Pat Tillman’s Real Legacy: The Soldiers-Turned-Scholars His Foundation Fosters

Marie Tillman doesn’t have much time for the strangers who profess to know what her late first husband stood for. She knew Pat Tillman as well as anyone, so she understands that he never considered his legacy, never called himself a patriot, never wanted to become a symbol. “We talked about our future and all the things we wanted to do together,” she says. “Not, like, what happens if somebody dies.”

She chooses her words carefully from a couch on the sixth floor of a nondescript office building in downtown Chicago, home of the Pat Tillman Foundation since 2013. She wants to make sure she gets this right, because so many others get it wrong. Pat’s legacy is not the story the U.S. military sold after his death, not the glorified image painted in the NFL’s Salute to Service campaign, not the retweet from President Donald Trump this fall that put Tillman on the opposite side of the Colin Kaepernick debate.

Pat was 25 when he left the NFL to become an Army Ranger and 27 when he was killed by friendly fire in Afghanistan. He was a hero. He was also complex, and so were his beliefs. To cast him as some sort of fervent loyalist to the war machine is to mischaracterize the life he lived. Marie describes his thinking as informed, dynamic, evolving. He loved his country and felt the need to question it. He volunteered to fight in a war his journals showed he didn’t believe in. He planned to meet with the anti-war philosopher Noam Chomsky after his deployment ended.

Let others speculate about what Pat would make of the divided America of 2017. They can claim that Pat would have condemned athletes who kneel for the national anthem as unpatriotic, or that he would have knelt alongside them. “I would never want to speak for him,” Marie says. Her work does that.

When Pat was killed, Marie and the Tillman family received thousands of small donations, from $5 bills to $100 checks. Eventually, the total surpassed $1 million, so they started the foundation.

Early on, Marie met two veterans who had returned to Arizona State, Pat’s alma mater, with grand ambitions and little support. She wanted to help them. So in 2008 she sharpened the foundation’s focus, concentrating on aid to soldiers or their spouses as they transition out of combat and onto college campuses. They’re known as Tillman Scholars—520 of them so far—and they’ve received $15 million in support to date. They didn’t lose hope. They embody it.

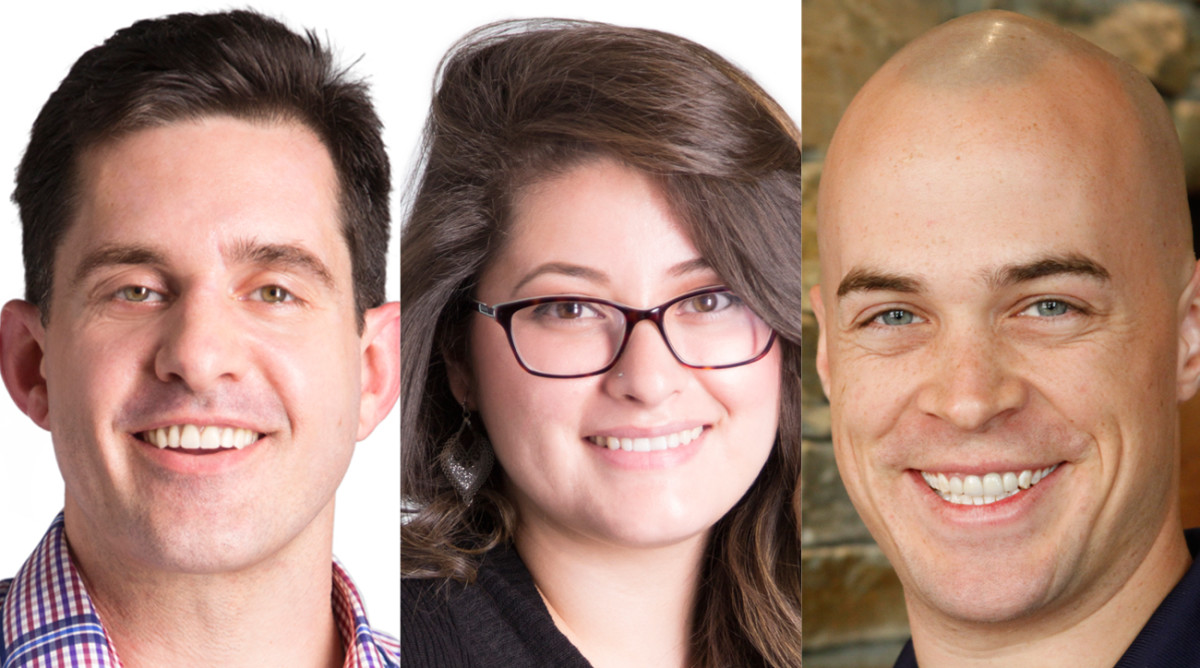

Tillman Scholars become lawyers, business tycoons, engineers, screenwriters, social workers. Like Tillman, Karl Holt joined the military after 9/11, becoming a special forces medic. He was involved in a helicopter crash in Afghanistan in 2009 and, with a broken back, treated 10 wounded before help arrived. Holt underwent 32 surgeries, then enrolled at North Carolina to become a trauma surgeon. Another scholar, Jonny Kim, earned silver and bronze stars for valor in Iraq. As a Tillman Scholar, he received an M.D. from Harvard, and this year he was accepted as a NASA astronaut candidate. He hopes to take part in a mission to the Moon or Mars. Tillman Scholar Laura Moye is the daughter of Mexican immigrants and the wife of a Marine. She studies neuroscience, specifically traumatic brain injuries. Her research could help both football players and soldiers.

Another scholar, Harold Penson, followed a path similar to the life Pat Tillman lived. After graduating from Stanford and finishing his collegiate wrestling career, Penson quit a finance job in San Francisco, enlisted in the Army and became a Green Beret. “I didn’t feel like I could live my life knowing that other people were putting their lives on the line and I wasn’t,” he says.

Penson served four combat tours in Afghanistan, grew disenchanted with military bureaucracy and decided to pursue an MBA at the University of Chicago. He wants to establish a venture capital fund and invest in emerging markets in underserved areas like West Africa. He’s busy, which is good, because he’s trying to avoid Facebook. Too many arguments about kneeling football players. “I personally don’t have a problem with players taking a knee,” he says. “I have more of a problem with veterans prescribing how people should exercise their rights in America. If you’re a veteran and you say people should respect the flag because it’s a symbol of what you fought for, I’d question what that freedom is really worth.”

Sounds like Pat.

“The more time I spend with the scholars, the more optimistic I am about the future of our country,” Marie says.

That’s not so easy in 2017, with police shootings and mass shootings and nuclear threats and wars that continue without end. So Marie continues to speak out, writing Facebook posts opposing President Trump’s travel ban proposal, penning op-eds for The Atlantic—the ban, she wrote, didn’t “reflect the values Pat died for”—and countering the Trump retweet in a statement to CNN. She stands by that statement as she talks in the foundation’s office. Pat’s legacy, she says, should never be politicized, or used to divide.

She’d rather steer all conversations toward the scholars. Always toward the scholars—like Adrian Kinsella, a Marine who befriended his translator named Mohammad while serving in Afghanistan. Kinsella won the scholarship, finished law school and fought to bring the translator to the U.S., away from the dangers of the Taliban. The foundation penned letters to Congress on Mohammad’s behalf, and he moved to America in 2014.

That’s who Pat Tillman was, someone who stood for those who could not stand for themselves.

Marie wrote a book, fell in love again, married again and started a business in Chicago, Mac & Mia, a clothing delivery service for children. She has five kids, including three stepchildren. Sometimes she wonders if she had taken on too much. Then she thinks of Pat. “He would have said, ‘Why not?’ ” she says. “That’s how he plays into my life on a day-to-day basis. His impact. He’s very much a part of who I am.”

Over the years, so many groups wanted to sculpt images in Pat’s likeness or name streets after him or dedicate buildings in his memory that Marie had to create a spreadsheet to weigh the dozens of requests. She chose carefully, deliberately. There’s a stone marker and the Pat Tillman Stadium at his high school in their hometown of San Jose, Calif.; the Tillman Tunnel that players run through at Arizona State, along with a statue; and another statue outside the home of Pat’s NFL team, the Arizona Cardinals. Those are tributes to Pat’s life. They aren’t his legacy.

“There was a point in time where people said to me, You have to move on, you can’t be that involved with the foundation,” Marie says. “But the work we do here, it’s important. It’s not like a statue. That’s his legacy.”

Introducing SPORTS ILLUSTRATED TV, your new home for classic sports movies, award-winning documentaries, original sports programming and features. Start your seven-day free trial of SI TV now on Amazon Channels.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.