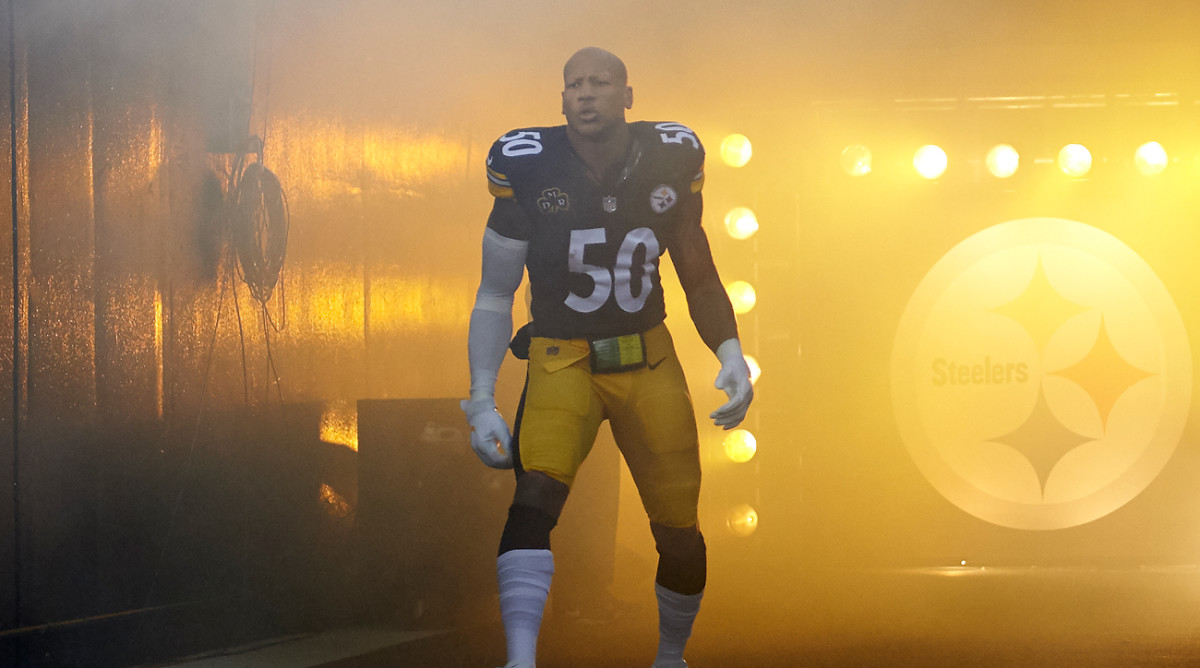

‘It’s All About No. 50’: The Steelers Defense Rallies for Ryan Shazier

The week before the injury that changed everything, Mike Mitchell leaned against a wall outside the locker room at the Steelers’ practice facility. This was early December. His team was 9–2, and Pittsburgh’s resident free safety–free spirit had a lot on his mind.

Like: His closest friend, Ryan Shazier, should be recognized as “the best middle linebacker in football.” And: The Steelers’ defense should be taken more seriously. “Keep focusing on the offense,” he said. “We’re going to keep holding you to 14 points.” And then this: “I’m just gonna say it. We’re gonna win the Super Bowl.”

His defensive teammates concurred. All anyone noticed was the Steelers’ star-studded offense—Ben Roethlisberger, Antonio Brown, Le’Veon Bell. . . . But, they pointed out, the front office had transformed their unit since 2014, when Pittsburgh used the 15th pick on Shazier, now the most beloved player on the team. Everything they did—and everything they would do—revolved around him.

Another point of agreement: Because they had found a defensive anchor in Shazier (and more balance overall), they were better positioned to topple the Patriots in the AFC and add a seventh Lombardi Trophy to their already crowded case. In each of the past three seasons they had advanced one round deeper into the playoffs, losing to New England 36–17 last January in the conference championship game. And in each of the past four offseasons they reinforced their defense, drafting seven starters in the first three rounds.

When Mitchell addressed his nephew’s high school basketball team last March, he told them, “I still don’t sleep well, thinking about Tom Brady.” And, back in the hallway, he said that hadn’t changed. “I’d be lying now if I said otherwise,” he said. “Look, the Patriots are the benchmark. That’s the team we’re going to have to knock off if we want to win the Super Bowl.”

Three days before the Steelers played at Cincinnati on Monday Night Football in Week 13, Shazier walked into an otherwise empty defensive meeting room at 8:30 a.m. He settled into a leather chair in the front row, unleashed a waterfall of syrup upon a pile of French toast, cracked a lime sports drink and cued up film of a Week 7 game against the Bengals on a 20-foot-tall projection screen. Digging into his breakfast, he used his free hand to hit pause. “There,” he said, aiming a red laser pointer at running back Joe Mixon, jump-cutting from Shazier’s grasp. That’s how Mixon gets free—but this time Shazier would be ready.

This time. Those words would mean one thing on this random Friday morning, and something far more haunting three days later.

The film ran as Shazier finished his syrup soup. A reporter pointed out that 31 of 51 Super Bowls have been won by teams with top-five scoring defenses, and that the last time a No. 1 scoring offense prevailed was way back in 2009. (On this day Shazier’s D ranked fourth in scoring with 17.5 points per game; the offense, struggling, was 10th, at 22.6.) “Defense matters,” Shazier said. “And we haven’t even played truly great football yet. Like, I dropped three picks already this year.”

Teammates trickled into the meeting room and settled into the back row, away from Shazier, who lobbed playful insults their way as they played a heated game of War. The linebacker lamented tackles missed and big plays surrendered, but this, he said, was the closest team he had ever played on. These guys would overcome anything.

Shazier, 25, was so young and optimistic and self-assured, thisclose to the ring he has coveted. “This year just feels different,” he said.

Everything changed in the first quarter on Dec. 4. Shazier was attempting a routine tackle on Cincy wideout Josh Malone when he slammed into Malone’s thigh, largely with his right shoulder, and fell to the ground, clutching at his back. He didn’t move his legs, and his teammates’ faces filled with the kind of dread rarely seen on an NFL field. Mitchell, in street clothes nursing an ankle injury, ran to his side. “Bro! Yo, what’s up?” he yelled. “You all right?”

Tears streamed down Shazier’s cheeks as he kept repeating, “I can’t feel my legs.” Mitchell had witnessed teammates break ankles, shred ACLs, wobble after concussive hits—but never anything like this. In the aftermath, inside linebacker Vince Williams (who also calls Shazier his best friend) took over the play calls. “I don’t think Vince stopped crying until after halftime,” Mitchell would later say—“and that’s one of the most gangster dudes on the team. People had to grab him by the face mask and be like, ‘Yo, you’re the middle linebacker now. You can’t be sniffling.’ ”

Shazier went straight to the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and was transferred two days later to a Pittsburgh facility, where he underwent spinal stabilization surgery. Details of his condition remain closely guarded, per his wishes. Several Steelers told SI last month they simply hoped Shazier would walk again. Last week came word, through WPXI Pittsburgh, that Shazier was slowly regaining feeling in his legs, but it’s too early to say anything about his long-term future.

In December, Mitchell visited Shazier in the hospital weekly. The two men reminisced about the virtual college football dynasties they’d built on PlayStation, and they laughed about the first time they met, Shazier asking Mitchell to mentor him and starting that conversation: “I want to be a Hall of Famer.”

“I was watching that guy barely be able to sit up in a bed,” Mitchell says. “He’s got RJ, his little boy, and I want him to be able to run and play with him.”

Of far less importance, Shazier’s injury has extensive implications for the Steelers. Their goals—beat the Patriots, win Super Bowl LII—remain unchanged, and their defense still revolves around a passionate 25-year-old inside linebacker. Just not in the same way. Shazier’s injury divided Pittsburgh’s season into two parts: what they did with him, and what they’ll do for him.

“I believe we’re going to win it now even more,” Mitchell says.

As Shazier lay on the turf, defensive end Cam Heyward didn’t know what to do. “Get up, get up, get up,” he said, gripping Shazier’s left hand tightly, trying to calm him. The rest of the game unfolded in a haze, with Heyward trying to rally shaken teammates. “We have to win for Ryan,” he told them. “Ryan’s going to be O.K.,” he said, not knowing if that was actually true.

In the weeks that followed, Shazier’s defensive teammates wrestled with his injury and what he meant to them. Heyward, a first-round pick in 2011, had watched the defense’s makeup start to change in ’14, when he welcomed Shazier, a fellow Ohio State product. A team defined by its best defensive players had won Super Bowls after the ’05 and ’08 seasons (and then lost one after the ’10 campaign), but by Shazier’s second season almost all of those players had retired. The subsequent Steelers teams came to be known for their offensive firepower, but “when we [drafted] Ryan,” Heyward says, “it felt like a turn back the other way, the start of a new nucleus.”

Along with Shazier, Pittsburgh added Notre Dame defensive end Stephon Tuitt in the second round in 2014, then Kentucky outside linebacker Bud Dupree in the first round of ’15. Heyward, meanwhile, inked a six-year extension worth almost $60 million, and while the juggernaut offense hogged headlines, the two Buckeyes worked in devastating tandem: Heyward cleared space in the interior for Shazier to make tackles, and Shazier blanketed short routes, allowing Heyward time to chase QBs.

Heyward tore his left pectoral muscle in Week 10 last season (he played the rest of that game with one usable arm, then sat out the remainder of the season), but by then the young core was starting to take hold. Rookie defensive backs Artie Burns (Miami) and Sean Davis (Maryland), thrown into the fold immediately, were growing confident. Shazier remained a force. The unit’s improvement—No. 4 in yards allowed over the last seven games of 2016—alternately depressed and motivated Heyward, who poured over so much of his old film, holed up, lights dimmed, that “I looked like Tom Hanks in Cast Away,” he says. Later, “watching them make that playoff run, watching them lose [to New England], it ate me up inside.”

He came back stronger this season, with 12 sacks (tied for eighth in the NFL), but Heyward’s most important work has been behind the scenes, rallying the Steelers around his old running mate.

“I don’t care about the Pro Bowl,” he says, referring to Pittsburgh’s disrespectful dearth of defensive representation. (Shazier was voted in, no one else; Heyward was named All-Pro last week, the only Steelers defender on the list.) “I care about Ryan and his health.”

Before his first news conference as a professional, in April 2016, Artie Burns stopped at the Franco Harris statue on his way to baggage claim at the Pittsburgh airport. “I didn’t know who [Harris] was, but then they told me about the catch,” says the 22-year-old corner, referring to Harris’s Immaculate Reception in 1972. Burns posed for a photo next to the likeness, then rode to team headquarters, past all the Steelers signage, and stopped to ogle the Super Bowl trophies behind the glass on the second floor. Later that day Shazier introduced himself. “You’ll come to understand the history here,” he said.

Even as he learned, Burns found himself lonely. His mother had died of a heart attack six months earlier; his father was in prison on a 25-year cocaine-trafficking conviction. Artie vowed to take care of his two teenage brothers, 16-year-old Thomas and 13-year-old Jordan, but he had to leave them with relatives back in the Liberty City section of Miami, settling for FaceTime check-ins every night.

After Tom Brady accelerated the young corner’s education with 384 passing yards and three TDs in that AFC title game rout last January, Burns went home, took his brothers bowling and to the county fair, and returned with them to Pittsburgh, where he looked often to a certain inside linebacker for advice. He got engaged, started every game and was reestablishing the integrity of the Steelers’ secondary when Shazier was injured.

Burns has since had trouble sleeping. He prays for his teammate, thanks God for Thomas’s track scholarship to Miami and questions whether he even wants Jordan—a linebacker, like Shazier—to play football. Rallying around Shazier has been easy. Reconciling what happened to him has been infinitely more complex.

“The lick was loud. I heard it, like, BOW!” says Vince Williams, who came over Shazier’s back to finish the tackle that changed everything.

Williams turned around to celebrate—until he saw the panic in his friend’s face. “That f----- me up,” he says. “I’m watching the trainers pinch him. They’re not really telling him they’re pinching him, and they’re just pinching the s--- out of him.”

The two linebackers had enjoyed a football bromance all offseason, working out together and laying out their goals. Shazier planned to lead the team in interceptions, and Williams would pace Pittsburgh in sacks—Shazier insisted his friend was capable of replacing Lawrence Timmons, the latest stalwart to depart. They had both seen it before, the team’s organic approach to football operations: Heyward replacing Brett Keisel, Mitchell replacing Troy Polamalu. . . .

The idea of Williams as an essential cog in the league’s most improved defense would have seemed a stretch back in 2013, when Williams received a last-minute invitation to the Senior Bowl—only after Manti Te’o had dropped out. (Just one scout, with the Steelers, deigned to speak with Williams in that game’s lead-up, but his first question—“What’s Bjoern Werner like?”—gave away his intentions.) The Steelers drafted Williams mostly because coach Mike Tomlin had an affinity for Florida State linebackers—and if they cut him, Williams had a backup plan in mind already: He would become a high school principal.

But then the two friends were doing it, the 2017 season unfolding exactly as they had planned. Shazier took the team lead with three interceptions in the first nine games; Williams racked up five of his eight sacks. Everything went so well, in fact, that Williams, a creative writing major at Tallahassee who counts David Sedaris as his favorite author, had stopped composing. “I’m too happy to write,” he said before Shazier’s injury. “A lot of my writing came out of life experiences. I’m a cake eater now. My life is great: I start for the Steelers, I get sacks, and I’m a millionaire. Nobody wants to read that s---.”

In the week before Shazier’s injury, Williams told his defensive teammates they weren’t the “little brothers [to the offense] no more.” They’d matured beyond that; O and D were equals. Two days after the injury, he spied Shazier’s number 50 practice jersey and tugged it on. He thought about winning a Super Bowl without his linebacking partner and decided “that would suck.” But it beat the alternative. Not winning anything for Shazier would be worse.

Over the course of seven miserable seasons with the exceptionally execrable Browns, cornerback Joe Haden had, in his words, “two owners, a couple general managers, about five different head coaches, too many position coaches to count and 45 quarterbacks.” (He’s not that far off.) The only constant: change. And he knew one day he might be the one heading out.

That day came last August, when Sashi Brown, the GM then, told Haden he was no longer a top-five NFL corner and would have to take a pay cut. Haden asked for his exit and got released. (Haden: “They were going to pay Brock Osweiler $16 million and he’s not even on the team [after being signed and cut this summer], and they wanted to cut money from me!”)

The Steelers were first to reach out to the free agent, and the interest was mutual. Haden had connected with Tomlin at the 2010 NFL combine, and his college teammates from Florida (tackle Marcus Gilbert and center Maurkice Pouncey) raved about Pittsburgh’s locker room. Haden says he turned down higher offers from three teams to sign a three-year, $27 million contract with only $5.8 million guaranteed at signing.

“They’re dumb—that’s Cleveland,” says Mitchell. “You can’t find a top-10 corner in September; that just doesn’t happen. He was the final piece.” But Haden did more than just top off the Steelers’ defensive transformation. He changed the way coordinator Keith Butler could scheme against opposing offenses, including the one they most needed to stop. Specifically, Haden’s arrival allowed Davis to move full-time to strong safety, where he’s become a starter; it freed Coty Sensabaugh, a rare free-agent signee (from the Giants) to shift into the nickel corner role; and it meant that 33-year-old William Gay (a remnant of Pittsburgh’s last Super Bowl team) could play exclusively in dime packages. In essence, by adding Haden and sliding players down they improved at nickel, dime and down the line through the reserves. And that depth gave Butler the flexibility to add designer blitzes (astonishingly, corner Mike Hilton had three sacks in one game, against the Texans) and hybrid coverages.

If he even needed them. Butler has actually blitzed less frequently—this is Blitzburgh no more—relying on interior pressure from Heyward and Tuitt, along with this season’s first-round selection, outside linebacker T.J. Watt. Fewer blitzes mean that “Coach Butts,” as his players affectionately call him, can drop more defenders into coverage—and that’s a blueprint for beating Brady.

The result: Aided by an improved secondary that has forced passers deeper into their progressions, the Steelers racked up a franchise-record 56 sacks (from 15 different players), the NFL’s highest total since 2013. There were blips—see: Bears, Bengals, Browns and an A-Rod-less Packers—but they often outplayed their own vaunted offense. Despite Shazier’s injury (and others, including to Antonio Brown), Pittsburgh finished 13–3, securing a first-round playoff bye, and hosts the Jaguars this Sunday.

Even Haden—the newcomer who felt the unfamiliar sensation of playing for a winning team—knows how to frame this postseason. “It’s all about number 50,” he says.

A month after that Bengals game, Shazier’s locker appears untouched. A black helmet, newly polished, hangs from a hook above Prada shower sandals and a rack of black sweatshirts and gold hats, everything arranged neatly, ready for his return.

Shazier has approached rehab the way he approaches everything in football: with more concern for his teammates than for himself. He has remained active on a group text thread that gives a handful of players their defensive game plan early. He asked his doctors to move his Friday physical therapy sessions so that he can wheelchair into his team’s so-called Winning Edge meetings, where Tomlin gathers his linebackers and defensive backs to go over opponents’ tendencies and schematic wrinkles. In one conference, in late December, Shazier chided his coach about a new package, “Seven,” that called for seven DBs and zero linebackers. “This is getting insane!” Shazier joked.

Teammates won’t speak to the specifics of Shazier’s progress, but they will say that he has progressed faster than they expected. One week after his injury, when the Steelers sealed a third AFC North title in four years by beating the Ravens, Tomlin presented him the game ball over FaceTime. The next week Shazier attended a home game against the Patriots, watching from a suite, seated and waving a yellow Terrible Towel on the jumbotron as chills ran through Burns’s body, goose bumps dotted Heyward’s arms and tears welled in Mitchell’s eyes.

Later, in the same defensive meeting room where Shazier drenched his French toast, someone pointed out the quiet. “That’s ’cause Sha and Mike aren’t arguing,” chimed in a scout.

Damn, Mitchell thought, overwhelmed by sadness. “Literally all we did was argue,” he says, “and I miss that. But then I think about my boy, and how he gave up his ability to move just for us to win a game. If he’s willing to make that sacrifice, I’m willing to do anything—anything—for us to win for him.

“We’re going to play [the Patriots] again,” Mitchell promises. “We can play them in hell, we can play them in Haiti, we can play them in New England. . . . We’re gonna win.”

He lays out his dream scenario: The Steelers reach the Super Bowl, Shazier makes an appearance, and Pittsburgh triumphs. “It’s destiny,” he says. “I’m praying every day that he won’t be in a [wheelchair], that he’ll be on the sideline and run up and celebrate it with us. There’s gonna be hella people crying when it happens.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.