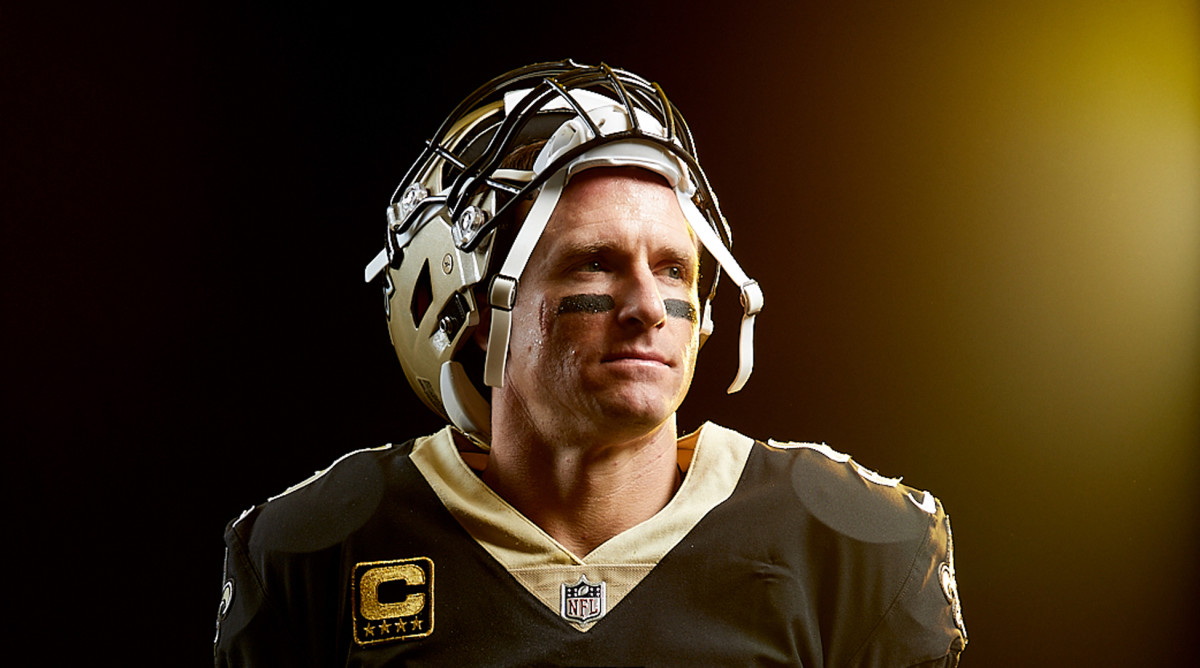

Drew Brees Is Hiding in Plain Sight

Drew Brees spies the bouncy house—the friggin’ bouncy house—and grimaces. He’s on the field at the Saints’ indoor practice field in mid-October, holding an inch-thick black playbook and rifling through pages of plays named after video games (Fortnite) and superheroes (Black Panther, Captain America). He turns to address the Boilermakers, the team of first- and second-grade flag footballers he coaches every Monday. He’s oblivious to the parents seated in their lawn chairs, to the dogs roaming the sidelines and to the most repeated question of this 2018 NFL season: What record did Brees break this week?

The kids, though, are not oblivious. They’re distracted. By the parents and the dogs and, most of all, by the giant bouncy house now being inflated across the field for the birthday party of coach Brees’s middle son, Bowen, who is turning eight. Sure, Brees may have vaulted the Saints into Super Bowl contention while expanding the footprint of his youth flag league, Football ’N’ America; he may have toppled the NFL marks for career completions and passing yards, thus (slowly) altering the prism through which we view his remarkably-consistent-and-still-not-yet-fully-appreciated career. But right now the 39-year-old is competing for attention against more than Tom Brady or Aaron Rodgers or Peyton Manning, or even the overcooked notion that he’s some sort of football underdog success story. Now it’s Brees vs. the Bouncy House too.

Deterred? Please. This is a man who takes his flag football so seriously that he cornered LaDainian Tomlinson over breakfast at the Pro Bowl last January and discussed flag formations, with a particular focus on motioning backs—second-graders!—out of the shotgun. If Brees can overcome shoulder surgery, short-quarterback problems and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, surely he can wrangle a bunch of kids through practice. Right?

“Everyone’s going to catch a ball,” Brees tells the kids in his well-worn dad voice. “Then we’ll go over to the bouncy house.”

“I’d rather go therrre,” pleads Bowen, who was born eight months after his father won Super Bowl XLIV in 2010.

“I know you would,” Brees says patiently. “But we have to do this first.”

Later, after practice, as Bowen bounces and Brees cuts slices of Fortnite-themed cake and asks his daughter, Rylen, where her shoesies are, no one mentions the events of the previous day. Not the Saints’ 24–23 victory over the Ravens, the only team Brees had never beaten. Not his 500th career TD pass. Not the fact that he bolstered his league-leading marks for efficiency (121.6) and completion percentage (77.3%) and had still yet to throw an interception. “Great game yesterday,” one parent musters. That’s it.

It can seem like Brees prefers life this way, content to let his contemporaries be described as nonhuman quarterback deities. Brady, with his supermodel wife and all those rings, the holistic health guru who just might play forever; Rodgers, the golden-armed God with the celebrity girlfriend, helming an iconic franchise; and Manning, the genius gridiron savant. Meanwhile, here’s Brees, this middle-aged guy, just plugging along off to the side, coaching flag football. Because of that image, and because of a series of events from early in his career, he’s portrayed as merely human—or rather, something less than superhuman like the others.

In other words, Brady and Rodgers and Manning are the bouncy house. We’re the kids, mesmerized by these shiny distractions. Brees is just Brees, the dad toiling in the shadows. And that notion of Brees as the plucky everyman is not merely overly simplistic. It’s wrong. In reality, he’s just like them, a psycho-cyborg QB. One of the greatest players in NFL history.

The proprietor of the Mother-in-Law Lounge in New Orleans knows his history. Kermit Ruffins—trumpeter/singer/composer/Saints fan—wore his black number 9 Brees jersey for 15 straight days this fall, not wanting to mess with his quarterback’s mojo. “Brees sets the tone for the city the same way musicians and chefs set the tone,” says Ruffins. “Playing his ass off like that at almost 40 years old—that is freakin’ gangster! Anything else you think gangster ain’t gangster!”

Ruffins takes a long pull from a Bud Light. “History is funny, man. Sometimes it sneak up on you.”

In fairness, this season of records broken crept up on Brees, too. Growing up in Austin, he played flag football until ninth grade, made forays into tennis and track and basketball and baseball, and almost quit the jayvee football team. The only history he cared about at that point was becoming the first athlete to play professionally in three sports.

Sure, as a Cowboys fan he loved Troy Aikman, and he emulated Joe Montana, John Elway, Dan Marino and Jim Kelly. But he only came to appreciate that last golden age of quarterbacks in hindsight. As for his current place among, if not above, them? “I don’t think that was ever on my radar,” he says. Really? “Honestly.”

Brees still remembers his first preseason game, in Miami with the Chargers in 2001, and how he looked to the upper deck and saw Marino’s name up there, next to all of the Dolphins legend’s gaudy career accomplishments. But it wasn’t as if Brees resolved at that moment to pass Marino in every statistical passing category known to man. Instead he thought, Hey, don’t screw this up; let’s just try and complete some passes today.

So that’s what he did. He wanted to become a starter. Lead his team to the playoffs. Find a franchise that wanted him. Make the Pro Bowl. Win a Super Bowl. Then one day he woke up and he’d done all that, in 10 years. He decided he’d aim to play until he was 35, at least. When he did, he resolved to try for 40. And then, this summer, he looked at the Saints’ 2018 schedule and noticed the Redskins game in Week 5, in prime time. It was almost as if the NFL expected something—like, maybe he’d break Manning’s all-time passing mark. (Coming into the season Brees sat at 70,445 yards; Manning retired in ’15 with 71,940.) The league’s decision struck Brees as a tad presumptuous. He’d have to average 300 yards a game to get there. “At that point,” he jokes, “it’s like: All right, no pressure.” Then he resolved to “play ball. Make them right.”

As Oct. 8 approached, Brees worried most about the kinds of things only Brees would worry about. That he might break Manning’s record late in the game, in the middle of a critical drive, halting his team’s momentum. Instead, as if scripted, his family made its way onto the field late in the second quarter. Brees found rookie wideout Tre’Quan Smith streaking up the right sideline unattended, lofted a perfect spiral and watched Smith carry him, 62 yards later, into history.

Brees remembers every detail about the aftermath. Hugging tackle Terron Armstead. Searching for his coach, Sean Payton. Embracing his wife, Brittany. Telling his four children they can accomplish anything they work for. Handing the ball over to Pro Football Hall of Fame president David Baker. “Perfect,” Brees says. Baker wore white gloves for the occasion, ensuring that the last hands to touch the ball were those of the man who threw it. He placed the pigskin into a black cinch bag held by a Hall of Fame researcher, Saleem Choudhry, who would fly it back to Ohio the next morning along with a Saints equipment bag containing the QB’s jersey, pads and everything else he’d worn that night. Choudhry said he protected the gear “like the Hope Diamond.” Brees, typically, kept only a game program and a call sheet.

Later that night he decamped to Rock-n-Sake Bar and Sushi. Over sashimi and wontons and pork-belly lettuce wraps, he told a small group of close friends and family what they meant to him. Former president Barack Obama would later call the QB “a class act.” Manning would joke that all he had left in life, after his record fell, was “making dinner for my family.” Brees’s friend and former Saints teammate, Scott Fujita, would say, “I’d argue he’s playing the best football of his career.” His trainer, Todd Durkin, would say, “We’re watching Picasso with his paintbrush.” At dinner, though, the discussion never touched on Brees’s place in history. And that was fine with the guest of honor, the record breaker who never bought into any narrative laid out for him.

Even with a bye the next week, Brees wasted no time on reflection. He tried, instead, to dig into his latest read, Things That Matter. He would like to be able to describe the impact the book had on his historic season. He would like to be able to describe the book at all. But the truth is, if he can make it through 10 pages on a given night, he considers that a win. If that makes him sound more like an exhausted dad than a football legend, so be it.

“I don’t get it,” James Carville says over a glass of Woodford Reserve and a plate of pasta at an Italian restaurant in Baton Rouge. “It’s like living in New York in 1926, when Babe Ruth was there. Or Chicago in 1995, with Michael Jordan. To actually live in a city where Drew Brees is critical to our lives 16 days a year—it’s stunning. He’s become like the river. He’s just a part of us.” The Ragin’ Cajun continues: “People want to talk about how [Brees] never won MVP, [just] the one Super Bowl. . . . What difference does it make? Ted Williams never won a World Series. He’s still Ted f------ Williams.”

The problem with Brees and his place in the pro football pantheon is that the story of his career, while fascinating, inevitably leads us to the absolute wrong conclusion. Consider the facts: Yes, Brees did tear his right ACL late in his junior year at Westlake High in Austin. No, he was not recruited by the local powers, the Longhorns or the Aggies. Yes, he did fall to the Chargers in the second round of the 2001 NFL draft, in part because of his height: an even 6 feet. He did struggle (by his eventual standards) in his first two seasons as a starter. The Chargers did draft Philip Rivers in ’04, and Brees did win the league’s Comeback Player of the Year Award that season, essentially for thriving in the face of doubt. He did dislocate his throwing shoulder in ’05, undergo surgery, suffer through free agency, land in New Orleans and lead the city, still reeling from Katrina, to its first and only Super Bowl win in that magical ’09 campaign.

The shoulder surgery was epic. The doctor who performed it, James Andrews, says now, “Probably one in one million athletes could have gotten through that operation and been successful afterward.” It took three surgeons four hours to patch Brees’s shoulder back together. Of all the thousands of surgeries Andrews has performed, he says, “that was the No. 1 most memorable.”

So as the years passed, the story of the short signal-caller who conquered insurmountable odds—the kind of story sportswriters love to tell almost as much as fans love to ingest—morphed into folklore. Brees became the 6-foot, twice-injured savior who scrapped his way to football immortality. The little quarterback who could. But any narrative that centered on height and shoulder surgery went too far. It’s like we’re more proud of him for his greatness than we are transfixed by that greatness the way we are with, say, Brady and Rodgers and Manning. In other words: Brees’s path may have been unlikely. But the quarterback? Just great.

Come on. Brees threw for 90 TDs and almost 12,000 yards at Purdue. He won his seventh passing title in 2016, 11 years after he won his first. He owns five of the nine 5,000-yard-plus passing seasons in NFL history. More than half! Sure, Brady and Rodgers had their own origin struggles, but the focus of their stories evolved to center on their otherworldly gifts. Brees? Still the little guy with the big heart.

But consider the similarities. Like Rodgers, Brees is more athletic than he’s given credit for; he beat fellow Austin native Andy Roddick in junior tennis and played AAU ball with Chris Mihm. Brees, too, has a legendary memory, full of slights, and a long history of overcompetitiveness—broken Ping Pong paddles, long silences after wayward golf drives—that borders on unhealthy. Like Manning, he’s notorious for his preparation, whether spending an hour debating a single play in a game-plan meeting or overseeing every aspect of the itineraries of family vacations with the Fujitas. Like Brady, he’s learned under a Canton-bound football genius, and he’s dependent on a long-in-place team that cares for his body, obsessing over nutrition, stretching and muscle pliability.

And also like the Pats’ quarterback, who told New England brass years ago that drafting him in the sixth round was the best decision the organization ever made, Brees stared his Chargers offensive coordinator Brian Schottenheimer dead in the face in 2004, as San Diego weighed drafting Brees’s replacement, and said, “That would be the worst f------ mistake this organization ever makes.”

So what, exactly, makes Brees the underdog? What makes him any more human than those others? Short answer: nothing, unless we cling to a few inches of height. And “we’re talking frog hairs here,” says Tom House, the longtime throwing guru who has long worked closely with both Brees and Brady. “If [Brees] was doing this stuff by himself, it would just be absolutely amazing. [But] he’s been hiding in a crowd.”

Now, all these years and broken records later, Tomlinson posits a more accurate look back. Had Brees remained in San Diego for that 2006 season, when Tomlinson won league MVP and the Chargers went 14–2, he says they would have “probably gone undefeated” and won the Super Bowl. Not as plucky, lovable hustlers. But as an NFL powerhouse.

“He still hasn’t gotten the due he deserves,” says Tomlinson, now an NFL Network analyst. “We get enamored with size or appearance. Drew Brees is the most accurate quarterback in NFL history and he’s six feet.

“What’s the problem?”

Wendell Pierce was filming a TV show in Moscow when he made time to watch Brees break the all-time passing record. The quarterback means that much to the New Orleans–born actor. Pierce also remembers attending the NFC Championship Game in 2010 against the Vikings, and how an older gentleman in front of him just couldn’t bring himself to watch the overtime field goal attempt that might send the Saints to their first Super Bowl. Pierce grabbed the man’s head and physically turned it toward the field. “Goddammit, we’ve been waiting all these years!” he shouted. “You’re going to watch this!”

When Garrett Hartley’s 40-yarder drifted through the uprights, the two men hugged and danced and cried like children. “I never got to see Jesse Owens run,” says Pierce. “I never saw Joe Louis box. But, man, if it isn’t special to be alive and watch Drew Brees every Sunday.”

Cameron Jordan likes arguing with fans. “Just for fun,” he clarifies. The topic: Drew Brees is the single best quarterback in the history of the NFL. The numbers make a compelling case: 73,580 passing yards on 6,494 completions, with a 67.3% connection rate, all records. Then there’s his metronomic consistency: He last threw for fewer than 4,300 yards in 2005. (Let’s preempt your freakout. No one is calling Brees the GOAT. Just: His case is stronger than you might think.)

Fans arguing with Jordan inevitably bring up Brady’s five rings or Rodgers’s arm or Manning’s brain or Montana’s grace. Jordan will stick to the numbers. “Who’s had more passing seasons like Drew Brees?” he’ll ask. “I’ll wait.”

Jordan will reference an old Sport Science segment from 2009 that measured Brees’s accuracy throwing balls at a target. The QB released each one at a launch angle of almost exactly 6 degrees, and his passes traveled an average of 52 miles per hour, with almost 600 revolutions per minute—not as hard as Patrick Mahomes, but sharp enough to hit open receivers all over the field. Brees threw 10 balls from 20 yards and hit 10 bull’s-eyes—more accurate than most elite archers. “Who completes passes like Drew Brees?” Jordan asks. “I’ll wait.” Brees, he’ll note, is flirting with an 80% completion rate this season—that after setting an NFL record last year of 72%. He’s made 320-yard passing games his norm, turned pedestrian wideouts into household names and transformed the 10–1 Saints, again, into football’s scariest offense—all of which makes that whole underdog thing such a ridiculous sell.

“Facts,” says Jordan. “The only way that you underrate Drew is if you don’t count completion percentage, total yardage and touchdowns.”

Brees has won throwing deep and won throwing short. He’s won with the league’s 28th-best rushing attack, and he won 11 games last season with Alvin Kamara and Mark Ingram becoming the first running-back tandem in NFL history to each surpass 1,500 yards from scrimmage. What he hasn’t won is what Jordan is so fired up about. He’s never won an MVP award, not even after he broke Marino’s single-season passing mark in 2011, throwing for 5,476 yards. (The MVP, with 48 of 50 votes: Rodgers, who threw for 800 fewer yards but won one more regular-season game.)

House can explain as well as anyone why Brees deserves to be viewed in the same realm as his contemporaries. He believes Rodgers “is probably the most talented thrower in the history of the game,” followed by Brady and then Brees. Brady, he says, is the savant with computerlike recall, followed by Brees and then Rodgers. And Brees, he says, is the best at controlling the game—processing information, making split-second decisions—ahead of Brady and then Rodgers.

“He orders chaos as well as anybody I’ve ever seen,” says House. As part of Brees’s training, House affixes the QB with a band that measures brain activity, and whether Brees is dripping sweat or taking a water break, his readings hardly change. That he doesn’t look the part, like Brady, Manning or Rodgers, is beside the point. Ignore the dad camouflage. He throws and obsesses and prepares and cajoles and competes just like those others. Again: splitting frog hairs.

Instead of debating the merits of each quarterback, House proposes, we should kick up our feet and crack open a beer. He compares it to modern-day men’s tennis. It doesn’t get any better, might never be this good again. Brady is Roger Federer, the regal king with the most titles. Rodgers is Rafael Nadal, the artist whose very artistry makes him more susceptible to injury. And Brees is Novak Djokovic, the technician, the one whose greatness isn’t as readily apparent, who is sometimes overshadowed by shinier objects. Like the bouncy house.

“They all go about their brilliance in their own way,” House says. “We should just enjoy that we get to watch it.”

Last year someone sent Archie Manning a photo from an honors ceremony. Pictured: Marino, Brett Favre and Archie’s son Peyton, along with a caption noting the 200,000-plus passing yards accounted for in that one snapshot. But now, Archie points out, you could swap in Brees for Marino and that number would go up, past 215,000. That’s football today in a nutshell, he says: “If Patrick Mahomes plays into his 40s, he’ll have 100,000 yards.”

Records indeed fall. Peyton Manning sent his father a text message recently. There’s a kid at Peyton’s old high school, Isidore Newman, who broke his single-season passing record. “All my records!” he wrote. “They’re all gone!” In the NFL they fell to Brees, mostly. For now.

So it’s the first weekend in November. Louisiana is the center of the football universe. On Saturday, No. 1 Alabama will tango with No. 3 LSU in Baton Rouge. On Sunday the Saints welcome the 8–0 Rams. But first: Brees, sliding comfortably into dad mode, is “super pumped” and “really, really excited” for a series of flag football playoff games on Friday night at City Park in New Orleans.

There’s chaos on the sidelines—kids snacking on chicken fingers, moms discreetly pouring wine into cups, a deejay blasting Drake at max volume. . . . And Brees stands in the center of it all, assigning order to the mayhem, chomping gum like a young Pete Carroll.

His first- and second-graders win two playoff games with a power outage sandwiched in between. Dusk gives way to darkness. The lights come back on. Imagine what it must be like to stand on the opposite sideline, coaching your kids, only to look across and see the NFL’s chief record breaker holding that black binder.

Brees’s older team, the third- and fourth-graders, takes the field last. They fall behind, roar back to tie it up and just miss an extra point that would have settled the whole thing in regulation. For a second Brees flashes that thing that makes him Brees—arms splayed out, face twisted into another grimace. Then the Boilermakers lose in overtime and Brees gathers them in a huddle, telling them as they wipe tears from their eyes that they should be proud of their season.

Two days later Brees will throw four touchdowns, handing Sean McVay and company their first loss of the season. He’ll say afterward that he has no imminent plan to retire, no long-term vision after football beyond expanding his flag league and coaching his own kids. In all this, he’s not actively trying to change his story. But with the history he’s making and in the records he’s ignoring, the narrative surrounding Brees and his career is becoming more accurate.

Yes, the injury and the surgery and the recovery are still part of it. So is Katrina. But so are all the numbers, and the wins, and the performances that are, dare we say, superhuman. They’re the reason Bobby Hebert, the Saints quarterback turned broadcaster, wonders in all seriousness whether local officials will replace the city’s torn-down Robert E. Lee monument with a statue dedicated to the quarterback. Ruffins, Carville, Pierce—they’re all right. It’s time to see Brees the way they’ve long viewed him, regardless of height or appearance or false premises.

They know the real story, that of the genius-surgeon-robo-quarterback and the dad absorbed in flag football 48 hours before the season’s biggest game. That Brees can be both of those things at once doesn’t make him any less heroic than Brady, Manning or Rodgers. It just makes him Drew Brees, one of the greatest quarterbacks, if not the greatest, who ever lived.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.