Peter King’s Favorite Stories, from SI and The MMQB

I’ve always thought my job as a writer had three parts:

1. Report the heck out of a story.

2. Take the readers where they cannot go.

3. Write quickly and be smart. Think hard about the words, but don’t be obsessive about them. Different ones work fine.

In 29 years at Sports Illustrated and The MMQB, I think I wrote some good stories. I always tried to improve as a writer, and with stories I was hugely proud of I took great care in trying to make every sentence count. But I wasn’t Frank Deford or Rick Reilly or William Nack. I was best at my ability to make people tell me things, and then report on those things to make them meatier, and then get them to you.

Part of what I tried to do—and what I tell young journalists sometimes now—was work hard to find the good stories, and work hard to convince people to let me tell those stories. In the first three months of 2017 I worked on the 49ers to let me into their draft process, so I could report and write on John Lynch’s first draft as a GM. Fortunately for me, they said yes. More fortunate for me, the Niners turned out to be a major player in the first round that year. And even more fortunate for me, John Lynch and Kyle Shanahan were absolute gold—open, honest, talkative and emotional when the time called for it. Stories are so often like snowflakes. So different, and at the start of the snowstorm, you don’t really know how much you’ll get and what the storm’s going to look like. When the Niners’ brain trust ducked into Lynch’s office less than an hour before the start of the 2017 draft, and Lynch told cap guy Paraag Marathe to see if he could squeeze a little more out of Chicago GM Ryan Pace, and you listen in as the trade is bartered, well, that’s why we’re in this business. To be on the front line, and to tell you all about it.

Last week I wrote my final MMQB column here. Today I write my final entry for this franchise. It’s my selection of my favorite stories over my three decades on a great team. I hope you enjoy them on this Memorial Day … and what I hope even more is that you learn from them something more about the sport you love.

All of the following stories have links to the SI Vault or The MMQB versions click on the headline, subhead or link), with one exception: a softball story from the early days of the MMQB column. That appears in its entirely here.

Nov. 26, 1990

Busman’s holiday

A trip across I-80 from California to the New York City with John Madden

LINK:www.si.com/vault/1990/11/26/123146/busmans-holiday-coast-to-coast-commuter-john-madden-likes-what-he-sees-as-he-rolls-across-america-in-his-suite-on-wheels

I’m an Americana guy, but I’d never driven or been a passenger in a vehicle that traversed the United States. I wanted badly to do so. So in my second year writing for Sports Illustrated I proposed this story—a trip on the Madden Cruiser from West Coast to East with the biggest analyst in football—to John Madden and agent Sandy Montag. Madden said yes. We left from his home in Pleasanton, Calif., at noon on a Wednesday, arrived at his apartment at The Dakota in Manhattan at 10 p.m. Friday, and he did the Giants-Cowboys game a day and a half later at the Meadowlands. Fifty-five hours, 3,016 miles, and I was so bummed when it was over.

Madden, who preferred bus air travel, on what it was like to get to know I-80 the way most of us know Main Street in whatever town we live in:

“We had to stop in Beaver Crossing, Neb. [pop. 480], once, to use the phone for a radio show,” Madden said. “It’s near Lincoln. Some guy comes across the street from a gas station and introduces himself. Roger Hannon. He was the mayor, and it was his gas station. The next thing I know, we’re in front of city hall, and the people start coming out, and they want to see the bus. One woman brought me a rhubarb pie. I didn’t even know what rhubarb pie was, but it was great. The whole town came out. There were only about 10 of them, but they were the whole town. I remember asking them, ‘What do houses sell for here?’ They said the last house that sold was right down on the corner—three bedrooms, three baths, a picket fence, for $8,000.”

Two days after Madden’s visit to Beaver Crossing, the Omaha World-Herald ran a story on page 3 with the headline: MADDEN STOPS TO USE THE PHONE.

What fun that was.

April 29, 1991

Big D Day

Inside the Cowboys draft process as they built a champion—and inside the draft room.

How times have changed. Twenty-seven years ago, the subhead on this Sports Illustrated story was: “The Dallas Cowboys went on the attack in the NFL draft and took all the right prisoners.” Yikes. Might not look so good today.

What I’ll always remember about this story: The Cowboys went out as a staff to scout the biggest college players, and Jimmy Johnson hoped the coaches’ experience in the college game (most came with him from college to the NFL when Jerry Jones hired him in 1989) would bear fruit. He hoped they’d be able to probe their friends who still coached in college and find out the truth that other scouts might not be able to learn.

On this trip, there was a defensive lineman, Mike Jones, from North Carolina State, who puzzled the Cowboys. Talented, but he wasn’t in the game on every play. Odd, for a guy who might be a first-round pick. Butch Davis, a real digger on the staff, got one of the Wolfpack assistants to say they questioned Jones’s toughness. When Davis delivered the information to Johnson on the Cowboys’ plane, you’d have thought they just scored a touchdown to beat the Giants in the final minute. That was a big way the Cowboys got good. They had more info than other teams.

After the draft, Johnson told me, “We’ll be good, big-time good.” After going 8-24 in the first two years of the program, the Jerry Jones-Jimmy Johnson Cowboys won two of the next three Super Bowls. It ended in divorce, as we all know, but it was a compelling five-year run. Loved covering that team, with all the drama. And wins.

March 15, 1993

Trip to Bountiful

Reggie White leads the first-ever class of NFL free-agents.

For the first decade that I covered football, free agency didn’t exist. The NFL establishment treated it like the plague. When I covered the Giants in the ’80s, GM George Young used to rail against it weekly. Daily, sometimes. “In baseball, you can just plug in one second baseman on another team, “ Young would say. “They all do the same job. You can’t do that with guards! The job is different, the terminology is different from team to team!”

But modernity was coming. Some in the league, like powerful PR man Joe Browne, loved the specter of March Mayhem so that football could be in the headlines in the offseason. He believed free agency would be good for the game, and for its business. And here it was. Free agency was won by the players in a Minneapolis courtroom in September 1992. It started in March 1993. The first class included the best defensive player in football, Eagles defensive lineman Reggie White, and teams were falling all over each other to get White to simply visit them. White’s agent, a young Jimmy Sexton, was cool with me trailing the traveling circus from city to city (I did three stops) along with White, wife Sara, and another client, guard Harry Galbreath.

I met them in Tennessee before the trip. White seemed blown away by it all. He told me he was worried that with many of the teams chasing him, signing him would signal, “Our savior has arrived.” White had been on a great defense in Philly, and he wanted to go where it wasn’t all about him. He was a nervous man, flying into Cleveland to meet coach Bill Belichick and owner Art Modell, to explain why this was the team for him. First, Modell told me he needed to understand this complex system of player movement. “Our first draft choice is going to be from Harvard Law School,” Modell said, “and one of the clauses in his contract will be to teach me this new thing.”

SI’s managing editor, Mark Mulvoy, was behind a smart cover. There was White, shirtless, and jerseys of various suitors, as in a doll kit. On the cover you could recognize unforms from Washington, Philadelphia, Atlanta, the Jets, Cleveland, Phoenix, Detroit … but no Green Bay.

Guess where he ended up signing.

Oct. 30, 1995

Countdown

I spent a week inside the Packers, preparing for a big game.

You know what still pains me, looking back on this story? How short it was. Just 4,257 words to cover seven days inside a football team. In those days (and still), every page in the magazine was precious. Every word counted. As it should. But I remember arguing for more space that week. “Nope,” I was told. “We got a great Bo Jackson story this week.” I had asked around, and I believe this was the first time in the history of the magazine that a writer had spent a game week inside an NFL team, and I was jonesing for the cover

So it was short, and it wasn’t the cover. Bo was. Boy, was I pissed off. As pissed as I ever was in 29 years at SI. Just 608 words per day. Twelve paragraphs for game day! As you can tell, 23 years hasn’t been enough time to get over this. Because in those days, what you didn’t write just died. No place for it.

Okay. Breathe.

Anyway, so many of you have told me over the years you read this story and really loved it, and I appreciate that. It was a ball. Tremendously educational on football, and full of life otherwise. One memory I’ll never forget: Brett Favre sleeping in quarterback meetings run by Steve Mariucci. And farting a lot. Like, farting incessantly. A few times the time the door got opened and fanned, trying to get the fumes out. Another memory: On Thursday night, Favre took a first gift over for the Mariucci family’s newborn, Brielle. He lifted her up over his head and said, “Hey Brielle: Horse walks into a bar. Bartender says, ‘Hey, why the long face?’ ‘‘

Brielle is 22 now, a Boston College graduate. I wonder if she knows Brett Favre lifted her high into the sky at four weeks and told her a bad joke?

Fun story. What it taught me: Access to inside football is irreplaceable.

Aug. 4, 1997

Young and Restless

Steve Young is one heck of a humanitarian … with one big hole in his life.

Talk about an enlightening, uncomfortable, rewarding story. I flew with Young to Navajo and Hopi reservations and saw him try to connect with kids without much hope. Then we went to his annual golf tournament near Salt Lake City, which was different from many of these athlete/coach affairs I’ve attended. No liquor. “This could have been the Von Trapp Tournament,” I wrote, with all the kids running about. This story was about Young the player but more Young the person, and Young the seeker of a family. At 35, time was running out for him to find the right woman and, in Mormon tradition, start a big family. That was the uncomfortable part. In his foursome, the guys were wondering, When are you going to find someone, fella? I overheard one golfer say: “Jeez, Brigham Young had 14 wives.”

“I think it’ll happen,” Young said. Three years later it did. Young got married, and they have a family, and he seems to be living happily ever after. Couldn’t happen to a better guy—but on this day in Utah I remember feeling awful for him, as the biggest star in the Mormon sports universe, that everyone was looking at him and wondering why he wasn’t hitched.

May 5, 2003

Monday Morning Quarterback: Prep Squad

I love high school sports, and this game (selfishly) explains why

The following is the original post from 2003.

MONTCLAIR, N.J. — On Saturday night, about 9 o’clock, Montclair High School softball historian/superfan Jim Zarrilli asked me: “Well, Pete, you’ve been to a lot of sporting events in your life. Does this one rank in the top five?”

“Jim,” I said, “this might be in the top one.”

Oh no. He’s doing it again. He’s writing about his daughter’s softball team! At the top of the column! Why is he putting us through this again? He just can’t help himself when it comes to writing about this personal stuff, can he?

No. He can’t.

I wrote about softball at the top of the MMQB column a year ago. Yes, there are a few other things to talk about, such as draft leftovers, and Mike Price and Larry Eustachy, which you can do by scrolling down a bit. But this is my week to chronicle a compelling event in a lot of lives, the big Essex County Softball Tournament quarterfinal match between third-seeded Montclair (12-4), with your favorite southpaw, junior pitcher Mary Beth King, and sixth-seeded Cedar Grove (13-4). This is a rematch of the game I wrote about last year in the aforementioned column, when Mary Beth and her good friend and longtime offseason- pitching-lesson partner Kaitlyn Sweeney of Cedar Grove dueled and Montclair came out with a 2-0 win. Kaitlyn’s a great kid. I coached her on a summer team when she was in seventh grade, and our families are friends. I was proud to write her a letter of college recommendation, and she’ll be going to Penn State in the fall.

Now for the rematch. I will understand if you scroll down, by the way. But if you stay, I hope at the end of this yarn you can say, “That was worth three minutes of my time.”

County tournaments in New Jersey are special, and the one in our county, a few miles west of the Meadowlands, seems particularly intense. Many of the girls grow up playing softball against the same towns in travel leagues and higher-profile summer ball. Last Monday, Montclair beat Belleville 2-1, and Mary Beth pitched. She’s been playing against Belleville since fifth grade and pitching against Belleville since sixth grade, and she’d never been on a winning side against any of the Belleville teams. This wasn’t a county tournament game, but after years of playing the same kids, all these games against local foes become a big deal.

Anyway, these games draw 200 or 300 people minimum, and my guess is that Saturday afternoon’s contest at Montclair’s field drew about 400. These county neighbors are two excruciatingly evenly matched teams. Both play low-scoring games, boast good infield defense and try to make their limited hits count. I was expecting a 2-1 game, or even 1-0. On the mound for Cedar Grove was its all-time winningest pitcher, Sweeney, who is tall and angular, technically perfect and first-team all-county. It also had the returning all-state shortstop, Holly Calcagno, who is the best hitter Mary Beth has ever faced. Calcagno is headed to UConn on athletic scholarship. We have the all-county catcher, Jess Sarfati, who’s headed to play at Bates, and a Jeteresque shortstop, Kaitlin Giannetti, who is headed to play soccer at Johns Hopkins. And Mary Beth, who entered the game 6-2 with a 0.79 ERA. She’s a gritty kid. The rest of the team plays pretty sound behind her and she doesn’t let the dam burst.

Cedar Grove in black and gold, on the first-base bench behind the clamshell backstop. Montclair in white tops and blue shorts, third-base side. The noise started from both benches at 4 p.m., and I don’t remember it stopping until it was near sundown.

Calcagno led off, and Mary Beth went fastball-change to start her 0-2. But on a 2-2 pitch, Calcagno hit a bomb 15 feet over our left-fielder’s head. Julie Vreeland went back and almost got it, but it ticked off her webbing. Triple. “I threw a riser that just didn’t rise,” Mary Beth reported later. Calcagno hopped on the third-base bag four times, clapping her hands hard. Our infield played in to cut the run off (one run is everything in this game), and their second hitter blooped a humpback infield pop that landed almost on second base. Euphoria for the Panthers. The game was three minutes old and they had the golden run. Mary Beth finished the inning strikeout-strikeout-popout, but after a half-inning, Mary Beth thought, “We might be in trouble.” Giannetti took care of that. Leading off the Montclair first, she lined a screamer up the left-center-field gap. It got by their left fielder, and she sprinted around the bases. Homer. Wow. Two leadoff batters. Two runs.

Amazing how symmetrical this game became. No runner reached third over the next five innings. Sweeney has an outside sinker that baffles righty hitters, including Mary Beth, who entered the game 18-for-39 at the plate but went strikeout-single-strikeout in her first three times up. “Kaitlyn is incredible,” Mary Beth said at dinner that night. “She’s the best pitcher I face.”

In the seventh, doom for the home team. With one out, a Cedar Grove batter reached on an infield miscue. The Panthers followed with a cue shot over the second baseman’s head and an infield single. Cedar Grove, 2-1. Fifteen kids on their sideline broke the high-jump record when the go-ahead run crossed home plate. Now, with two out and a runner on second, Calcagno came up. Walk her, I’m thinking. WALK HER! Our coach, Tricia Palmieri, has instilled something in our kids about the other team never, ever, ever being better. Calcagno was triple-popout-single to that point. Mary Beth had her 2-2, Ping! Sharp one-hopper to Giannetti, throw to first, inning over.

Bottom of the seventh. Game and county pride on the line. Walk, sacrifice. One out. Margot Vreeland, our senior right fielder and resident pepperpot, then lined a sinking shot to center. Their centerfielder went for the shoestring catch (our runner was holding), and the ball managed to get past her. Euphoriaville!

Softball’s a seven-inning game, so now it’s extra innings. In this sport, it’s not unusual for pitchers to throw into extra innings. And in this game, no reliever ever warmed up. I don’t buy the claim that kids can throw unlimited innings, and neither does Mary Beth’s orthopedist, who has treated her for a broken pitching elbow and rotator cuff tendinitis. But neither coach thought of removing these girls, and I think they would have had black eyes if they tried.

Scoreless eighth. In the ninth, Mary Beth got into the jam of all jams. She hit a batter (“No I didn’t; it hit her bat,” she said later, but the ump’s vote was the only one that counted), and then walked her first batter of the game. Then, a perfectly placed bunt. Bases loaded, no outs. Tension on the Mounties’ side. Glee on Cedar Grove’s, whose players could smell their biggest win of the year. Next batter: Pitcher’s best friend, a little pop to the first baseman. Next batter: Hard ground ball eight feet to first baseman Jess Giammella’s right. She dove, speared the ball and, from her knees, sidearmed a throw home, where Sarfati waited with her right foot on the plate for the force. The ball was low and way outside. Sarf stretched, and stretched, and here came the go-ahead run, and Sarf scooped a one-hopper out of the dirt, almost doing a balance-beam split with two fibers of her right cleat touching the black of home plate. Time stopped. The ump went around to the side, stared at the foot, looked for the ball ... AND RUNG HER UP! “OUTTTTTTT!”

You think it’s over? It ain’t over. Now for Calcagno. No place to put her. Strike, outside corner. Ball, high. “Every pitch I throw now is a screwball,” said Mary Beth, who just wants every ball to tail away from our county’s Dot Richardson. Next pitch: PING! Another hard grounder to short. Giannetti guns her down at first. We’re out of it. Massive hugs on the Montclair side. The Cedar Grove coach, Rob Stern, looks up at the sky as if to ask, “Hey God, you couldn’t just give me one hit from the best hitter in New Jersey? C’mon!”

Sweeney was rolling. She had a 1-2-3 ninth. Mary Beth and Kaitlyn posted 1-2-3 10ths, and Mary Beth had officially pitched longer than in any other game in her life. In the 11th, Cedar Grove had a runner on second with one out, and our frosh second-baseman, Courtney Taylor, grabbed a looper at the second-base bag and touched second for the double play. We went to the 12th. Uh oh. Cedar Grove, with one out, picked up an infield single, followed by its second walk of the game, and a bunt single. Jammed again. No mas! No mas! We can’t take it anymore. Mary Beth had their third hitter 1-2. Sarf set up outside. Mary Beth painted the black. Called strike three. Next kid: Jammed inside on the first pitch. Pop to left.

I mean, does Mary Beth King have nine lives or what?

We got ‘em 1-2-3 again in the 12th. Now it was the 13th. That’s two games. Mary Beth was at 166 pitches. Luckily for her, it was a 1-2-3 top of the 13th.

Bottom 13. One out. Mary Beth (1 for 5, two strikeouts to that point) up. She looked beat. And Sweeney was on fire. She’d retired 14 in a row with that nasty outside sinker.

“There was no way I could go out there and pitch any more,” Mary Beth said later. “My arm was dead.”

“Really?” I asked. “Would you have gone out again?” “Of course,” she said. “What choice did I have?”

So she started thinking about her at-bat. “Every time up, I’d taken the first strike,” she said. “Kaitlyn’s smart. She must have caught on, because every first or second pitch was a perfect strike, the kind of strike where you’re watching the game and you say: ‘I can’t believe she didn’t swing at that pitch!’ So I figured, I’m swinging at the first pitch, wherever it is.”

It was right over the heart of the plate. PING!

Up the right-center-field gap, splitting the outfielders. Mary Beth steamed into third. Standup triple.

Well, the bleachers shook and our bench exploded. Mary Beth just stood on third. A little pumped, but basically just catching her breath. I have often wondered this about her: Where does the cool come from? The reserve? Wherever it comes from, I’d like to patent it.

Now Meg Mylan, our third baseman and third hitter, stood in. Infield in. Kaitlyn threw, and Meg popped one just beyond the baseline between second and first. Their fielders sprinted for it. It kerplunked into the clay. Mary Beth steamed home.

Ballgame. Montclair, 3-2.

Two Cedar Grove gloves slammed to the ground. The Montclair side sounded like a jet engine. Mary Beth made a beeline for Meg and leaped into her arms. “YOU THE MAN!” she yelled. Then the Montclair team caught up to the two heroines and pummeled them.

Two teams. Two pitchers. Three hours. Four hundred hoarse voices. One incredible bang-bang force out at home.

One hundred batters. Dead even after 98. The 99th got a pitch six inches more to her liking than before. Six inches. The 100th locates a blooper perfectly. And that is how drama unfolds.

There is nothing like high school sports. Anywhere. Boys, girls, it doesn’t matter. They play with the same ferocity. The joy for the winners is the same. The tears for the losers are as wet. You can’t simulate these experiences as kids get ready to go out into the world. You think Kaitlyn Sweeney’s going to be afraid the night before a big final at Penn State next year? She’ll laugh at being afraid. She’ll prepare the same was she prepares to be a great pitcher, and she’ll win the test.

Fifteen minutes after the game, Mary Beth was pulling off her cleats. A Bazooka comic fell out of her shoe. “Here, coach,” she said, handing Palmieri the comic. Seems that before the game, the coach had opened a piece of gum, liked what the fortune said, and told Mary Beth to hang onto it. After the game, Palmieri was hanging onto the comic, her souvenir for the day. In exchange, she handed Mary Beth the game ball.

The fortune read: “The ones who prepare are the lucky ones.”

And that is my softball story for the year.

Postcript to this column:

Last week I sent this column to Mary Beth—now working on the social media team at Microsoft and living in Seattle—and she read it. I’m not sure she even read it at the time I wrote it; she was never much of a hey-I-did-it kid.

She emailed me back, saying it was a fun memory to recall, and saying she recently got a nice compliment at work from a Microsoft executive after a laborious period preparing and producing a new product. Wrote Mary Beth:

“Afterwards he sent a mail to my boss saying something like, ‘I can’t believe how cool Mary Beth was under pressure. This wasn’t even her announcement to lead but she was the calming voice of reason in the room.’ Things like that make me very grateful that I played competitive sports. I had to learn at a young age how to be cool under pressure, and it really does translate to real life.’’

Now that’s cool email to receive from a dad who just might have been a little too sports-conscious with his two daughters. Laura, 34, lives in San Francisco and has a good job with Twitter, and I believe learned much from the ups and downs of high-level field hockey and softball, as did Mary Beth, now 32. Sometimes I wonder if I was too crazy about it. Good to know that at least I did not send either off the deep end.

Aug. 9, 2004

Master and Commander

How Belichick got to be Belichick

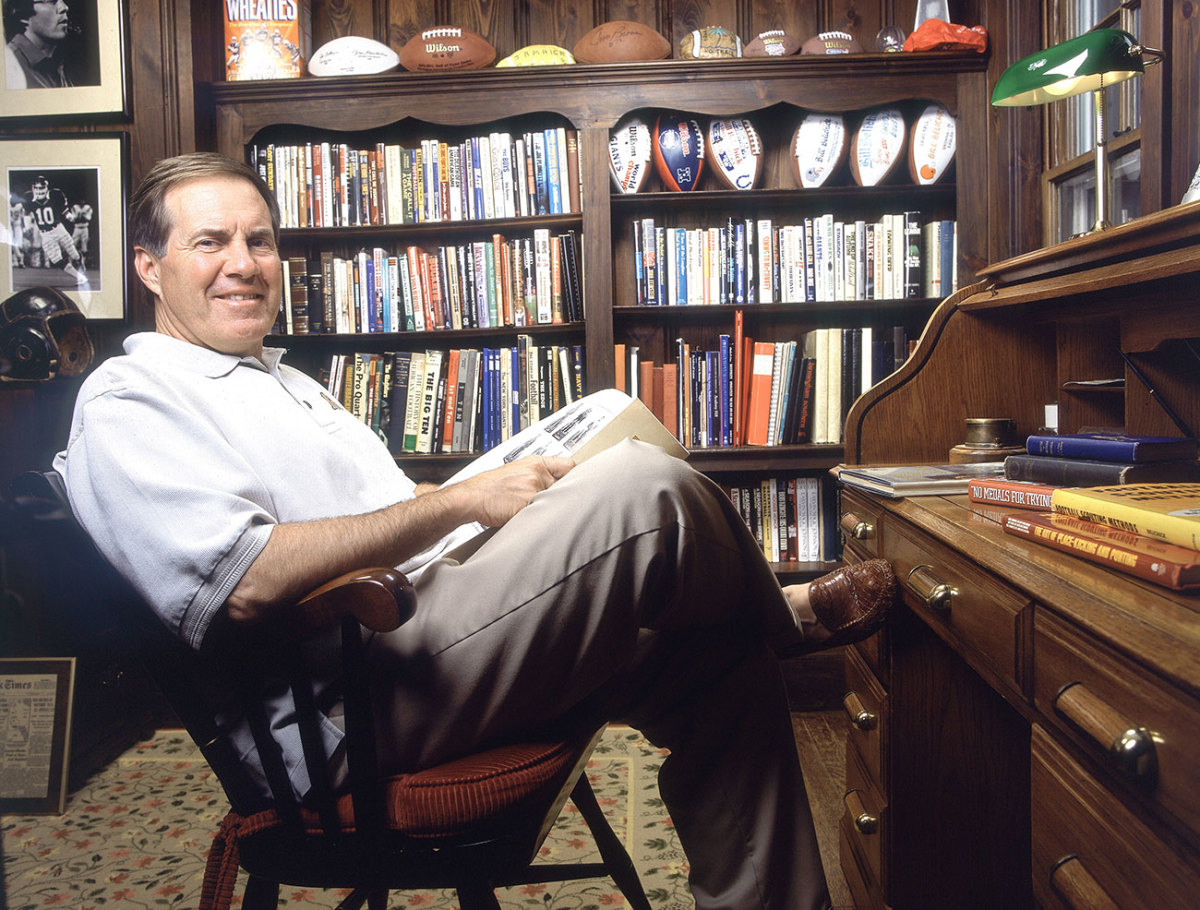

Three or four times in my life at the magazine, the boss said something to the effect of: Tell me what makes so-and-so tick. Sandwiched between Super Bowl wins two and three in the offseason of 2004, that was my assignment with Belichick.

I approached him early in the offseason, told him I was doing a profile on him and asked him if he could give me the 10 to 20 people I should definitely talk to. He spent an hour on the phone with me one night, going over stories I should pursue, people I should talk with, etc. He was great.

I went down to Maryland, and his late father, Steve, met me and showed me around Annapolis, to places that were important in young Bill’s life. He told me stories about how when Bill was 9 or 10, he’d sit in the back of the room at the Naval Academy football offices, when Steve Belichick, an assistant coach, would debrief the team with his scouting report on that week’s game. Then we went to the Belichick home, a smallish, understated blue-collar house where Steve and Jeannette raised their one child.

I said I would love to take a peek into the room Bill grew up in. Jeannette demurred, and I didn’t press things. But they both told me enough good stories that the trip was perfect. Just perfect.

After an hour or so, I was getting ready to leave. Bill’s mom turned to me and oh-so-nicely said, “Would you like to see Bill’s room?”

Why yes. Yes I would.

These are the moments you think you’ve got a pretty good gig.

The room was sort of … barren. Future Shock, by Alvin Toffler, with some other books. Some athletic stuff from his youth, but not much. That, Jeannette Belichick said, was not unusual; this was the way they lived.

On this trip, I learned why Bill Belichick was as smart as he was. His dad was the first noted football scout; he wrote a book about scouting with a forward by the great Paul Brown. His mom knew seven languages, read the New Yorker cover to cover every week, and liked when young Bill would read a book to her while she made dinner. That combination, and how deep he got into football at such a young age … pretty telling.

Oct. 18, 2004

A League of Their Own

The Patriots set the NFL’s all-time record with their 19th straight win

LINK: www.si.com/vault/2004/10/18/8188771/a-league-of-their-own

I remember spending a few days in Foxboro, and not a soul would talk about breaking a pretty august record. No NFL team in the league’s first 84 seasons had won 19 games in a row. Lips were zipped. And Bill Belichick, early in the week, fired a special-teams player with, as I wrote, “the emotional detachment of a Paulie Walnuts” because the Patriots had a lousy special-teams performance in their 18th win.

This is the way Bill Parcells handled his teams—the way Belichick witnessed the how the Giants were run in the ’80s. If you win big, there’s always something wrong; never let players get happy. If you lose big, there’s always something good; never let players wallow and think they stink. Belichick was this way for years with the Patriots. It’s why they still win. And why, probably, it has worn so much on so many veteran players. Look at Tom Brady this spring. I don’t know what really is going on, but I can imagine that, a) Brady wants a little more of a non-football life in the offseason; and b) he’s had enough of Belichick’s mind games.

Still, there’s a price to pay if you want to be great for a long, long time. And Belichick knows how to make his players pay it.

Why does this story stick out? It’s not all that long, and I feel like I’ve written many more insightful ones. But the story of why the Patriots win is encapsulated in the first five paragraphs of my story. That’s why I like this one.

Feb. 1, 2010

Big Easy Does It

The Saints pummel the Vikings in the NFC title game

LINK: www.si.com/vault/2010/02/01/105899237/big-easy-does-it

Got some great color that week, the week of the game that in so many ways led to the Saints’ Bountygate scandal. I’m disappointed, reading the story again, that I didn’t take more notice of New Orleans beating the tar out of Brett Favre, and whether there was anything about it that seemed a little excessive. That bugs me.

I did make note of “Brett Favre getting beaten like Rocky Balboa by the New Orleans defense.” But I should have done more. In my MMQB column that weekend—I did double-duty, writing this story for the magazine and a lead on the battered Favre for MMQB—I wrote more about how brutal had been the punishment Favre suffered. But I should have been more declarative about it in the magazine.

It was around this time that I had to draw lines of demarcations. When I covered big games and wrote them for both the magazine and the top of MMQB, I had to divide the material and make it as fair and interesting for both as I could. That led to some interesting decisions, but I also strived to tell separate stories as thoroughly as I could.

Nov. 1, 2010

Concussions: The hits that are changing football

LINK: www.si.com/vault/2010/11/01/106000981/concussions

God bless Ann McKee, I remember thinking as I left her lab at the Veterans Administration hospital in Bedford, Mass., a few days after a landslide October weekend about player safety in the sport of football.

Rutgers linebacker Eric LeGrand was paralyzed on a New Jersey field, followed the next day by a Lions linebacker lying motionless after a huge hit against the Giants. Three more huge hits that day—resulting a league-record day of fines—caused the NFL to show a four-minute video to every team decrying gratuitous hits. Even smart players ripped into the league. This is football! It’s for men! “The skirts need to be taken off in the NFL offices,” fumed NFLPA president Kevin Mawae.

McKee, as a neuropathologist from Boston University and a diehard Packers fan from Wisconsin, was not into the rhetoric we heard that week from so many players. She took me into her lab, showed me slides of damaged brains of deceased players, and talked clinically about what she believed was happening in the game. Football was helping kill some of these players.

One of her last sentences to me sticks with me to this day. McKee spent a couple of hours with me, showing me slides of brain tissue magnified 100 times with stained brown bits of a toxic protein. She told me she wished she could show these slides to players like James Harrison and Brandon Meriweather, heavily fined for brutal hits. When I was about to leave, I asked her what she hoped her work, and the publicity it was starting to get, would do.

“I wonder,” said this woman who spent her fall Sundays watching two or three games every week. “Can we make it more of an Indy 500 and less of a demolition derby?”

McKee, to this day, continue to collect evidence. The league continues to tweak the rules—the latest last week further criminalizing helmet hits and trying to take collisions out of kickoffs. It may be that football is simply too violent to survive. I’ve thought over the last few years that the game is fortunate to have aggressive authorites like Ann McKee, Bennet Omalu and Chris Nowinski, along with journalistic watchdogs like Ken Belson of the New York Times, and some increasingly aware (but obviously conflicted) head-trauma-conscious people inside the league office. If the game’s going to survive, knowledge must be power. And the reality of player-health knowledge, often times, can be very unpleasant.

July 22, 2013

Jason Garrett’s training camp speech to the Cowboys

LINK: www.si.com/2013/07/17/jason-garrett-dallas-cowboys-speech

This 36-minute video meant a lot to me. On the first day in the history of The MMQB we started by attempting to blow up the internet with something that hadn’t been recorded and shown in its entirety: an NFL head coach’s camp-opening address to his team. The rules, the season theme, the passion, the message.

It happened on a Saturday afternoon at the Cowboys camp in Oxnard, Calif., two miles from the shores of the Pacific, in a team meeting room at the hotel the Cowboys commandeer for their summer camp. Garrett spoke. We recorded it, agreeing to bleep out the four-letter words. On the morning of July 22, 2013, when we launched, this was our first piece of unique content. I’m proud of it to this day, because it’s not easy to get an NFL team to hand you the coach’s speech to his players so you can share it with the world.

I was on my training camp tour that summer, and one AFC coach a bit sheepishly told me he’d watched the speech, then told the coaches on his staff he wanted them to watch it. He told me he’d learned a few things from it, and he was impressed with Garrett’s passion and attention to passion. Garrett on tuning out distractions:

“Think Einstein listed to the noise?” Think Martin Luther King listened to the noise?

“Don’t listen to the noise.”

You might ask why this video is on the list. At the time, I thought it was vital that our website not just be the best writing about football; it needed to spread its wings and be different. Videos, podcasts, writing, guest columns. We needed to be a blank canvas in a new media world. This was the start.

July 23, 2013

Colin Kaepernick Does Not Care What You Think About His Tattoos

Coming off his breakout season, the 49ers QB was all about football

LINK: www.si.com/2013/07/23/colin-kaepernick-49ers

The last time I had more than a passing conversation with Colin Kaepernick was on a spring night in 2013, in the darkness, driving back from an appearance at his old high school’s graduation. Two things strike me reading the story five years later:

1. He was absolutely not a political person then, or at least did not speak as one.

2. I cannot believe he is not playing in the NFL. It seems just crazy.

Football, people. Football. Think football, not politics. In the previous postseason, Kaepernick’s 49ers averaged 34.7 points per game, and he was one goal-line completion from winning the Super Bowl against Baltimore.

A passage I wrote in that story, five months after Baltimore’s 34-31 Super Bowl victory over Kaepernick’s 49ers:

“How long,” I asked, “did it take you to get over the game?”

“Still not really over it,” he said ruefully. “It feels like something was stolen.”

But look at what was accomplished by Kaepernick last year. When Tom Brady and the Patriots fought all the way back from a 31-3 deficit to tie the game at 31 on a rainy December Sunday night in Foxboro, Kaepernick responded. He faced down a zero blitz by New England and found Michael Crabtree for the winning touchdown in a 41-31 stunner. “What a surreal moment,” he said. “It was crazy, going to shake his hand after the game, knowing we’d just beaten a guy who’s going to go down as one of the greatest ever. I can’t even remember what I said, or what he said.”

By the time the playoffs began, no one knew quite what to expect out of Kaepernick, running the crazy read-option maybe 20 or 30 percent of the time. Against Green Bay, he kept it a lot, rushing 16 times for 181 yards. The NFL had been alive for 93 seasons, and no quarterback had rushed for that many yards in a game—ever. That game made Kaepernick realize what a crazy weapon his legs can be.

“It got to a point,” Kaepernick said, “where we could hear them [the Packers] arguing while we were in our huddle, yelling at each other. ‘You’re supposed to do this,’ or ‘You have to do this, then the other.’ At that point, our offense was like, It’s over,because as soon as you start turning on your teammates, you know you’re not going to be productive … You know you have them in the palm of your hands.”

At Atlanta the next week, for the NFC title, Kaepernick ran the ball exactly once off the read-option … and got buried for a two-yard loss. His arm won that game. And it got the Niners to the Super Bowl.

This is a guy who can’t find a job in the NFL? No wonder he’s suing.

Dec. 4-6, 2013

Game 150: A Week in the Life of an Officiating Crew

An unprecedented glimpse at the third team on the field

I broke the 16,000-word opus on a game week with Gene Steratore’s crew into three parts:

The crew’s lives as real people.

Game day, Baltimore at Chicago.

I give credit to Dean Blandino for this, as I wrote the other day. When I started the site, I wanted some special things, things that hadn’t been done before. And a week in the life of an officiating crew was virgin territory. Blandino took a chance, and there was stuff in here, in restrospect, that he wishes was not. Namely, the crew members’ obsession with grades. Blandino preached in his short tenure as VP of Officiating that the officials should just worry about calling the best game they could; the grades would take care of themselves. Well, they would. But that didn’t stop Steratore and his crew from being hugely bummed out about some downgrades from their previous game.

I learned so much doing this story—truly, the most of any in my 29 years at SI and The MMQB. The officials are behind an iron curtain. So this was something we took a lot of pride in doing, and in trying to do right.

Please watch the videos by John DePetro with each piece. From Steratore’s western Pennsylvania kitchen (he makes a good red sauce, and was thoughtful enough to provide the Chianti even though he doesn’t drink alcohol during the season) to back judge Dino Paganelli’s AP history class in western Michigan, to the other members of the crew, I hope you got the feeling I got. I hope you came away thinking you now understood a little bit about the real life of an officiating crew.

Nov. 18-19, 2015

A quarterback and his game plan

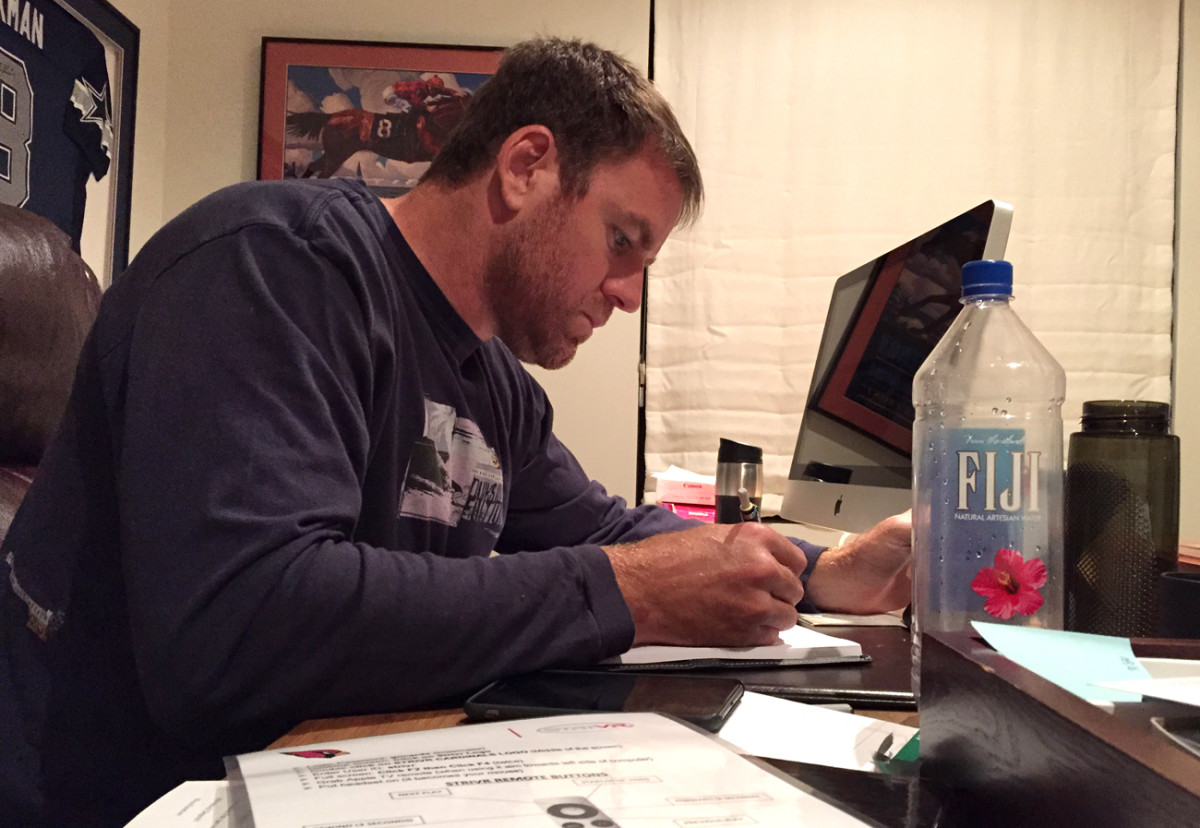

Behind the scenes with Carson Palmer as a game plan is installed

The Cards were practicing in West Virginia for a few days in October 2015, between two Eastern Time games, and I went there to try to convince Palmer to let me do something I really don’t think he wanted to do—open up his world to me for a game week to see how the life of a quarterback—particularly an anal one like him—works.

I was surprised. He really wanted to do. It was going to be a major intrusion on his life. I wanted to be with him at his home Tuesday evening when the gameplan came to him via email, I wanted to watch him prepare (including the use of a Virtual Reality headsets). I wanted to talk to him as he went back and forth to practice, to digest his days. And I needed him on Saturday, the day before the game, to explain the final prep and how deeply he studied. Palmer was perfect, and coach Bruce Arians did a great job too—even though he was really hesitant about it.

As with the officials’ story, I did this in multiple parts.

Part 1: Five days to learn 171 plays.

Part 2: Game Day in Cleveland, and what happens to the best-laid game plans.

What was cool here, and what made me feel like I got it right, was a couple of texts from Tony Romo and Josh McCown, saying, in effect, That’s exactly what we go through every game week. Right down to the improvisation, which played a huge part in this win over Cleveland, I felt like this told the real story of what a quarterback goes through if he’s doing it right.

Feb. 12, 2018

Wristband 145

Behind the play that confused the Patriots and gave the Eagles their Super Bowl LII win

LINK: www.si.com/nfl/2018/02/11/eagles-super-bowl-zach-ertz-touchdown-wristband-145-mmqb-peter-king

This lead to Monday Morning Quarterback eight days after the Super Bowl is one of the most enjoyable stories of my life. I was amazed, first, that six days after the game, the three men who invented the play that won the Super Bowl—receivers coach Mike Groh, offensive coordinator Frank Reich and coach Doug Pederson—agreed to meet me in Pederson’s office to explain how this innovative, new, never-been-run-before touchdown pass to Zach Ertz came to be. (Credit Reich. He was one of the brains behind it, but he wanted the other two in the room, and so at 9:30 on Saturday morning, all six eyes of the innovators still bleary, they all met me.)

So many interesting things about Gun trey left, open buster star motion, 383 X follow Y slant. But what will live in Super Bowl history—and in the burgeoning legacy of Pederson and his vastly underrated 2017 coaching staff—is that this play was not one of the 193 in the game plan when the Eagles left Philadelphia; it’s one of 12 that got invented in Minneapolis. It has so many tentacles that it wouldn’t have mattered how much Bill Belichick and Matt Patricia and Ernie Adams studied the Eagles. They would not have found this. This wasn’t good coaching. This was superb coaching, the kind of coaching that wins a Super Bowl.

As has happened many times in my 29 years at Sports Illustrated and The MMQB, I was so excited when I pressed the SEND button and sent this column to my editor—Dom Bonvissuto, in this case. It’s crazy to say I was filled with joy, because you’d think at 60, I wouldn’t get filled with joy over something I’ve done for so long. But that’s the great thing about this job. It still fills me with joy.

Thanks, Peter. Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.