The Family Ownership Dramas That Roil the NFL

Even in a city famous for its burial rituals, this one was notable for its scope and scale. On March 23, New Orleans came to a standstill for the mourning of Tom Benson. Radio stations offered traffic reports and alternate routes for getting to (and avoiding) Benson’s mass at St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter. Louisiana’s governor, John Bel Edwards, stood alongside business leaders as Benson, the state’s only listed billionaire, was commemorated and celebrated.

The embodiment of the self-made man, Benson, who died at 90, was the proprietor of various local enterprises, from car dealerships to banks. But he was best known for owning Louisiana’s two professional sports franchises, the NFL’s Saints and the NBA’s Pelicans. So it was that commissioners Roger Goodell and Adam Silver both attended the funeral. Pallbearers included Drew Brees and Anthony Davis, as well as their respective coaches, Sean Payton and Alvin Gentry.

There were, however, some conspicuous absences. Benson’s daughter, Renee, was not in attendance. Nor were his granddaughter and grandson, Rita and Ryan LeBlanc. The three estranged family members—the Three R’s, they’re called in New Orleans—were invited to a private viewing of Benson’s body three days before the funeral. But it was made clear they were not welcome at the funeral.

The source of the estrangement has been embedded into New Orleans lore. By most accounts the Three R’s never embraced Benson’s third wife, Gayle, whom he married in 2004. Before a Saints-Falcons game late in the ’14 season, Gayle Benson and Rita LeBlanc exchanged heated words in the owner’s suite at the Superdome. As fireworks lit up the field, the dispute turned physical, as Rita (then 38) reportedly grabbed Gayle (then 68) by the shoulders and began shaking her repeatedly as Tom looked on disgustedly.

Six days later Tom wrote a letter to Renee, Ryan and Rita that read in part: “During the 80 years of my life, I have built a rather large estate, which was intended to mainly be for you all as my family. Suddenly after I remarried you all became offensive and did not act in an appropriate manner and even had arguments among yourselves which created a very unpleasant family situation which I will not stand for.” He then banned them from Saints and Pelicans games.

For years Benson had made clear that he was leaving his empire, including the teams, to Renee, Ryan and Rita. In particular, Rita was being groomed to take over as majority owner. She had interned in the league office while at Texas A&M and joined the Saints full-time in 2001. By ’05 she had risen to executive vice president. When the following season the Saints announced their rebuilding plans post-Katrina, it was Rita—and pointedly not Tom—who stood alongside commissioner Paul Tagliabue.

But after this family dispute, Benson called a new play and named Gayle as the sole beneficiary. His last will and testament, revised and dated July 27, 2015, read in part: “I specifically provide that Renee Benson, Rita LeBlanc, Ryan LeBlanc, and all of their descendants shall have no interest in my succession whatsoever, and no legacy or other inheritance or benefit of any kind shall be paid to any of them under this will or otherwise.”

The three spurned family members filed a petition in Civil District Court in New Orleans asserting that Benson was mentally unfit to make this decision. After an out-of-court settlement (largely in the owner’s favor), Rita took out a newspaper ad asking New Orleans’ citizenry to “pray for the reunification of our family.” Nonetheless, at Tom’s death Gayle, whose business background is in interior design and real estate, became the owner of both an NFL and an NBA team—making her, by most measures, the most powerful woman in U.S. sports.

The intrigue made for gripping local theater. The public was split over which side to support. The New Orleans Advocate once referred to Benson’s change of heart—and change of succession—as “a palace coup.”

At NFL headquarters in midtown Manhattan, the Benson feud was no idle matter. Family disputes, embroidered with Shakespearean elements, have always been a part of the league’s history. But as the values of teams—and the age of their patriarch owners—drift ever higher, lines of succession become more and more significant. Add in the complexities brought on by second (and third) spouses, stepchildren and the specter of a hefty inheritance tax, and it’s a volatile mix that can disrupt—and subvert—a league.

One former longtime high-ranking NFL executive puts it this way: “Trust me, the same way the public talks about head injuries or Colin Kaepernick, [the league office] talks about these ownership issues. It can be hugely destabilizing. Just look at Carolina.”

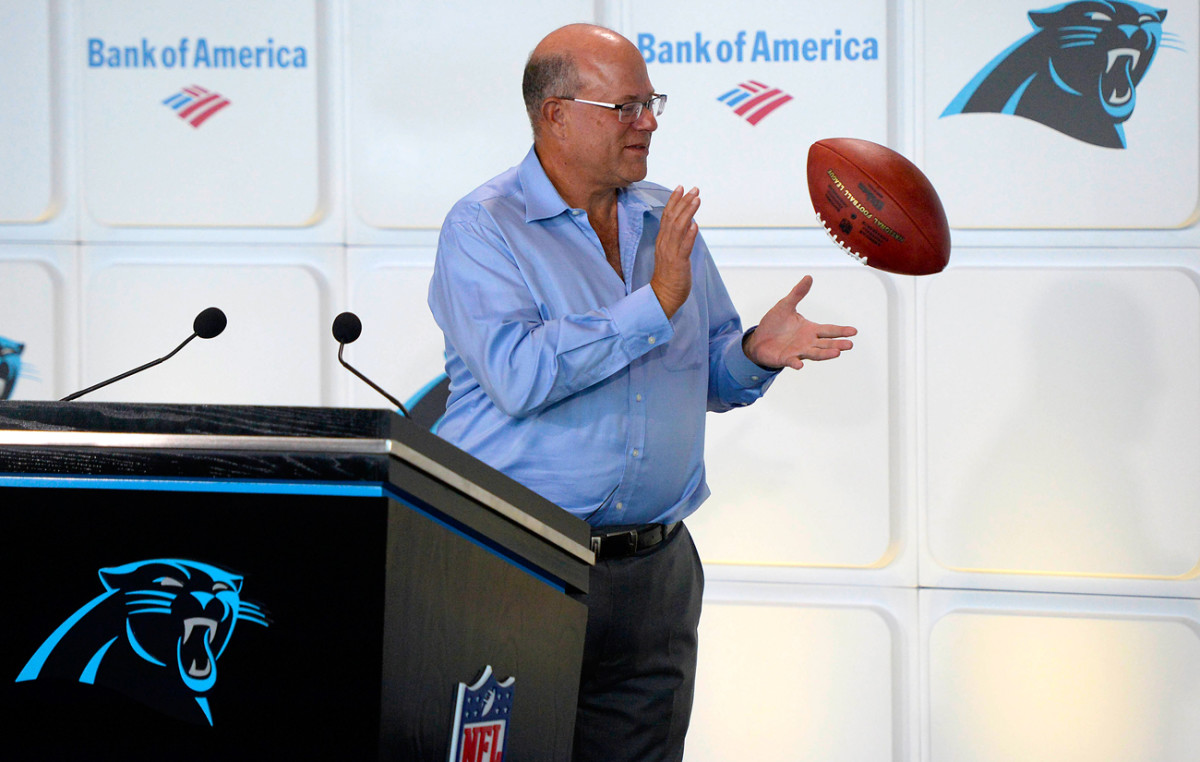

When Jerry Richardson led a group to buy the expansion Panthers in 1993, it was assumed that his two sons, Mark and Jon, would eventually take over the team. For years Mark was the team president, representing the franchise at owners meetings and serving on the league’s influential competition committee, while Jon ran the team’s venue, Bank of America Stadium.

The Definitive Guide to Each and Every NFL Owner

Richardson’s sons, however, were often at odds with each other. Eventually, sources tell SI, their father had enough of their feuding. On Sept. 1, 2009, the team made the abrupt announcement that both Mark and Jon were resigning from their jobs and offered no further explanation. Even before Jon died in 2013, Jerry asserted that he would sell the franchise rather than leave it to his sons.

On Dec. 17, 2017, Sports Illustrated published a story in which multiple former and current Panthers employees accused Richardson of sexual harassment, of using racial epithets and of then effectively buying their silence with non-disclosure agreements. That same evening Richardson issued a press release stating that he was selling the team. Buyers emerged offering more than $2 billion, and with them came with uncertainty, including whether the Panthers would remain in Charlotte. In mid-May, hedge fund manager David Tepper won the derby, reportedly for $2.275 billion, and announced that the team would not relocate. But the concern would have been avoided had Richardson left the Panthers to his heirs.

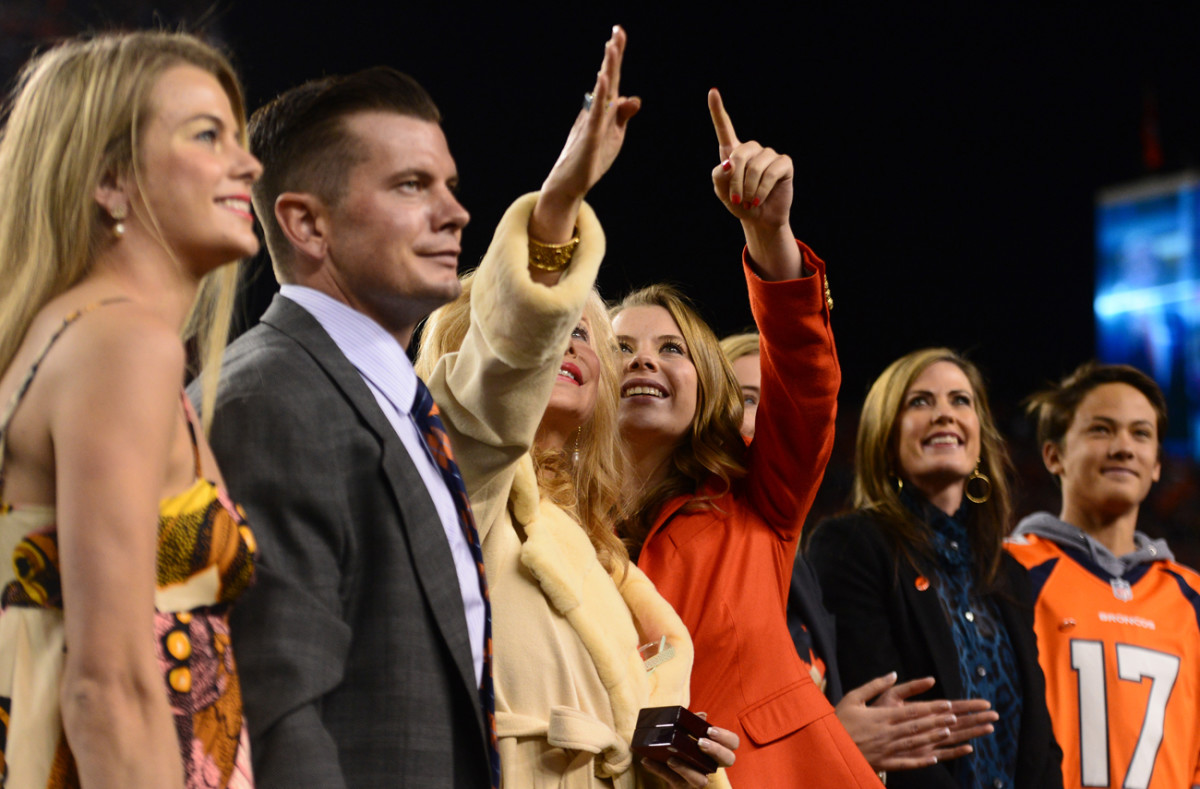

Another succession scenario is playing out in Denver. Before his health began to fail him, longtime Broncos owner Pat Bowlen expressed his unwavering intention to keep the franchise in the family, with each of his seven children receiving an equal share upon his death. But that didn’t settle who would actually run the Broncos. In 2014, Bowlen, suffering from Alzheimer’s, relinquished control, ceding day-to-day operations to CEO Joe Ellis—who as a nephew of George H.W. Bush is familiar with thorny issues around family lineage. Bowlen put the team in a trust and laid out a a plan to determine which child was the most capable successor. Ellis, team counsel Rich Slivka and Denver lawyer Mary Kelly, who specializes in family law and mediation, will make the determination.

According to The Denver Post, Bowlen’s plan refers to such abstract qualities as “leadership,” “integrity” and “sound judgment” in deciding his potential successor. It also includes specific requirements, such as an MBA, J.D. or other advanced business-related degree, and mandates at least five years of senior management experience with the league, a team or a stadium, though it does not specify which job titles are considered “senior management.” While such a checklist makes sense, one can imagine how this kind of bake-off could cause rifts among jockeying siblings.

In late May the second-oldest child, Beth Bowlen, made her case to The Athletic. After recently earning her law degree from the University of Denver, Beth, now 47, noted, “I have completed the criteria laid out by the trustees.” Reached for comment by the Denver media, the trust responded tersely: “The trustees have informed Beth of their determination that she is not capable or qualified at this time. We will continue to follow Pat Bowlen’s long-standing succession plan for the future ownership of the Denver Broncos.”

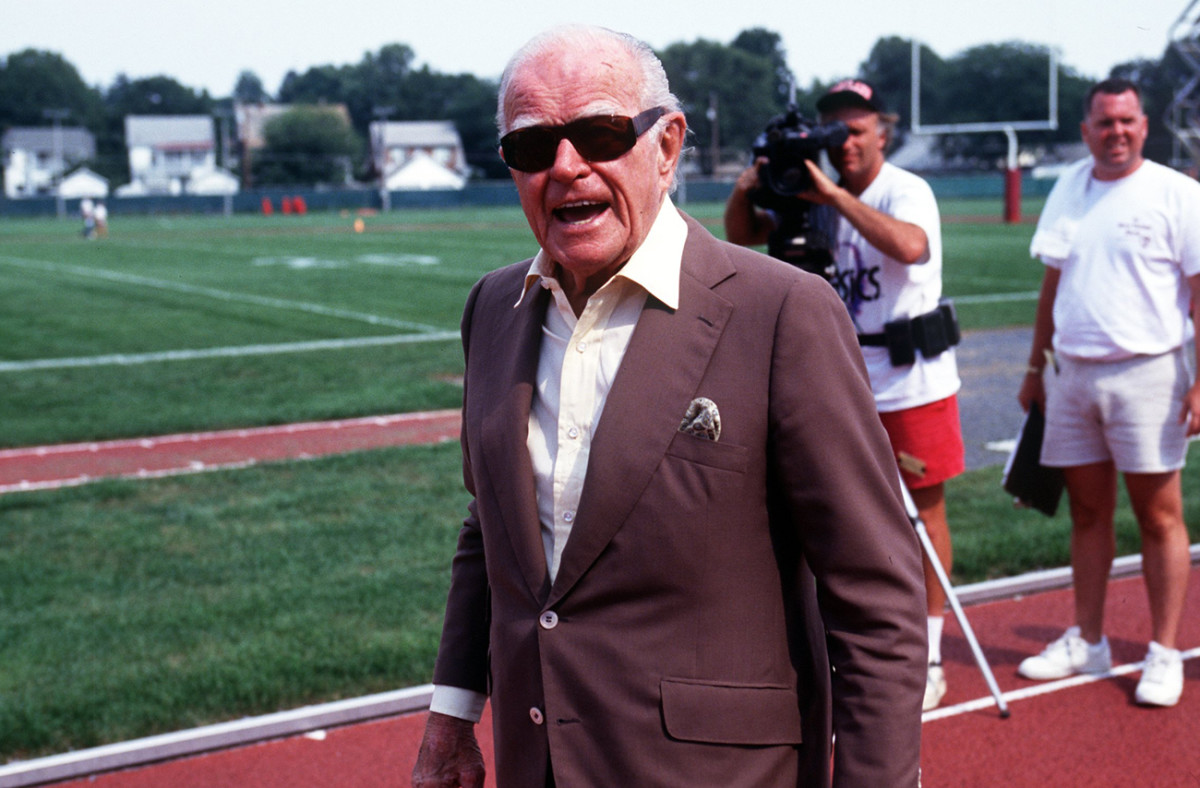

In Chicago, Virginia McCaskey, the 95-year-old daughter of Bears founder and patriarch George Halas, stands as principal owner, controlling 80% of the team. McCaskey is still a vital presence. Earlier this year she declared herself “pissed off” by the Bears’ 5–11 finish in 2017. Until recently she drove herself in a Cadillac adorned with a bumper sticker reading PRAY THE ROSARY. But for all her vim and vinegar, the Bears’ succession plan is uncertain.

When Virginia took over upon her father’s death in 1983, it gave rise to an unusual situation. For all the scions eager to seize control—Jerry Jones Jr., for instance, allegedly hands out business cards declaring himself “future owner” of the Dallas Cowboys—McCaskey had to prevail on some of her then 11 children to join the family business. Perhaps most notably, Michael McCaskey served, somewhat reluctantly, as Bears president and CEO, surely one of the few NFL executives to hold a Ph.D (in business from Case Western).

In 1999, after the botched hiring of a head coach, Virginia moved Michael to chairman of the board. In 2011 he left the team to pursue his passion for photography. Jeff Davis, a Chicago journalist and author of Papa Bear: The Life and Legacy of George Halas, reached this conclusion: “The McCaskeys are not bad people. It’s unfair to say that. They are good people. But they’re not very hip, and they were not ever supposed to run the Bears.’’

Even owners anticipating succession problems haven’t been immune to conflict and chaos. Before his death in 2013, Titans owner Bud Adams bequeathed the family business, including the team, via a holding company, to his three children—Susie, Amy and Kenneth—and their families. Adams drew up bylaws that included a three-quarter “supermajority” voting requirement on crucial issues, effectively preventing the families of two siblings from ganging up on a third.

The NFL fined the Titans over this three-fourths standard, claiming that the structure violated league bylaws, but it remains unchanged. Not that it has prevented the siblings from feuding. In the 1990s, Tommy Smith, Susie’s husband, served as CEO before Adams made the awkward move of firing his son-in-law. After Adams’ death, Smith re-emerged as the Titans’ president and CEO. But in 2015, he was out again. Smith cited the demands of his other business considerations, but The Tennessean suggested the move reflected “an apparent shift in thinking within the family-owned business.”

Last year Susie Adams announced that she was putting up for sale her share of the holding company that includes the franchise. Buyers have been hard to come by—perhaps not surprising, given that the one-third share, which would amount to nearly $700 million based on Forbes’s valuation of the team at $2.05 billion—comes with no path to full ownership in the Titans, no guaranteed seat on the board and the three-fourths majority clause that creates blocking rights but that prevents meaningful change without consensus among the owners.

Vaulting ambitions, shifting allegiances, dynastic dreams, clans severed by mistrust and distrust, unclear succession plans, filial fights . . . from Henry Ford’s auto company to the Bluths’ banana stands, these are elements common to the family-owned business, a cornerstone of the American economy. Depending on which study you cite, as many as 90% of all U.S. enterprise is family-owned. And even when companies are publically traded, families often still hold considerable power—as shareholders of, say, Walmart are likely aware.

Family businesses can be immensely successful and immensely gratifying, an opportunity for a clan to work together and build generational wealth. They can also be immensely fraught, marrying the stress of family life with that of the workplace life. A study commissioned by J.P. Morgan Private Bank revealed that more than half of all family business leaders expect to transfer ownership to the next generation. But in reality only one-third of businesses make such a transition; the rest are either sold or dissolved. As The Economist once put it, “Family firms are frequently more riven with intrigue and visceral hatreds than a medieval court—and for similar reasons.”

Jerry Richardson's Hubris Remains Immortalized in His Statue

In many ways the family-owned sports franchise is not manifestly different from, say, the family-owned plumbing supply business or catering hall. “The reality is that in order to have a healthy and smooth-running organization, what you really need to do is build a healthy, functioning family,” says Joe Astrachan, Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship at Cornell’s SC Johnson College of Business and a family business expert. “That’s true whether it’s a family restaurant or a football team.”

Yet in other ways, a professional sports franchise is altogether different. Perhaps most obviously, there’s the staggering value and appreciation. Never mind that George Halas paid $100 for the Chicago Bears in 1920, the Pittsburgh Steelers were purchased for $2,500 in 1933 or that the eight original AFL owners, including Bud Adams, acquired their franchises for $25,000. Even in recent years, owners have made, literally, a fortune. For instance, in 2005 Ziggy Wilf joined five partners and bought the Minnesota Vikings for a reported $600 million. If the Panthers—playing in a smaller media market, and in a lesser venue—are worth $2.3 billion, the Vikings could be worth as much as $3 billion, a five-fold increase in value in a little over a decade. Jerry Jones bought the Dallas Cowboys in 1989 for $140 million, the first nine-figure purchase of a sports team. Risky proposition? The Cowboys are now worth an estimated $4.2 billion.

“Say the local family furniture store is not worth very much. So if there are three kids [it’s likely] one of them works in the furniture store and the other two went off and became lawyers and doctors. It just is not that much to fight over,” says Wayne Rivers, co-founder and president of the Raleigh-based Family Business Institute. “But when you’re talking about a team worth a couple billion dollars, well, lawyer up!”

Apart from wealth, owning a professional sports team confers a measure of celebrity. To some, ownerships represents a trophy and fame represents a perk. To others, it’s an annoyance. But unlike other family-run businesses, owners are public figures. “I would say the visibility is having the biggest effect,” says Astrachan. “The pressure on a sports family is much greater than most other businesses. The media are constantly covering their business. And because of that, they’re far more visible. They get far more comments from the public than a normal family business, even of a similar size and value. . . . If the idea is, You know what, we’re going to clamp down on you so hard because we don’t want you to embarrass us, we’re not going to explain why, you’re not going to be in on what’s going on, then you can have all kinds of dysfunction.”

While there are family feuds in most sports—one recent example: Jeanie Buss fired her brother as she seized control over the Lakers—they are especially pronounced in the NFL. The league bans corporate ownership, so wealthy individuals or families are, effectively, the only option.

The NFL is also the league with the highest percentage of franchise revenues—roughly 80%—coming from leaguewide sharing outside the local market. What this means is that even a poorly run franchise is assured of making great sums of money, reducing pressure for profitability and cash flow.

For Many NFL Players, Summer Doesn't Bring Much of a Break

And although (because?) there are only eight home games per season in the NFL, more so than in other leagues the owners are demi-celebrities, held up as custodians of a civic trust, expected to sit alongside their clan in a luxury suite. As Colts owner Jim Irsay—who inherited the team from his father and plans to leave it his to offspring—explained to SI in 2009, “If I’m not there on game day, people will notice, and I’ll have to answer for that.”

One NFL source points out that “family drama at the team level” has always been a challenge, ticking off several examples from decades past. In the 1990s, Eddie DeBartolo Jr., owner of the dynastic San Francisco 49ers, became embroiled in a gambling extortion scandal and eventually pleaded guilty in federal court to failure to report a felony.

In the wake of the scandal, he and his sister, Denise DeBartolo York, sued and countersued each other. To put it charitably, a rift still exists between Eddie and the York family—Denise’s husband, John, in particular. (The 49ers’ CEO and effective owner, Jed York, is Denise’s son and Eddie’s nephew.)

When Falcons owner Rankin Smith made rumblings that he was selling the team, a child he had fathered out of wedlock emerged, demanding a share. In 2002, Taylor Smith sold the team his father had bought in 1965 for $8.5 million to Arthur Blank for $545 million. In 2013, Blank’s second wife, Stephanie, served him with divorce papers during Super Bowl XLVII, temporarily clouding the Falcons’ ownership picture.

In Washington, it was assumed that longtime Redskins owner Jack Kent Cooke would leave the team to his children upon his death; his son, John Kent Cooke, was the Redskins’ longtime president and presumed heir. Jack had declared in 1992, “When I’m gone, someone named Cooke is going to run this team. And when he’s gone someone else named Cooke is going to run this team.” But Jack Kent also, memorably, declared, “I don’t intend to die.” He did, in 1997, but not before changing his will seven times in the last 10 years of his life. In the final draft, he’d left the Redskins not to his offspring, but to a trust, with instructions to sell it, the proceeds going to the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. So it was that John Kent Cooke put together a $750 million bid to buy the team that his father had owned and for which he had worked for decades. Yet the trustees were duty-bound to accept to best price; and Dan Snyder paid $800 million for the team and the stadium, then the largest sports transaction in history.

Further complicating matters in many cases: the specter of the estate tax. While most NFL owners are thrilled by ever-increasing franchise valuations, it inspires concern among some owners, especially those whose net worth is concentrated mostly in the team. Under current federal laws, estates in excess of $11.18 million are subject to a 40 percent tax before assets are transferred to heirs. Everything above the basis—the original acquisition cost—is taxable at death.

A cautionary tale comes in the form of Joe Robbie, former owner the Miami Dolphins. Robbie passed away in January 1990. The bulk of his net worth was tied up in the Dolphins, and he had not been proficient in his estate planning. Beset by internal feuding, the Robbie family was forced to sell the franchise at a deeply discounted price in order to pay the reported $47 million in estate taxes. While it’s safe to assume that most NFL families have undertaken estate and wealth transfer planning to avoid such scenarios, the estate tax still looms large. When in 2015 the NFL allowed trust ownership of teams and dropped the percentage that owners are required to control to as low as five percent, it was seen as an effort to keep teams in families. (Reportedly, 31 of the 32 teams approved this change with, ironically, only Tennessee abstaining.)

A source with firsthand knowledge of the NFL tells SI that in part to combat “the Beverly Hillbillies scenario,” the NFL keeps close ties with a group of billionaires, who could—and would—potentially buy a team. Steeped in finance backgrounds, they would, presumably, run teams with professionalism, emotional detachment and sophistication, unencumbered by family drama and melodrama. They would buy a team to diversify existing wealth rather than to create new wealth. According to the source, the league’s thinking goes like this: The 32 NFL franchises should be run like the multibillion-dollar assets they are; not like multimillion-dollar assets they were.

Inside NFL headquarters, the names on the list of potential owners are referred to as “Tiger cubs.” Roger Goodell’s brother, Bill, was a longtime general counsel at Tiger Management, a successful New York hedge fund, where his colleagues included men with the means and interest to own an NFL team. It has not gone unnoticed that the NBA has made a recent practice of seeing to it that when longtime owners are ready (or forced) to sell—Herb Kohl in Milwaukee, Donald Sterling with the Clippers—the buyers have been billionaires from out of state who made their fortunes outside of sports. The eventual buyer of the Panthers, David Tepper, is a hedge-fund billionaire (net worth $11 billion) from Pittsburgh who was well-known to the league as a minority owner of the Steelers. (The NFL did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.)

For all the family drama—and the instability it creates—the NFL is unlikely to relax its ban on corporate ownership, the Green Bay Packers’ unique structure notwithstanding. In 1996, NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue and then vice president of football development Roger Goodell took meetings with Disney representatives to discuss the possibility of financing a franchise in Los Angeles. But it never happened. And likely never will.

Richard Sherman and the Cornerback Summit

Like Winston Churchill’s line about democracy, single-family ownership is perhaps the worst model for the NFL ownership—except for all the others. A publically traded company, which owes a duty to shareholders, tends to be motivated by short-term profit. The board of a publically traded company is unable to make quick decisions the way individual owners can. Managers of public companies—with an eye on their next career move—are prone to seek short-term wins over long-term growth. And when new management teams come, they bring new philosophies; and this whipsawing strategy is at odds with stability.

“If you’re going to make a sports analogy to non-family management, [public companies] are always looking to hit a home run or throw a bomb,” says Astrachan, “whereas family businesses are a ground game. Not a lot of the debt, not a lot of the showmanship, but we’re going to slog through this and make this work, and we’re going to build a stable base, which allows you to have that dynastic quality.”

Astrachan sits on the boards of multiple family businesses and consults for Fortune 500 firms. His unsolicited advice for the NFL for finding stability amid its feuding clans: “I would be providing educational quasi-consultative services to the offspring of these families—regardless of whether or not the patriarch thought it was too intrusive.”

Rivers, of the Family Business Institute, agrees. And he adds that, given the red-hot sports economy, there’s no time like this present. “The seeds of family business destruction are sown in good times . . . in good times, family businesses become complacent. They start to read their own press clippings. They are making more money than they ever have before. They start to believe in their own legend. That is when they get in trouble and get sloppy and make mistakes. That’s when the family intrigue can come out, because they bicker over money and power. It can be a pretty heady, exciting environment; but also a toxic environment if they are not careful.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.