The History of Brees, Before He Makes History Again

Zach Strief’s first impression of Drew Brees was that he couldn’t throw the ball 20 yards. This was the spring of 2006, and both players were new to New Orleans—Strief had just been drafted in the seventh round, while Brees was the high-risk free-agent signing at quarterback, just a few months removed from a complicated surgery to repair his throwing shoulder.

Brees’s right arm was still fledgling for months—on the practice field, and even as late as the fourth preseason game. Strief recounts Brees attempting a mid-range out route in that final exhibition contest, just days before the season opener. The then-backup lineman felt like it took about six seconds for the ball to get to its destination; however long it took, it was an eternity for an NFL throw.

“And it was like, ‘I don’t know…’ Coach Payton has told stories about [thinking], Is this really all that he can do?” says Strief, Brees’s longtime blocker. “When you think about coming from that place, and that 13 seasons later, he’s about to do something that no player has ever done in the history of football...”

Brees, 39, is just 200 yards from the NFL’s career passing yards record, which he is likely to break next week on Monday Night Football against Washington, at home in New Orleans. David Baker, president of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, will be on the sidelines, ready to accept and deliver to Canton the football used to make the throw that breaks Peyton Manning’s mark of 71,940 passing yards. And to think, 12 years ago there was a question of whether or not Brees should throw another NFL pass.

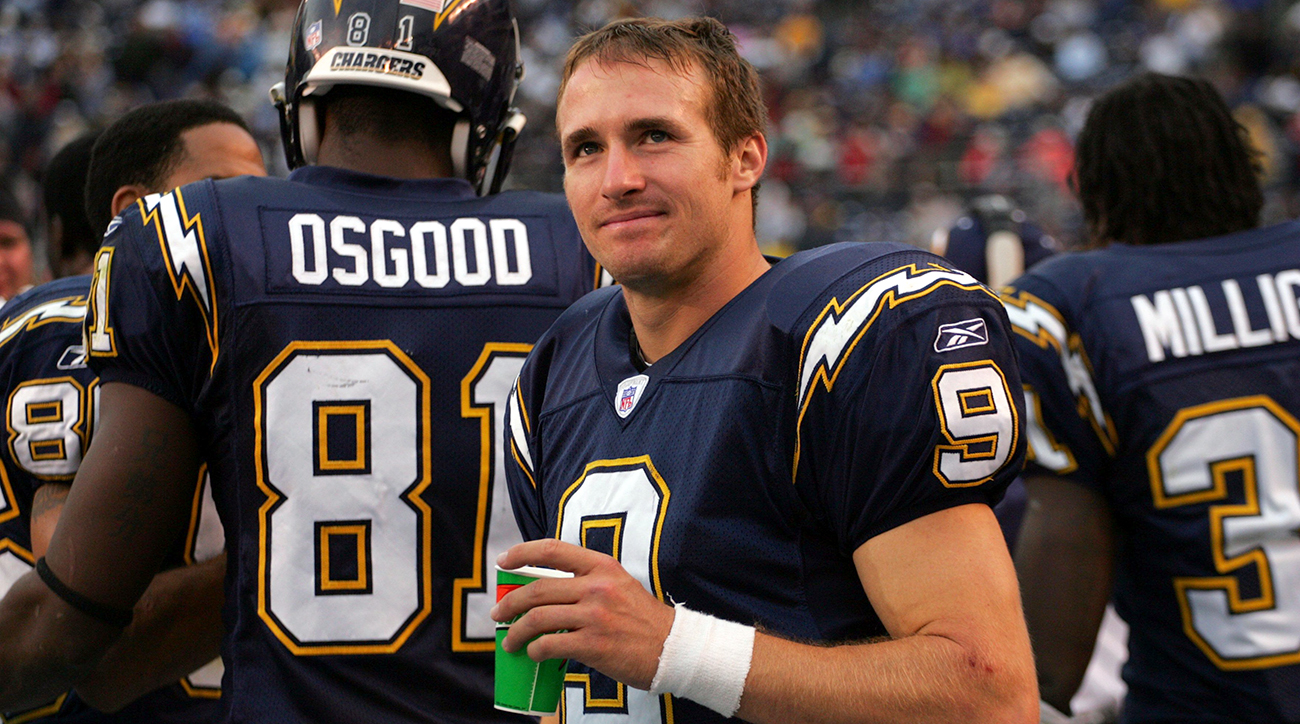

Brees’s fifth NFL season and final one in San Diego, in 2005, ended when he was diving for a fumble and a defensive tackle landed on his right shoulder. He’d already taken his share of lumps—he’d been benched multiple times, struggling so badly in 2003 that the Chargers drafted Philip Rivers that spring, and Brees was named Comeback Player of the Year in 2004 despite not having suffered an injury the previous year, customary for the recipient of that honor. With Rivers in waiting, things were really up in the air when Brees’s shoulder popped out of its socket, fully tearing the labrum and partially tearing his rotator cuff.

The Chargers moved on from him. One of his suitors in free agency, the Dolphins, flunked him on his physical. The Saints, however, decided the risk was worth it, marrying Brees and new head coach Sean Payton in the hopes of reviving a franchise that hadn’t won much, in a city still reeling from Hurricane Katrina.

It all started with another throw etched into Strief’s memory, this one in the regular-season opener of the 2006 season. Brees connected with Marques Colston on a back-shoulder toss; for the first time since his shoulder surgery, the quarterback looked confident letting it loose. The rest is, quite literally, NFL history.

In 2001, when Brees was a rookie second-round pick in San Diego, the team’s second preseason game—and the first of Brees’s career—was at Miami. A favorite story he has told through his 18-year career is the awe he felt looking up at Dan Marino’s name and career feats hanging in the stadium’s ring of honor.

“You look at the numbers and you say, ‘How long do you have to play in order to achieve that?’ ” Brees said on Sunday, after drawing closer to the mark with his 217 passing yards against the Giants. “As a kid growing up, watching guys like Marino, Montana and Elway and others, those were the guys. To be in the stadium in my very first preseason game, taking it all in, looking around at the ring of honor, and there’s his name. He’s basically the benchmark. At the time, I was just hoping to maybe become a starter some day.”

Four quarterbacks have since eclipsed Marino’s 61,361 career passing yards: Manning, Brett Favre, Brees and Tom Brady. It’s a pass-happy league today, but Brees has become the new benchmark. There have been nine 5,000-yard seasons in NFL history; Brees is responsible for five of them. He has three of the top four season completion percentages (each over 70 percent) and broke Brett Favre’s record of 6,300 completed passes earlier this season. Johnny Unitas’s mark of 47 consecutive games with a TD pass stood for more than a half-century, until Brees surpassed it in 2012.

The Roughing the Passer Rule and Football’s Unfixable Problem

Brees and Payton have been a perfect match, “co-offensive coordinators,” as Saints receiver Ted Ginn, Jr. puts it. Teammates describe the two of them as being in their own little world during the pre-practice walk-throughs, adjusting receiver splits and motions and discussing ways to pull a safety down in a certain coverage, while everyone else stands around waiting to get on with practice. Tight end Ben Watson recalls working out in the weight room, and looking through the glass windows to the indoor fieldhouse where Brees was on the field by himself going through his reads and progressions. Each week’s game plan, Brees says, is “completely different” than the last, pulling a new set of calls, shifts and formations to stay one step ahead of defenses.

There’s both a physical and mental fortitude required to achieve these feats in a league where opponents are intent on identifying and attacking your every weakness. Tom Brady’s TB12 clean eating and pliability regimen is infamous, but like the Patriots QB, Brees also believes he could play until age 45—though he thinks he’ll choose to retire before then. “If there’s another QB outworking Drew Brees,” says former teammate Adrian Peterson, “I need to see what they are doing. Because being around him and seeing the work that he put in, I know most other QBs are not doing that on a daily basis.”

Despite his accomplishments, Brees has never been named a league MVP. In 2009, the Saints’ Super Bowl season, he received 7.5 of the 50 MVP votes. In 2011, when he broke Marino’s single-season passing record with 5,476 yards (also on Monday Night Football) he received two votes.

“I 100 percent think he’s underappreciated,” says Strief, who retired earlier this year after 12 seasons with the Saints. “He’s kind of stuck in that world of—and I even hate to use the word—that it’s a system, that he’s in this place where they let him throw the ball every play, and if he was in another place it wouldn’t happen. This is what I know: All the QBs in the NFL go on the field, and they play against professional players, and try and complete every pass they throw. And nobody in the history of football has done that better than Drew Brees.”

He remains so prolific that the Hall of Fame sent a curator to last week’s game against the Giants. It seemed unlikely Brees would throw for the necessary 417 yards, but you can understand why the Hall wanted to be there just in case. After all, when you consider how he was floating passes with a bum shoulder that first summer in New Orleans, everything that’s happened since seems unlikely in retrospect, and even more remarkable.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.