When No One Believed in the Belichick Way

MINNEAPOLIS — Eric Mangini dislikes clichés as much as anybody, but he cannot think of any other way to tell the story of the 2000 Patriots without this one: A rag-tag group with a wild, out-of-the-box idea sets out to change something; after it initially fails, they are abandoned by almost everyone who was once in their corner.

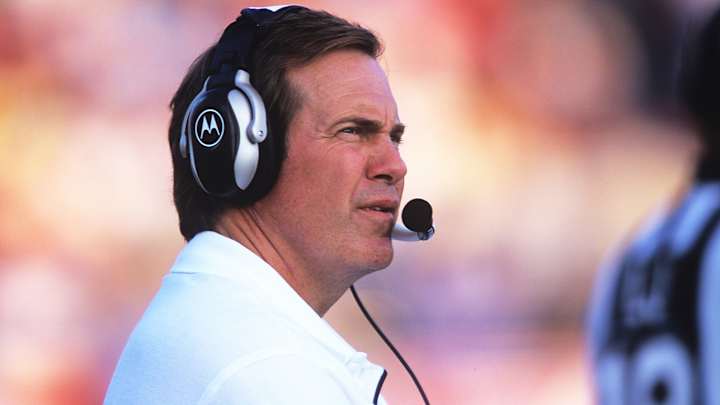

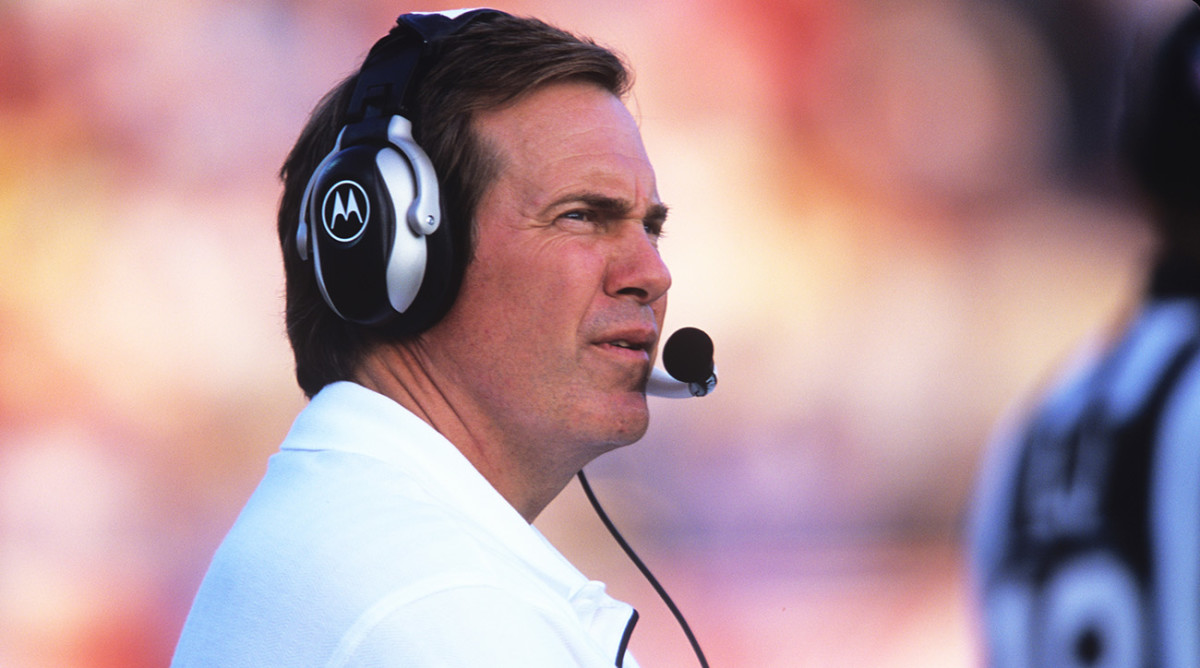

He was specifically referencing the turbulent stretch between January 27, 2000, when Bill Belichick became head coach of the Patriots, and Oct. 7, 2001, when New England was beaten 30-10 in Miami to fall to 1-3. That made Belichick 6-14 over his first 20 games as New England’s head coach.

“It was rough,” Mangini, then the Patriots’ defensive backs coach, says. “We went into New England and it wasn’t well received. People seem to forget how negatively received the whole thing was.

“You had Bill coming off the negative Cleveland experience, the trade [of Belichick from the Jets] and all the things that went into it. Then we go 5-11, start 2001 slow, [Drew] Bledsoe gets hurt, it wasn’t exactly a well of optimism. There was a pretty small group of people who believed in what we were doing.”

The minutia involved in turning around a franchise was exhausting, if only because Belichick kept his blinders on. His belief was steadfast, and that meant leading his coaching staff through a daily steeplechase of rigorous scouting, preparation and planning while they themselves were not sure if they should put their homes on the market. The insanity crescendoed when the staff’s job security was placed in the hands of a gangly sixth-round draft pick from the University of Michigan after Bledsoe went down in the second game of 2001. Belichick was good about keeping any conversations, good or bad, with owner Robert Kraft away from the staff. But would it only be a matter of time before Kraft caved to fan pressure like every other owner in the NFL?

“If we had had another really bad year [in 2001], I’m sure patience would have been tested,” Mangini says. “A lot of it is how you come in, and we didn’t come in winning the popular vote. It’s amazing if you go back and look about how people talked about that hire—it was about as hostile an environment as you could go into.”

On Sunday, Belichick will try and lead the franchise to its sixth Super Bowl victory in 17 years. A win would put him two above the second-most decorated coach in NFL history, Chuck Noll. Just stepping on the field will give him two more Super Bowl appearances than the legendary Don Shula. But 18 years ago, this would have been a fever dream for a mismatched group of coaches and players that struggled to find footing in a new place, surrounded by suspicious fans and media.

So how did that group pave the way for football’s modern dynasty? According to players and coaches involved, it began (and nearly ended) in the locker room.

When Pete Carroll was in Foxboro, from 1997-99, making the final 53-man roster out of training camp felt like getting a job in local government. There was a feeling of tenure, stability.

“With Bill, the final roster didn’t mean anything,” says linebacker Ted Johnson, who played in New England from 1995-2004. “The roster was going to change Week 1, Week 3, Week 4. There was always tension, like your job was never safe or secure.”

Belichick’s terse, closed-door style exposed a mile-wide gap between the veteran players who toiled under Bill Parcells in the early 1990s and the younger class, which was mostly assembled by Carroll and former personnel executive Bobby Grier. Carroll, whose Zen culture encouraging individualism and a relaxed atmosphere would take hold in Seattle a decade later, would have to wait years before his approach was truly appreciated.

“There were two different packs of players when [Belichick] took over,” Max Lane, a Patriots offensive lineman from 1994-2000, says. “You had two different types of players trying to come together and it never really did gel.”

Belichick’s first season was notable more for a sea of transactions, a coach taking a hacksaw to the roster while rewarding certain Parcells dignitaries that would play by the rules. The fluid 53-man roster ended up being a mix of future centerpieces, quiet Carroll loyalists and last-chance veterans holding on.

“I was at the tail end of my career, so I would have played anywhere,” receiver Chris Calloway says. “So, I was just glad they gave me a call.”

The day after Belichick was announced as head coach, the team’s strength and conditioning coach was let go. Less than two weeks later, five-time Pro Bowl tight end Ben Coates was cut alongside six-time Pro Bowl offensive tackle Bruce Armstrong. Coates would go on to play one more year, with the Ravens, and Armstrong would retire. Terry Allen, the team’s leading rusher in Carroll’s last season, was let go in February. Three other players accepted free agent offers elsewhere.

It was, players said, an atmosphere of endless tension. It led to physical, violent practices—football Darwinism—where anyone interested in keeping a roster spot would have to prove it on a daily basis.

Belichick’s ruthless preparation ended up being his only advantage. On Wednesdays during game weeks, he would sit the offense and defense down in a room together and explain the three things each side of the ball would need to do in order to win.

Prior to a Jets matchup, for example, item No. 1 might be that on third down, defensive backs make a concerted effort to hit Wayne Chrebet in the slot. That was his “money down,” and knocking him off his route would significantly derail the comfort and rhythm of the offense. Before a Chiefs game? Double Tony Gonzalez in the red zone. Belichick would finish his session with a guarantee: If you do these things, you will win the game.

“And no s--- man, it just started to work out that way,” says Johnson. “It was then you really saw how much smarter he was than everybody else. He had this way of seeing the game that was better than anyone I’d ever been around. And I’ve been around some great coaches, man.”

Mangini says it was a layered approach. Once the keys to victory were presented, they were hammered endlessly throughout the week with snippets of film or practice drills.

“If we didn’t take care of those things, we were going to lose, and then there wasn’t this big secret about why we lost,” Mangini says. “It’s not like anyone could look back and say, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that.’ The information was there. The plan was there. Then, it just became a function of the willingness to execute the plan.”

Nearly everyone points to Oct. 14, 2001. The 1-3 Patriots had just fallen behind by 10 to San Diego after a Chargers defensive touchdown midway through the fourth quarter in Foxboro. A methodical 15-play drive stalled at the 5-yard line, and New England settled for an Adam Vinatieri field goal with 3:31 left. There was no guarantee they would get the ball back, especially after LaDainian Tomlinson opened the subsequent drive with an eight-yard run. But the defense held, and Brady led an 8-play, 60-yard drive, finishing it with a three-yard TD to tight end Jermaine Wiggins, forcing overtime. The defense got a stop on the first possession of OT, and Brady took New England into field goal range, Vinatieri’s 44-yarder winning it to finish Brady’s first fourth-quarter comeback.

The Patriots would win nine of their next 11 games, including the season’s second victory over Peyton Manning’s Colts and a game against the Falcons in which they hit quarterback Chris Chandler so many times that he was forced from the game.

“We blew the doors off of them,” Johnson says. “We were so aggressive in that game. We blitzed a lot. I mean, we knocked out Chris Chandler, who we used to call ‘Chris Chandelier’ because he got hurt a lot. We got to him all day.”

That playoff run—the “tuck rule” victory over Oakland, an upset in Pittsburgh in which Brady got hurt and Bledsoe threw the game’s only touchdown pass, then upending the heavily favored defending champion Rams in Super Bowl XXXVI—justified Belichick’s process. Players started to understand why he needed to reshape the roster. Why he had to treat them like subordinates. Why the others had to go. There were some, like Lane, who are still disappointed they never got to see it through. Lane had felt the foundation being built and, when reached by a local reporter after his release (Lane broke his leg and was cut following the 2000 season), he made a prophetic statement at the time.

“My first interview after being released, the reporter asked me where I thought the team was going, and I told him, honestly, that I was bummed I got released because I think they’re going to win it all this year,” Lane says. “I don’t know how much I believed it at the time, but I knew they were going in the right direction and it was just sad I wasn’t a part of it. You could tell things were heading in the right direction.”

Lane thought about the 17-year-old kid growing up in New England—a person living their entire life without a whiff of struggle from the Patriots franchise. He called them “spoiled” and noted how many players of his generation, the Patriots who never made it to 2001, still contributed something to the machine that now bulls its way through the NFL annually. It’s bittersweet, how easily everyone forgot what happened before the winning started.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.