The ‘Worst Game’ in NFL History Was the Best Game Lawrence Taylor Ever Played

Brian McClure was sitting in the quarterbacks meeting room, running through the Bills’ game plan on Wednesday, October 14, 1987— exactly 30 years ago this week. It was nearing the end of the NFL players’ strike, but in four days McClure, Buffalo’s replacement QB, was set to make his first professional start, against the Giants. Then a coach came bursting through the doors breathless, with an update. Lawrence Taylor, the Lawrence Taylor, had just crossed the picket line. Yes, the coach said after the inevitable follow-up question. Taylor would be suiting up on Sunday.

In that moment, two words came to McClure’s mind:

Oh shit.

McClure was a standout athlete in the small town of Ravenna, Ohio, population around 10,000, an accidental quarterback who wanted to play receiver but weighed about 175 pounds in high school and happened to have a strong arm. He went on to Bowling Green, where he led the Falcons to an undefeated season in 1985 and set school records in completions, passing yards and touchdowns. He was selected by the Bills in the 12th round of the 1986 draft, spend his rookie season on injured reserve and then got cut in training camp in ‘87. So he went back home to Ohio, his football career on hold.

A few weeks later the NFL strike began, and Bob Ferguson, the Bills’ director of player personnel, came calling. At first McClure hesitated, not wanting to cross a picket line of NFL players. But after two weeks of watching Buffalo lose back-to-back replacement games, McClure reconsidered. He had been spending his days thinking about his rapidly diminishing career options. After being cut, he had gone to Green Bay for a tryout and wasn’t signed. The Houston Oilers expressed interest but never brought him in for a visit. He knew he wouldn’t have many more NFL opportunities. But he was also friends with quarterbacks Jim Kelly and Frank Reich and was worried about their reaction if he crossed. McClure was torn. This would be his best, and maybe his last, chance to show teams around the league what he could do. So hwe agreed to return; he would be the Bills’ starting QB, effective immediately.

“I was doing what was best for me,” he says. It was one more chance to play a sport that he loved. One more opportunity to prove that he could compete in the league, to get another look.

“I just didn’t know it’d be against LT.”

Sean Dowling had been a Giants fan his entire life. The offensive lineman grew up on Long Island, went on to play at C.W. Post, a Division II school that dropped down to Division III during his time there. While he was in college he also joined a semi-pro team, the Brooklyn Kings. After he graduated, he switched to a higher level semi-pro team, the Connecticut Giants; when the strike began, many of the Connecticut Giants were brought onto the New York Giants as replacement players. But, for whatever reason, Dowling was not.

Then one day he got a call from Andy Ellison, the Connecticut Giants’ coach, who said that the Bills were in search of an offensive lineman. At the time Dowling was working odd jobs and still taking classes to finish his degree. So, yes, of course he was interested in joining an NFL team. The next day he met Ellison in the parking lot of a movie theater. He signed a contract and was on a plane to Buffalo the next morning.

“To me,” Dowling says, “it was a tryout.”

On the first day the new Bills were brought to the facility, the real Bills were waiting in the parking lot, picketing. One of the replacement players made the unwise decision to snap pictures of the scene out the window. That’s when the Bills outside started to throw eggs at the bus. Still, Dowling remembers enjoying the first couple of weeks with the team. There were new faces coming to the facility every day, guys from all over the country, with all sorts of jobs and backgrounds and stories. And they all just wanted one more chance to play football.

“We all took it very seriously,” he says. “There were guys like me that thought, This is my tryout. And then there were guys that thought, This is my last, only shot at glory.”

Dowling started the Bills’ first two games, at right guard in a 47-6 loss to the Colts, and at tackle in a 14-7 defeat to the Patriots. But he believe the team was just starting to come together; they felt confident going into the third game, against the Giants. Then, on Wednesday, as he was walking out of the locker room to head back to the team hotel, Dowling was stopped by Bills coach Marv Levy. The coach knew that Dowling had always been a Giants fan.

“Well, Sean,” Levy told the lineman. “I have some good news and some bad news. The good news is that Lawrence Taylor has crossed and will be back playing for the Giants. The bad news is that you’re going to have to block him.”

Dan DeRose was teaching microeconomics when the Giants called. Professor DeRose had played linebacker at Colorado before he transferred to finish out his collegiate career at Southern Colorado just a few years earlier. He founded a semi-pro team in 1986 called the Pueblo Crusaders, where he also served as the team’s head coach and middle linebacker. After he finished his MBA, he became a professor at his alma mater; in the fall 1987 he was teaching five classes: micro and macro economics, two marketing classes and international banking. Then one day his office phone rang.

The voice on the other line said that he was with the New York Giants and that he wanted DeRose to join the team. The professor thought it was a prank call, another one of the teachers screwing with him, and nearly hung up. Then the caller got irritated and told him that this was serious, that he needed an answer, and that he needed one immediately. DeRose responded that he was in the middle of mid-terms and wasn’t sure if he’d be able to leave. Then the salary was mentioned. DeRose doesn’t recall the exact figure but it was enough for him to say:

“What time do you need me there?”

DeRose was admittedly not a union guy, so he had no hesitation about crossing the line. He also had no grand vision of ever playing in the NFL again, of his replacement career turning into a real career.

“I wasn’t one of those guys,” he says. “I just knew it was going to be a whole lot better than teaching microeconomics.”

After he hung up, DeRose went to speak with the school’s dean to explain the situation. Then he found another professor to cover his classes and boarded the first flight to New York he could find. The Giants set him and all the replacement players up at the Sheraton Hotel in Hasbrouck Heights, N.J. Unlike most of the other teams in the NFL that had entered into pre-emptive agreements with players who were cut in training camp, saying they’d return in the event of a work stoppage, the defending Super Bowl champion Giants did not plan ahead. Possibly because they didn’t want to upset their players, or possibly because they didn’t have the foresight that a strike was imminent, the Giants were forced to scramble after the fact, bringing in an eclectic group of semi-pro players like DeRose. Their replacement roster ended up having only three players with any NFL experience.

“We had a rag-tag unit,” he DeRose says. “But I think everybody had the same attitude. We don’t know if this is going to last a day or a month, but we’re going to have a ball while we’re here.”

Not everyone had a ball, however. DeRose remembers Giants coach Bill Parcells not being very enthused to coach a bunch of replacement players. (“He wasn’t in a great mood, but I don’t know if he’s ever in a great mood anyway.”) But he also remembers defensive coordinator Bill Belichick embracing the moment, dumbing down the defense and eagerly teaching the replacement players from day one. (“He wanted to win. He didn’t care that we were a scab team. To him it was about trying to out-strategize the other guy.”)

The economics teacher started the first two games for the Giants at middle linebacker, and was named the defensive captain of the replacement squad. Like Buffalo, New York lost both of its first two games: a 41-21 drubbing by the 49ers on Monday Night Football, and a 38-12 clobbering by Washington. The Giants’ defense was weak, unable to stop anyone. Then Taylor returned.

He was friendly with the replacement players but stayed mostly to himself. Besides, he was Lawrence Taylor, and they were not. DeRose recalls LT sauntering in late to meetings. The team would fine players for each minute they arrived late—DeRose vaguely remembers it as $100 a minute. Taylor would show up six minutes late, the coach would tell him that’ll be 600 bucks, and Taylor would simply respond “put it on my tab” and sit down.

But despite playing against a bunch of so-called scabs, LT was as crazed, as intense as ever. In his first practice he broke a blocker’s wrist with a spin move.

“Football was his refuge,” DeRose says. “And he was destructive.”

Bob DiRico was going to be a teacher. He had just registered for his last semester of classes, set to finish his degree in elementary education at Kutztown, where he had rushed for 2,057 yards and was an honorable mention All America. With 20 credits left to graduate, he enrolled in an elementary education mathematics course and a mandatory music class and began his student teaching obligations. Then Ray Handley called.

The Giants’ running backs coach laid out the situation. The strike is happening and the team was reaching out to players whom they had in training camp— DiRico had been signed as an undrafted free agent by the team earlier that year and had been cut three weeks into camp. After the call, he hung up, walked over to the registrar’s office and withdrew from school. A second chance to make a first impression, he thought.

(A quick aside: When DiRico was originally cut from Giants training camp, he was summoned to Parcells’s office and told to bring his playbook. The coach went through his spiel, a sort of pep talk to the departing player. Parcells told him that he had done a commendable job in camp, but they were the defending champions and it was tough for even their top draft picks to make the roster. Just as he was wishing DiRico the best of luck in his career, the running back, jittering with nervous energy, cut Parcells off. “Do you know how to get back to the turnpike from here?” he asked the famously ornery coach. Parcells appeared confused. “I know the area, Bob,” he responded. “I would take Route 80. Actually, let me write it down for you … ” Then he took out a yellow sticky note, jotted down the directions and handed it over. “In disgust, since I was mad at the time, I threw out the directions,” DiRico laments. “Would have been a good souvenir.”)

DiRico hadn’t even thought about returning to the NFL after he was cut. He figured his career was over and he might as well get on with his life. But now, he thought, he had another shot, especially after the first week of replacement practice, when the team’s top back got injured. On Friday DiRico was notified that he would be the starter in the first replacement game, the nationally televised Monday nighter against the 49ers. All weekend he was nauseous, the three-day wait feeling like six months.

In the locker room before the game Parcells told the team that once the strike was over, there was the chance that upwards of 15 replacement players could be signed to the regular roster. DiRico felt like he was going to puke. This is my shot, he kept repeating to himself, this is my shot. Then he got on the field, the game started, and he had five carries for 11 yards, fumbled once, and was promptly benched by Parcells. I blew it, he kept repeating to himself, I blew it.

Against Washington in the Giants’ second replacement game, DiRico didn’t get a single carry, so entrenched was he in the Big Tuna’s doghouse. But he came up with three solo tackles on special teams and thought maybe special teams coordinator Romeo Crennel would put in a good word with Parcells, maybe he’d get another shot in the Bills game.

When LT showed up mid-week before the trip to Buffalo, DiRico was one of the few players who had previously met him from his time in training camp. He remembers how Taylor generously let two rookies whom he did not know borrow one of his luxury cars— a BMW or a Porsche, DiRico isn’t sure—to drive back home to Connecticut to visit their families. The running back also remembers the time he had to line up against Taylor in a one-on-one blocking drill and was expecting to be bull-rushed. If I just get a piece of him, DiRico thought, I’d look like a hero. Then Taylor came flying around the edge and put a swim move on the running back, blowing past him on the way to the QB.

“Honest to God, I didn’t get a hand on him,” DiRico says. “Not even his shirt.”

DiRico remembers how Taylor joined him in the offensive meeting room at points during the week leading up to the Bills game, as the team had implemented a passing play into their game plan specifically for the linebacker. On Saturday morning, the day the Giants were set to travel to Buffalo, Taylor returned to the facility at 8, emerging from a stretch limousine in a tuxedo. He had just gotten back from the Mike Tyson-Tyrell Biggs heavyweight title fight in Atlantic City and had been out all night. That was something they hadn’t seen, that was cool. Again, he was Lawrence Taylor and they were not.

“He changed everything,” DiRico says.

Todd Schlopy was on the slopes, teaching kids how to ski race, a placekicker who’d grown disillusioned with football. There were only 28 NFL teams at the time, so that meant there were only 28 jobs for kickers in the league. Schlopy had been in and out of training camps for a few years, and although he kept coming closer, he had been unable to make a final roster. And, unlike the minor league system in baseball, he lamented that he had nowhere else to play.

Schlopy grew up in Orchard Park, N.Y. (where the Bills’ stadium resides), kicked at the Michigan and graduated in 1984, undrafted. However, he knew Bills assistant head coach Elijah Pitts, whose son Ron, a defensive back on the team, was one of Schlopy’s best friends from high school. The elder Pitts invited Schlopy to Buffalo’s training camp in ’85, where the kicker was beaten out by Scott Norwood. The following year Schlopy lost a job to veteran Norm Johnson at Seahawks camp. In ’87 Schlopy was back in Buffalo and, again, was bested by Norwood. This time, however, as he was packing up his belongings in the locker room, Bills coach Marv Levy approached. Something is going on here, Levy said, and you should go upstairs because management wants to talk. Upstairs, front office executives offered Schlopy $5,000 if he would sign an agreement that stated, in case of a players’ strike, the kicker would come back to the Bills. Schlopy took the cash.

“I wasn’t trying to prove a point,” he says. “I never in a million years thought the players were going to go on strike.”

When Schlopy reported to the Bills after the strike, he remembers there being a tremendous amount of animosity from the regular players. At one point, in the lobby of the hotel that the team had placed the replacement players in, one of the Bills’ regular players showed up with two dogs and confronted a group of the scab players. It got so heated that one of the replacement Bills had to climb on top of a vending machine to find refuge.

Schlopy didn’t attempt a single field goal in the team’s first two games. His third game would be back in Orchard Park, his hometown. His dad would be in the stands that day. As would Ron Tipps and other assorted friends and family members. Schlopy went into Sunday afternoon as excited as any game he could remember. Not even the looming presence of Lawrence Taylor could dampen his spirits.

Phil McConkey, the Giants most unlikely Super Bowl hero a year prior, also grew up in Buffalo and had the Week 5 game against the Bills circled on his calendar for months. Literally.

In Super Bowl XXI, McConkey etched his name into Giants lore with a momentum-shifting 25-yard punt return, a 44-yard reception on a flea-flicker and a fourth quarter coup de grace touchdown catch that is still fondly remembered in franchise history. McConkey, though, still viewed himself as expendable, a day-to-day player who could be cut at anytime. So when he saw a trip to Buffalo on the calendar at the beginning of the season, out came the pen, marking the day. He had attended the first-ever game at Rich Stadium in 1973; this would be his first time getting to play there. He didn’t know how many more chances he’d have.

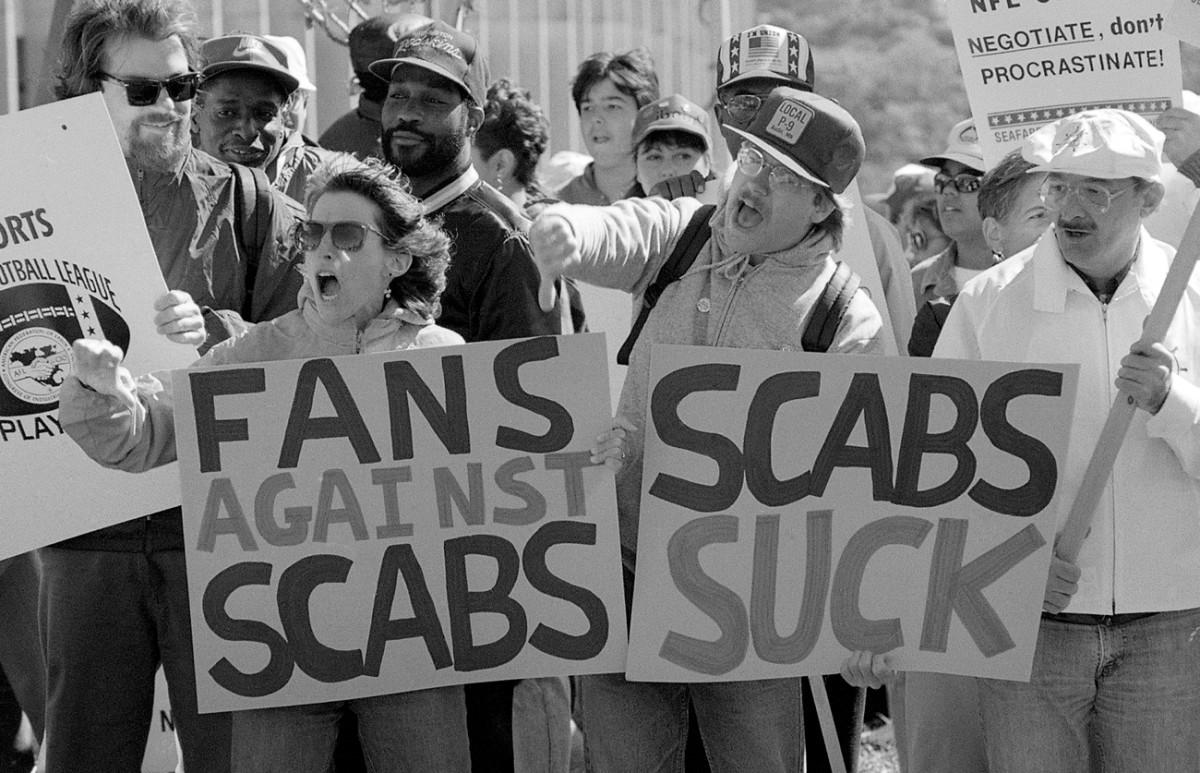

“I was very much looking forward to playing [in that game],” McConkey says. But he’d never get to. After the second week of the season the players went on strike,

“It is one still one of the biggest regrets of my life,” he says.

The possibility of a strike had been discussed by Giants players in private after the CBA had initially expired in August before the regular season began. McConkey remembers linebacker Harry Carson and defensive end George Martin standing in front of the team, writing out a list of the players’ collective grievances on a chalkboard. On that list were many issues that the “average worker could relate to”— as McConkey put it. Things such as better retirement benefits, improved healthcare, better severance pay and educational training, “the types of things that would be helping guys in their 50s, 60s and 70s.” The issue of free agency was ranked seven out of the nine issues the players enumerated.

Then the strike began, and it soon became clear that the NFL’s union—which is “not as organized, not as cohesive a union as some of the other sports,” as McConkey says— had centered their protest around free agency. McConkey was confused. That was not an issue that would benefit the vast majority of the players in the league.

“The things that we thought we were striking for were, the things that we voted on, were not the main issues of that strike,” McConkey says. “I wish we had held out for some other things that would be helpful to the retirees today, because a lot of guys are hurting, a lot of guys are suffering.”

When the strike began, McConkey was torn. He was a football player. He wanted to play football. But his whole life he had been taught that teammates stick together, that it is us against them. “As much as I wanted to cross that picket line,” he says, “I was a team guy and it was hard for me to do that.”

Even when he saw LT cross, he knew that he wouldn’t be able to follow suit.

“Lawrence Taylor can cross the picket line and what are they going to do to Lawrence Taylor?” McConkey says. “But one of the last guys on the roster? It’s tough. LT could do whatever he wanted because he led by example and played every play with his pants on fire. He was the greatest teammate ever.”

McConkey watched from his couch as Taylor and the Giants traveled to his home town to play the Bills. He remembers thinking one thing.

Man, I’d love to be right there with him.

Lawrence Taylor doesn’t want to rehash what went through his mind when he crossed the picket line. That was a long time ago. But he will say this.

“I’ve been rich, and I’ve been poor,” Taylor said via email. “And I like rich a helluva lot better. And losing whatever the F I was making per game check … stung.”

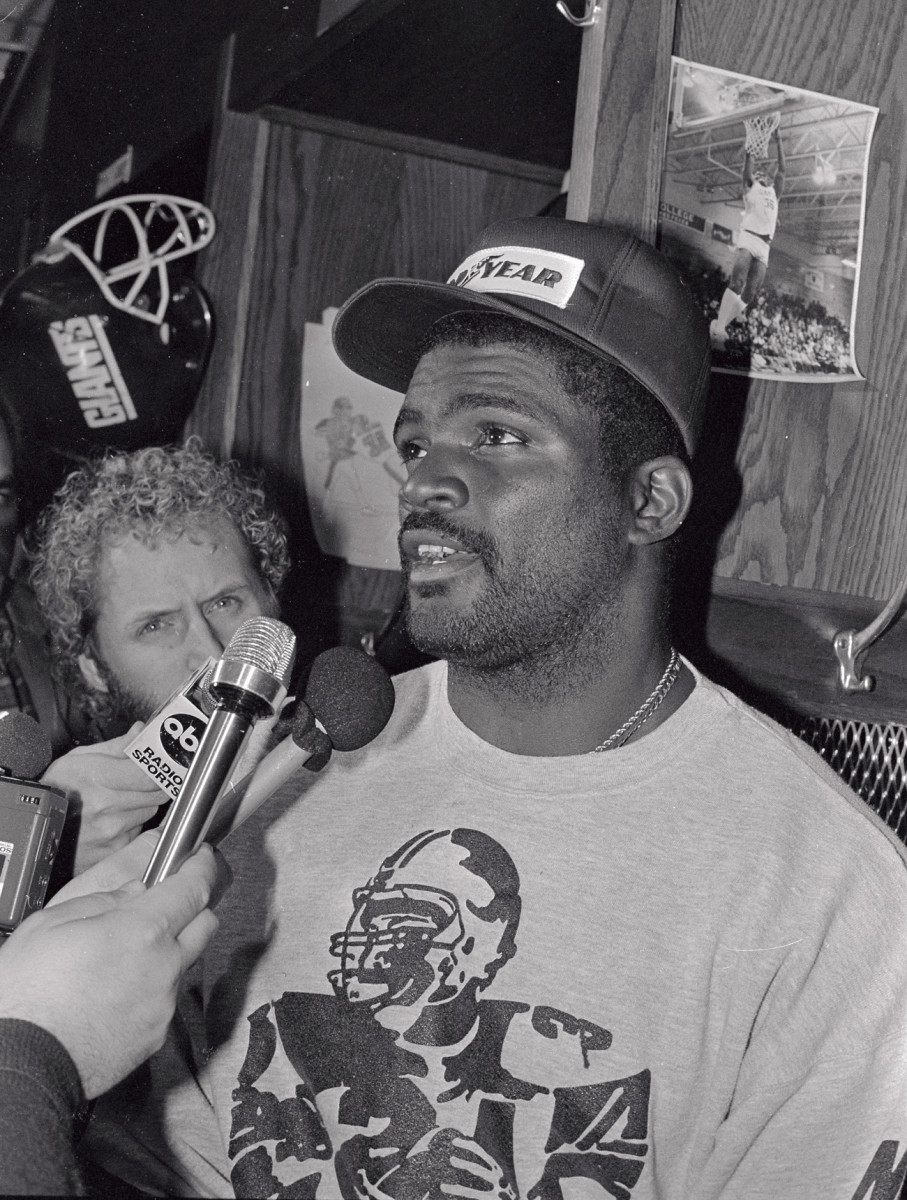

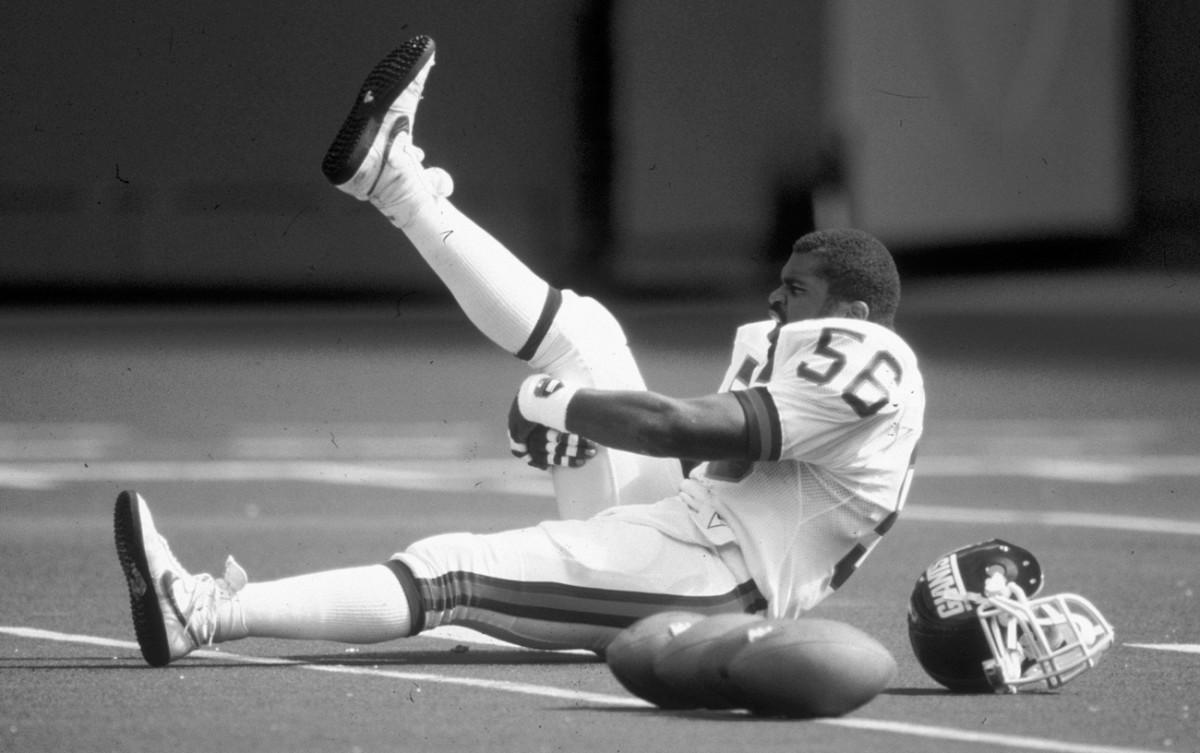

In 1986, Taylor led the NFL with 20.5 sacks and was named the NFL Defensive Player of the Year. He had already transcended the game of football, was already regarded as one of the greatest defensive players of all time. “Having Lawrence Taylor is like planned havoc,’’ Len Fontes, the Giants’ defensive backfield coach, said at the time of his return.

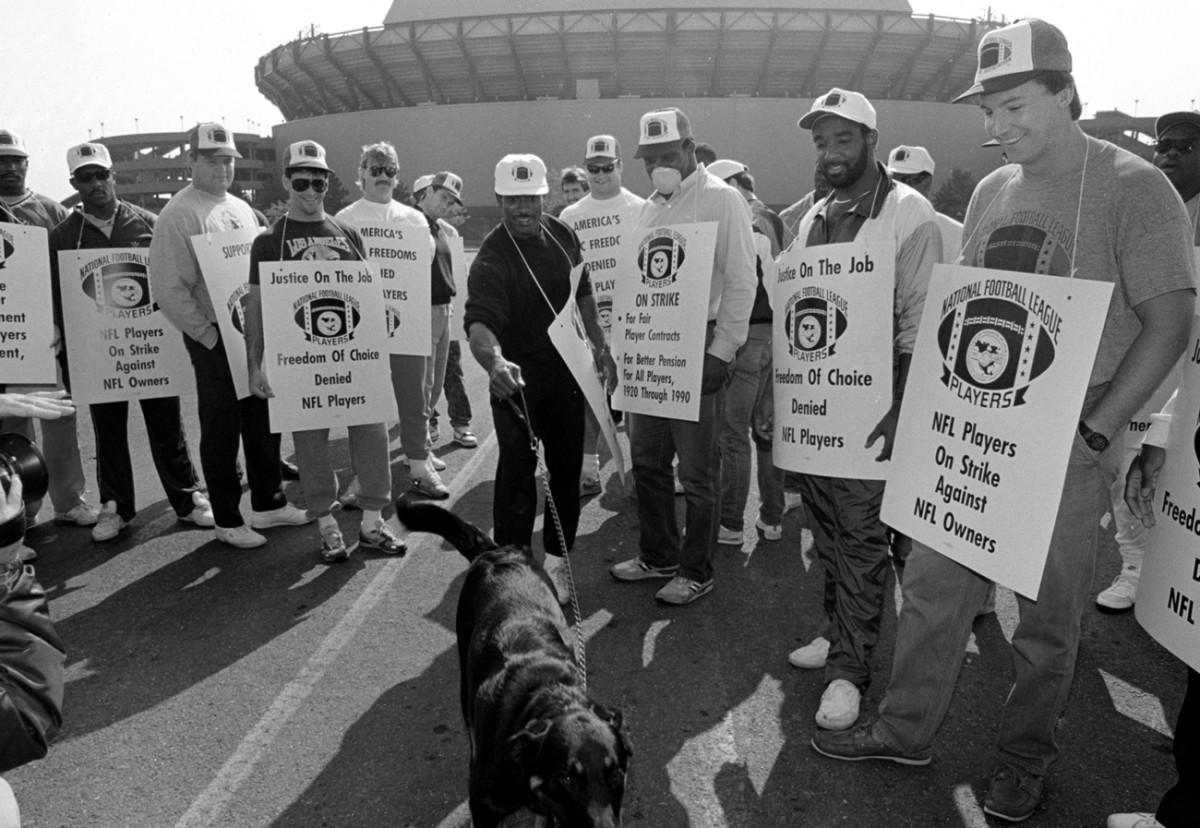

Taylor rejoined the Giants on Wednesday. The strike officially ended the following day, the players union capitulating on all major issues. But the league decided that only the players who had crossed before the union folded would be allowed to play in that weekend’s games. It was another decisive, devastating labor win for the NFL owners. Preventing the players from participating in the Week Five games—dubiously citing concern for injury after their extended time off—and thus keeping another week of pay was the final flourish.

Heading into the weekend, the replacement players were told that this would be their final game; they understood there would be no tomorrow. So Taylor says he didn’t waste much time getting to know his teammates during the half-week that they practiced together.

“I knew they weren’t sticking around too long,” he writes. “I’m not and never have been, the type for idle chatter.”

The Giants had lost their first two replacement games by a combined 46 points. The defense had allowed 79 points and 809 yards in two games. New York was 0-4 on the season, after coming into the year with hopes to repeat as Super Bowl champions. The replacement squad was in disarray; Taylor wanted a win to revive their season. He says that Parcells didn’t say much to him upon his return, because, well, he didn’t have to.

“We both knew it was a mess,” Taylor writes.

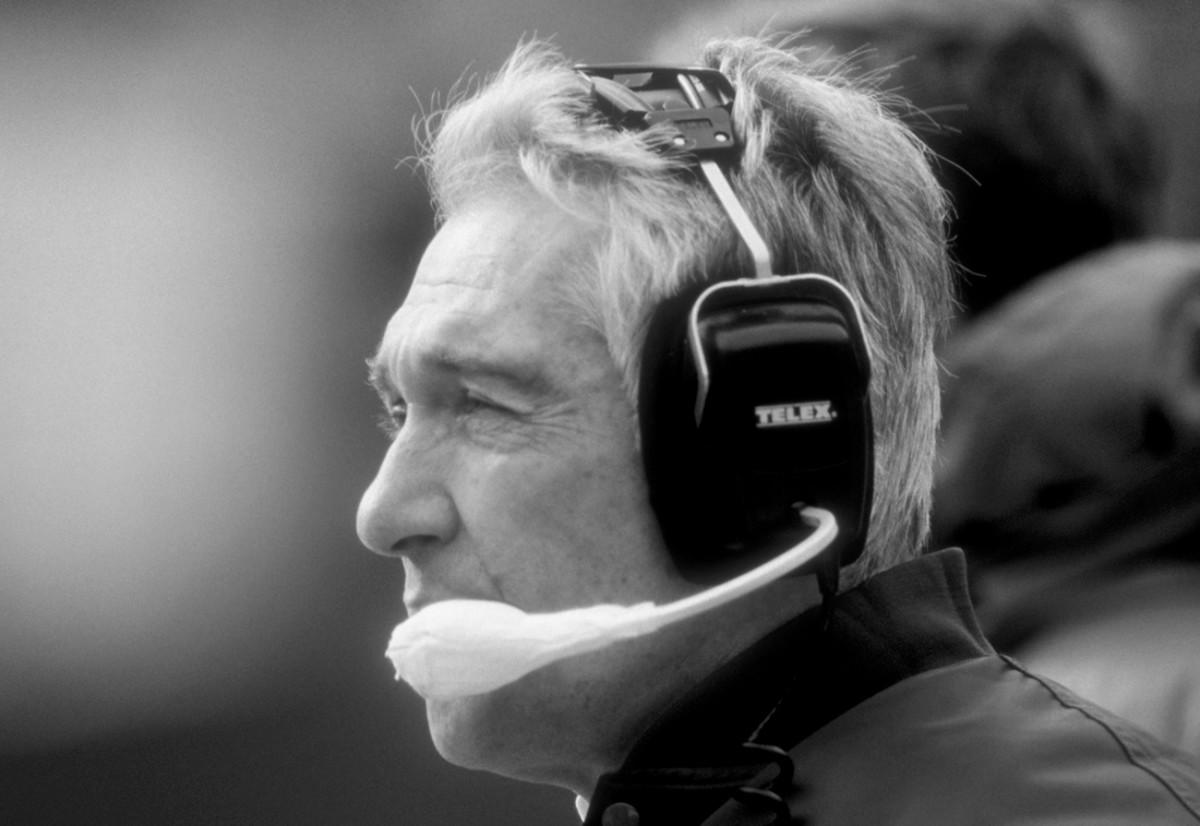

Marv Levy called it the worst game he had ever seen. That was back in 1987, after the game ended.

“That is probably true,” Levy says now. “It is still that.”

Levy had taken over the Bills in the middle of the 1986 campaign, making ’87 his first full season with Buffalo. For him, as he says, that year was “a bit unnerving.” Here he was, a rookie head coach, coming to a squad with Jim Kelly and Andre Reed and Bruce Smith, anticipating a very successful season. Then the strike happened, and he had none of those players at his disposal. Actually, he didn’t really know any of the players he had.

“We had about four guys that were just fill-in players, young players, all with the last name Jones.” Levy said. “One was Darrell, one was Darren, one was Donny, one was Donnell, and I couldn’t figure which one was which. But one of them, no matter what you did, if you chewed him out or anything, would just say ‘thank you.’ So we named him Thank You Jones.”

When the news came down that Lawrence Taylor would be returning, and Levy would have to attempt to thwart him with a bunch of guys named Jones, Levy told The New York Times that he was not going to adjust his blocking plans. ‘‘We don’t make personnel plans during these replacement games,’’ he said to the Times. ‘‘The players are struggling to learn their assignments.’’

Asked now what his first thoughts were at that time, Levy says, “I don’t remember any other reaction other than raising my eyebrows and then going back to work. You have to be prepared for everything as a coach.”

How does one prepare a bunch of replacement players to face Lawrence Taylor?

“Well…” Levy says. His voice trails off.

It was about 50 degrees at the time of kickoff, slightly damp, with swirling winds. Before the game, Parcells had noted to reporters that he knew the Bills would be focusing all their attention on LT, trying to mitigate his impact. “But they’ve got to find Lawrence first,” Parcells said wryly.

In fact, Taylor was lined up all over the field, given pretty much free reign to cause havoc however he deemed fit. He didn’t learn many, if any, of his provisional teammates’ names. So he took to calling Dan DeRose “Boss Man.” And since DeRose was the defensive captain, and Taylor wasn’t all that familiar with the new dumbed-down defense that had been installed for the replacement players, it was DeRose who was still receiving the play calls from Belichick and relaying them to Taylor and the other defensive players in the huddle.

“So we would break the huddle and [Taylor] would say, ‘Boss Man, what do I got?’ ” DeRose says. “And I’d say ‘Lawrence, you got C-gap outside, pass you got the flat.’ ”

“Okay, Boss Man,” Taylor would reply, and then he’d go out and do the things that Lawrence Taylor was known to do.

“He’s making almost every other tackle,” DeRose says. “Eventually I just said, ‘Lawrence, you’re going to go to the Hall of Fame, you’re going to Canton. I’m going back to Colorado and teaching economics, do whatever the hell you want to do, and we’ll just fill in.’”

Dowling started at right guard for the Bills, and on one of the game’s first plays he had to pull to his left on a running play. Before the snap, he had been watching Taylor doing the typical Taylor gesticulations and exhortations, and when Dowling pulled left and looked up, Taylor was the defender in front of him.

“I go, Holy crap I have to block him, that’s the guy I got to block,” Dowling says. “I take a step and I have him lined up. I take another step, eh, I don’t have him lined up so much. I take another step, I’m chasing him.”

Taylor drew seven holding calls in the game, but Dowling wasn’t responsible for any of them. Four were on Bills center Will Grant and three on left guard Rick Schulte. Levy remembers pulling Grant aside on the sideline at one point during the game to discuss the mounting penalties.

“I said to him, ‘Will you’ve been called four times for holding,’ ” Levy remembers. “And he said, ‘Coach that’s good, I’m holding him every down.”

Taylor agrees with that assessment. “They could have called holding on every f’ing play,” he emails. “In fact I vividly remember the umpire telling me: ‘Hey, you’re going to have to fight through it, cause we can’t call it on every play … [But] I never had a problem with a backyard brawl.”

It was Schulte, however, who was the one who made headlines the next day for his rough and physical—and, by all accounts, dirty—play. Schulte, who died of a heart attack in 2008, was a guard who had played at Illinois. Small and stocky and able to bench press more than 500 pounds, Schulte had no hesitation squaring off against Taylor.

“Rick Schulte was not afraid of, nor did he fear, anyone,” said Don Passmore, Schulte’s college teammate and best friend. “Rick was not in awe of anyone on the football field. He played until the whistle and beyond, and that’s what kind of pissed LT off.”

At one point, as Taylor rose from the turf, Schulte dug his knee between the linebacker’s face mask, seemingly in an attempt to break his nose. Taylor ended up with two sacks in the game and countless more hits on McClure, a disruptive performance that Giants owner Wellington Mara later called the best of Taylor’s career. Throughout the game, McClure could hear Schulte jawing back and forth with Taylor and would see him hitting LT after the whistle. The quarterback wasn’t enthused; as the linebacker got more frustrated with the late hits, he would take his anger out on the QB.

Taylor got so fed up with Schulte’s antics that, late in the game, he ran over him, took his fist and “drove it right down his throat”—Taylor’s words at the time. Then he rubbed the fist in and said, “How do you like that sucker?” When asked about that now, Taylor does not dispute the events.

“Yea, late in the game I had had enough,” Taylor writes. “And I basically tried to take his head off. He got the point.”

The game itself was ugly. The two teams combined for nine points, total. They matched that number in turnovers. DiRico did get his chance at redemption, after the Giants’ starting back fumbled in the first quarter and was benched, bringing the Kutztown back out of Parcell’s doughouse. He finished the game with 79 yards rushing on 20 carries—he likes to round it up to 80, so it’s 4 yards per carry—and 22 receiving yards. DeRose had one interception, which he returned for 10 yards. McClure finished with 20 completions on 38 attempts, for 181 passing yards, each number the most in NFL history among players who only played in one career game.

The two teams went into the fourth quarter knotted—at zero. After a field goal apiece, the score sat at 3-3. With 10 seconds remaining, the Giants had the ball on the Bills’ 23, and it was time to use their newly installed secret play. So out came LT, lining up at tight end. And it worked—almost. The pass was tipped and flew over the hands of a leaping Taylor in the end zone. ‘‘God, I was wide open,’’ Taylor said after the game.

Eventually the teams sputtered their way through overtime until, mere seconds from finishing in a tie, Todd Schlopy lined up a 27-yard field goal to win the game. The Giants called a timeout to ice the kicker. The players all loitered around the field, waiting for play to resume. “The things Lawrence Taylor was yelling at me about my mother, I can’t repeat,” Schlopy says.

He had already missed three field goals in the game, two coming after botched snaps. Schlopy’s dad left the stadium before the final kick, too nervous to watch.

“I told [holder] Dan Manucci, ‘Just put it down, I don’t care where the laces are,’” Schlopy says. “And then I had one of the best kicks I ever hit. And it turned out to be the last kick I ever hit.”

Bills 6, Giants 3.

The hometown kicker became an unlikely hero. After the game Schlopy traveled around to all the late-night talk shows in Buffalo, sitting down with the sportscasters he had grown up watching. “If you’re talking about your 15 minutes,” Schlopy says, “that was it.”

McClure’s wife was waiting for her husband in the tunnel after the game when she came face to face with Taylor. The linebacker was wearing a black leather jacket, no shirt underneath, and his typical, scowling visage. McClure’s wife began to cry hysterically at the sight, simply because he looked so angry and had been beating up on her husband all game.

“She was just in fear for my life,” McClure says. “We hauled out of there.”

The quarterback would be placed on injured reserve the following week— after four days spent primarily in the whirlpool—with what he called “total body-ache.” He was one of the few replacement players not cut immediately. On the field after the game, Taylor sought out Schulte; he called him a “cheap bastard” but also, reportedly, shook his hand and told him that he respected him. Some tellings—including in a 1992 Sports Illustrated story by Peter King—make Schulte out to be nervous and deferential when confronted by LT after the game. Terry Schulte-Scott, the guard’s sister, would like to correct that narrative.

“The first wrong to right is that my brother was not intimidated by anything, ever,” she says. “I remember Ricky laughing, a couple of years before he died, as he was reading some article. And one of the things that Lawrence Taylor talked about in his career was when that guard Rick Schulte tried to break his nose.”

After the game the replacement players would go their separate ways, returning to normal lives, connected through the years only by this one shared experience. DeRose went back to Colorado to teach his economics courses and to join his Pueblo Crusaders, who were making a playoff run; in 2006, he would sell a chain of dental clinics for $435 million. DiRico returned to Kutztown to finish his teaching degree, eventually switched fields and became a business development representative for Aiphone, a company that makes video security systems and other telecommunications products. Schlopy returned to ski racing, both competitively and as a coach, moved to Park City, Utah, and, with a film degree from Michigan, began a career as a Hollywood cameraman—his credits now include Fast and the Furious 7 and The Revenant. McClure moved back to Cleveland with his wife, got a job in the public works department, coached youth football and started a family; his older son, Kade, was just selected in the sixth round of the MLB draft by the White Sox. Dowling bounced around a few more semi-pro teams and then moved to New Jersey and got into teaching and coaching both football and lacrosse; he is now the athletic director of Madison (N.J.) High.

For all of those men, the game stands out as one of the most memorable moments in their lives. For Taylor, however, the game is an afterthought in one of the most decorated careers in NFL history. Despite a dominant performance, he doesn’t “even think about that that game as far as career accomplishments, [because] the players didn’t belong on the field.” After it was over, several of the replacement players approached LT and asked for his autograph.

“Looking back, it was pretty funny,” Taylor writes. “It’s amongst the strangest games I have ever played in.”

• SUBSCRIBE TO THE MMQB NEWSLETTER: The latest NFL news and the best of The MMQB, delivered to your inbox every weekday morning.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.