Terrell Owens Isn’t Done Talking

To watch The Big Interview: Terrell Owens in its entirety, plus the rest of the The Big Interview series and more original SI programming, go to SI TV for a free seven-day trial.

This story appears in the Dec. 3, 2018, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

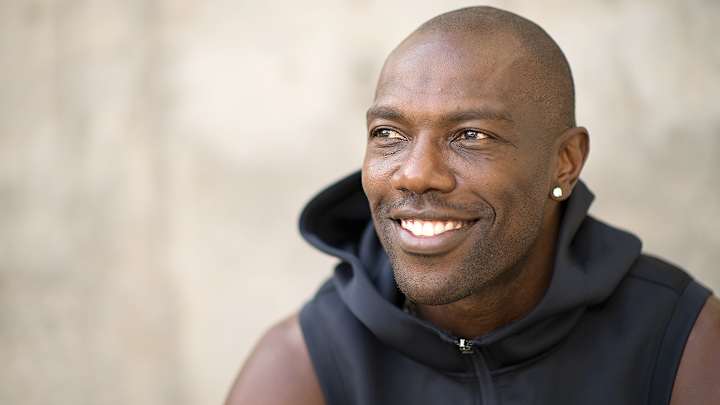

Terrell Owens wants to get away. He dreams about that sometimes, how freeing it might be to just . . . escape. Pack up, move to Australia, find a remote island, grow a long beard. “Like, to hell with everybody,” he says, laughing. “Start fresh.”

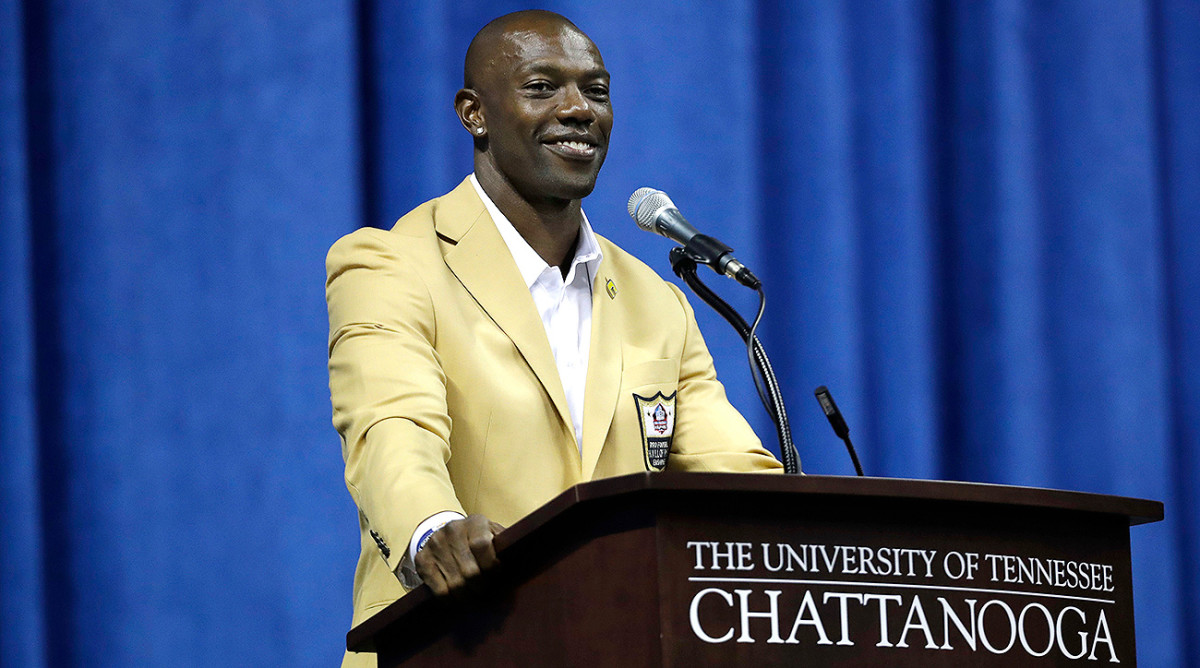

What’s stopping him? In a sense, the same things that have kept him daydreaming about disappearing. His “unfairly” sullied reputation. His beefs with writers and TV analysts and the organizers at the Pro Football Hall of Fame, even if he passed on his ceremony in Canton, Ohio, in August, preferring to fete himself at his alma mater, Tennessee at Chattanooga. Owens, at 44, must stay and fight and continue to address these things. He can’t leave, he insists, or “they” win. He can’t move on, or “they” win. In the case of T.O. vs. the Perception of T.O., he’s the last prosecutor left.

It all matters to him, the jokes and memes and character assassinations that others, he says, are spared: “Look at our President. He can go and say and do whatever he wants, and the majority of people like what he’s doing. They think that’s O.K. Those same people, they can like him and hate me? How?!”

Owens spits the question out as he steers a pickup truck through the Hollywood Hills on a jam-packed Monday in August. This afternoon he will run sand dunes, chug protein shakes, shop for workout gear, get treated by a chiropractor and squeeze in some pickup basketball in front of a royal audience. He’ll also try once more to explain how he ended up here, retired, ostensibly happy, at last a Hall of Famer—and yet, more than ever, intent on arguing for his reputation.

“Christmas with the Chipmunks” plays on the stereo as Owens navigates traffic as fluidly as he did secondaries. His skills, his numbers—second all-time in receiving yards (15,934), third in touchdowns (153)—require no defense. Yet T.O. feels the need to do battle. “What makes me angry?” he asks. “Why would you think I’m angry?” Well. . . . T.O. cuts off a reply. “As it pertains to me, that perception is not my reality,” he says. But. . . . “The perception is that I’m selfish, self-centered, egotistical, cocky, arrogant. That I’m the worst teammate in history.”

2019 NFL Team Needs, Part II: Cowboys, Patriots, Steelers and More

Owens has a few ideas about what might have created these perceptions, and he rattles them off from a notes file in his brain: 1) his division of locker rooms from San Francisco to Philadelphia during a five-team, 15-season odyssey of an NFL career; 2) his outspoken nature outside of those locker rooms; 3) his “harmless” touchdown celebrations; 4) even his playing on a broken right leg and torn ankle ligament in Super Bowl XXXIX, where he caught, incredibly, nine passes for 122 yards in the Eagles’ loss to the Patriots. Huh? Owens says his heroics in that game were framed as selfish, though a fact check suggests he contrived that framing himself. He looks at a performance for which he earned universal praise and still, somehow, perceives that he was slighted.

What matters, Owens says repeatedly, is how his story is presented. And he cites a fresh example to make his point. He wore his gold Hall of Fame blazer to church one day this summer. It was a favor to his pastor. But seemingly anyone who didn’t know that detail looked at this wardrobe choice and saw T.O.’s usual self-aggrandizement.

“I don’t get it,” he says. Owens has never been arrested, never jailed, never charged with a DUI. And he’s the one who voters kept out of their precious Hall for two years? Owens is faulted, he says, for his competitive nature, his individuality, his passion, his honesty. Those same Hall voters, Owens says, “let guys in with basically blood on their hands.” (He doesn’t go there, but consider: Ray Lewis, for one, was a fellow 2018 inductee, in his first year of eligibility.)

Owens’s reputation, he says, has slowed his postfootball progress, costing him jobs, sponsorships, another shot at the NFL . . . even dates. “Like a smear campaign,” he says. He points to a T-shirt deal he says he once had in place with Costco—a deal that was killed after those execs found out that this Terrell Owens was actually the Terrell Owens. “We don’t want anything to do with him,” he says his reps were told. (Costco declined to comment.) Same thing happened when Owens met a woman at a nail salon recently. They exchanged numbers and made plans for a date that Friday night. Later she texted Owens, bailing. She’d Googled him. “My friends,” she explained, “say you’re a bad person.”

All of which raises the question: Was anything Owens ever did really that bad? Well, no. Perhaps, though, he’s also missing the point, fighting this caricature with the same unfiltered angst that turned Terrell Owens into T.O. He admits he’s made mistakes, he’s human, he’s not perfect before adding “they” always say he’s crying victim.

Then he says, “I am a victim—to a certain extent.”

Terrell Owens sits on the concrete patio of a Los Angeles TV studio, having just scarfed a Chipotle chicken burrito. He’s trying to find the balance that has eluded him over the years in situations like this—the balance to stand up for himself without adding another controversy to his greatest-hits list, to attack his least-favorite perceptions without sounding bitter or delusional. It’s a reasonable goal, if not an attainable one.

He flashes back to the beginning. How his late grandmother Alice Black told him never to let things other people say “deter you from being who you are.” How he grew up in Alexander City, Ala., without any male guidance, learning at age 11 that his biological father actually lived across the street. How no one in his family ever said, “I love you.” And how all of those events hardened his exterior to mask the insecurities he buried deep and carried with him. Where did all those outbursts come from? Start there. He was, at heart, an outsider searching for acceptance. Still is.

He bloomed late, starring at UTC before the 49ers took him in the third round of the 1996 draft. His first few years were remarkably quiet; he sobbed after making a game-winning playoff catch against the Packers, but that was easy to get behind. Perceptions changed irrevocably, he says, in 2000. He can trace the shift to a single game, at Dallas, in September.

The 49ers were conducting their walk-through at Texas Stadium that Saturday when Owens found himself standing on the Cowboys’ famous midfield star. An idea occurred to him. And so when he scored the next afternoon he ran to the same spot, spread his arms and celebrated. He scored again and did the same thing, this time making it 41–17—a blowout, more offensive. Three Cowboys sprinted out to tackle him.

What happened next typifies Owens’s central issue—it’s the difference between how he viewed his own actions and how others saw them. He deemed the preening harmless. Anyone could have seen the controversy coming, but he was surprised. Even now, he can’t resist taking a shot at his coach back then, Steve Mariucci, who suspended him for a week. “He’s a phony,” Owens says, continuing a pattern of lashing out whenever he has felt betrayed. “The heartache he caused—I don’t have anything good to say about him.”

For Owens it’s pretty easy to explain away this incident, and all of those that followed. Oftentimes, it’s easy to see his side, too—to see the innocence in each misstep. He just doesn’t perceive the patterns, how each episode feeds off the previous. He knows that, no matter what he says, it will reverberate across social media. And yet, even though he wants to focus on how he has been wronged, and how much he has changed, he can’t help himself. He’s still the guy who lauds Jerry Rice on the TV studio patio and then wonders aloud how many touchdowns he might have scored himself if he’d been playing all those years with Joe Montana and Steve Young.

NFL Mock Draft 2.0: Nick Bosa to San Francisco, Quarterbacks to Tampa Bay and Denver

He answers questions for hours, seemingly without fear of consequence. If he were still playing, he would have knelt beside Colin Kaepernick, for starters. “I’m with Kap,” he says. “The President does a real good job of deflecting what the real issues are. You have owners stepping in, basically siding with the President. Some [players] feel betrayed.”

T.O. moves on to end zone celebrations and freedom of expression. The NFL of his days had yet to embrace his brand of individuality: grabbing pom-poms from a cheerleader or snagging a tub of popcorn from a fan. But he could never defend himself without the filter of those who covered him, the way that, say, Le’Veon Bell can in 2018, through social media. “I wish I played now,” he says. “I’d probably have a million followers. I’d be a trend-setter. One of those guys that fans really adored.”

Presentation. He hits that point again. For instance: On the call box at Owens’s condo in Beverly Hills he lists himself under HANDSOME. Is that really such a big deal? Was it really that big a deal when he conducted an interview while doing sit-ups in his driveway, in 2005? It is if you’re looking to demonstrate self-promotion. But Owens won’t meet his critics in the middle. He can’t ever cede that, in some instances, “they” might have a point.

Does he regret any of this? His feud with Eagles QB Donovan McNabb? The way he forced himself off a contending Philadelphia team? The sideline tantrums? The $150,000 in fines for excessive celebrations? How he insinuated (and later took back) that another former Niners teammate, quarterback Jeff Garcia, was gay? Owens doesn’t flinch. “I don’t regret anything,” he says. “As it relates to football: nothing. I don’t need to. I know who I am. I know who T.O. is.”

Does he regret anything in life? “Maybe my last girlfriend,” he says, smiling. “That didn’t work out.”

For Owens it’s not all about looking back. He’s trying to move forward. And the centerpiece of Operation: Reputation Reclamation hinged on that trip to Chattanooga, where he took underprivileged children on a shopping spree (and steered one kid toward a pair of “no‑show” socks), thanked his father (among others) at a private dinner on Friday night and then became the first Hall of Famer to induct himself. All signs of growth, in his mind.

“This just feels right,” he said more than once during his weekend in Chattanooga, hoping that “they” would see his alternate ceremony as groundbreaking and yet respectful, a shift from the T.O. me-first caricature. Not everyone took it that way. Many critics said the old receiver had again found a way to shine the spotlight only and brightly upon himself.

Owens had first returned to UTC’s campus three years earlier, for homecoming, and he’d felt love that weekend—love “like I never felt before.” That he kept coming back made perfect sense to his friends. Owens’s alma mater had given him the thing he craved most: acceptance.

Back in L.A., fighting traffic on the 405, he details his problems with Hall of Fame organizers and voters. In 2016, the first year he was eligible for induction, he traveled to San Francisco for Super Bowl 50 and did the typical rounds expected of a potential inductee: the NFL Network interview, the luncheon for nominees. “Everybody was congratulating me,” he says. Afterward, Owens went back to his hotel room and waited for a Hall official to knock on his door and tell him the good news. The knock came, but the news was not what he expected.

Owens couldn’t believe Marvin Harrison was going to be inducted and he wasn’t. “My stats are far better than his,” he says of the Colts receiver. “I’m thinking, What is it with me?”

He felt singled out and unfairly maligned. He heard players turned analysts say they wouldn’t want to play with him, that he wasn’t a good teammate. Whether or not they were on to something, they’d never been his teammate. He points to someone like Derrick Deese, a frequent defender of Owens’s who suited up with both Owens and Rice in San Francisco, and who says both men gave similar, fiery halftime speeches that were interpreted by teammates and staff in opposite ways. Rice, the thinking went, cared so much, was so competitive; he badly wanted to win. T.O., saying the same things, cared about only T.O.

VRENTAS: NFL and Social Justice—What Teams and Players Are Doing in Their Communities

When Owens went to Houston in 2017, before Super Bowl LI, and again failed to get the necessary votes, he resolved, without telling anyone, that if he were ever inducted, he wouldn’t go to Canton. “It was just pure disrespect, period,” Owens says of the second vote. “It was personal.”

He goes so far as to say he believes he was finally voted into the Hall last February only because Randy Moss, another receiver with a reputation for petulance, was going in. Voters, he says, “felt pressure” because Moss was going in on his first year of eligibility. “They were giving me an olive branch.”

The closest Owens came to extending one back: He did go to Canton, in March. He toured the Hall of Fame and listened to president David Baker explain the history. But that meeting only aggravated Owens’s grievances. As he saw it, the Hall had failed its job in giving writers full control of the nomination process.

Later, in Chattanooga, he themed his acceptance speech “This is for you” and, at one point, told those in attendance to stand up if they’d ever felt isolated. Or misunderstood. Or had “been lied on, mischaracterized.” By the end, the audience was on its feet. Everyone but the sportswriters. T.O.’s haters “wanted me to lash out,” he says. “I knew they wanted [the speech] to be a flop. But it wasn’t. I showed my true self.”

At his after-party Owens danced to Bobby Brown’s “My Prerogative” and played table tennis for hours, performing the way he once did on the field: pointing at opponents and calling them punks, waving goodbye after each win. For a less divisive athlete this might be described as the ultimate show of competitiveness.

Those closest to Owens say he’s the happiest he’s been in years. He celebrated in Chattanooga with his four children and 160 friends and family members. He says he heard from potential future Hall of Famers, many of whom were emboldened by Owens’s choice not to attend his own ceremony. He recounts running into retired NBA forward Horace Grant, who pulled the old receiver aside and told him how proud he was. “That validated everything,” says Owens. “Don’t tell me what I’m going to miss. Miss? You can’t miss something you never experienced.” His voice rises. Hall officials “should be ashamed of themselves.” He can’t help himself.

Beyond the love and respect Owens believes he’s earned, there’s one other thing he wants: a comeback. That’s why he’s running sand dunes on a random Monday in August like it’s 2006 again. He starts slowly, powering past sweaty civilians on a 60-degree slope until, of course, his shirt is off and his body glistens with sweat.

Dunes like these, he says, helped save his career back around 2003, when his hamstrings screamed and he played through a groin injury. Owens changed his whole routine back then, adding resistance bands, cutting carbs, chugging water. On his frequent trips to Waffle House he ordered the same thing: 10 egg whites and 10 tomato slices.

So why wasn’t this the story of T.O.’s career, the way the TB12 Method is for Tom Brady? Owens makes clear: Brady stands alone at his position. But thriving at 41? “For me, it’s nothing impressive,” he says. “If Tom can come out with a documentary [about] defying the odds, why can’t I be one of those guys too?” But he knows the answer. “[Brady] can curse his coaches and teammates out, and he’s looked at like a leader—like his guys need that.”

It would take something close to a miracle, though, for Owens to become the first Hall of Famer to get back on the field. And he knows this. He knows that he last played professionally six years ago with the Allen Wranglers of the Indoor Football League, that he then failed a tryout with the Seahawks . . . and that he is not viewed, by any reasonable measure, as someone who would be a positive locker room influence. Instead he has flirted with the CFL, to no end.

Are they all missing something? This summer Owens twice ran a 4.4-second 40-yard dash, which he posted on Instagram. And he worked out with the likes of Giants receivers Odell Beckham Jr. and Sterling Shepard. E.J. Manuel, an NFL quarterback of five years, was throwing balls one afternoon with that group, and for whatever it’s worth, he says Owens was “probably the best out of all them.”

Owens is not particularly hopeful, though. This is his reality: He believes a return to football would change perceptions—but those very perceptions complicate any comeback hopes. He clings to the dream anyway. “If the opportunity arises,” he says, “I would entertain it.” (A return would also help recoup some of the $80 million in career earnings he’s squandered, including the minifortune that a financial adviser “misappropriated” and poured into risky investments.)

Over the years Owens has acted, rapped and modeled; he’s played pitchman and written a children’s book; he did reality TV shows and talk shows and game shows; he even tried his hand as a weatherman. Nothing stuck. Now he’s trying out a more unexpected role: as speed coach and mentor for a few professional athletes. He runs sprints in L.A. with Nashville Predators defenseman P.K. Subban. (“I can’t stand next to you with my shirt off,” Subban says at one workout.) Then there’s Falcons wideout Julio Jones, with whom Owens ran dunes and traded route tips this summer—all of which is said to have made Atlanta brass uneasy. In Jones, Owens sees himself: tall, fast, freakishly athletic. “It’s crazy that he only had four touchdowns last year,” he says. “That just shows you how underutilized he is.” And there it is, Owens summarized: He makes a reasonable point and pokes at the Falcons. Even when he’s trying to do right, it’s complicated.

He says he’s trying, at least. Trying to be less reactive, more proactive. Trying to listen, take advice and change his most self-destructive patterns. Trying to be a better father to his four children than his own dad was to him, all while dealing with four different mothers, three of whom chastised him on Dr. Phil in 2012.

On this particular night, Owens is heading to a pickup basketball game at JEM Community Center in Beverly Hills—a game in which both of LeBron James’s sons are playing. When the King himself stops by to watch, Owens runs over and they exchange pounds. “Congratulations,” James tells him.

T.O.’s team wins one game, then two, then five. He’s thumping his chest, throwing down dunks, missing three-pointers, arguing foul calls. At one point he jaws with Maverick Carter, James’s best friend and business partner, and while their back-and-forth isn’t anything out of the ordinary, it also seems indicative of Owens’s bigger picture. Carter is all over Hollywood, producing TV shows and documentaries; he’s in charge of the very kinds of projects Owens says he’s interested in. The wideout was always a natural actor; he played T.O. for years and boasts a long list of credits. (“IMDB me,” he says with a straight face.) So wouldn’t part of him want to play nice with Carter, to see what opportunities might arise? But he can’t help himself. They’re still arguing as Carter leaves, calling Owens an old man.

T.O. just laughs, caught between the perceptions he wants to change and the restraint it will take to change them. Carter, Hall of Fame voters, TV analysts—they can all think what they want. He has his rebuttals ready.

Owens turns back to the court. He’s looking for another game.