Zach Miller: The Horrific Injury and the Run to Recovery

LAKE FOREST, Ill. — Zach Miller takes a deep breath. I need to see how this goes.

He’s not alone in the Chicago Bears’ indoor facility; a few members of the front office are also there, checking on other rehabbing players. When Miller announces his intention, they cover their eyes or turn away, giving him some privacy for this test. Miller takes off.

He runs at a steady, even pace. After 50 yards, he slows to a walk. His face is somewhere between a smile and a grimace, reflecting the joy at passing a milestone once seemingly out of reach, and the physical pain he had to endure while performing the simplest of athletic tasks. It wasn’t pretty, but the significance of the moment isn’t lost on those who were pretending not to watch.

In a game at New Orleans last October, Miller made a reaching, over-the-shoulder catch in the end zone for what looked like a touchdown (after review, officials ruled he did not maintain possession). As he landed his left leg bent at a sickly angle; he dislocated his knee and severed his popliteal artery. He was rushed into emergency vascular surgery for what turned out to be the first of a series of surgeries that would save his leg, which was terrifyingly close to requiring amputation. He was confined to bed rest while a device called an external fixator held his knee still and stabilized it through eight more surgeries over six weeks.

By mid-October this year, the Bears’ medical staff hadn’t officially cleared him to run, but Miller has never been one to take things slowly. Nearly a full year since that play in New Orleans, he had accomplished the feat of running again.

Miller, now 34, became a free agent in March; Chicago signed him to a one-year contract in June. His age and the severity of his injury make it unlikely that he’ll play again, let alone return during the 2018 season. But Miller has found a new role—part scout, part coach, part mentor and part inspiration—for the NFC North-leading Bears.

After his run, Miller was so happy that he couldn’t keep the secret to himself. Starting quarterback Mitchell Trubisky got a video from Miller in a group text, tapped it, and was amazed to see his teammate running. In the locker room that afternoon, center Cody Whitehair ran into a still breathless Miller, who broke the news of his achievement. “You could just tell [what had happened] by the huge smile on his face,” says Whitehair.

Within a few hours, most of Halas Hall knew about Miller’s run. “I heard just a couple minutes after he finished,” says third-string quarterback Tyler Bray. “He was ecstatic.”

The admiration of his teammates has been earned a few different ways. When Miller isn’t rehabbing, he spends several hours every Wednesday, Thursday and Friday putting together video cut-ups for the tight ends. Miller has battled injuries for much of his NFL career, which began in Jacksonville in 2009, but when he was healthy, he was one of Chicago's most consistent players. “He's been around the game a long time,” says tight end Dion Sims. “[His film work] is just something extra to give us that extra edge. That's another reason why he's around, he is always finding something to help us be better as a team.”

In Miller’s cut-ups, he breaks down individual players from the upcoming opponent’s defense. He presents his notes to the group on Saturdays before the game, and sends a long text to the group chat that sums up his notes. It took him a couple weeks to master the process of finding and pulling specific plays from folders containing hundreds of video clips, but now he has the operation down. During the week of the New England game, Miller pointed out that the Patriots were going to try to disrupt Chicago’s routes and timing with second-level releases, so he focused his cut-up specifically on New England’s linebackers and safeties.

“We have to kick him out sometimes, because we have meetings and he’s in our room cutting up film,” says tight end Trey Burton. “When we come back in we have to say, ‘Get out of here, go somewhere else.’”

On Monday afternoons, Miller meets one-on-one with head coach Matt Nagy, who actively tries to keep him involved with the team. Nagy recognizes Miller’s standing among teammates and leans on him to get a better sense of the locker room from a player’s perspective. “We talk about how we feel we are as a group, the vibe of how we're moving forward and where we are at, how guys are responding,” Miller says. After back-to-back losses to the Dolphins and Patriots that put Chicago at 3-3 earlier this season, Miller said the meetings with Nagy were especially important, because both knew the season was at a juncture—if they didn’t rebound, they were at risk of the season getting away.

It’s not common for players with long-term or season-ending injuries to travel with the team, but Miller has been on the sideline for every Bears road game this season. He is the only injured Bears player who has traveled with the team to every away game this season, and there’s good reason for it.

During a Week 9 win in Buffalo, Trubisky tried to connect with Trey Burton but sailed the pass—describing it simply as “off-target” would be charitable—for an easy interception. Despite a 31-3 lead, Trubisky aggressively unsnapped his helmet strap and slapped his hands together in frustration as he walked off the field. He took a seat on the bench and shook his head as he reviewed photos of the play on a tablet. Miller approached from the far side of the bench, where the tight ends were congregated, and took a seat right next to Trubisky. Dude, forget about it. Are you kidding me? We’re smoking them right now and you’re doing your job. Just go out there and make plays like you always do. Trubisky nodded and relaxed.

Miller took Trubisky under his wing last year when Trubisky was a 23-year-old rookie thrown into the fire as the starter in Week 5. Since then, Miller has had a way of reading Trubisky’s body language and sensing exactly when the 24-year-old signal-caller needs an intervention. “I can just tell where he’s at,” Miller says. “He’s very critical of himself and puts a lot of pressure on himself. I’m there to just tell him, Hey that’s done, it’s time to move on.”

“Anytime it doesn’t look good, he immediately comes over and it’s like a calming presence,” Trubisky says. “He tells me exactly how it is . . . I forget about what happened and I try to make more good plays.”

Bears coaches are appreciative of The Miller Effect. “He is a tremendous asset,” says quarterbacks coach Dave Ragone, who likes to refer to Miller as an honorary quarterback. “I know he has been great for Mitchell as a player.”

“It always seems to happen when it’s needed, and it might not even be something that anyone else sees,” says tight ends coach Kevin Gilbride. “It might not be an interception, it might be the second three-and-out. Other people might not feel that Mitchell needs it, but something inside is telling Zach that he does.”

Trubisky has improved in his first year under Nagy, but he still struggles with consistency and misses too many open throws. He’s sworn off social media for the season, avoiding the criticism directed at him, but the expectations are high for the No. 2 pick of the 2017 draft. The sophomore season is crucial for a quarterback’s development, which makes Miller’s steadying influence even more important. Miller even dresses to support his quarterback. When Chicago hosted the Seahawks on Monday Night Football back in Week 2, Miller sported a shirt that said MITCH PLEASE in block orange letters. “It's like a big brother, little brother type thing,” says backup quarterback Chase Daniel.

“He's looked after me ever since I got here,” Trubisky says. “I'm the oldest of four, so I don't have an older brother. I definitely look at him as an older brother and someone I can talk to at any time about anything.”

Both Miller and Trubisky describe each other with the same three words: “That’s my guy.” The two share the same barber, and they’ll frequently have “haircut nights” where they gather at one of their houses, order in food, watch TV and get haircuts. Miller will pop in Ragone’s quarterback meetings throughout the week to mess with the guys and sometimes even on Saturday nights before the game to check in on Trubisky’s pre-game mindset. “I sat in on their meeting before the Jets game, and he was just dialed in,” Miller says. “The stuff that you have to go through mentally, physically, for me to sit there and watch that, I'm just proud of how he soaks it all in.”

In March, Miller’s contract will expire. If he’s in any shape to play, the Bears will likely offer him another one-year deal on the veteran’s minimum. The Bears don’t expect anything from Miller, who was likely approaching the end of his career anyways. But Miller has never viewed this as a career-ending injury.

He has been battling uphill since he walked on as a quarterback at Nebraska as a freshman, after playing just one year of high school football. Buried on the depth chart, he transferred to Division II Nebraska-Omaha and found success. Miller never played a snap a tight end until the Division II All-Star game, but knew he’d need to switch positions if he wanted to keep playing football. The Jaguars drafted him in the sixth round in 2009, and he’s lasted nearly a decade in the league. This is just another challenge, something to fuel him as he attacks his rehab.

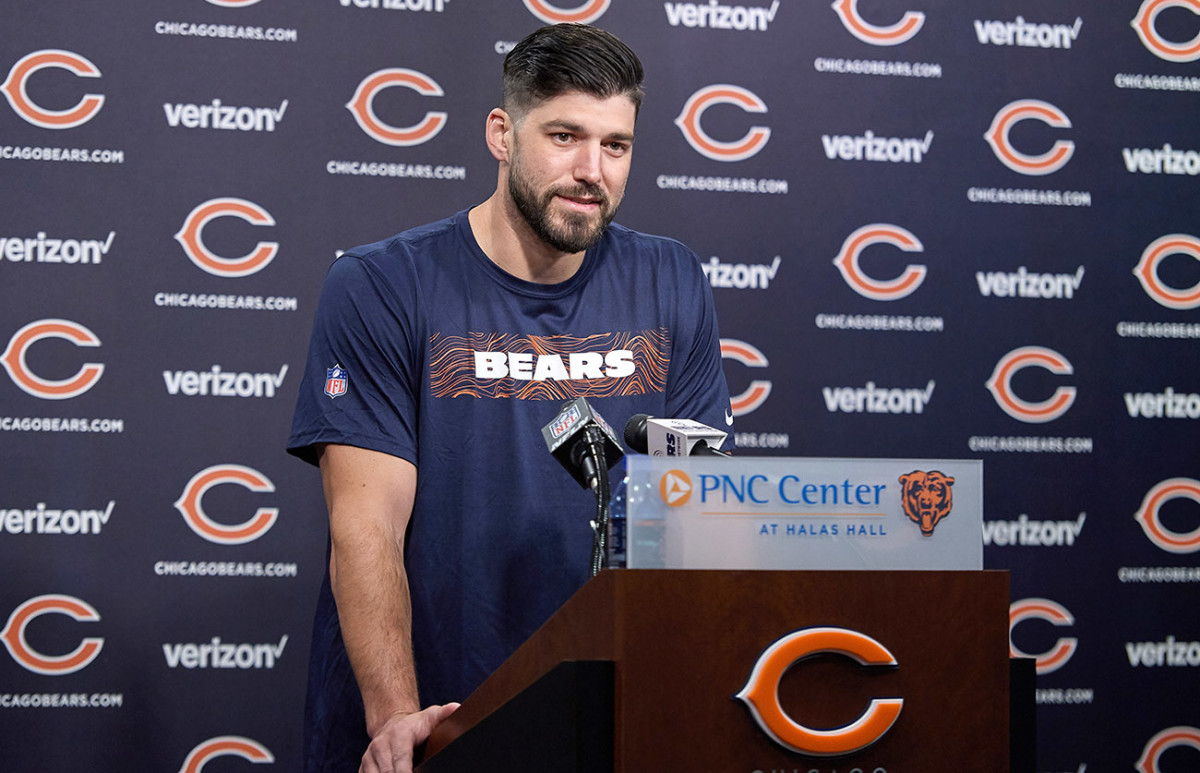

“I haven’t been told no,” he said in a press conference three weeks ago, held on the one-year anniversary of his injury. “I haven’t been told yes. It’s kind of just a day-to-day thing. I know there will be a point where I’ll be able to decide that. I’m not there yet.”

For now, he’s focused on doing all he can behind the scenes in the second half of the season for a revived Bears team that hasn’t played in the postseason since 2010. “He is a picture of perseverance and dedication, everything you want in each of your position groups,” Ragone says. “He is just a walking example of what all of us should aspire to be.”

Against all odds, Miller is now a running example.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.