as his 10 time and short shuttle.

Conversely, in 2014, with ex-Eagles exec Joe Banner in charge, the Browns saw Barkevious Mingo’s off-the-charts 10 time (1.57) and figured he could become an undersized pass-rushing dynamo along the lines of Dwight Freeney. They overlooked the issues with his playing strength and took him sixth overall. Three years later, they were trading him for what amounted to a JUGS machine.

“There are very, very few examples of an NFL player who produced a lot of sacks that wasn’t able to run a 10 time around 1.6,” says Banner, who established an analytics department in Philly in 1995. “Does that tell you who to pick? No. And if you use that solely, you won’t have much success. But if I pick a guy, and I want sacks from him, and I don’t put weight into that, then that’s just not smart.

“Analytics is 95% common sense. Then you have to add sophisticated people who can use it in complex ways.”

The idea of removing some degree of human error is good. To illustrate that point, one team analytics official pointed to a 2011 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that found judges were more lenient after lunch than before lunch. So in football terms, would a GM know if his Southeast area scout got a speeding ticket on his way to LSU before writing a report on their stud corner?

Along those lines, ex-Browns GM Phil Savage used to send his scouts out for school visits after they were in-house for training camp with the warning: Now, remember, you were just watching NFL players. He’d noticed grades on college kids tended to be harsh early, because watching pro athletes would cause scouts to subconsciously raise the bar.

“This information can make you more efficient, it can make you look at more players, and identify outliers, it’s a directional resource,” says Pollard. “But on top of that, it smooths out the emotions. We’re all human. We all develop biases.”

* * *

Few disagree that advanced statistics have their place in checks and balances. They can break ties. They can raise red flags. They can spot another rock to look under. But could the numbers eventually drive decision-making?

The overwhelming consensus, even from many of those who buy into numbers, is that the advanced statistics should be a supplement to the evaluation, not a replacement for it. But that doesn’t mean teams aren’t tinkering.

Many think Jacksonville is all-in on analytics. There was the time they ate salary in the Eugene Monroe trade of October 2013 (a sort of precursor to the Brock Osweilier trade) to get an extra pick from Baltimore. But there have been other moves—such as picking Florida’s Dante Fowler third overall in 2015, despite the fact that Fowler had a prohibitive three-cone time for a top pass rusher—that have confounded those who believe in the numbers.

The truth? Jacksonville, like a few other franchises, has morphed into a mosaic of new age and traditional. And they’ve used college free agency to experiment. Each year, Khan and his analytics staff get to sign a handful of players on their own volition.

In 2015, Khan zeroed in on Auburn’s Corey Grant, liking his 40 time (4.27), his speed score (a measure of a player’s body mass vs. their 40 time), and key metrics (one that showed he had a higher percentage of his carries go for 5-plus yards than any running back in his class). The Jags gave him a $5,000 signing bonus. He quickly became a core special teamer, and rushed for 122 yards in last year’s season finale.

As Khan points out, that is just one small success story, and there’s still a long way to go in learning how effective the numbers can be. But he adds, “There’s a huge level of information we’ve truly never had. … I think it’s like baseball—we’ll look back and see metrics and findings that could’ve been implemented into decision-making earlier. I think there’s useful information right now that doesn’t get used.”

In case you wondered, Khan’s UDFA signings this year: Utah DE Hunter Dimick, Illinois DE Carroll Phillips and Middle Tennessee RB I’Tavius Mathers. And it’s not just guys like Khan doing it. Bucs GM Jason Licht, long a traditionalist, empowers analytics director, Tyler Oberly (plucked from the Sloan conference at MIT), to compile a “Ghost List” of prospects that have fallen through the cracks each spring.

Licht gets the list, which generally has 10-20 names on it, about a month before the draft and hands it off to the scouts working the players’ respective areas, instructing them to give the prospects a second look. The hope is the Bucs can find two or three players each year they might have earlier dismissed, often small-school guys, after the evaluators go back to the tape (showing the emphasis is still on traditional scouting).

Is it working? Well, 2014 undrafted free agent Cameron Brate is a Ghost List alum. The (yes) Harvard product had 57 catches for 660 yards and eight touchdowns last year.

* * *

While the success and failure of those analytics-driven decisions play out, the next frontier of data—player tracking—moves forward. And the NFL actually has former Eagles and Niners coach Chip Kelly to thank for pushing it that way.

Kelly’s Oregon teams implemented Catapult technology years ago to monitor player practice workloads. As Kelly’s teams used it, individual profiles were built on players to provide coaches a roadmap for how hard guys were working, how far they could be pushed, and when they were at risk to suffer soft-tissue injuries. From there grew some of Kelly’s outside-the-box ideas, like having more than just a walkthrough on the day before a game, that still live in the NFL today.

The league, meanwhile, is controlling all the in-game tracking data, via its deal with Zebra Technologies (a competitor of Catapult). So far, its use has been through the NFL’s media arms (with statistics such as “fastest touchdown” and “longest distance run” being presented to fans), and in distributing to teams their own in-game data, which can help in the same way the practice data does.

The next step would be distributing the data from all 32 teams to each individual team, and opening a Pandora’s box that could affect game-planning, free-agent movement and spending, and even scheme elements. The competition committee is studying the idea, but to this point hasn’t even brought it to the teams for a vote.

What could be ahead can be seen in basketball. Similar to Tony Khan’s acquisition of TruMedia, Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban was out in front in purchasing Synergy Sports, which built the precursor for player tracking. Today, SportVu, through Stats LLC, provides teams and the public with detail like this: In Game 2 of the NBA Finals, Cleveland was 10-for 34 and Golden State was 10-for-35 on uncontested jumpers.

In baseball, tracking has revealed the answers to second-order questions. Analytics, for example, long held it wasn’t smart to invest in stolen bases, but technology shows how having a dangerous runner on the base paths can affect a pitcher’s performance and provide help for teammates at the plate.

In football, with the context of data from both teams on the field, rather than just one of the two, the technology could track separation a receiver gets from a corner, or how swiftly a defensive end disengages from a tackle in rushing the quarterback, or the velocity with which a ball arrives from the quarterback on difficult throws.

The problem is that finding a way to sort through the data and figure out what it means will take time, trial and error. But at least a few teams have integrated sports science with the on-field analytics. One of the best players in football is a living, breathing testament to that.

The Falcons used analytics to determine the price they were willing to pay to move up 21 spots to get Julio Jones in the 2011 draft. Their analysis showed that fourth-round picks were of limited value to them (so they included two in the deal), and number crunching allowed them to assess his fractured foot and create comps for him. Since that draft day, they have used analytics to create an athletic model to measure other players against, ID ideal matchups for Jones in games, manage his injuries and build his five-year, $71.3 million deal. Six years in, Jones is Exhibit A of Atlanta’s investment in the numbers paying dividends.

* * *

If there’s one team that’s believed to be allowing analytics to drive decision-making, it’s the Browns. The team’s top shot-caller, EVP of football operations Sashi Brown, has made deep investments in that area, with the hiring of chief strategy officer Paul DePodesta (once the top assistant to the inspiration for Moneyball, Billy Beane, in Oakland) and a staff of number crunchers.

Cowboys analyst Ken Kovash was poached in 2013, and promoted last year to vice president of player personnel, an identical title to the one held by the team’s top scout, Andrew Berry. Three others in player personnel have “research,” “strategy” or both in their titles. And in consistently dealing down and for future assets, and making trades like the Osweiler deal, most believe the Browns are all-in.

Yet, Brown (at least publicly) isn’t entirely comfortable conceding that.

“Our structure isn’t designed to give rise to analytics, but to the end we want to incorporate it, I think it’s a desire to win,” Browns says. “If you tell me there are some answers out there or some information out there that can improve our team, stuff that we don’t have, I don’t care what you call it, I’m interested. Now, it’s gonna have to prove its mettle. And that’s the process that we’re in, trying to discover whether there’s some real answers out there.

“But if you are honest and open about your objectives, humble enough and non-territorial enough, then I think it’s a natural thing that most people would want. If you’re gonna be an organization that says, ‘It’s been done this way for however many years, and we’ve got to keep doing it that way, and nobody else from any other discipline can influence a decision,’ then good luck. It’s a new century.”

The Browns were 1-15 in 2016. So it’s tough to sell them as forerunners at this point. Conversely, everyone has been trying for years to figure how the Patriots do business. And yes, New England’s actions match cornerstones of football analytics.

The Patriots flip fourth- and fifth-round picks, routinely, for veterans—dealing off guys that typically have around a 15% success rate for proven commodities. It’s how New England got Randy Moss in 2007. It’s how they landed Dwayne Allen this year. It’s also where they struck out on Albert Haynesworth and Chad Johnson one summer, and still made the Super Bowl that winter.

The team is built sturdy up the gut, and with pass-game weapons—big tight ends and shifty slots and backs that can catch—equipped to exploit coverage-deficient players in the middle, the theory being that it doesn’t make sense to over-invest in challenging the defenders who are best (corners) at covering your skill position players.

And the Pats deal down in the draft, manage the cap with balance across the roster, and strike on inefficiencies. (Having Tom Brady doesn’t hurt either, of course.)

But does all this mean Belichick is in on analytics? Or, as more believe, is he logical to the point where any objective study matches up with how he has built his team?

Marathe would tell you the latter is probably a little closer to the truth, much like he learned about Walsh when working on the new draft chart 16 years ago.

“It’s just establishing and understanding value,” Marathe says now. “The adjective I’d use is ‘unemotional.’ It’s unemotionally understanding the value. And maybe the value doesn’t match up in certain cases. [Walsh and Belichick] are both, with what I’ve observed with Belichick, very good at keeping that emotional distance. They stick to what they believe in. Fifteen years ago, the Patriots cut Lawyer Milloy. That’s a Pro Bowl safety, a captain, and they decided he just wasn’t worth the money they paid him. That’s the sort of stuff that Coach Walsh did.”

Is it that analytics? Sure, it is. And at the same time, it’s just football, the way it’s always been.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.