Ex-Player Jim Kovach Helps Search for Medical Answers to Football’s Concussion Problem

The more science teaches us about head injury, the more football seems to be doomed. But could science also save football? Might medicine offer us a miracle cure for degenerative brain disease?

Since 2008, pathologists at Boston University have been repeatedly raising the alarm about the effects of life between the lines, finding ever-greater numbers of cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), suspected to be a consequence of repeated head injury, in the brains of deceased NFL players. The current count is 110 out of 111. While the number of diagnosed concussions in pro football was down last season (from 275 to 244), it was still higher than the average over the past five years (243). Unsure of whether the game is worth the risk, several players have walked away from football in spite of promising careers—49ers linebacker Chris Borland in ’15, Bills offensive lineman A.J. Tarpley in ’16, Ravens offensive lineman John Urshel in ’17.

Rule changes and equipment innovations can’t alter the contradiction between physics and biology. The average weight of recruits posting a 40-yard dash at the NFL combine is up by 16.8 pounds since 1987, while the average time is a shade faster by 0.05 seconds. The result is that the average momentum of those players is up by 8.4%, in barely more than a generation. Evolution doesn’t move that fast. The extra collision energy goes into further rattling our bodies and brains. We are not designed to take these hits.

“With just the amount of physics that I learned to get into medical school and the knowledge of the forces within the brain,” says Jim Kovach, a medical doctor, lawyer, entrepreneur, and former player, “my personal opinion is that it would be impossible to truly mitigate the coup-contrecoup—the shaking of the brain, the physical contusion of the brain and the cerebrospinal fluid that is caused by head impacts.”

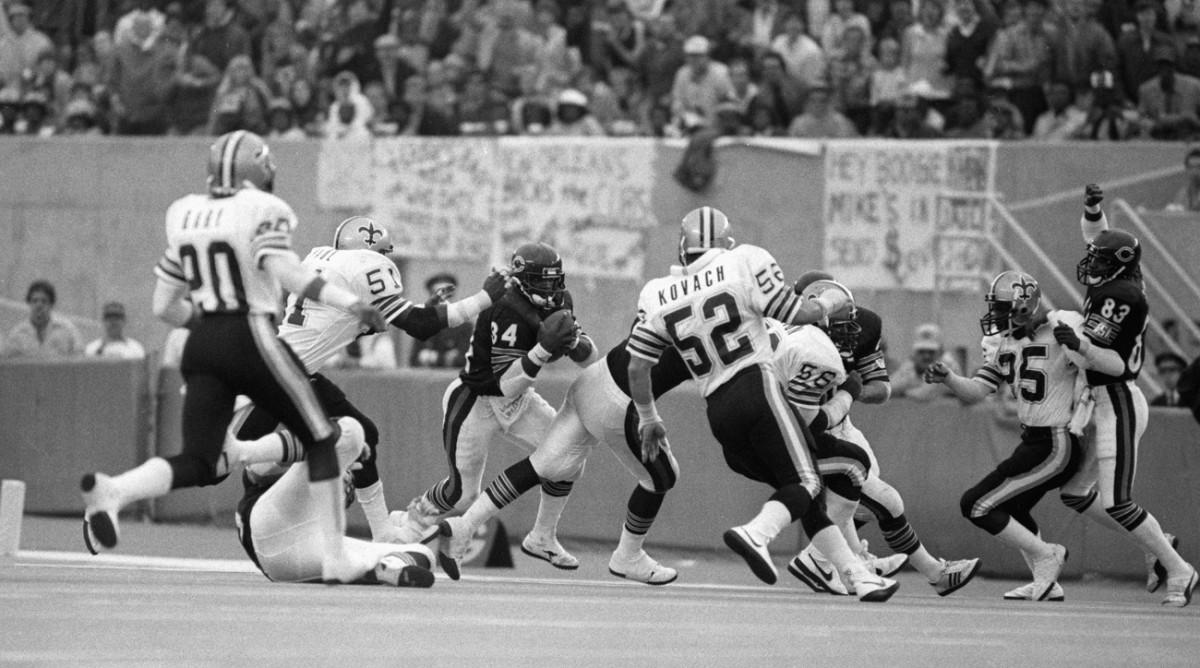

While Kovach doubts concussions can be eradicated from football, the seven-year veteran of the league is hoping the long-term consequences of head impacts can be averted. “I was a relatively undersized middle linebacker who could diagnose plays really well,” he says. “[But] I had a career that was marked by very good form—putting my helmet square in other people’s chests. That’s what linebackers do.”

In August 2016, researchers at a Novato, Calif., based company called Raptor Pharmaceuticals discovered an interesting type of molecule: relatively biologically inert, but transformed into substances similar to existing drugs when exposed to free radicals called reaction oxygen species (ROS). Dubbed captons, these molecules promised to have few unwanted side effects, and to more easily pass through the blood-brain barrier—the semipermeable membrane that separates circulating blood from the extracellular fluid in the brain—than typical neuroprotective drugs.

‘I Feel Lost. I Feel Like a Child’: The Complicated Decline of Nick Buoniconti

Concussions can lead to the creation of higher concentrations of reactive oxygen species in the brain, raising the oxidative stress on neurons. If that stress is too high, the neurons may die and trigger a cascade that affects other nearby cells. Head injury can also lead to the release of too much of a neurotransmitter called glutamate, overloading neurons and disrupting their ability to function normally. This can also lead to neuron death, and neuroprotectants that dampen the over-excitation of the cells can be used to calm the glutamate storm.

The theory behind captons is that they could be taken as a prophylactic before injury. When a concussion causes a spike in ROS, the captons will react with those free radicals and neutralize the oxidative stress. Additionally, the transformed captons will then act as neuroprotectants to de-excite the neurons at the site of injury, and only there. “[Pathology after concussion] is like a ripple effect,” says Sara Isbell, Mercaptor’s CEO and co-founder, “we prevent those ripples from expanding.”

When Raptor was bought out by Horizon Pharma in September 2016, Isbell and other members of the research team founded a new company called Mercaptor Discoveries to develop captons. Kovach, who has served on the NFL Head, Neck and Spine Committee, joined Mercaptor’s advisory board in August.

Kovach’s final year playing college football at Kentucky, 1978, was also his first year in medical school. The Saints drafted him in the fourth round the following June, and he brought his medical textbooks with him. He played through the 1985 season—a year after he gained his MD—then studied law in retirement, graduating from Stanford University in 1990. He then served eight years as the COO for biotech firm Athersys, five years as president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, and is now an innovation and entrepreneurship consultant for the UC Davis School of Medicine.

We Asked NFL Players: What Would You Do If You Found Out You Had CTE?

Kovach credits his academic studies and later work as a reason for why his mind may be healthier than those of other ex-players. A longitudinal study, begun in 1986, on aging and Alzheimer’s disease called the “Nun Study”—the subjects were 678 nuns—has shown connections between learning sophisticated language skills at an early age and a reduced risk of developing AD, and between regular mental exercise and reduced symptoms of AD even when there is underlying brain degeneration.

But Kovach has seen too many of his friends and former colleagues taken down by brain disease to be sure that he will be immune. He played in the 1979 Senior Bowl alongside defensive end Mark Gastineau. Gastineau, a 10-year veteran with the Jets, was diagnosed with dementia and both Alzhemier’s and Parkinson’s diseases last year. Kovach was selected in the same draft as receiver Dwight Clark, and later played with him with the 49ers. Clark announced in March that he has been diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease. Saints coach Dick Nolan picked Kovach in 1979. Nolan died after battling both Alzheimer’s and prostate cancer in 2007. Kovach is sure there are others who may not have a diagnosis, or may not have decided to go public.

Captons aren’t the only potential medical treatments that might offer some sort of cure against the triggering or progression of CTE. Other possibilities include antibodies that might direct the immune system to destroy types of protein molecules that accumulate during the disease, or gene editing to replace genetic variants that appear to raise the risk of developing CTE.

Brett Favre, Concussion Victim, Is Backing Research into a Concussion Drug

Mercaptor is currently studying captons in animal models. Isbell predicts that by mid 2019, the company could start initial human trials to test for adverse reactions in healthy patients, and that within five years there could be clinical trials for patients with, or at risk of, developing neurodegenerative diseases.

If the research holds up, and if it leads to the development of new neuroprotective drugs, Kovach says he’ll be a willing patient. “I’ll raise my hand and say ‘Yes, me too,’” he says. “It’s naïve to think that there’s no chance that I could get [CTE]. It’s tragic to believe that you will, but you can’t believe that you won’t, either.”

• We have a newsletter, and you can subscribe, and it’s free. Get “The Morning Huddle” delivered to your inbox first thing each weekday, by going here and checking The MMQB newsletter box. Start your day with the best of the NFL, from The MMQB.

• Question or comment? Story idea? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.