Jonathan Martin’s Life in the Shadows

LOS ANGELES — On Thursday, Feb. 22, around 7 p.m. local time, Harley Parker was thumbing through his phone, looking at friends’ Instagram stories, when he came across a photo from an old high school football teammate, Jonathan Martin. It was a picture of a slice of pizza from a shop in Westwood, Parker recalls. He sent Martin a direct message—“its so good”—and then kept scrolling through his account.

“Then it just got really intense, really fast,” Parker says.

A tap or two later, he came across a picture of a shotgun, surrounded by 18 rounds of ammo. The post tagged four people: two of Martin’s former Miami Dolphins teammates, Richie Incognito and Mike Pouncey, and two high school classmates. It also tagged #HarvardWestlake, the high school Martin and Parker attended, and #MiamiDolphins. The caption read: “When you’re a bully victim & a coward, your options are suicide, or revenge.”

Parker was a year ahead of Martin at Harvard-Westlake, and they’d started together on the offensive line, Martin at left tackle, Parker at right. Over the years, they lost touch. Parker had reached out to Martin after the Dolphins’ scandal, but never heard back. After seeing the shotgun post, he sent Martin two more DMs:

“dude everything ok? lets chat man”

“gimme a call whenever xxx xxx xxxx. im here for you.”

But Martin never responded. Instead, the photo made its way to the LAPD and the high school. As a result, Harvard-Westlake shut down both of its campuses the next day. “Out of abundance of caution, and because the safety of our students, faculty, and staff is our top priority, we made the decision to close school today,” the school said in a statement.

The LAPD also detained Martin on Friday, Feb. 23, to question him about the post, according to the Associated Press. TMZ reported that the police believe Martin recently purchased two weapons, including the one featured in the Instagram story, and that Martin had a gun with him when the police found him. TMZ also reported that, as of Sunday, Martin was undergoing psychiatric evaluation. As of Wednesday the LAPD investigation was ongoing, and the department declined to comment on what would happen to Martin next. It’s unclear where Martin is now.

Harvard-Westlake reopened on Monday, albeit with an increased security presence. By the end of the week, the school had taken out a restraining order against Martin. The sense of alarm had been heightened because, eight days before Martin’s troubling post, there’d been another mass shooting in the U.S. A disgruntled former student had killed 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. When Martin’s Instagram post went up, the country was still reeling from that attack and engulfed in an emotional debate over the politics of gun control.

People had reason to worry about Martin’s mental well-being. He was the subject of a very public bullying scandal as a member of the Dolphins in 2013. The NFL commissioned the lawyer Ted Wells to investigate the situation, and Wells concluded that there had been “a pattern of harassment” directed at Martin. Two of the players involved in the scandal—Incognito and Pouncey—were tagged in the Instagram post. The Wells Report, as it has become known, detailed how Martin’s teammates routinely made derogatory comments about his mother and sister and about his race and appearance; and degraded him in front of others. At one point Incognito called Martin the n-word to his face. The report also discussed how Martin witnessed and was distressed by his teammates’ inappropriate racial comments directed at an assistant trainer.

The bullying reached the point where Martin left the team in October 2013, in his second year in the NFL, and checked into a psychiatric facility. In the Wells Report, Incognito says that the Dolphins had speculated in jest which of their teammates would “break first” in response to their taunting. They joked that Nate Garner, an offensive lineman who had an affinity for guns, “might ‘break’ by coming to the Dolphins facility and shooting everyone,” the report says. After Martin left the team, Incognito made a few new entries in the offensive line’s “fine book.” He docked himself $200 for “breaking Jmart [Martin],” and he awarded Garner $250 for “not cracking first.” Then Incognito charged Martin more than $1 million for being a “p***y.”

At the time of the scandal, Martin was a starter on the Miami offensive line. After sitting out the remainder of 2013, he spent another year and a half in the league, bouncing from the San Francisco 49ers to the Carolina Panthers, before he retired in July 2015, citing a back injury.

Martin spent his first year of retirement, like a lot of players, trying to find his way outside of football. He returned to Stanford and finished his degree, tested the waters as a public speaker, and began a memoir. He was out in public, telling his story of how he had been bullied in the NFL. Then at some point he retreated from the spotlight—until that disturbing post appeared on his Instagram last week.

Over the past week The MMQB reached out to people who interacted with Martin at various points in his life. There were those who wanted to respect Martin’s privacy, those who had no updates, and those who had no idea what was going on. Four of his high school basketball teammates did not return messages seeking comment. Four members of the 2012 Dolphins declined to comment—and one said that his attorney had advised him to do so. Martin’s former agent, Kenny Zuckerman, said he hadn’t spoken to him in some time.

Andrew Phillips, one of Martin’s close friends at Stanford, simply read off a statement: “He’s a friend of mine, and I’m worried about him, and I hope he gets the care that he needs.”

Martin was less than a month into retirement when he was in the news again, this time on his own terms. In late August 2015 he wrote a 741-word Facebook post detailing his lifelong struggle with depression and being bullied. He traced it to his childhood, when he was 10 years old and his family moved from Pittsburgh to Los Angeles; to his time at Harvard-Westlake, the tony college prep school in Studio City, Calif., where he considered himself an outcast; and up through his time with the Dolphins. The post, written in the second person, dives into the dark part of Martin’s psyche. It made headlines as Martin revealed that he’d attempted suicide “on multiple occasions.”

But Martin ends the post on a positive note, saying that he’s decided he’s going to tell his story and spin it into a positive, in hopes of helping others struggling like him. “You let your demons go, knowing that, perhaps, sharing your story can help some other chubby, goofy, socially-isolated, sensitive kid getting bullied in America who feels like no one in the world cares about them,” he writes. “And let them know that they aren’t alone.”

Speaking out wasn’t Martin’s first choice, apparently. After the Dolphins scandal, he later told USA Today, he wanted to “disappear.” “I had a couple people mention it to me after the whole ordeal like, ‘That is a unique story. No one else has that story.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, but it sucked, and I want it to go away, and I want to disappear, and then I was like, ‘OK, I’m not gonna disappear. I’m still gonna wake up and have to do something. My name is still gonna be Jonathan Martin. I’m not gonna change my name. People are still gonna recognize me, so what am I gonna do about it?’ Why not do some good instead of wallowing in the past?”

A day after the Facebook post, the Associated Press reported that Martin was working on a memoir with Atria Books, an arm of Simon & Schuster. The deal was reportedly worth sixth figures, and the wheels were in motion. Martin had already lined up high-profile literary agent, Steve Ross of Abrams Artists Agency, and a co-writer, the author and career coach Hilary Beard. They even had a title picked out, too: The Courage To Walk Away.

“I was aware of Jonathan Martin, being a football fan, so I was curious about the juicy parts of his story,” says Todd Hunter, the Atria editor who worked on the book. “But what attracted me more than anything, it seemed as if after leaving the NFL he [was] a better man for it.” Ross, the literary agent, wrote in an e-mail that he was drawn to the project because he thought Martin would inspire the millions of people that “are bullied and feel cloistered and alone,” as a football player who faced those feelings and overcame them.

Back then you could imagine Martin as the face of a nationwide anti-bullying campaign. Hunter says they discussed releasing the book in October 2016, so it would coincide with National Bullying Prevention Month. Now, Martin and Beard had to sit down and start writing.

As Hunter said, at the time Martin seemed to be doing better. He was working toward finishing his college degree and living in Palo Alto, the place where he built himself into a two-time All-America and where he always felt at home. “Stanford is a very special place filled with people with all kinds of diverse backgrounds,” Martin would say at one of his talks. “Lots of weird people, lots of nerds, and I felt like I fit in with all the weirdos and nerds.”

“He was outstanding here at Stanford,” says football coach David Shaw. “He did well in school. He built himself up to be one of the outstanding football players in America. He had great relationships and friendships on our team and on campus. … The overriding feeling at Stanford is, you get here, you get support, you find your way, and you develop yourself as a person.”

In May 2016, USA Today wrote a glowing profile of Martin. In that story, he said that graduating from Stanford—with a degree in Classics, with a focus on Ancient History—was one of the proudest moments of his life. He said he’d attended Stanford football games in the fall of 2015 and tailgated like a normal student. “I get why people are always at football games,” he said. “It makes sense.” Martin also confessed that he’d thought a lot about returning to the NFL, but decided now wasn’t the right time.

On an October weekend in 2015, Martin returned to Harvard-Westlake to be inducted into its athletics hall of fame. They called him onto the field, read a brief bio and handed him a plaque adorned with varsity letters. Martin stood under an arch of red, black and white balloons—the school colors—and smiled for pictures with the athletic director. Afterward he chatted with Alex Holmes, another hall of fame inductee. Eventually, the conversation the drifted to Incognito, Martin’s counterpart in the Dolphins bullying scandal. Holmes had been teammates with Incognito on the St. Louis Rams briefly in 2006, and they’d stayed in touch. “I’ve been friends with Richie for a long time, and I know Richie’s humor,” Holmes says. “I just said [to Jonathan], ‘I’m sorry it got to the point where it affected you.’ That was the extent of the conversation. I didn’t sit there and chat with him forever about that. … There didn’t seem to be any issues when I met him, but I only met him once.”

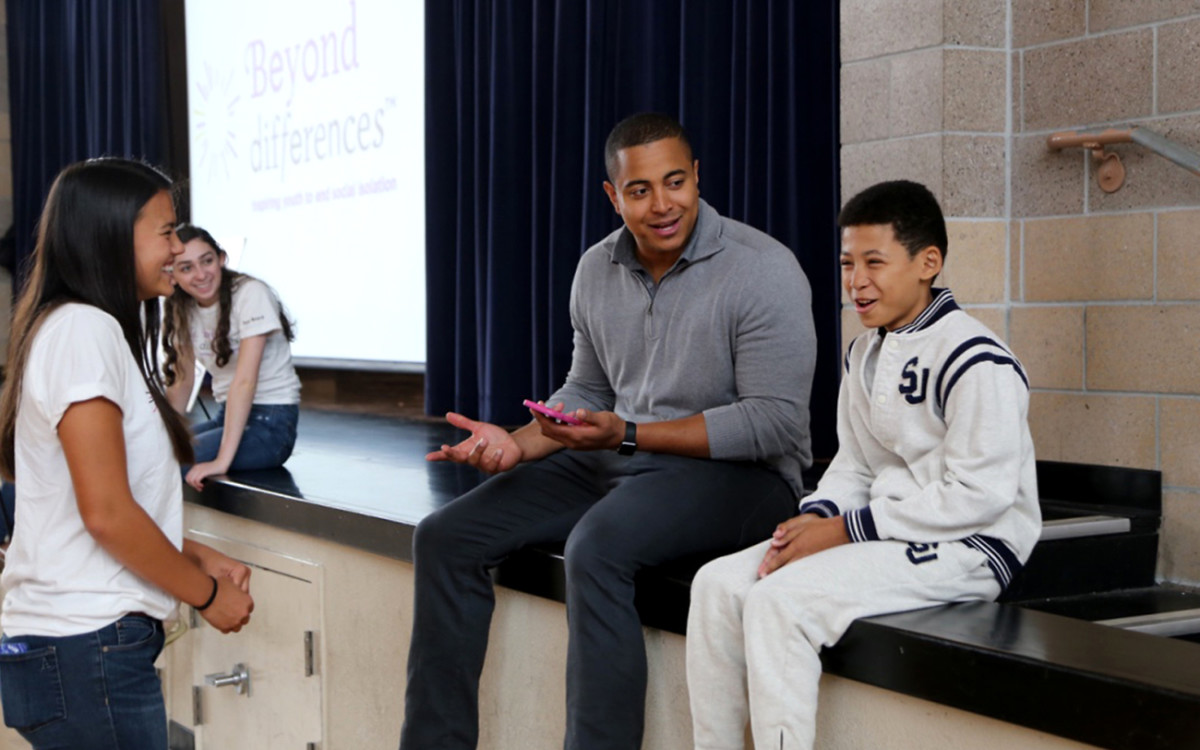

By that point, Martin seemed somewhat comfortable talking about the Dolphins situation—at least enough that a friend of a friend put him in touch with Laura Talmus, the founder of a Bay Area non-profit called Beyond Differences. Talmus had read about Martin’s experience and seen the Facebook post, and she asked him if he had any interest in public speaking. Beyond Differences focuses on social isolation, children feeling left out—which it says is a precursor to bullying—and Martin seemed like a great fit.

By the spring of 2016, Martin had agreed to be a “national spokesperson” for Beyond Differences. Between March and May of that year he visited at least four middle schools and appeared at two adult-oriented events on the organization’s behalf. USA Today shadowed Martin on one of his trips, reporting that Martin visited as many as 10 schools.

At the Beyond Differences stops, Martin mostly repeated the same story — a lighter version of what he’d written in the Facebook post shortly after he retired. He’d talk about growing up in Pittsburgh, where he was known as “the rich white-black kid” because his parents had good jobs (his father is a university professor and administrator, his mother a lawyer) and he read books. Then he’d talk about moving to Los Angeles, where he was “the poor black kid” going to Harvard-Westlake along with, as he put it, “the children of Hollywood’s rich and famous.” He’d tell audiences how he’d recently discovered he had a predisposition to depression and anxiety, and how he constantly felt “trapped” in his own head. “Little things that didn’t bother most kids—teasing or whatever—would stick in my mind,” he said at one event. He’d tell them about how he became a bully, in response to others bullying him. For the older crowds he might get into the Dolphins situation. Then Martin would urge the teens and pre-teens to “be kinder and more inclusive with one another, and make sure that everyone feels accepted,” Talmus says.

By all accounts, Martin was a great spokesperson. The children always swarmed him asking for photos and autographs. “I watched it, and the kids were all really glued to what he said, as he shared a very personal story of being their age,” says Barbara Zamost, the public relations director for Beyond Differences. “It was right on the money. It was the kind of story, you could look around and you could see it really hit home with some of those kids.”

Zamost received a few media requests for interviews with Martin, but he declined all of them except for USA Today. “I think he was doing it from the right place,” Zamost says. “He was doing it to help the kids not feel the way he felt.”

Later in 2016, Martin moved to Southern California. He did no more appearances for Beyond Differences, and Talmus, the founder, says she simply lost touch with him. “I’m heartbroken that he’s going through this right now, personally,” she says. “But to be quite frank, I haven’t spoken with him in two years.”

When Martin gave his talks for Beyond Differences, for the most part he would leave out the grim details of his Dolphins experience, his depression and his suicide attempts. But he did not leave them out of his book. Hunter, the Atria editor, is one of the few people to have read Martin’s memoir, which gave him a deep look into Martin’s psyche. Just as in the speeches, he says the memoir traced Martin’s problems back to his childhood in Pittsburgh and Los Angeles, and the move from one city to the other. “I didn’t know how far back his angst and depression goes,” Hunter says. “In that shift was when a lot of anxiety set in, a lot depression set in.” All of the issues that came afterward, Hunter says, were “just a symptom of something that started early on.”

Martin has spoken publicly, here and there, about those issues. In the 2015 Facebook post, he wrote that growing up not fitting in “nearly destroy[ed]” him. “It takes away your self-confidence, your self-worth, your sanity,” he wrote. Then he lamented the fact that he never confronted the bullies of his youth, never stood up for himself. He blamed the “whitewashed, hermetically-sealed bubble” he grew up in for not teaching him to be tougher, more assertive.

That sentiment was apparent in an April 2013 text message Martin sent to his mother, which was included in the Wells Report. “I figured out a major source of my anxiety,” he wrote.” I’m a push over, a people pleaser. I avoid confrontation whenever I can, I always want everyone to like me. I let people talk about me, say anything to my face, and I just take it, laugh it off, even when I know they are intentionally trying to disrespect me.”

Martin later told her, “High school still and will forever haunt me.”

The memoir also dove deeper into the Dolphins situation. “It detailed what happened in Miami to a certain extent,” Hunter says. “[But] it detailed more about what happened afterwards, what he went through when he left the facility and actually went back to his house, and how dark it had gotten for him, where he was actually contemplating suicide.”

In the Facebook post, Martin touches on the depth of his depression from his time in the NFL. “Your self-perceived social inadequacy dominates your every waking moment & thought,” Martin writes. “You’re petrified of going to work.” It reached a point where he was abusing alcohol and marijuana, sleeping for as much as 16 hours a day, and having trouble focusing. He told USA Today that after games, he’d sit on his balcony and stare into the distance “for hours” on end. In the Wells Report, Martin says he would often arrive at the Dolphins facility “silently repeating the mantra, ‘just get through the day.’ ”

By the time he wrote the memoir, though, Martin had apparently gained some more perspective about that time in his life. “He made a concerted effort not to make it seem like Richie Incognito and [Mike] Pouncey—not to make it seem like it was all their fault,” Hunter recalls. “He made an effort to take some of the responsibility for what had happened. It seemed like he had that level of self-analysis. He was attempting that. That’s what I got from reading it.”

“He took sole responsibility for his own choices and behavior, and was fearless about critiquing himself to the same degree he did others,” Ross, the literary agent, says.

The Wells Report does note that there was some gray area in the Dolphins bullying scandal. At one point, Martin and Incognito were close friends. “Many Dolphins players reported that Incognito and Martin seemed inseparable; some said they viewed Martin as Incognito’s little brother,” the report said. And Incognito has claimed that Martin, too, was complicit in the boys-will-be-boys culture.

Hunter says that, in one part of the book, Martin “wrote this sort of letter to the NFL and the people who have supported him over the years and sort of apologized for not handling the situation in the best way.”

Hunter recalls that, eventually, Martin and Beard, the co-writer, turned in “about nine chapters,” which could be considered a full manuscript. But Hunter had several edits he wanted done, gaps he wanted filled. “There were just elements of it that weren’t quite complete,” he says. “As an editor, I was trying to make what was presented to me better than it was. But I realized the reason I couldn’t make it look that good was because Jonathan was skipping out on stuff. He wasn’t digging deep enough to make the book fulfilling. I needed him to dig a little deeper to make it make sense to the reader.”

Ross, the literary agent, takes issue with that characterization. “Jonathan was not told to dig deeper in the sense that he wasn’t being introspective enough,” Ross says. “Perhaps there might have been a minor detail or point here or there that merited elaboration, but overall he was tremendously honest and forthright about his inner life, surprisingly so—almost shockingly so for a professional athlete. It is inaccurate and potentially harmful to portray him as not having dug deep—for a 25-year-old he dug deep as hell, in fact.”

Whatever the case, Martin never finished the memoir, and the manuscript remains unpublished.

“He said he wasn’t quite ready to deal with some of the stuff that he had written,” Hunter says. “I felt that writing [the book] maybe re-triggered some deep emotional issues. He might not have been quite there. At the time, that was the conclusion I came away with. It was like: He wasn’t there. He wasn’t at a place where he could write something like this and handle it in the best way, so it was probably in his best interest actually to not publish it.”

Ross isn’t entirely sure why Martin backed out, but he has theories. “Perhaps he just wanted what he perceived as a normal life, and didn’t think it would be awaiting him on the other side of publishing such a heartfelt and candid book,” Ross says. “Perhaps he was concerned about hurting family members or former teammates or friends.” Nevertheless, Ross maintains that, at the time, the book was nearly complete. “If he’d wanted to go ahead and publish the book, it was right on the verge of being ready to be published,” he says.

Ultimately, Atria and Martin went their separate ways. “He did it honorably, with apologies for the inconveniences and repaying the publisher whatever monies they’d paid out to date,” Ross says. If things change, Hunter told Martin, you can always re-submit.

Hunter did not hear again from Martin, who seemed to fade from the public eye from that point. He hasn’t done an interview with a major publication since that USA Today story in May 2016.

“I would be curious,” Hunter says, “what happened to him since we had our thing in 2016, until now?” Hunter says he was surprised when he saw Martin’s troubling Instagram post last week. Then he pauses. “Well, surprised and not surprised. Surprised, in that one would think and one would hope that he was doing better in his life. But not surprised, because I perhaps have a more intimate view of Jonathan given what was presented in the memoir. Seeing what happened, you say to yourself, I kind of see why it makes sense, given where he’s come from. It’s just unfortunate.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.