Advantages and Drawbacks of the XFL Operating as a Single-Entity Sports League

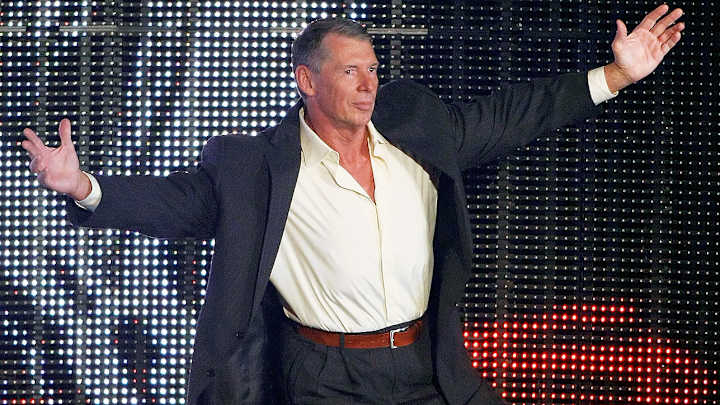

Like its first incarnation 17 years ago, the new XFL is set to strike a very different tone than the NFL. In a press conference on Thursday, WWE chairman and CEO Vince McMahon offered details about his new league, which is scheduled to begin play in 2020 with eight teams. Among those details are ways the XFL is distinguishable from the NFL particularly in areas where the NFL has attracted controversy. For instance, McMahon signaled that players with criminal records would not be eligible. He also suggested that players would be required to stand for the national anthem.

These and other variations will be made more possible by the business structure of the XFL and the legal advantages it offers. The new XFL will, like the former XFL, operate as a so-called “single-entity sports league.” A single-entity sports league refers to one where the league owns all of the teams and controls all aspects of operations. This means the league employs the players, coaches, trainers and other staff. It also means the league oversees all aspects of team activities, including marketing, promotion, broadcast and intellectual property. Alpha Entertainment—a company Vince McMahon founded—will own the XFL.

Why the XFL has chosen the single-entity model

There are many advantages for the XFL in operating as a single entity. First, a centralized structure allows the XFL to function in an efficient and controlling manner. The league can design policies with the entire XFL’s interests in mind and can then implement those policies unilaterally. There will be no XFL team owners who might object to the XFL for self-interested or factional reasons. If the XFL endorses a certain organizational culture, XFL teams will have no choice but to follow it.

Second, there will be operational cost savings for the XFL. Business, marketing and legal positions in the XFL headquarters could largely run individual teams’ operations. In contrast, NFL teams employ fairly extensive staffs for their operations.

Third, a single-entity league like the XFL is more transferable than a league of 32 different ownership groups. Think of it this way: If the XFL and its eight teams succeed as a business, McMahon could sell them all as one asset. In contrast, it would be extremely difficult to convince 32 separate NFL owners to agree to “sell the NFL.”

Fourth, there is a significant legal benefit in operating as a single entity—the XFL will not be subject to Section 1 of the Sherman Act. Under Section 1, competing businesses are forbidden from conspiring or colluding in ways that unreasonably harm competition. The major four pro leagues have each been challenged, with varying levels of success, on Section 1 grounds. Leagues are vulnerable to Section 1 claims because those leagues feature individually owned teams that are competing businesses. Section 1 lawsuits are threatening in that if they are successful, they lead to treble (triple) damages.

Take the NFL and Section 1. If the New York Jets and the 31 other teams joined hands to unilaterally limit the amount of money an NFL player can earn, such a limit would be subject to a Section 1 claim. The same would be true if the Carolina Panthers and the 31 other teams decided, without player approval, to forbid multi-year player contracts. The Jets, the Panthers and the 30 other NFL teams are competing businesses. Anti-competitive restrictions on wages and other working conditions are classic grounds for antitrust challenges.

So why don’t we see players suing over the NFL salary cap and similar limits on their pay? It’s because those rules have been collectively bargained with the National Football League Players Association. Generally, rules that primarily impact employees’ wages, hours and other working conditions are exempt from Section 1 claims if they have been collectively bargained with a union.

Now back to the XFL. This entire discussion on Section 1 is irrelevant to the XFL for a very simple reason: There are no competing businesses in the XFL. Alpha Entertainment will own the eight XFL teams, just like Alpha Entertainment will own the XFL itself.

The U.S. Supreme Court is clear that a parent and its wholly owned subsidiaries are incapable of conspiring with each other for purposes of Section 1. This is good news for the XFL and its eight teams. At the same time, the Supreme Court has rejected extending single-entity recognition to other kinds of sports leagues. In 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 9-0 decision, held that the NFL is not a single entity for business purposes because NFL teams are individually owned and to some degree autonomous.

Without needing to worry about Section 1, the XFL could unilaterally impose aggressive wage restrictions, strict drug-testing procedures and other workplace requirements that would surely attract opposition from the NFLPA if the NFL tried the same. If XFL players don’t like those rules, they could seek professional football opportunities elsewhere. This structure was exactly what sports attorney Alan Rothenberg had in mind when he designed MLS as a single entity. He wanted the league to avoid Section 1 lawsuits.

That’s not to say a single entity prevents XFL players from having a voice. For instance, they could unionize and seek to negotiate a CBA with the XFL. But unionization is hardly an instantaneous process and it is far from a slam dunk to occur with XFL players. XFL players didn’t unionize in 2001. And UFC fighters—some of whom have used a different area of antitrust law to sue the UFC over its wage structure—have not unionized while competing in a single-entity sports league that’s been around for 25 years.

What Is Vince McMahon Really Saying With the Rules of His “Rebooted XFL”?

Drawbacks to single-entity status for the XFL

While there are many advantages for the XFL in organizing as a single entity, there are also some potential drawbacks.

One might be fan concern that, like WWE fights, XFL games could have elements of choreography. The league owns all of the teams and employs everyone who works for those teams. With such power, the league could dictate play calling to stimulate interest in a particular game. Or the league might demand that certain players play in a particular game whereas others sit. The XFL will need to be transparent about its operations as it relates to competition and fair play. If it isn’t and if it markets a product in a deceptive way, it could run afoul of consumer protection laws and Federal Trade Commission regulations.

Second, fans might not like the idea of teams without owners. While some NFL owners are relatively quiet or even boring, others clearly aren’t. Part of what makes the Cowboys compelling is Jerry Jones, who obviously is as passionate about the Cowboys as any of the team’s fans. The same could be said of Robert Kraft, who was a Patriots season-ticket holder for 23 years before he bought the team in 1994. Many other teams have similar stories of the owner as a diehard fan. There is no denying their love of their teams and their fans appreciate it. XFL teams won’t have that.

Reimaging the NFL as a single entity and analyzing two major single-entity sports leagues: MLS and UFC

Think of how differently the NFL would operate as a single entity. Roger Goodell wouldn’t work for team owners because there wouldn’t be any team owners. He would instead work for the person, people or company that owned the NFL. Jerry Jones and Shahid Khan wouldn’t own the Cowboys and the Jacksonville Jaguars, respectively, because the company owning the NFL would own those teams. The closest Jones and Khan could get to NFL ownership would be through buying equity in the company that owned the NFL.

Also, NFL headquarters, rather than team general managers, would likely design player trades. Trades, then, could be devised without the goal of advantaging one team. Instead, trades would aim to evenly distribute player talent across all of the teams. That way, the overall NFL product would be more competitive. As a result, dynasty franchises like the Patriots might not exist and Tom Brady might not be able to play his entire career in New England.

Speaking of the Patriots, Deflategate and other controversies that raise questions about the league’s credibility while investigating teams and players might never come to light. The players and team officials would all work for the same company—the NFL. And the NFL would assign discipline as it sees fit. In a single-entity NFL, it could more easily keep brand-damaging controversies “in house” and out of arbitration rooms and courthouses.

This alternative universe obviously doesn’t exist, but there is a major pro league in the U.S. that for many years operated in this manner. Major League Soccer (MLS) was founded in 1994 as a single entity. That is, MLS owned all of the teams, which functioned more like departments in a single company than rival businesses. MLS itself was owned by a group of investors, including Kraft and the late Kansas City Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt.

The original design of the MLS wasn’t a pure single-entity sports league, but it came awfully close. MLS negotiated all broadcasting deals, enforced intellectual-property rights and—most noticeably to fans—assigned players to MLS clubs. Individual teams retained a limited degree of autonomy through “operators-investors,” who could adjust player salaries depending on the team’s success. But the league called the shots.

However, as the years have gone by, MLS has moved away from the single-entity model. It has done so as it has grown in popularity and elevated its quality of play. This change is particularly true in regards to the “Designated Player Rule” (sometimes called the “David Beckham Rule”). The rule allowed the Los Angeles Galaxy in 2007 to sign soccer star David Beckham, who otherwise wouldn’t have signed with an MLS team due to the MLS-imposed salary cap. The league permitted the Galaxy to not only exceed the salary cap, but also to pay most of Beckham’s high salary (as opposed to MLS paying it). Other teams have since relied on the Designated Player Rule to sign international stars who would otherwise probably play in more prestigious leagues elsewhere. MLS teams have also become more autonomous in regards to stadium deals and marketing. Taken together, MLS teams have steadily become more like independent businesses and less like company departments.

Another major single-entity sports league is the Ultimate Fighting Championship. The UFC is owned by William Morris Endeavor Entertainment, which also owns Professional Bull Riders. The UFC is, of course, very different from a pro football league or a pro soccer league. It involves individual fights rather than team play. Nonetheless, it is a single entity and clearly a successful one at that—the UFC was sold to William Morris Endeavor in 2016 for approximately $4 billion.

Particularly given the relationship between McMahon and the XFL, it is worth noting another possible single-entity “sports league:” World Wrestling Entertainment. While some would object to describing the WWE as a sports league given that its fights are choreographed, it relies on skilled athletes.

It will be interesting to see the XFL play out. Its design will play an influential role.

Michael McCann is SI’s legal analyst. He is also an attorney and the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, and co-author with Ed O'Bannon of the forthcoming book Court Justice: The Inside Story of My Battle Against the NCAA. As a disclosure, McCann has been an advisor to Your Call Football, a gaming technology startup that will debut later this year and feature live football.