Peyton Manning Statue: The Meaning Behind the Monument in Indianapolis

INDIANAPOLIS — When I started in the sportswriting business, in 1980, one of my jobs at the Cincinnati Enquirerwas as backup beat writer covering the Reds. In those days, their Triple-A team was in Indianapolis, and a couple of times a year I’d drive two hours up I-74 to write about some future Red. Indianapolis was sort of old and dusty and definitely minor-league, with a rickety ballpark and a downtown with nothing happening, at least compared to Cincinnati. Maybe not quite how native Hoosier David Letterman described Indy of the 1960s on Saturday (“like a minimum-security prison with a racetrack”), but still far behind mid-sized cities like Cincinnati. More Letterman: “People would say, ‘Dave, we’re planning a trip to Indianapolis, what should we do?’ This was years and years ago. I said, ‘This is what I’d do if I was going to Indianapolis. I’d rent a car and go to Chicago.’”

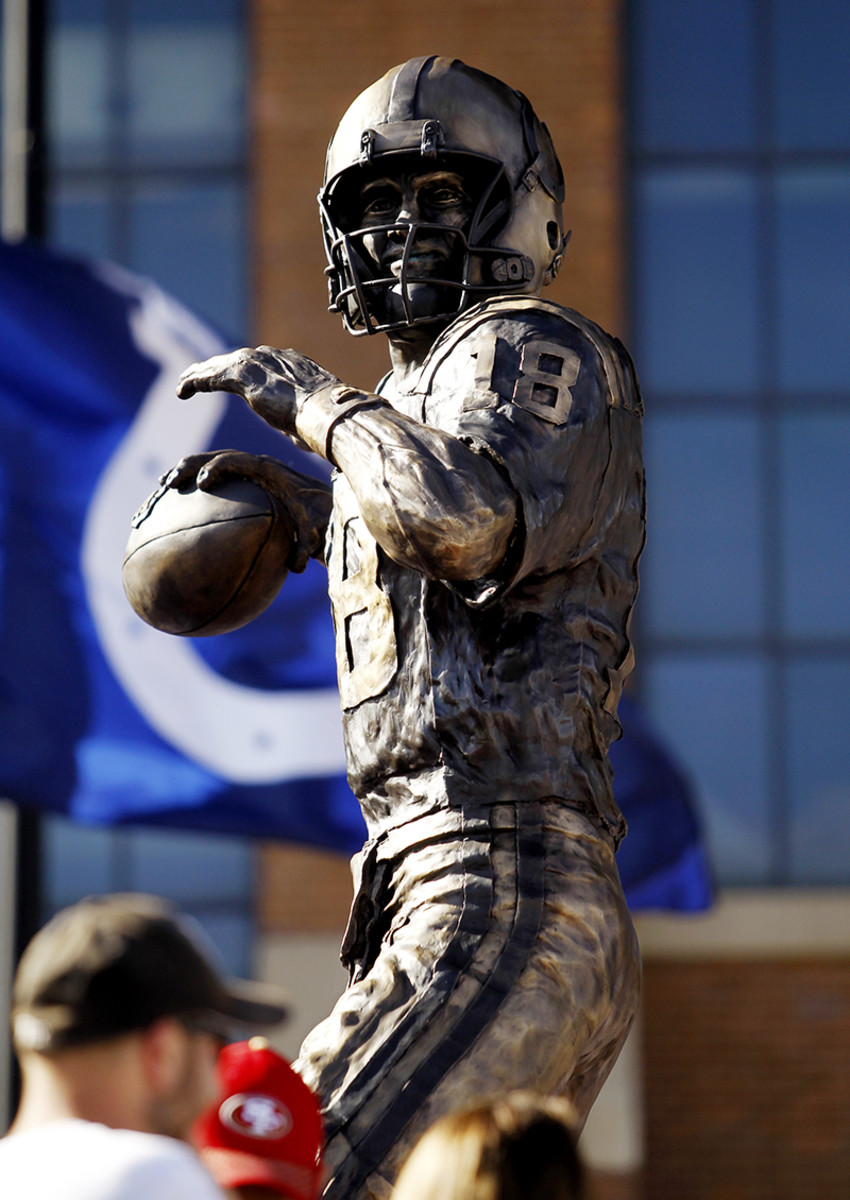

So now Indianapolis, with its compact downtown jammed with hotels and restaurants, has hosted a Super Bowl—and the city performed so well the NFL might go back for a second one day. Indianapolis has won a Super Bowl. Indianapolis hosted had Final Fours, men’s and women’s. Indianapolis is even hip, with Manhattan-caliber restaurants like Bluebeard. On Saturday, with two big conventions and a Colts game on the slate, downtown was bursting at the seams; there was a line at St. Elmo’s. And a crowd of 10,000 to 12,000 people came to the city to watch the unveiling of the half-ton bronze statue for the man who, more than anyone, made it possible. GM Bill Polian always maintained that Lucas Oil Stadium got built on the back of Peyton Manning, and the former two-term governor, Mitch Daniels, echoed that in remarks to the adoring crowd. Locals were giving Daniels a hard time about the cost of Lucas Oil Stadium early this century, and he said: “Just build it. Peyton will fill it.” Fitting, too, that the shiny upscale JW Marriott—representing boom times in the first 17 years of this century for $320-a-night rooms in ritzy downtown hotels—could be seen through the legs of the bronze number 18.

“He didn’t do it alone,” Letterman said. “But by God, look around us. He changed the skyline. This used to be a small town. This man has changed the skyline.”

Never wonder again about the effect of a winning quarterback on a city, a state, a region. It’s why every team that doesn’t have Aaron Rodgers or Matt Ryan spends so much time and money looking for one. As Browns owner Jimmy Haslam told me this summer: “There’s nothing that compares to it. You need a great starting pitcher, a great closer in baseball. You need a great point guard in basketball. But there’s not one position that comes anywhere close in sports, I don’t think, to quarterback in football. If you ask any one of our football people, they’d all say getting the quarterback right is number one. I can tell you this: It’s on the top of our list daily. Once you get that, the game’s much easier.”

Peyton Manning Talks Football, the Future and Life in Retirement as a Carpool Dad

Four other thoughts on the Manning event:

• There is no safe haven for Roger Goodell. The NFL can, and certainly will, slough off the reception for the commissioner here, but I found it notable, to say the least. The setup of the program paired speakers together, something I’ve never seen at a public event. The MC made a short introductory talk about each man and asked both to come up at the same time. One spoke, one sat between Manning and Colts owner Jim Irsay. Jeff Saturday, Manning’s longtime center, introduced (oddly) with David Letterman. Bill Polian introduced with the former governor of Indiana, Mitch Daniels. Goodell introduced with former Colts coach Tony Dungy. Now why were the speakers introduced this way? And why was Goodell introduced with Dungy, the most revered person in the crowd outside of Manning? Take a guess. When Goodell took the podium to speak, he was greeted by boos from—this is a very rough estimate—about half the crowd of maybe 10,000 to 12,000 fans. It seemed stunning, on such a celebratory day, with such good and warm feelings, that such a folksy town like Indianapolis would rain down boos on a commissioner who went out of his way to fly to Indiana to pay tribute to Manning. When Roger Goodell is booed in these environs, in front of a crowd ready to shower nothing but love on the dais … well, I am dubious, for as long as he is on office, whether he’ll ever rehab his public reputation.

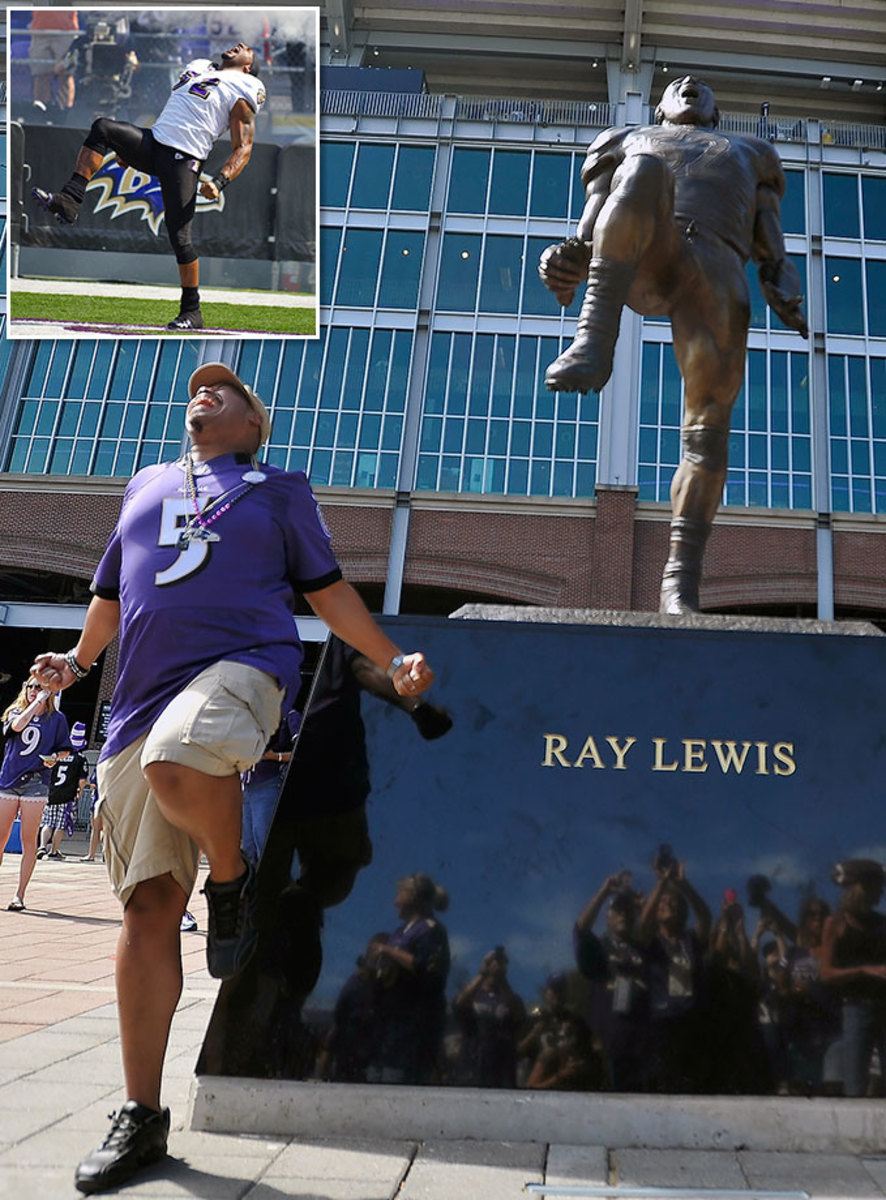

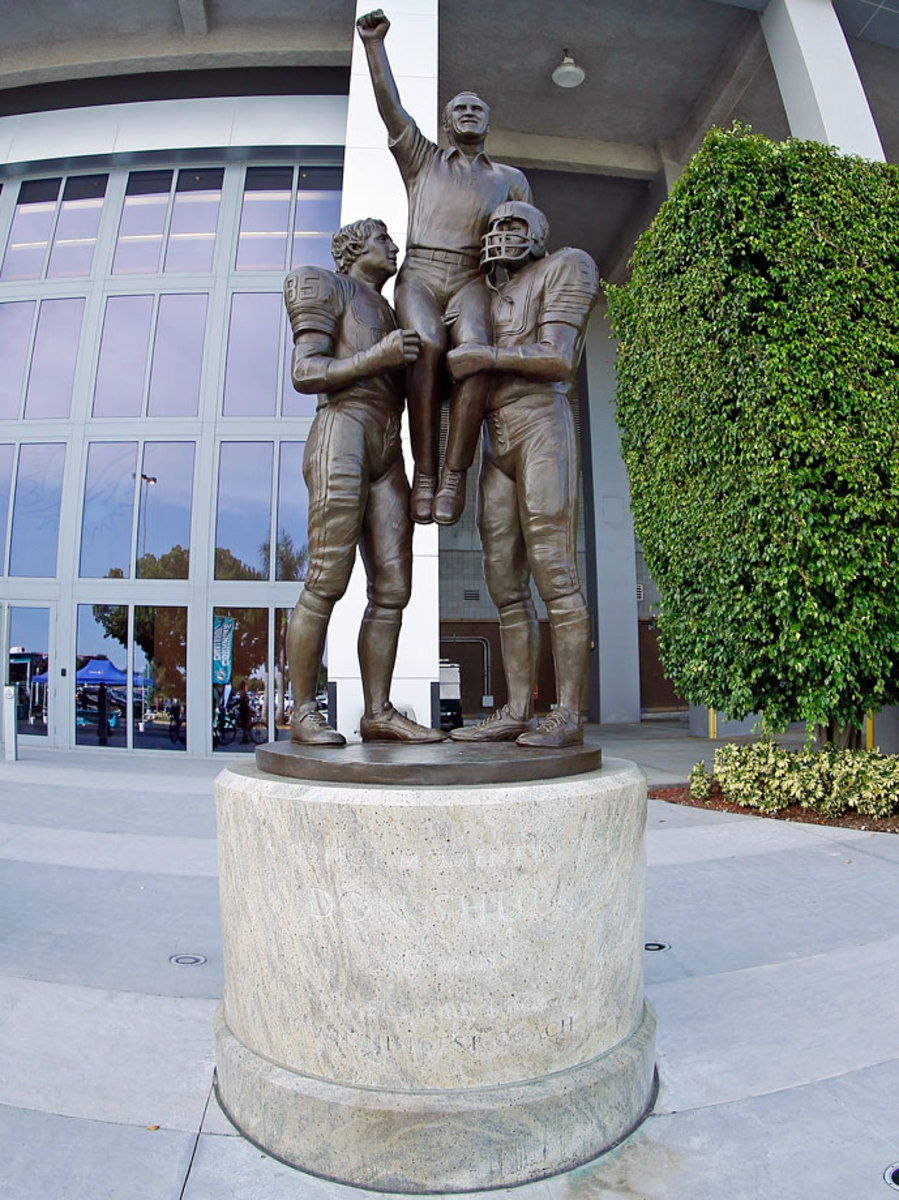

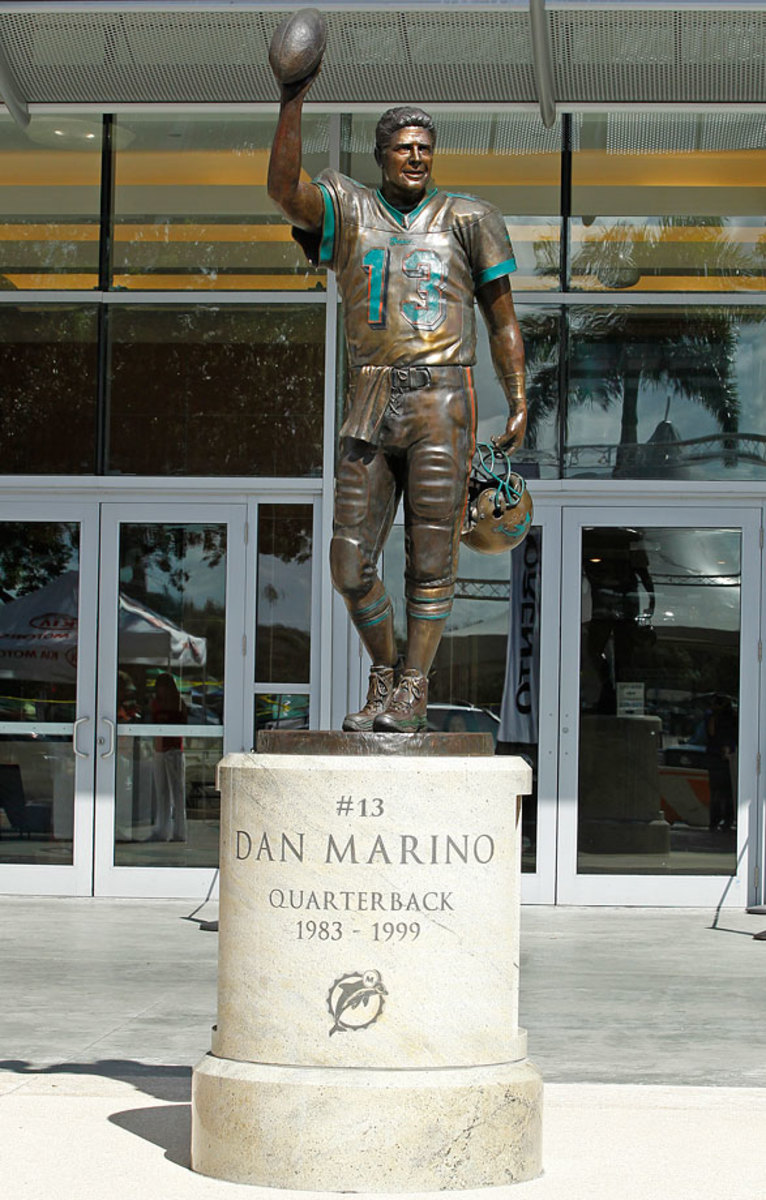

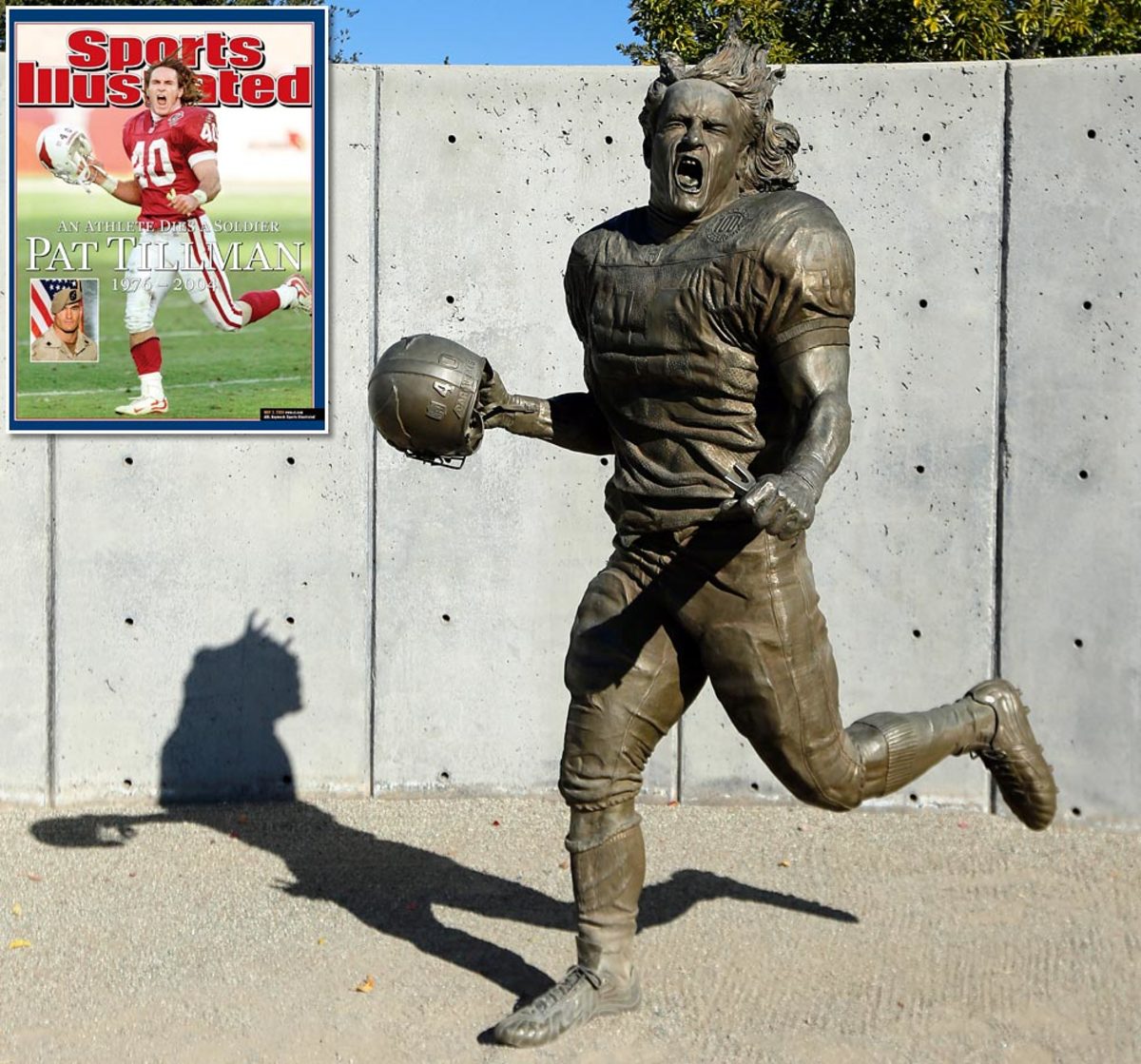

• Teams should build these statues and have these ceremonies more often. The Cardinals did it with a statue of the late Pat Tillman at their new stadium. The Dolphins did it with Dan Marino, the Ravens with Ray Lewis. The Niners should build a Joe Montana statue at their new ballpark and let the fans pay their adoring respects. Ditto Cleveland with Jim Brown, Pittsburgh with Chuck Noll, Denver with John Elway, Dallas with Roger Staubach—and maybe with a triplet statue of Aikman, Smith and Irvin. For years, folks will stop in the northeast corner of the plaza outside Lucas Oil Stadium, and fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, will take photos with the Manning statue, and those photos will go on walls and desks and mobile phone backgrounds, and not just in Indiana. Whatever the cost, it’s worth the current and future goodwill.

Statues Around the NFL

Jerry Richardson

Bank of America Stadium in Charlotte, N.C.

Peyton Manning

Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis

Ray Lewis

M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore

Johnny Unitas

M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore

Don Shula held in the air by Nick Buoniconti (left) and Al Jenkins

Sun Life Stadium in Miami

Dan Marino

Sun Life Stadium in Miami

Art Rooney Sr.

Heinz Field in Pittsburgh

Vince Lombardi and Curly Lambeau

Lambeau Field in Green Bay, Wis.

Lamar Hunt

Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City

Tom Landry

AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas

Pat Tillman

University of Phoenix Stadium in Glendale, Ariz.

• Manning finished his career in Denver with another Super Bowl, and he lives there now. He was ticked off when the Colts moved on from him in 2011, but six years healed every wound. Manning got emotional talking to the crowd. The crowd—at least via signs from as far west as Hawaii, as far east as New Jersey—ladled love on him for an hour. “WE LOVE YOU MAN,” punctuated the affair three times from the crowd. A friend of mine, Angie Six, was in the middle of it and texted me afterward: “Being a part of the crowd was a truly moving experience, enough to make this fan and those around me a little misty-eyed. Standing shoulder to shoulder in the shadow of Lucas Oil Stadium, I saw a diverse crowd of Colts fans: young, old, black, white, Hispanic, men, women. We are all Hoosiers, proud to claim Peyton as our own. When Peyton left to play for Denver, we watched heartbroken from afar. We never had a chance to say thank you. Today we were able to express our gratitude in person, and the crowd was giddy. The woman behind me said, ‘What a great day to be a Colts fan.’”

• And for the record … It’s not just the business community that benefited from the effect of Manning. The Indianapolis area has $63 million worth of reasons to be grateful: $13 million from grants issued over the years through Manning’s foundation, and $50 million in money raised for the children’s hospital in Indianapolis that bears his name.

Football in America: Episode 3—Minneapolis-St. Paul

We started our series (in partnership with State Farm) examining all levels of football—youth, high school, college and pro—with visits to the Bay Area and Charlotte. For the latest installment, Robert Klemko, Kalyn Kahler and videographer Steve Raum take us to Minneapolis-St. Paul and weave a tale of close-knit communities and the meaning of football there.

Football in America: A Family Game in Minnesota

In the tiny town of Cleveland, Minn., 66 miles southwest of the Twin Cities, The MMQBteam finds a nine-man football game, the aroma of nearby pig farms wafting over the field. The head coach, Erik Hermanson, doubles as band director. From Klemko and Kahler: “After the final note of the anthem (for which all stand), Hermanson waves his band off the field and jogs over to the sideline, where the Clippers are lined up and waiting. Normally, quarterback Carter Kopet plays trumpet and his prolific receiver, Austin Plonsky, plays trombone, but not tonight. An assistant coach hands Hermanson a headset and a clipboard. Because in a town as small as Cleveland, the band director is also the co-coach. Hermanson, who has coached the football team in Cleveland for 22 years and directed the band for 24, says he’s never been tempted to leave for a program with 11-man football: “I always wanted to be a head coach, and I've always wanted to be a band director, and there aren't many schools you can go to where you could do both.”

Then we get into P.J. Fleck, and the youth game in the inner city, and the Vikings. We’re having a ball taking you across the country and showing you football America.

Coming this week: Dallas-Fort Worth, where Jenny Vrentas and Kahler see a blend of big-time Texas high school football, college football and the Cowboys. The high school portion will be great—Americana, a great dance team, and a very diverse football roster.