Ten things you (probably) didn't know about Bruce Arians, the Cardinals' head coach

The following is excerpted from the book The Quarterback Whisperer by Bruce Arians, to be published on July 11, 2017 by Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group. Copyright 2017 Bruce Arians.

Did you know Thursday night is date night in Bruce Arians’s household? That the Cardinals coach once earned the nickname Esquire Smooth? That Joe namath told him he’d outkicked his coverage in marrying his wife, Christine (and that she said she’d leave Bruce for Broadway Joe in a heartbeat)? In anticipation of Arians’s new autobiography, we present for you our favorite mini-excerpts from the page-turner. Consider this: 10 Things You (Probably) Didn’t Know About One of the NFL’s Most Successful Coaches.

1. On that nickname. . .

My family moved to York, Pa., when I was eight. As a kid I spent virtually all of my free time at Memorial Park, which was just down the street from my house on Springdale Avenue in our blue-collar neighborhood.

Some of the older guys at the park were African American, and I never thought twice about our different skin colors. One of the older black guys was named Eddie Berry. He played offensive line at York High and he gave me my first nickname: S.Q. Smooth.

Esquire Smooth. I loved it. I carved it into the picnic tables at the park. Getting that nickname meant I was accepted at the park, and it did more for my confidence than anything else I ever did as a kid.

Buy Now

The Quarterback Whisperer

by Bruce Arians

What makes an elite QB? In recent history, one man is the common thread that connects some of the best: Peyton Manning, Ben Roethlisberger, Andrew Luck, and the resurgent Carson Palmer.

2. On bartending life. . .

In what may have been a first in college football history, after home games [at Virginia Tech, where he played quarterback in the mid-’70s] I dished out drinks from behind the bar at a restaurant named Carlisle’s. I probably violated some NCAA rule, but I needed that dollar-an-hour and the free steaks.

Later I left Carlisle’s to tend bar at a basement nightclub in Blacksburg. One evening a man who I knew lived up in a cabin in the Blue Ridge Mountains sauntered in looking for trouble. He looked like he was straight out of the movie Deliverance. His long Rip Van Winkle–like beard may have been home to several different critters.

“Tonight,” the man declared to me, “I’m going to drink and I’m going to fight.”

“Well,” I replied, “let’s make the beer free for you, but go fight somewhere else.”

A few hours passed. Then the man, filled with liquid fire, started pinching the posteriors of several different young women. I told him he had to leave.

The mountain man pulled out a black handgun and stuck it in my belly. “Throw me out now,” he calmly said to me.

I was terrifed. It’s generally not good when an intoxicated man is pointing a gun at you. But just then the nightclub owner, wielding a blackjack, clubbed the man over the head, knocking him out cold.

That was my last night of bartending. I realized, when that gun was jammed in my gut, that perhaps coaching would be a better career path. My beautiful wife agreed.

3. On an old Cowboys trick. . .

After my final season in Blacksburg, I got a call from the Dallas Cowboys. A scout said they were interested in me. Then they sent me a letter and a pen. “We hope to sign you to your contract with this pen,” the note said. I was thrilled. I proudly showed off the pen to Coach [Jimmy] Sharpe, who had become my mentor.

“You do realize,” Sharpe told me, “that the Cowboys have sent about a thousand of those pens to college seniors across the country.”

Ah, I hadn’t, but I tried to play it cool. “Of course,” I said. “I’m not holding my breath or anything.”

Away from the NFL spotlight, financial ruin drove Clinton Portis to the brink of murder

4. On his first encounter with Peyton Manning. . .

I got to know Peyton Manning when he was a high school junior and I was the offensive coordinator at Mississippi State. His father, Archie, had been a legendary quarterback at Ole Miss, and it didn’t take a recruiting genius to understand there was no way Peyton would ever come and play for us at Mississippi State, the sworn rival of the Ole Miss Rebels. But I was in charge of recruiting quarterbacks and so I called Archie one afternoon and asked, “Hey, is there any way Peyton would consider coming to play for us?”

Archie laughed so hard he must have doubled over. No, Archie told me in his southern, sugar-polite way, Peyton would not be attending Mississippi State.

5. On later fixing Peyton’s Patriots problem, with the Colts. . .

Before a December 1999 game against the Patriots, I saw during pregame warm-ups that Peyton was a live wire of nervous energy, crackling with anxiety. He fidgeted like a Mexican jumping bean and he had a frowning, contorted face. Frankly, he looked like he really needed to go to the bathroom, even though he was all clear on that front.

Peyton kept fidgeting with his equipment. This was, in poker parlance, a classic tell, because I knew that whenever he adjusted and readjusted his left kneepad, he was really upset about something. Peyton can obsess with the best of them, and I knew he needed to be calmed down. I approached him on the field, determined to shift his focus.

“Peyton, your footwork is all messed up,” I said. “What’s wrong with you, man?”

Peyton then spent the final 10 minutes of pregame perfecting his footwork, even though I saw that it had been flawless during his warm-up. I wanted him to quit worrying about the fact that we were about to play a team that had been his nemesis, his kryptonite. We’d lost three in a row to the Pats. And sure enough, Peyton’s mind became so locked onto taking precise five- and seven-step drops that his anxiety vanished into the crisp December air.

After I got Peyton to focus on his footwork, it was as if his worries magically melted away. He was one smooth operator, brother. Playing cool, calm and cerebral, he threw two touchdown passes and no interceptions in our 20–15 win over the Patriots, which was Peyton’s first ever victory over those guys.

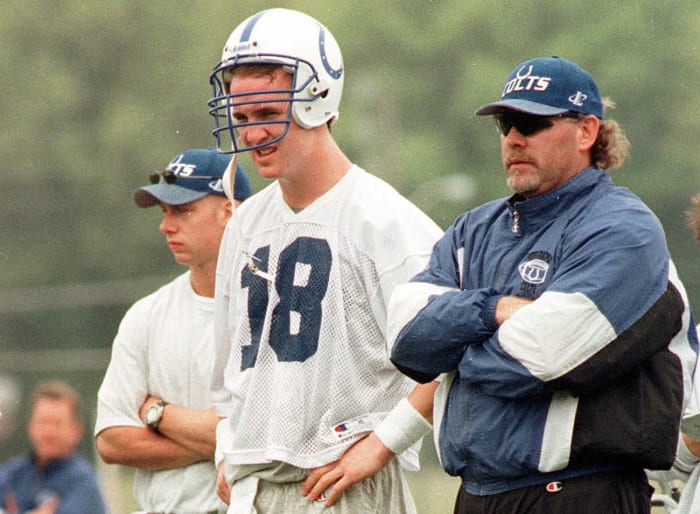

Peyton Manning and Bruce Arians (right) watch Colts practice during the team's minicamp in 1998.

Seth Rossman/AP

6. On the real Peyton. . .

In Indianapolis he was infamous for not being able to properly use a can opener. One time I visited him at his place and saw that he had pictures that his mom had given him on a closet door, showing what shirts went with what pants and shoes; she had picked out his outfits as if he was still in grade school. He kind of struggled with the basics of life, and it was a source of great comedy for his coaches and teammates. But he took all the jokes in stride.

7. . . . and the real Peyton. . .

He was an inveterate practical joker. He really loved messing with his backup quarterbacks. When Steve Walsh was his backup in 1999—Peyton’s second year in the league—Steve brushed his teeth like 10 times a day. So one day Peyton bought a toothbrush that looked just like Steve’s. He then took a dump in the toilet, threw the toothbrush in there and snapped a Polaroid of it. At lunch that afternoon he asked Steve if he had brushed his teeth that day. Steve said he had. Peyton slid the photo over to him, and Steve almost started throwing up.

8. On his trunk tavern in Pittsburgh. . .

I work hard, but I also play hard. Everyone needs balance in life. And so after a win in our yard during that [2008] season, I’d shower, change, do interviews and then head for my car parked in the players’ and coaches’ lot. I’d pop open the trunk and would have a few coolers chock full of drinks on ice: beers, bourbon, vodka. You name it, I had it.

I’m a Crown Royal sipper. Once I got to the car, I’d pour a drink for myself and then start pouring more for the players and coaches who gathered around my ride. These little post-game parties were some of my happiest times in Pittsburgh—I still throw them in our parking lot in Arizona—because for an hour or two we can relax and enjoy each other as friends, not coworkers or teammates, just pals. I loved it. Players and coaches brought their families over. We were just like everyone else who tailgated in parking lots after the games—friends and family enjoying each other’s company.

Vince Young's journey north to rewrite the ending of his football career

9. On his bitter end with the Steelers. . .

After losing to Denver and Tim Tebow in the first round of the playoffs in January 2012, I met with Mike Tomlin, our head coach. Tomlin told me he was going to try to get me a raise in the off-season.

But a few days later, I was in the basement of our Reynolds Plantation home when Mike called. His voice sounded funny. I immediately knew something wasn’t right.

“What’s up?” I asked.

“I couldn’t get you the raise,” Mike said. “I couldn’t get you the contract.”

“That’s alright,” I said.

“No, no,” Mike said. “I couldn’t get you any contract.”

“Are you firing me?” I asked.

“I would never do that,” he said.

“Do I have a contract?” I asked.

“No,” Mike said.

“Well, then you’re firing me,” I said.

Mike asked me to come to Pittsburgh so we could talk. I told him “hell no” and I told him not to fly to Georgia to see me. I was hot, man. I was pissed.

10. On handing the keys to his QBs. . .

To show my quarterbacks how much I believe in them, I let them pick their favorite plays that we’ll run in the game. On the nights before a game we’ll sit down in a hotel conference room and we’ll have six third-down calls for certain distances. On third-and-five, for example, I’ll ask my quarterback to give me his top three plays that he wants to run in that situation. Then on game day we’ll do that. Not only does this give ownership of the game plan to my quarterback, but it also makes him more accountable for what happens during the game. I want my quarterback to feel like we are tethered at the hip—and at the heart.

I’ll also ask my quarterback at our Friday meeting to give me his 15 favorite pass plays. Then I’ll get 15 running plays from the coaches and I’ll script the first 30 plays. If there is a pass play that I really want to include in those first 30, I’ll put it on the projector and make my case to the quarterback. But if he strongly disagrees, then I’ll let him win that argument. Remember: Players make plays, not coaches. So it’s vital that the quarterback be comfortable with the plays we will run. Because if he’s not, no matter how much I’m in love with a certain play design, it won’t work if my quarterback can’t execute it.