Brandon Graham, an Underdog Since His High School Years in Detroit

The MMQB is on the road to Super Bowl 52. Follow along on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram and find all of our road trip content here.

DETROIT — The only sign that this was once a football field, let alone one that produced a player headed for the Super Bowl, is a solitary goalpost. It’s standing alone in a city park that’s more dirt than grass, covered with goose droppings and discarded tires, just off I-75 about a mile from Ford Field. Even when football was played here, the grass was mostly gone before football season; at the 2-yard line was a block of cement, the leftover base of an old pole, which they’d push some dirt on top of every time they took the field.

This was the old site of Crockett Tech High School, the school itself consisting of a portable trailer. In the afternoons, students would walk across the parking lot to take classes at the adjacent vo-tech center. There were no lights surrounding the dirt field, so football games were usually played at 3:30 p.m.; when practices ran past sunset as the fall days grew shorter, parents would help light the field with the headlights of their cars.

“This produced teachers, lawyers, accountants, a host of college players, NFL players … from a trailer park,” says Tim Hopkins, a former associate head coach and defensive coordinator for Crockett, gesturing out over on the field on a Saturday morning in January. “The little engine that could. That was the backdrop for where Brandon Graham played.”

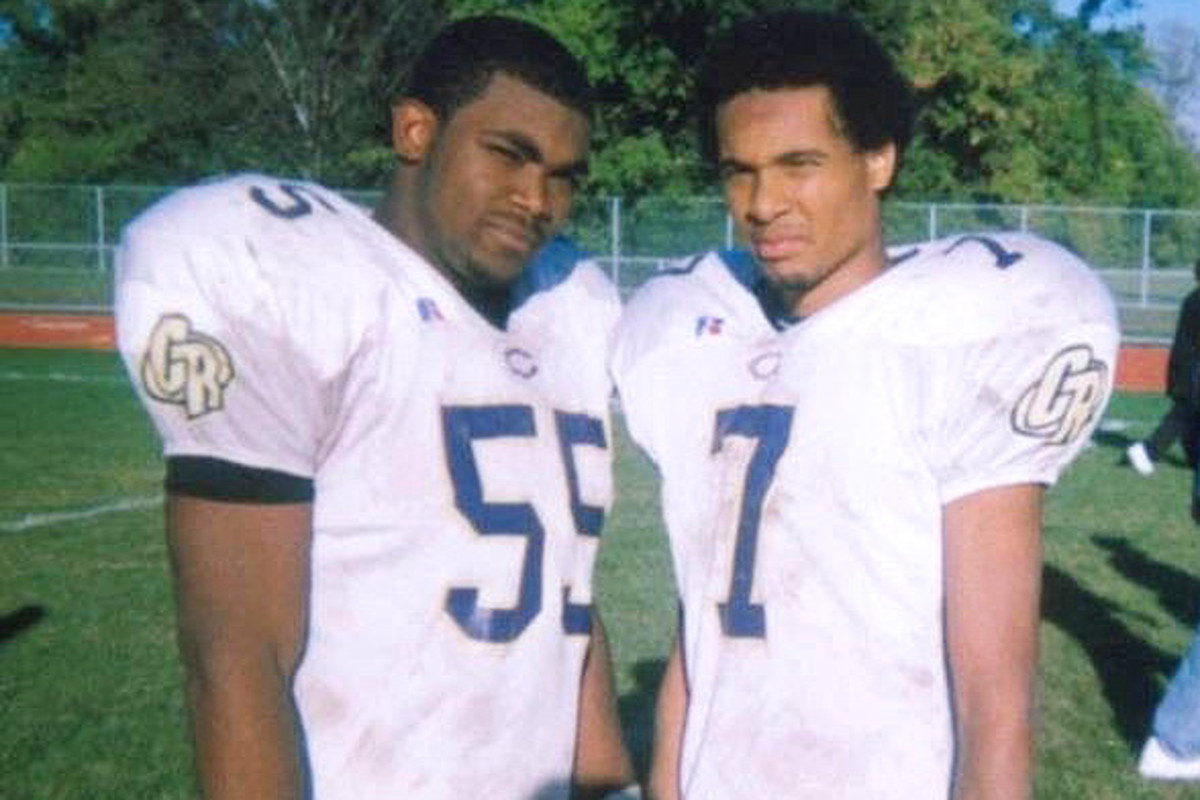

Graham is now a pillar of an Eagles team riding its underdog status to Super Bowl LII, a playmaking defensive end who has lent both his ability (9.5 sacks) and his mentality to a team that hasn’t been favored to win any game this postseason. Years earlier, Graham was the heart of another underdog squad—the Crockett Rockets. Most of his old field is gone now, the space mostly occupied by an indoor cycling track. But enough remains for it to be a time capsule of the years that helped produce one of the most impactful Eagles players.

“Wow,” Graham wrote in reply to a photo of the field posted on The MMQB’s Instagram stories, “that brought back memories right there.”

Crockett had been open less than 10 years when Graham enrolled in 2002; its football program had only been around six years. In Detroit, many ninth-graders choose to still play with their little league teams. But as a freshman, Graham had long since outgrown the level of competition of the Eastside Giants. After his father, Darrick Walton, brought him to meet with the high school coaches, Graham joined Crockett’s varsity squad.

A high school operating out of a trailer certainly didn’t have football facilities. Players changed for practices and games in a hallway located in the basement of the middle school next door. They had a few rows of bleachers around the field, but no way to fence them off, so they couldn’t charge admission for the games.

“Today’s players would never survive what he had to go through just a little over 10 years ago,” says Rod Oden, an assistant who took over as Crockett’s head coach for Graham’s senior season.

The roster was thin, around 25 players, barely enough to run 11-on-11 drills in practice. Everyone played both ways. Graham was a middle linebacker, offensive guard, placekicker and punter. Knowing opponents would be afraid to tackle him, the coaches would wink his direction when they wanted to send him on a fake punt. It’s an impossible stat to verify now, but Hopkins reports that Graham scored on the fakes “about 98% of the time.”

Crockett’s fledgling football program didn’t attract top colleges early on. Hopkins jokes that the recruiters from bigtime programs would get off I-75 to go to the McDonald’s catty-cornered to Crockett, then get back on the interstate and drive off to Cass Tech or King High School, the more established programs nearby with better resources. By the time Graham got there, that was just beginning to change. There was a group of D1 recruits a few years ahead of him; Hopkins recalls the late Joe Paterno sitting in a tiny room in that infamous Crockett trailer pitching a defensive lineman named Ed Johnson to come to Penn State. A few years later, Michigan’s Lloyd Carr came calling for Graham.

Graham blossomed into the top-ranked player in the state his junior season, a 6' 2", 240-pound linebacker who could out-run most of the running backs they faced (he would later be clocked at 4.43 seconds in the 40-yard dash at a Nike summer camp). The Crockett coaches had a policy that each season the players had to earn the “C” they wore on their helmets, by meeting certain performance or effort benchmarks. These were marks Graham would easily meet, but one year, he told his teammates that neither he nor anyone else on defense would wear the emblem until everyone earned it. So for the first couple games of the season, the best high-school player in Michigan played with a blank helmet.

In 2004, Graham led Crockett to an undefeated regular season and the school’s first Detroit Public School League title (they went on to lose to powerhouse Jackson Lumen Christi in the state semifinals). The areas where Crockett lacked, they used as motivation and found ways to compensate. That sounds a lot like Graham’s current team, which has overcome the loss of a starting quarterback, starting left tackle, top linebacker, most versatile running back, core special-teamer, etc., to nonetheless reach the Super Bowl.

“I remember the grind and how we were a tight-knit family because of the numbers we had at Crockett,” Graham wrote over social media. “It taught me to appreciate everything because we didn’t have much, but we maximized what we had to accomplish so much.”

Crockett relocated to an old middle school building for Graham’s senior year, and closed its doors altogether in 2012. That building now stands vacant and overgrown, a visible reminder of Detroit’s struggling public school system. Nearby in the east Detroit neighborhood where Graham grew up, though, is East English Preparatory Academy, which opened after Crockett closed and is where Oden now coaches.

Graham never walked these hallways, but the school is a few blocks from where he used to live, and he makes a point to visit several times a year. He hosts summer sports camps for both boys and girls with his wife, Carlyne, whom he met at Crockett; he’ll sometimes even work out with the football players in their gym where not all the dumbbells have a match. A few years ago, Graham surprised the East English team with new home and away uniforms; last year, he donated 60 helmets from Xenith, a Detroit-based company that has produced several of the top-performing helmets on the market.

“Brandon doesn’t fill up his camps with the kids that are super studs,” Oden says. “He wants the kids who will sign up on their own, get up at 8 a.m. and come here and give a great effort, regardless of skill level.”

Graham didn’t enter the NFL as an underdog, but when the first-round draft pick out of Michigan in 2010 struggled with injuries and scheme changes his first few years in the league, he took on the “bust” label as a personal challenge. He’s flourished the past two seasons as a 4-3 defensive end in Jim Schwartz’s system, but that proverbial chip on his shoulder that he’s carried in different ways his entire career is quite befitting of an Eagles team that cut through the NFC playoffs as a rare home ‘dog.

This weekend, against Tom Brady, Bill Belichick and the heavily favored, five-time champion New England Patriots, Graham's former coaches are expecting to see that old Crockett mindset rear itself in the trenches. Hopkins got choked up while pulling up to that old Crockett field where the players would run so hard the goose droppings would become mulch and they’d go home after practices and games with dirt in their noses.

“New England in Brandon’s mind is like playing King or Cass,” Hopkins says. “There’s so much synergy in the fact that the Eagles are using that underdog mantra to catapult themselves to the Super Bowl. That team is taking on the façade of a Crockett team.”

Graham, who was back in Philadelphia preparing for the team’s charter flight to Minneapolis, agreed with this premise. “That’s exactly right,” he wrote. Graham and the Eagles know that if they win this weekend, they can no longer claim that underdog status; but, they only need it for one more game.