Every NFL Play Is a Brutal Game of Chess

We hear all the time that football is a chess match. But in football, the pieces move all at once, and the movements aren’t constricted to certain squares and patterns. Plus, everyone’s pieces are different. And every piece runs the risk of getting knocked down and taken out of the play. There’s a lot going on with every snap.

To better understand this, we called upon one of the most respected assistant coaches in the NFL: James Urban, the Bengals’ seventh-year wide receivers coach. Under Urban, A.J. Green has fulfilled his superstar potential. Mohamed Sanu improved to the point where we earned a big free-agent contract from Atlanta last offseason. Marvin Jones also got one from Detroit. Last season Brandon LaFell joined the Bengals in free agency and outperformed Sanu and Jones’s numbers from the year before, catching 64 balls for 862 yards. Now Urban is working with young receivers Tyler Boyd (a second-round pick in 2016) and John Ross (the ninth overall pick in 2017). Prior to coaching Cincy’s wide receivers, Urban was Andy Reid’s quarterbacks coach in 2009 and ’10. You might recall 2010 being the season that Michael Vick recaptured his magic and had the best season of his career.

Urban spent over an hour taking us through two plays from Cincinnati’s Week 7 game against Cleveland last year. It was quite the lesson. We’ve lightly edited his analysis for length and clarity, but we’re going to let the expert take it from here.

* * *

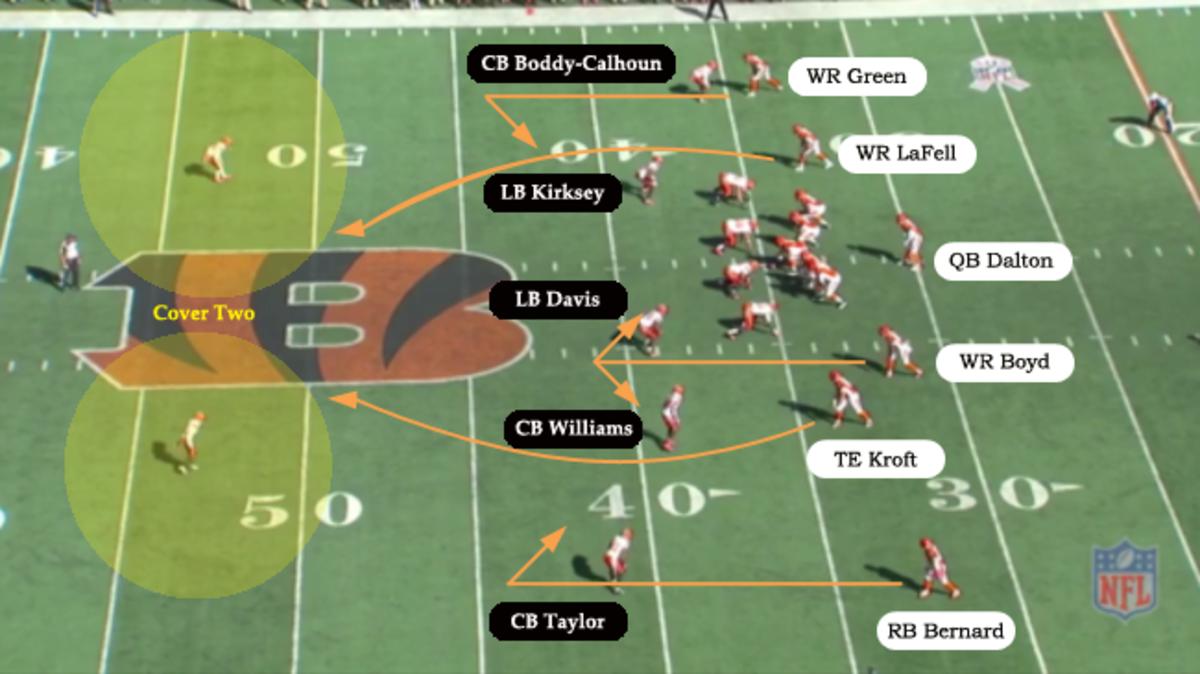

This is a 21-yard completion to Brandon LaFell. We’re in an empty formation. By putting all five eligible receivers outside the offensive tackle box, you create a clearer picture of which defenders the offensive linemen must block. On this play, there are two high safeties and no linebackers inside the box. Our five O-linemen just have to handle the four defensive linemen.

In most empty formations, you’re in a 3x2 set, with three eligible receivers to the wide side of the field and two eligible receivers to the short side of the field (the boundary). That’s what you see here. On this play, we put our two starting wide receivers, A.J. Green and Brandon LaFell, to the boundary. To the wide side of the field we have, beginning from the outside in, running back Giovani Bernard, tight end Tyler Kroft and wide receiver Tyler Boyd.

We see cornerback Jamar Taylor lined up across from Bernard. On the inside, linebacker Demario Davis is across from Boyd. This reveals that it’s zone coverage. If it were man, the cornerback would have followed our wide receiver, Boyd, inside and the linebacker would have gone with our running back, Bernard, outside.

So our quarterback, Andy Dalton, knows that it’s zone coverage. He can also see that it is a two-high safety coverage. There are a few basic variations of two-high safety zone coverage:

• Cover 2, where each safety rolls over the top of the outside corners and is responsible for a deep half of the field.

• Cover 4, where each safety is responsible for his 1/4 strip of the field (the outside corners each have the other 1/4 strips).

• Cover 6, which is Cover 2 on one side and Cover 4 on the other.

This is a pretty clear Cover 2 look. Both safeties are aligned inside the field numbers and are many yards deeper than the cornerbacks. If it were Cover 4, the safeties would be aligned a few yards closer to the line of scrimmage.

The design is a concept built off our “4 verticals” play. On “4 verticals,” you have four deep routes (usually run by the two widest-aligned receivers on each side) plus an underneath option route (usually run by the running back; on this play, it is run by the tight slot receiver, Boyd). On an option, the receiver has the option to take his route inside or outside, depending on his defender’s location.

This play, however, is a variation of our “4 verticals.” The slot receivers, LaFell and Kroft, will run vertical “bender” routes down the seams. But the widest-aligned receivers, Green and Bernard, will run hitch routes. To a defender, a hitch route initially looks the same as a vertical Go route.

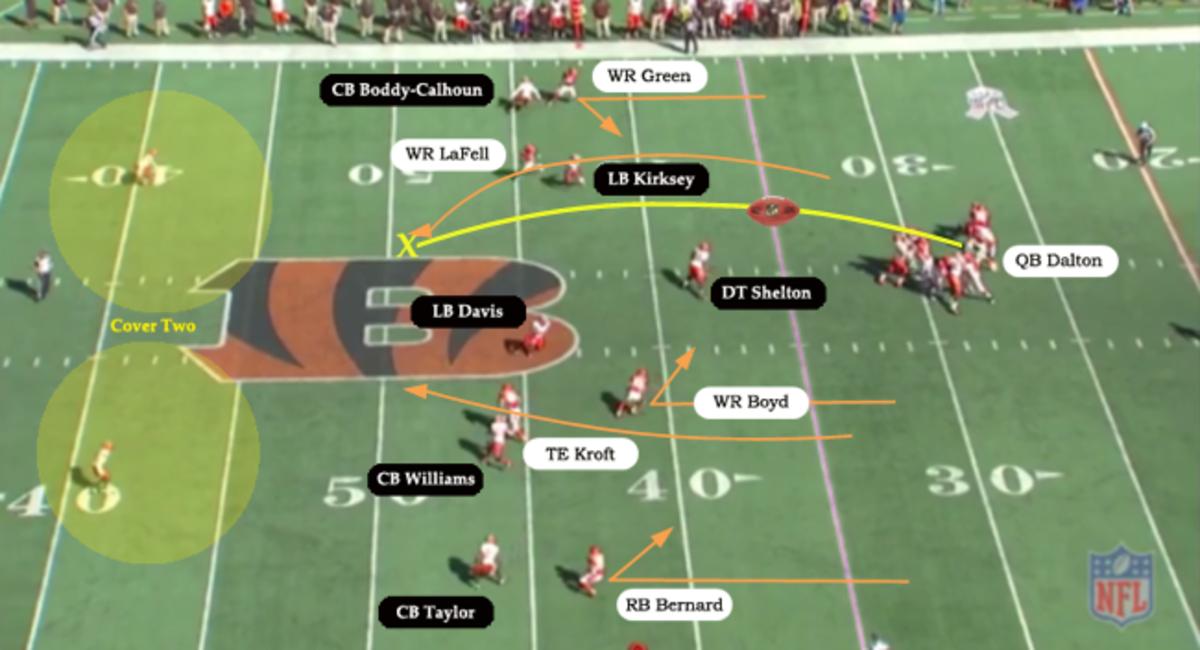

Against Cover 2, Dalton will work LaFell’s or Kroft’s “bender” route along the seams. The idea is to throw over the top of the linebacker and in front of the safety. LaFell is able to do that, even though linebacker Christian Kirksey plays it pretty well. (It’s tough for a linebacker to guard a wide receiver.) The ball needs to be placed 18 to 22 yards downfield. Any shorter and Kirksey can reach it. Any further and that safety over the top can reach the ball or drill LaFell.

There’s a variation to this Cover 2. Defensive tackle Danny Shelton drops underneath, making it a three-man rush and putting eight defenders in coverage. More and more defenses are dropping eight defenders against spread empty formations such as this one. Shelton’s presence impacts Boyd’s option route, which we’ll get to in a minute.

On these seam “bender” routes, each receiver’s primary defender has different leverage. The linebacker near LaFell, Kirksey, is playing inside of LaFell. The slot corner near Kroft, Tramon Williams, is playing outside of Kroft. In the NFL, you’re facing the best coaches and the best players in the world. You assume they’re playing these defensive techniques for a reason. Kirksey is inside of LaFell by design and Boddy-Calhoun is outside of Kroft by design. This impacts how each man runs his route.

When running a route, a receiver must attack the individual coverage technique of his primary defender. We teach our receivers to read their primary defender and their side of the field, not the whole defense. It’s the quarterback’s job to read the whole defense. By limiting the receivers’ reads, you allow them to play fast.

On this play, the Browns had not disguised anything presnap. LaFell knew the whole way that Kirksey would be inside of him. LaFell initially attacked Kirksey’s outside shoulder. Then, LaFell drifted outside, dragging Kirksey with him. This created the space to complete the top of the “bender” route. The second LaFell got over the top of Kirksey, he whipped his head around. This is a timing-based throw; he knew the ball would have to be in the air by then.

Kroft did a similar thing on the other side. He initially stemmed his route outside ever so slightly, which caused his defender, Williams, to widen. That set up the angle for Kroft to bend his route inside. The ball didn’t go to Kroft because middle linebacker Demario Davis was over on his side. That left LaFell with the one-on-one matchup (against a linebacker, no less). Dalton threw a strike to LaFell.

Davis was toward Kroft’s side because that’s where our tight slot receiver Tyler Boyd was. Let’s examine Boyd’s option route. It has a lot of pieces. First off, the defense is in Cover 2, not Tampa 2. The difference is that in Cover 2, the middle linebacker stays in the shallow middle of the field. In Tampa 2, that middle linebacker sinks back deep down the middle. If this had been Tampa 2, those seam “bender” routes would probably not be open. Those are longer throws and that sinking middle linebacker would have time to react. Dalton would have likely targeted Boyd underneath.

• TOM TAYLOR: Football’s Next Frontier—The Battle Over Big Data

At the snap of the ball, Boyd must peak inside. If no defensive linemen drop back, he carries his route inside and runs the option over the shallow middle of the field (it’d look like a crossing route initially). However, in this case, you have DT Danny Shelton dropping back. So instead of running inside toward Shelton, Boyd keeps his route outside and options off of that middle linebacker, Davis.

Here’s the tricky part: Boyd is only optioning off of Davis because it’s Cover 2. If it would have been Tampa 2, Davis would have been aligned two or three yards deeper before the snap and would have been sinking back after the snap. Boyd would then have taken his route inside and run his option off of Shelton. In certain designs, it’s important that Boyd use his option route to attack his primary defender. If he is running it on the linebacker, we’d want him to run at the linebacker. If he is running it off the defensive tackle, theoretically, we’d want him to run at the defensive tackle. We’d do that to help open Kroft’s seam “bender.” If Boyd sucks the middle linebacker in, there’s a clean window to Kroft.

On this play, however, the routes are not intertwined. In this “4 verticals” concept, Kroft’s seam “bender” is unrelated to Boyd’s option route. Which means we want Boyd running his route to get himself open. So here, instead of attacking LB Davis, Boyd runs six yards and simply turns around. Take the easy stuff.

If we ran this concept the next week, we might put in the wrinkle of having Boyd attack the middle linebacker in order to create a clear window for Kroft. It just depends what we see from the defense on film that week.

One small negative on this play: Boyd initially stemmed his route toward the outside, running it behind Kroft. He should not do that. We do call those tandem releases at times, but not on this play. Boyd should just release straight downfield off the line.

If this had been Cover 4, instead of Cover 2, those “bender” seam routes would have been impossible because they go right down the 1/4 strips of the field that the safeties are covering. Dalton in that case would have thrown to one of the hitch routes outside. Dalton also would have worked those hitch routes if it had been a single-high safety coverage. That would have left one-on-one coverage all the way outside.

• ALBERT BREER: Analytics and the NFL—Finding Strength in Numbers

Let’s talk about Dalton’s options on those hitch routes. He’d have a choice to make: throw to Green or throw to Bernard? On the surface, the choice is easy: you throw to your superstar receiver, Green, especially with him on the boundary side, which makes for a shorter throw. But notice the cushion that cornerback Jamar Taylor has on Bernard down below. That can be tempting, too. But remember, Bernard is not accustomed to running routes. He’s a running back. His practice reps are spent primarily on running plays. When he does practice a pass play, he’s often practicing a blitz pickup. So you’d have to really like the cushion Bernard is getting from that corner if you’re going to throw to him.

On this play, Green released his hitch route outside of the cornerback. In certain designs against Cover 2, the outside receivers have a mandatory outside release. In other words, their first few steps on their downfield routes must be toward the sideline. (This is usually to create more space for a quick-out route for the slot receiver inside of them.) That was not the case here. Green released outside, but only because his corner cheated so far inside.

There are also cases where Green’s hitch route could convert to a Go route. We like to convert hitch routes into Go routes against bump-and-run coverage by a corner or against certain Cover 2 looks. It was Cover 2 on this play, yes, but on this particular play design, Green’s route was “locked.” In other words, he had to run a hitch no matter what.

* * *

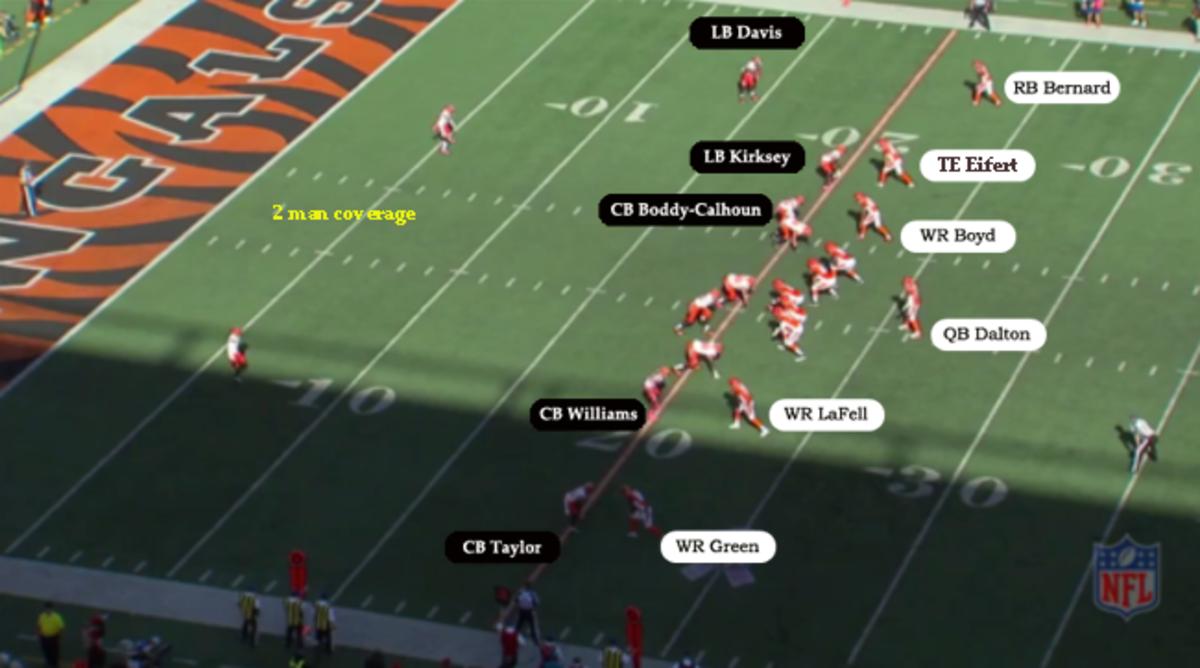

Later in the game, the Bengals ran a similar concept. Only this time it was in the red zone and the Browns played man-to-man.

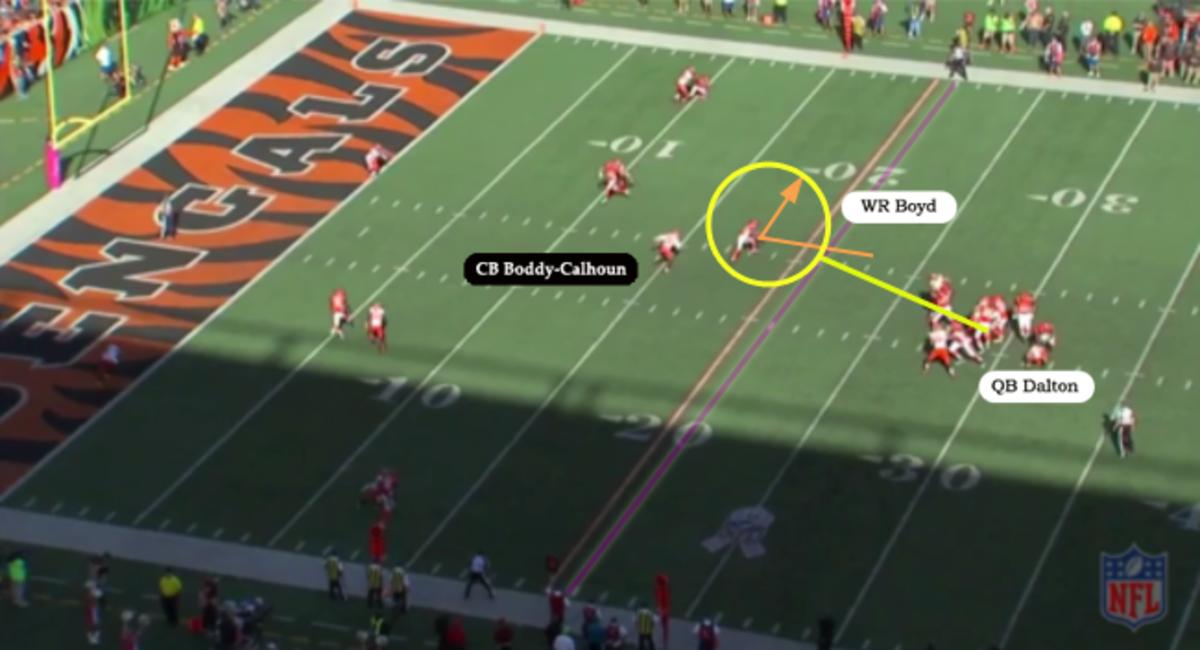

So here is the same formation as before, only flip-flopped. Now we see LB Christian Kirksey follow Bernard outside and cornerback Briean Boddy-Calhoun follow Boyd into the slot. This tells Dalton it is man-to-man. With the two safeties so wide like this, Dalton also knows it will be “2 man.” (That means man-to-man with two safeties over the top.) It is highly unlikely that either safety would become a robber and swoop into the middle of field. This is all expected; it was third-and-5, a situation where you often see “2 man” coverage.

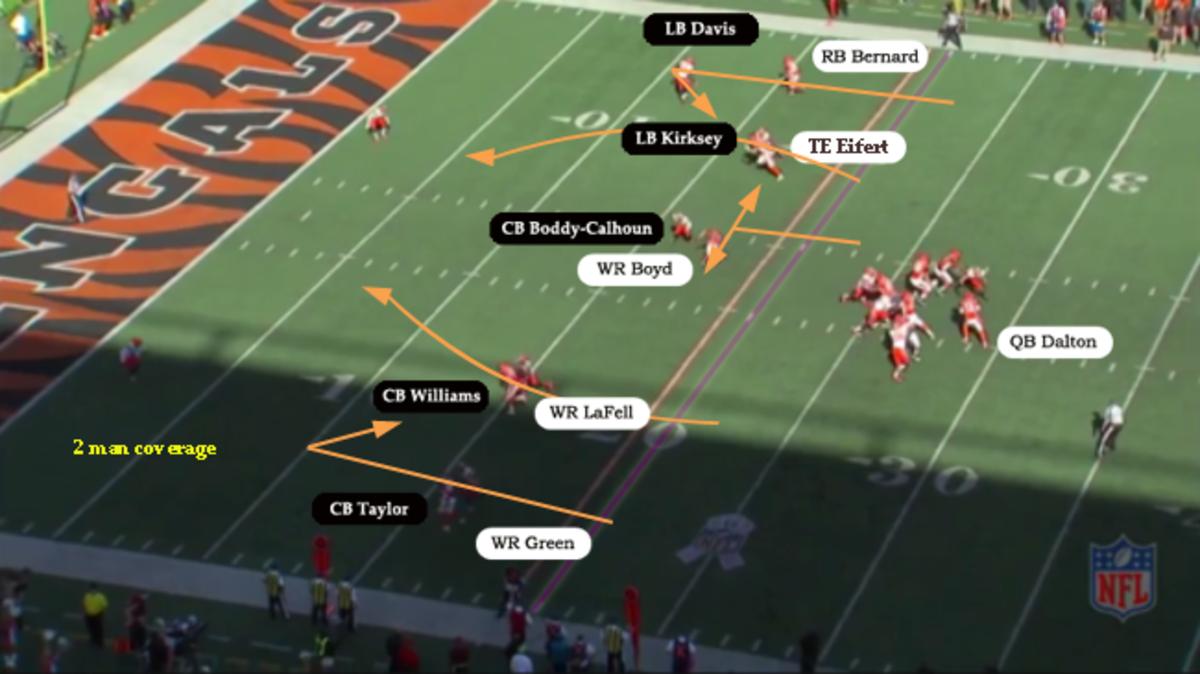

In “2 man” all of the defenders play inside of their receivers. The two safeties over the top make it very difficult to throw vertically, especially on the seam “benders.” However, you get a great opportunity with your option route. Here you see Boyd one-on-one in the middle of the field against Boddy-Calhoun. It’s a four-man rush this time, not a three-man rush, so no defensive lineman is dropping back. There is a ton of space for Boyd.

In the event that Boyd absolutely burns Boddy-Calhoun off the snap, he can convert his option route into a crossing route and just keep running. Nine times out of 10, however, the cornerback will be in position to still chase down the receiver after the catch. So it’s imperative that the receiver gain his separation before the throw, which usually requires that he follow through with the original option route.

To gain separation, Boyd will start out on a crossing route but then sharply cut back the other way.

Boyd did a tremendous job. Look at the separation he gets from Boddy-Calhoun. This is not a timing and anticipation route like on the previous play. It is a “see it” route. Dalton must see Boyd get open before he can throw. Boyd shouldn’t look back to the quarterback until he is ready for the ball. That’s how Dalton knows to throw it. We get everything you want here, but the pass protection does not hold up. The pocket closes down, creating an inaccurate throw. Boyd must go to the ground to catch it. Gain of three, creating fourth down.

* * *

This is the kind of stuff Urban spends his days teaching. Increasingly more, pro football is an academic endeavor. Players spend more time in the classroom than they do on the practice field. Position coaches like Urban, who can teach their players not just the mechanics of their job but how their job fits into the greater sum of the offense, are the ones who become coordinators. They’re the ones who eventually usher along the game’s evolution.

Question? Comment? Story idea? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com