If Giants Legend Harry Carson Could Do It All Over Again, He Wouldn't Play Football

About two weeks before the Super Bowl, the Concussion Legacy Foundation, along with a group of doctors and retired football players, held a modest press conference in a banquet room in a hotel in midtown Manhattan. They were there to announce the start of a new campaign with a goal to encourage parents to not allow their children to play tackle football until they turned 14 years old.

Among the speakers that day were Nick Buoniconti, the retired Miami Dolphin who’s been diagnosed with CTE; and Dr. Lee Goldstein, the author of a new study that examined whether people could develop CTE from even just minor hits to the head. Thy all took their turns speaking and it led to a lively discussion about the past and the future of football and player safety.

Hall of Famer Nick Buoniconti: I 'Beg' Parents Not to Let Kids Play Football Until High School

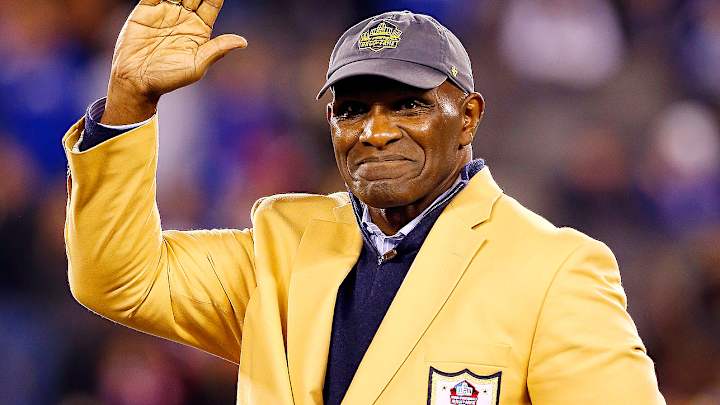

One of the more poignant moments of the press conference came when Harry Carson, the former Giants linebacker, told the room that, given the opportunity, knowing what he know now, he wouldn’t have played football. He wasn’t the first person to say something like that, nor will he be the last. But hearing it come from an NFL Hall of Famer, a Super Bowl champion, a member of the Giants’ Ring of Honor—that came as a surprise.

After the event, The MMQB’s Tim Rohan spoke with Carson about his feelings about concussions, how he tries to help his fellow players, and how he’s dealt with post-concussion syndrome, a malady he’s had to deal with since 1990.

• S.L. Price: ‘I Feel Lost. I Feel Like a Child’: The Complicated Decline of Nick Buoniconti

Rohan: What struck me most was when you said that if you had to do it over again, knowing what you know now, you wouldn’t have played football.

Carson: Oh, I’ve said that over and over and over. When I went into the [NFL] Hall of Fame, I was sitting at the luncheon, and you’re sitting there with all of these iconic athletes. I remember Deacon Jones, he’d get up and say some things and say it in such a tone. [Growing voice:] I’d do it all over again.

Me? I was sitting there like, O.K. I could do it all over again, too.

Then it hit me. You must be crazy. To do it all over again? I came to this realization: there was no way in hell I’d do it all again. That is my truth, that is my honesty. I started [telling people]: no, I wouldn’t do it again. Knowing what I know now? … You only get one brain. Once that brain gets injured, you never know how you’re going to be from that point on.

Rohan: You also said you would refuse to let your grandson play football? How old is he now?

Carson: He’s eight right now. But I’ve been talking about this since he was two. It’s just been talking to my daughter—she knows. She’s been a part of my life and seen the issues of concussions and so forth.

The problem is, her husband played football in the South. And when you play football in the South, it’s one of those things, you want your kid to play and follow in your footsteps.

And I told her, ‘I don’t want him to play.’ I would send her different articles to justify why he shouldn’t play. She got the message. The trick was, how were we going to convince him? Then finally, I stepped in and said, if you think that you want him to play because that’s the only way he’ll go to college, I’ll pay for his college. He is not playing. And so I laid down the law. And I told them, I am going to be the dictator, he ain’t playing—that simple.

Rohan: What’s it been like for you in recent years, dealing with post-concussion syndrome?

Carson: I’m fine, I’m very fortunate. I’m writing a book on solely this issues, but I’m very fortunate in that I had a name to go with what I was dealing with. It didn’t happen until two years after I left football, but looking back at my last eight years [playing], there were all kinds of neurological stuff going on that I couldn’t really put my finger on why.

We would be having a conversation and I would be going, um … um … um. And I’m searching for the word to complete my thought. Here I am, I’m the captain, and I’m standing at my locker going um …um … um, and I’m trying to organize my thoughts. For me, words that I would normally use, I couldn’t grasp those words. I knew something was going on, but nobody else knew.

When I got the name, I was able to educate myself on the issues of post-concussion syndrome. Then I knew how to manage myself. I really thought I had a brain tumor, because I was having all kinds of neurological issues. My muscles would twitch for no reason. I’d be laying in bed watching television and start having headaches. I’d go to the Waldorf [Astoria hotel] for banquets. They’d go around taking pictures and flash photography would be a problem for me.

When I became aware of my triggers and what was going on, I could adjust myself accordingly. I was lucky that I had that information. There are so many other players who don’t have that information. When I talk to a player, I know when he’s dealing with some brain trauma. I can spot it a mile away.

There have been some guys who’ve approached me asking about it. They’re concerned about it. Especially as more and more information came out, guys who have committed suicide.

I had the opportunity to spend some time with Junior Seau, and this was about eight months before he committed suicide. If I had known that he was in that kind of place, I could’ve told him, ‘Junior, you have to learn how to manage it, but you can live with it.’

Terry Long, Andre Waters. Ray Easterling sent me an e-mail, poured his heart out. I passed him onto somebody who could help him, and the ball was dropped, and he committed suicide. I sort of live with that. I tell the other players, if you need help, let me know, I can find somebody who can help you. You can live with it, you don’t have to kill yourself.

Every time a player dies, [Boston’s CTE Center] is on the phone, trying to get the brain. They’re not getting my brain. I’m serious. If you want to know something, ask me now, because I’m a wealth of information.

Rohan: I know it’s a personal decision, but why don’t you want to donate your brain? Would that be too invasive?

Carson: I would just be another brain on the shelf. If you want to know something, ask me. I can tell you right now. I’ve learned how to live with it. Every day is not a great day, but I know how to manage my life.

I eat right, try to keep my weight under control. When I feel like I’m going into a depression, yeah, I’ll eat some fried chicken, something that’s going to make me feel good. You’ve got to do a lot of cardio. … Then I do hyperbaric oxygen therapy. I think that’s something that needs to be looked at as a remedy to traumatic brain injury. It’s time consuming and expensive, because I’m in and out of the chamber like 40 times in a two-week period. It’s not very inexpensive. Not everybody can afford to do it.

Rohan: Do you find it makes a difference?

Carson: It makes a difference for me. I don’t know if it just chills me out. But I feel so much better after undergoing the treatment. The other thing I do, I go to Hawaii a lot. And when I go to Hawaii, that’s sort of like therapy for me. As soon as the plane door opens and I feel the temperature, the weather, I smell the flowers, I feel like I’m in an entirely different place. I look at going to Hawaii as part of my therapy.

Rohan: You mentioned that you can tell when a former player is going through something mentally—how can you tell? What are the signs?

Carson: Well, we talk a lot, guys who played on the 1986 team. We still have a close relationship. The player [who contemplated suicide], I remember George Martin, who was also a captain and a very good friend of mine, he said, can you call so-and-so, he’s having some issues. So I called him up, we’re on the phone.

I’m like, ‘tell me what’s going on.’ He told me what’s going on. Again, pro football players are very proud individuals. He sort of poured his heart out over what was going on. I shared with him my thoughts and we hung up. We talked from like 10 to 11:30 in the morning. Then I got a text from him around 2:30-3 p.m. He said, ‘Thanks Harry, I think you just saved my life.’

MMQB: Did you ever find yourself in a place that dark?

Rohan: Yeah, yeah. It was 1980. I was living in New York, and I thought about driving my car off the Tappan Zee Bridge, you know?

The fortunate thing for me was, I had a daughter and she was like one at the time. And I said to myself, if anything happened to me, what would happen to her? She became my savior. I’ve told that story over and over and over, but that was the truth.

I was dealing with depression. I remember thinking, why am I depressed? I’m playing pro football, I’m making a sh**-ton of money, I have a nice car, everything is good. That depression just sort of engulfed me. Several years later, I think it was 1988, we won a game on a Sunday and this was a Monday. I went to the trainers room and told Ronnie Barnes, the trainer. I said, ‘Ronnie, put me down on the list, I’m depressed.’ He said, ‘Well what do you want me to do about that?’

I said, I’m just putting you on notice, I’m depressed. I don’t think anyone had ever told the trainer they were depressed before.