How Did We Let James Hardy Slip Through the Cracks?

The remains came to rest in a tangle of logs, swept there by the mud-brown river surging toward flood levels in the wake of spring rains. On June 7, 2017, the smell of decay from the Maumee drew a worker from a nearby water filtration plant. By the late afternoon responders had unmoored the body, but after snaking through the river’s bends for days its identity initially proved indeterminable.

First, word came from the Fort Wayne, Ind., media: another corpse found in the water, the second in recent weeks. Then whispers. Then texts and phone calls: You know that person they’re talking about? It was James.

Here, “James” clearly meant 31-year-old James Hardy. Brandon Stuckey, who had shared a basketball court, a locker room and impossible dreams with Hardy at Elmhurst High, dropped his phone when he heard the news, then walked out of his job overseeing community-service trash pickup. Keith Edmonds, the high school basketball coach who had accompanied Hardy on unofficial college recruiting visits like a proud parent, refused to believe . . . until he returned home to find TV vans assembled outside. Roosevelt Norfleet, a first cousin and, for a time, Hardy’s guardian, cleared the staff out of his office at a Fort Wayne high school to sit in solitude. Jeanie Summerville, Hardy’s mother, received the news in a morning voicemail—the county coroner had left a message as she slept.

Kyra Nolan, en route to an Ohio amusement park when she got the call, stifled tears for the sake of her son, James. She would permit the 11-year-old in the backseat one more day of innocence before introducing him to life without a father. The boy’s face was tattooed across Hardy’s chest—an image that helped the coroner attach a name to the body.

A disconnect fueled collective disbelief. That waterlogged corpse couldn’t have been the same six feet, six inches and 220 pounds of sinew and strength with which Hardy had bent the world to his will; the vessel through which he’d made an antique gym—concrete risers, stiff benches—throb on those long-ago winter nights. When Hardy’s mind insisted that a great feat loomed, his body had made it so: a 56-point outburst in a high school basketball game; his name atop every significant Indiana receiving record list; an NFL career that, at least for a while, would elevate him above the miseries of his youth. “He would speak things into existence,” says Stuckey.

But that body had begun to fail. And as the vessel withered, so did a mind that was hard-wired to believe in its ability to conjure greatness. A mind that believed only pain lurked outside the spotlight.

What happens when a man believes he has made the world conform to his wishes—and then finds he must conform to the world’s? For Hardy, it meant that a damaged body would drag a fragile mind down with it, all the way to a winding river and a closed casket.

“Of all people,” wonders Chad Edmonds, Hardy’s Elmhurst High basketball teammate, “how did we let James Hardy slip through the cracks?”

When Hardy moved into Norfleet’s two-bedroom apartment before his sophomore year of high school, he was too frail to support the expectations that would come later—and that frailty extended beyond his lanky 6’4”, 160-pound frame. His father had been imprisoned for nearly a decade on drug charges; his mother’s presence was erratic, according to Hardy and several people close to him. (Summerville says that she was a constant in her young son’s life, squiring him to football practices and wiping his runny nose between plays.) James spent his adolescence caroming around Fort Wayne, crashing with his grandmother or with an uncle, sleeping sometimes on a mattress on the floor, often unsure of his next meal. Summerville says their time living apart was due to her son’s desire to play at Elmhurst and be closer to the school. Friends and family tiptoe around the difficulties of James’s youth, wary of denigrating his parents. But the hardships are implicit in the silence between their stammers and sighs and I’d rather nots.

Although Norfleet was only 11 years older than his cousin, he was named Elmhurst’s football coach before Hardy’s junior year. And with the keys to the athletic facilities the two young men dedicated their free hours to moving iron in the school’s cramped weight room. Norfleet would also unlock the gym and retrieve endless jump shots. Make three in a row before you move to the next spot; 500 a day—at least. On weekend mornings Stuckey remembers his friend rising after a sleepover, wordless, to strap weights to his ankles, then pounding the pavement in the predawn darkness.

Hardy found purpose and, for the first time, stability, through training and the mastery it brought. He led the Trojans to the state title game as a junior guard; the next year he finished third in voting for Indiana’s Mr. Basketball. He scored 10 touchdowns as a senior receiver, snatching balls over smaller defenders. “He literally grew up hungry,” says Bryan Payton, a Fort Wayne rival and later a teammate at Indiana. “And when you grow up hungry, you play like that.”

Hearing his name ring throughout Fort Wayne sated Hardy’s hunger, but it also bred expectations. In school hallways he signed autographs for his peers. He could skip classes without repercussion and leave campus for lunch while others loitered in the cafeteria. In the mall people stared and shouted unabashedly at the tall boy with the angular face and stylish threads. A friend working at one department store would let Hardy and Stuckey, a teammate in both sports, waltz out with designer clothing befitting their status. “We just didn’t accept no for an answer,” says Stuckey.

The word impossible grew to mean nothing. Elmhurst’s football team was mired in one of the worst losing streaks in the country—64 straight—when in the opening game of Hardy’s senior year he caught three TD passes to help upset the previous season’s state runner-up, Bishop Dwenger. In the aftermath Hardy was interviewed by The New York Times. David Letterman even noted the feat.

In Sanders Tucker, a running back and safety, Hardy found a teammate who could relate to the hard life before touchdowns and the Times. Tucker, too, had ricocheted through childhood, had watched a parent hauled off to prison. He was prone to vicious shifts in mood, and when conflicts arose Hardy was routinely there in his defense. Hardy recognized their shared suffering, but he also understood his own advantage. Tucker lacked the 6’6” suit of armor. His room wasn’t littered with recruiting letters—from Michigan State, Indiana, Connecticut—that, to Hardy, portended uncertainty’s end.

Sitting on Norfleet’s apartment balcony on a brisk fall afternoon, Hardy offered his friend what comfort he could. “When I make it,” he told Tucker, “we all gonna make it.”

“I don’t need this!” Hardy pleaded, his long frame crammed in the back of a squad car. “I’m the best thing coming out of Fort Wayne!”

Hardy had been visiting Nolan, his longtime girlfriend, in May 2006, when she picked up a phone and wailed to a police dispatcher that Hardy had hit her and her baby. That child, James Hardy IV—Little James to his father—had come into the world six months earlier. Father held son that day and cried, vowing to be present and to provide.

But now Nolan was sobbing, her sweatshirt torn, her cordless phone shattered into four pieces in the melee, according to the police report. As the consequences of her call grew clearer, she changed her story to police. Nothing had happened.

“I am trying to go pro and I don’t need this,” Hardy said from the back of the cruiser. “A lot of people look up to me—what will they think now?”

Unswayed, officers charged the 20-year-old with domestic battery and interfering with the reporting of a crime. (He would avoid a jury trial by agreeing to take part in an anger management and communications skills program.)

Indiana football coach Terry Hoeppner and his wife, Jane, picked Hardy up after the incident and sped him back to Bloomington. In him they saw an earnest young man who required a steady hand. Coach and pupil would spend hours discussing Hardy’s youth in the football office or on a university-issued golf cart, riding around campus. In the Hoeppner living room Hardy explained to Jane the type of father he yearned to be.

Hardy had arrived in Bloomington as a two-sport athlete in a basketball-mad state, but after averaging just 1.7 points as a freshman he focused fully on football, and he began to reward the Hoeppners’ investment. A receiver with a small forward’s fluidity, he was intent on taking whatever path perpetuated his life as James Hardy and ensured riches for Little James. When he demanded that receivers coach Billy Lynch make him the best in the country, “he meant it,” says Lynch. “And he went to work.”

As the numbers accumulated on the field—he would leave with Hoosiers career records for receptions, yards and touchdowns—Hardy gave up his usual nights out for a quieter college life. The police incident spurred him to become more cautious, and despite the chilling altercation, Nolan moved to Bloomington, where the couple shared an apartment away from the heart of campus, children’s toys dotting the floor. During summer seven-on-seven drills father tended to son between routes.

Those tender moments were balanced by a distinct edge—Lynch and Hardy often howled at each other in practice, and the receiver routinely berated teammates after mistakes—but his peers and coaches never saw any signs of mental decline. Any volatility, coaches insist, seemed typical of a hormone-fueled college kid. Or maybe that edge was just too easy to excuse in a player who scored 16 touchdowns as a junior, second in the nation to Texas Tech’s Michael Crabtree.

Hardy announced in January 2008 that he was forgoing his senior season for the NFL draft, but not before fate punched one more hole in his heart. Hoeppner had succumbed to brain cancer in June ’07. Speaking at the coach’s funeral in Assembly Hall, Hardy tried to encapsulate what it meant to find the father figure he had long sought, only to lose him. For eight minutes his subdued voice commanded the room.

“He helped me when I was at the lowest point of my life,” Hardy told a crowd of several thousand. “He knew the type of person I was. He wanted to make sure everyone else knew.

“I just don’t know what I’m going to do without him.”

Fifteen days after the Bills took Hardy with the 41st pick, in April 2008, a witness told Fort Wayne police that she saw the young man punch his father, then draw a gun and flee. James Hardy II, then 43, explained to the responding officers that he had spent his son’s childhood in prison, and that the young man’s anger over that had not abated. Still, for the sake of his offspring (and an extended family that needed him to thrive), the elder Hardy refused to corroborate the witness’s account. No charges were filed. (Hardy’s father declined a request to comment.)

Later that summer, at the NFL rookie symposium in Carlsbad, Calif., retired receiver Cris Carter brought up the incident and admonished Hardy in front of a small group of draftees. You just don’t get it, he warned. Emasculated and embarrassed, Hardy retreated to Fort Wayne, straight to Norfleet’s door. Frightened of bungling the only life he’d ever envisioned, he asked his cousin through sniffles to come live with him in Buffalo. Norfleet agreed. (Nolan declined the same offer. Too many battles, she says. Too many other women.)

Hardy bought a house near Ralph Wilson Stadium, in Orchard Park. Thirty-five hundred square feet. A 70-inch TV with surround sound. A $100,000 custom Range Rover. A $30,000 necklace. “Stuff he’d never had in his life,” says Norfleet. Too much. But Hardy had just cashed a $1.4 million signing bonus, and so he spent his new fortune while Norfleet drove him to events, cut the grass, helped him study the playbook, kept an eye on household finances, even shuttled Little James back and forth from Indiana. Mostly, though, Norfleet fretted as Hardy leaned less on his cousin’s grounded advice and put faith in his monied peers. Teammate Donte Whitner recommended a personal stylist and Hardy jumped. (A $28,000 bill came later.)

Maybe all of that would have been fine if the money kept coming in, if everything had gone according to plan. But on Dec. 14, 2008, in the first quarter of a Week 15 game against the Jets, Hardy was blocking downfield on a 35-yard Marshawn Lynch scamper when he fell awkwardly and tore his left ACL. The rookie who expected he would be the Bills’ best receiver instead finished the season with nine catches for 87 yards and a pair of TDs.

In the wake of surgery, Hardy slid from brash to morose. And Norfleet absorbed the brunt of that frustration, which Hardy dismissed by reminding his cousin who was paying his room and board. Tired of being belittled, Norfleet returned to Fort Wayne in March 2009, leaving Hardy alone with his doubts.

The following season Hardy appeared in only two games for Buffalo, and he found himself a training camp casualty the next fall, leaving him with just 96 total yards (and $2.9 million) over two seasons.

Fort Wayne received him with reverence whenever he returned. He led turkey giveaways on Thanksgiving; the city even dedicated a day—June 13, 2009—in his honor. But the incessant questions about when he might get back on the field called more attention to who he wasn’t than to who he was. People wanted to know, demanded to know: When would they get to see James Hardy again?

In 2010, Elmhurst High was set to be shuttered after 81 years, a budget casualty, when Hardy stood before three classes of students and bid farewell to the small brick gym to which he’d so frequently given a heartbeat. He strained for optimism in addressing teenagers whose lives had unexpectedly shifted. “Sports were my outlet,” he told them. “If you have goals and things change, good things can happen.”

Goals, though, are not guarantees. When the Ravens signed Hardy in January 2011 they got a receiver with a balky hamstring and a rebuilt knee. Baltimore cut him that September. He was 25.

Jane Hoeppner returned to Assembly Hall in May 2011 and watched, awash in pride, as one of her late husband’s most revered players graduated. After Hardy had left Indiana early she sent encouraging letters and books, and he returned to Bloomington that January, during the NFL lockout, to finish his general studies degree. (In what would later prove a grim irony: Hardy helped satisfy his final 12 hours of credits by taking a swimming course. “I am definitely not scared of that water anymore,” he told The Indianapolis Star.)

But a degree proved more endpoint than launching pad. After being cut by the Ravens, and then getting nowhere in the Arena League, Hardy craved the kind of adulation to which he’d grown accustomed—the kind that a general studies degree could not readily provide. He’d already had a brief stint on a short-lived BET reality show, Tiny & Toya; maybe, he thought, his future lay in Hollywood, acting, modeling, rapping. He tuned out pleas from friends to consider a more mundane pursuit. “He didn’t want to go back to where he was when he was younger,” Tucker says. “He didn’t want to live like that no more.”

The NFL and NFLPA have instituted a handful of initiatives in recent years to help players navigate these kinds of transitions. One of those, the Trust, launched in 2013 with an annual budget of more than $20 million. Entry is an earned benefit, similar to a 401K or pension, available to players with at least two accredited seasons (three or more games on an active roster or IR), and so far about 1,000 former players have enrolled per year.

“He didn’t want to go back to where he was when he was younger. He didn’t want to live like that no more.”

After an eligible player contacts the Trust he’ll work with a program manager, who connects him with an appropriate partner organization in, say, continuing education or financial services or, most vitally, career counseling and mental health. “One of the things that may seem basic but I’m not sure happens with a lot of former players is somebody asking them, ‘What are your interests beyond football?’ ” says Bahati VanPelt, the Trust’s executive director. “Sometimes the guy has never thought of what his identity would be because he’s never been asked.” Hardy, at some point, enrolled in the Trust. As a rule, the group won’t reveal what services were offered, but in cases involving mental health issues they’ll often direct players to the confidential NFL Life Line, launched in the wake of Junior Seau’s 2012 suicide, which connects callers to mental health professionals in moments of need or crisis.

A psychologist evaluating Hardy at the time might have noticed signs of athletic identity foreclosure, which occurs when an individual builds an existence around athletic prowess and its spoils in late adolescence, adopting a single-minded drive during a time when the brain requires nourishment from varied interests. Consequences later in life vary depending on circumstance, but they can include heightened vulnerability to mental and developmental issues.

Experts warn that receiving the type of special treatment Hardy did at a young age due to his athletic exploits—being permitted to cut class, steal clothing and skate around legal troubles with few consequences—can intensify identity foreclosure. And significant injuries often ignite its fallout, says Britton Brewer, a professor of psychology at Springfield (Mass.) College, steering athletes toward darker thoughts and moods like those Hardy demonstrated after his ACL tear and subsequent physical struggles. Unless athletes with these identity problems can find fulfillment in other endeavors, says Brewer, they are more susceptible to depression—or worse—when they step out of the limelight. The issues can be particularly pronounced among those who are genetically predisposed for mental health problems. “It’s like you’ve got a tire that has some bald spots,” he says. “You’re vulnerable.”

The last time Jane Hoeppner spoke on the phone to Hardy, about four years ago, she didn’t hear the ebullience or confidence that she remembered from graduation day. He’d fathered a daughter during his time in L.A., where he lived in a relatively plush downtown apartment, but had gotten nowhere as an actor or model. He had severed ties with Stuckey and Norfleet over petty squabbles and made only occasional trips home to see his son. “James would come [to town],” Keith Edmonds remembers, “and he’d be out like a vapor.”

The defeat Hoeppner had sensed on the phone proved a harbinger. In May 2014, spooked by an argument inside Hardy’s apartment, neighbors called the LAPD. The arriving officers ended up firing a taser at Hardy, but he pulled the wires from his body and fled. Two cops chased him down and arrested him—during the scuffle the officers sustained injuries that required treatment.

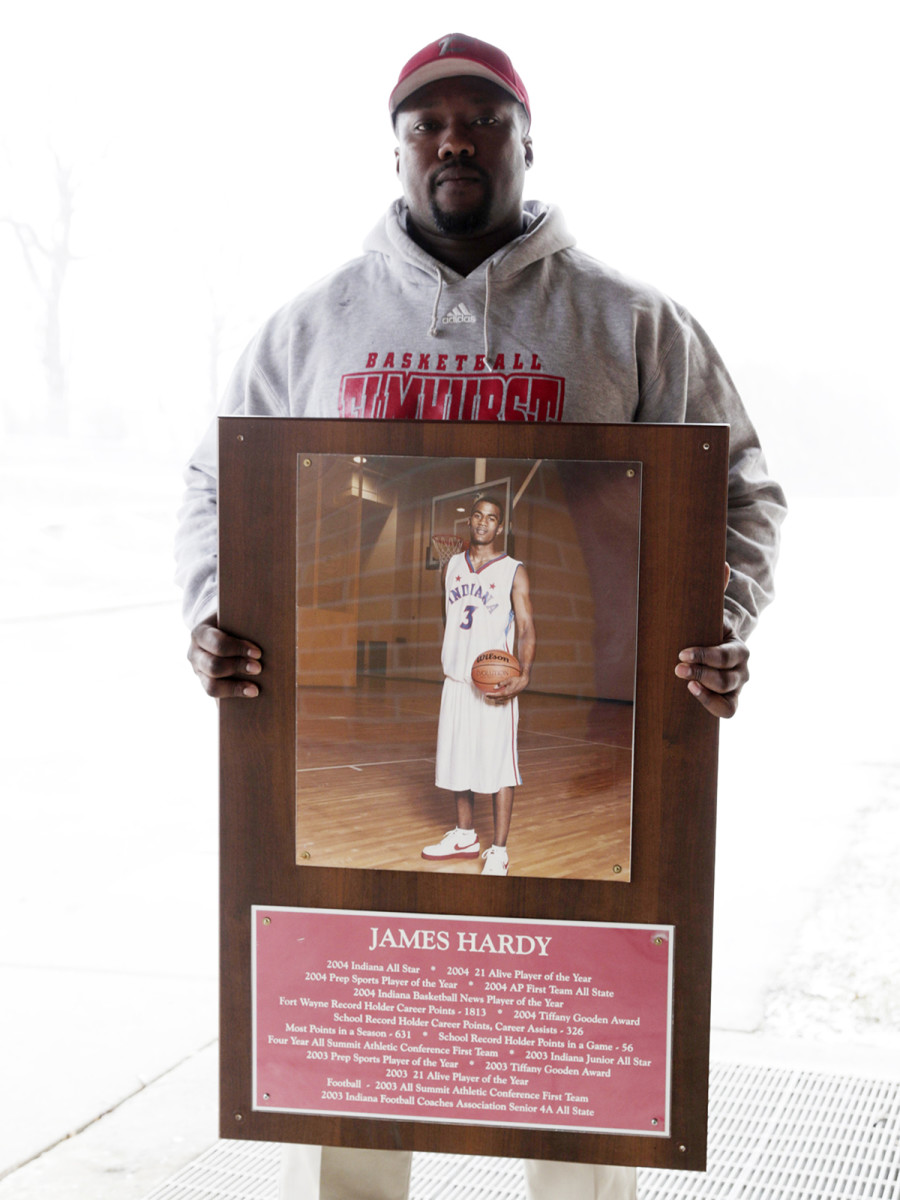

Roosevelt Norfleet was Hardy's first cousin and, for a time, his guardian.

Hardy broke his silence with Norfleet, calling him from lockup. “You’ve got to get me out of here,” Hardy pleaded. He claimed that the reports in the media were false, that police had abused him in the tussle. Hardy’s agent, Eugene Parker, sent a lawyer, who suggested a plea deal, but Hardy told his cousin he was certain Parker and the lawyer were conspiring to keep him confined. Norfleet called Parker, who said Hardy had been speaking in gibberish. Reality had begun to elude him.

In November, after a psychological evaluation, Hardy was remanded to Patton State Hospital, a forensic psychiatric treatment center 60 miles east of L.A. That evaluation remains sealed (Patton cannot release any records or reveal the duration of Hardy’s stay), but a judge declared the defendant mentally incompetent to stand trial and cleared Patton to administer involuntary antipsychotic medication. Hardy was to be confined at Patton no longer than three years and eight months, minus time served.

Summerville estimates her son remained there roughly one year; Tucker recalls it being only a matter of months. Either way, when Hardy eventually returned to Indiana in 2016 his outward appearance finally reflected the turmoil within. An untamed beard hid a once stone-cut jawline and wild hair framed his face. His body, that magnificent vessel, had begun to soften and waste away.

In the last months of Hardy’s life, Little James knew his father only as a pixilated visage with a garbled voice. A Fort Wayne court had ordered that twice-weekly Skype sessions be the extent of Hardy’s contact with his son. But often, instead of a chat, Little James would stare at a blank screen for half an hour before sending texts to his father, imploring him to log on.

On the occasions they did connect, the 11-year-old boy discerned differences in his dad, but he looked past those problems, happy for the moments spent speaking with his idol. Maybe, his mother told him, they could spend time together again, provided Hardy kept his requisite therapy sessions. Nolan had married and had another child, and still she helped pay for her ex’s treatment when others in his family wouldn’t. (Hardy rarely showed up for these sessions.) On Jan. 24, 2017, Nolan had her last interaction with her son’s father. In a text, Hardy asked who was teaching Little James how to play basketball.

Back in Fort Wayne, Hardy moved into his maternal grandmother’s house—his own mom, Jeanie Summerville, was staying there too—and receded into the kind of life he’d once devoted untold amounts of sweat toward escaping. With his NFL money dwindling, he sold the custom Range Rover to Parker’s son for $30,000. He avoided public interactions in the city where seemingly everyone knew his face and name. Tucker says his friend loathed the continued queries about where he was playing ball. When he said his career was over, jaws dropped and conversations stopped short. People expecting a deity got only a man.

Hardy hadn’t yet given up on the deity. He trimmed back his long hair and beard and began frequenting a YMCA on the south side. He asked Keith Edmonds, the old high school coach, to push him through some workouts; maybe he could earn a tryout with the NBA Development League’s Fort Wayne Mad Ants. But after a few sessions—his dribbling sloppy and jump shot off—it was clear: James Hardy would not find what he sought. “It’s almost like when you’re a superhero and someone puts kryptonite [near you],” says Edmonds. “He just didn’t have it.”

After those failures, Hardy griped to Edmonds about the rigors of compiling a résumé—he had no idea how. He asked friends for leads, reached out to youth organizations, contacted local schools. Does anyone need a coach? But here, in the city that once named a day after him, James Hardy finally heard no, again and again.

Norfleet caught only a glimpse of his cousin during this time back in Fort Wayne—Hardy was painting his grandmother’s porch—but gossip about run-ins with police offered a glimpse into his well-being. On one occasion Hardy was seen galloping down his grandmother’s street wearing a diaper, screaming. On another, he asked his uncle about the existence of an alternate dimension, then pointed a pistol at his own temple and threatened to pull the trigger. When police arrived, Hardy denied having any mental disorders but admitted he was seeing a psychiatrist to address his depression. He said flashbacks of being attacked by police officers in L.A. haunted him.

Finally, inevitably, the living situation at 225 East Butler Street boiled over. On March 31, according to a police report, Summerville called authorities to her mother’s home. Jeanie and James had been arguing: She demanded that he apologize to the uncle he’d terrified with the gun, and she wanted James gone; he refused and alleged that she was a junkie. (Summerville says that her son sought only to embarrass her in front of police and that she didn’t want him to leave, just to calm down.) The responding officers, noting that the home reeked of urine, left amid the shouting match, but not before pleading with them to clean the place, for the grandmother’s sake. Both refused.

Keith Edmonds’s uncle owned a home—one story; peeling pink paint with green trim—only four houses down the street, and Hardy moved in alone. There he began having productive talks with Tucker, the friend he’d defended through high school, who now hoped to reciprocate. During a crucial three-hour call in late May, Hardy told Tucker he would apologize to Norfleet for disparaging him then shutting him out, that he meant none of it. He mused about doing the same for others he had pushed away, about mending relationships scarred by the stubbornness with which he’d masked the shame of not delivering on his promise. We all gonna make it.

Hardy went to pick up a used, gray Chevy Malibu in Ohio to replace his Range Rover—a pedestrian car for a pedestrian life—and assured Tucker he would see him in a few days. Instead, police found Hardy in that Malibu on May 25 after passersby reported seeing him circling a block, harassing schoolgirls at a bus stop. Officers warned Hardy to stay away but let the jittery man they encountered go. Five days later Summerville again beckoned authorities to her mother’s home, this time to report not that she wanted her son gone but that she couldn’t find him. She’d last seen him on the day after the bus stop incident; he’d insisted to her that he would kill himself. Tonight’s the night. According to the police report, she told officers that her son suffered from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression, and that he had bandages around his neck from a failed hanging attempt one day earlier. (No physician has ever publicly verified these diagnoses; Summerville now denies that she cited these diagnoses to police.)

Summerville pointed the officers down the street, fearing they would discover her once-celebrated son hanging in the pink house with green trim. They found the unit unoccupied, a half-dozen trash bags filled with personal effects scattered across the back porch. Years-old letters of encouragement from Jane Hoeppner sat among his belongings.

In the days before his disappearance it seems Hardy tried to fulfill the promises he made during that long talk with Tucker. Stuckey received a series of calls from a California number that he didn’t recognize. Today he laments not answering. Keith Edmonds traded texts with Hardy, player asking coach if they could reconvene, but Edmonds was headed to Cincinnati for an AAU tournament. They made plans to talk when he returned. When Edmonds finally called, no one answered.

Norfleet received texts, too: an apology, a vow to repair the damage done by a bruised ego and a deteriorating mind.

“Nobody can stop me from loving you,” Norfleet responded. “Not even you.”

Little James spent June 8 riding roller coasters at Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, while his mother watched from afar, eventually turning off her phone as a deluge of messages flashed across the screen. The next day Nolan drove two hours and 45 minutes back to Fort Wayne, sat the boy down in her parents’ living room and, with a few words, killed his hero.

It took six weeks before the coroner released the cause of death: asphyxia due to drowning. Self-inflicted.

Could CTE have contributed, as it is believed to have with other former NFL players whose lives met desperate ends? The parallels seem evident, but Hardy’s brain was never sent away for study. Nolan says Hardy underwent a thorough physical examination, including a brain evaluation, at the Cleveland Clinic before he passed away, but, citing privacy laws, the hospital cannot confirm if he visited or what tests were rendered, if any.

The coroner’s delay, coupled with Hardy’s being the second body pulled from the river in as many weeks (plus another fished out of a nearby pond), roused speculation. Tucker, for one, remains confounded by Hardy’s car purchase, by his eagerness to find a job and reconnect with loved ones. Why would he go through all that effort, only to end his life?

Norfleet wonders whether Hardy’s volatility drew the ire of the wrong person. He’s certain the cousin he knew wouldn’t kill himself. And Stuckey, despite years of distance, refuses to believe the man who led the life he envied most would have willingly ended it.

Nolan, though, has no difficulty processing the notion that James Hardy tossed himself to the mercy of a raging river. He may have hidden his most intimate frailties from his male friends, but his on-and-off girlfriend of 10 years says he’d raised the idea of suicide with her before. She’d held him off with talk about being too young and having so much life ahead of him; she reminded him of the two children who needed him. In the end, though, “he couldn’t handle it,” she says. “I think he gave up.”

Hardy’s funeral, held 10 days after rescuers plucked his body from the river logjam, drew a respectable crowd, but it seems likely that there would not have been a swath of empty seats in Fort Wayne’s New Covenant Worship Center had he passed away a decade earlier. The NFL Player Care foundation helped with some of the expenses, but outstanding costs remained. Nolan took on those financial responsibilities herself and oversaw the planning. Though her relationship with Hardy had been darkened by other women and a phone call to police, she wanted to give him a ceremony worthy of his name—and one last day of relevance in Fort Wayne. More than that, though, she says she did it for James IV. Despite Hardy’s failings, the boy plays football and basketball, just like his dad, hoping to elicit pride from afar. “My son loved him,” Nolan says. “He wants to work hard for him.”

Little James, with Nolan at his side, went to weekly therapy in the first couple of months after his dad’s death in hopes of sorting out the complications of being James Hardy’s offspring. Today he goes occasionally, as needed—holidays and birthdays have proven particularly painful. Mother and son frequent Concordia Cemetery Gardens, tucked between cul-de-sacs and a narrow basin dotted with geese, and mother keeps her distance, leaving the boy alone so he can say what he must.

Each day, Little James looks a bit more like the black-and-white photo of his father etched into the tombstone. Only 13 years old, he already wears a size 13 shoe. At 5’ 7”, he’s already taller than his mother. Norfleet sees the father’s same long, lanky frame before it filled out. He sees the same loose, uncoordinated movements that grew more precise with each workout, as mind pushed body until it became strong enough to shoulder the expectations of family, friends, a city—until it couldn’t.

Today Norfleet is the football coach at South Side High in Fort Wayne, and he hopes Little James will come play for him. Maybe Norfleet will help mold that spindly frame into one that can deliver on impossible dreams. He aches for another chance.

James Hardy III left pieces of himself behind, enduring bits cultivated on courts and fields. Stuckey hung on to basketballs from their time together in high school. Tucker’s prized memento is a crimson Indiana jersey, number 82, framed and autographed by the friend who’d agreed to be the best man at his wedding this November.

As Elmhurst High sat vacant since 2010, looters slunk through its abandoned hallways, ceiling tiles missing, to gather the prizes that Hardy had long ago earned. A litany of trophies and plaques and photos—for team sectional and regional appearances and for finishing state runners-up; for all-city player of the year and all-state in two sports—had once rested behind glass cases and hung on gym walls. And while many of those treasures were plundered as the pale brick building sat neglected for years, Norfleet managed to collect a few of the remaining relics, tucking them away in his garage.

The owners of a neighboring quarry purchased the old Elmhurst High site last August. Demolition began this spring, and the surrounding 27 acres will soon be cleared to mine for limestone. Despite efforts to save it, the cramped old gym that once heaved to life as Hardy glided down the court has collapsed in on itself.

Workers will soon clear the rubble and begin digging. In the school’s place, only a chasm will remain.