Jeff Fisher Is More Than Your 7–9 Jokes

Jeff Fisher is careening down the side of a very steep hill on his ATV in the middle of the Tennessee woods. I’m sitting on the back, holding onto the machine for dear life. He’s probably only going about fifteen miles per hour, but that feels pretty fast when you’re rolling down a muddy path about four feet wide, ducking to avoid low-hanging tree branches and heading straight for a sizable stream. The 20 foot-wide body of water we’re hurtling towards is one of two creeks that intersect on Fisher’s farm about 20 miles outside of Nashville.

“Feet up, Char!” Fisher yells. The tires and footbed plunge in three feet of water, so I do as I’m told and lift my legs off of the four-wheeler’s floor to avoid getting soaked. Fisher plows through and rumbles up the bank on the other side. A hunk of Copenhagen chewing tobacco is lodged between Fisher’s teeth and lower lip. He leans off the side of the ATV and spits, then looks back at me and launches into a story. All day he’s been telling me about players he’s kept in touch with, about parachuting out of a plane onto a practice field to surprise his team, about the rare fish he caught in Mexico, about his friendship with the late Bears great Walter Payton.

“It’s nice telling you my stories,” he says. “No one wants to hear my stories anymore. There’s a book in here somewhere, maybe. I wanted to wait until I was finished. Maybe I am finished.”

Eight NFL head coaches lost their jobs after the 2018 season, and there are currently two openings left. A few years ago—say, 2014—if Fisher weren’t with a team, his name would have been come up when general managers were thinking of who to hire to lead their teams. Even as recently as last year, it was reported that Fisher was interested in a handful of head-coach openings. But this year is different; franchises are looking for young offensive gurus, hoping to copy the success that the Los Angeles Rams have seen with the 32-year-old Sean McVay, the head coach they hired after firing Fisher midseason in 2016. The 60-year-old Fisher has lots of experience, but his mediocre season records have become a running joke among football fans.

BREER: In Kliff Kingsbury, the Cardinals Think They’ve Found Their Sean McVay

Fisher adjusts his backwards camo baseball hat and revs the engine, lurching forward up a hill as steep as the one he just shot down. He’s showing me all 300 acres of his farm, which he wants to start renting out as a wedding venue. There were rumors that Fisher had a 9,000 square-foot cabin in the hills outside Nashville, but the truth is that everyone was off by a zero: It’s 900. If he rents the property out for weddings, he’ll have to put up a tent.

Fisher has largely disappeared from the public sphere in the last two years. As you watch the players he once coached who are now in the playoffs—Rams QB Jared Goff, Rams RB Todd Gurley, Eagles QB Nick Foles—you might think to yourself, “What’s Jeff Fisher up to?” Well, he’s driving ATVs through the woods, but he’s mostly hunting and fishing in Tennessee and Montana, traveling to Alaska and Argentina to hunt and fish more, and consulting for the new league Alliance of American Football. He knows he’s become a punch line. He heard Booger McFarland say on SportsCenter, “Shame on you, Jeff Fisher, because you had America thinking Jared Goff was a bust.” He’s heard your jokes about his 7–9 and 8–8 seasons, his .512 career record, about Aug. 8 being known as “Jeff Fisher Day”. He knows you use numbers to make fun of him, and he believes there’s a story behind them that you don’t see.

“You want to know if I’m sitting here waiting for my phone to ring, to have an NFL team call me?” Fisher asked. “Maybe I’ll be hunting and fishing the rest of my life. I’ve made my peace with it. But yeah, I’d love to coach again. I miss the players. I just want to get back to the players. I go back to what Bum Phillips said. ‘There are two kinds of coaches: Those who got fired and those who are going to get fired.’ You’re all going to get fired at some point. Not all, but 99%. It’s rare for a player or a coach to walk away on his own terms.”

But Fisher hopes to one day get another chance to try.

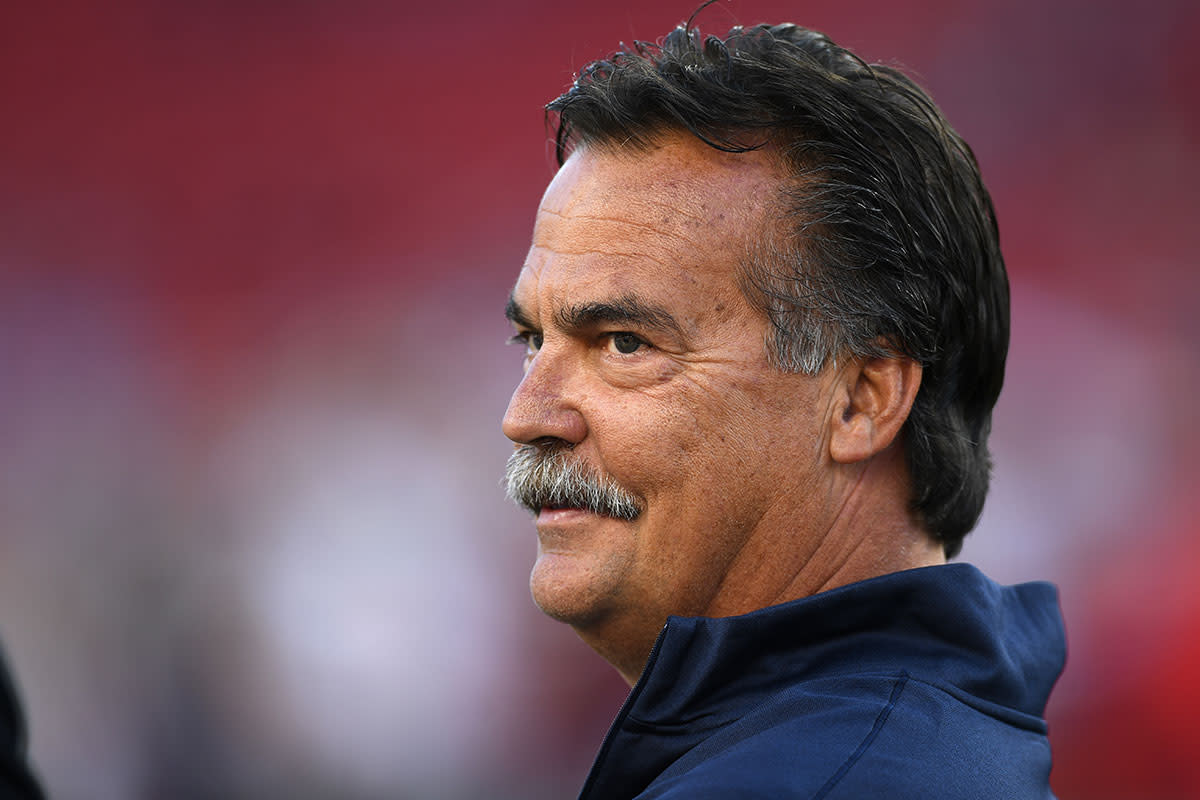

It’s 9:30 a.m. on Jan. 3, and Fisher is driving out to his farm in his huge black Chevy Silverado. He’s wearing a sporty Patagonia hoodie, down vest and jeans that fit well. He’s been taking better care of himself since he got fired; he gave up drinking a year ago—even though he still has a huge collection of red wine—and lost 30 pounds. He still has his signature mustache, and there’s a pair of reading glasses hanging around his neck, the kind with magnets between the nose bridge so he can easily pull them on and off. Raiders coach Jon Gruden wears them, too. Fisher says he’s the one who told Gruden about them.

Dirk, a six-month-old reddish Golden Retriever, wiggles in the backseat. Fisher picked him up from a breeder in Wyoming and sat with the dog for about half an hour in the front seat before he took him home, the two of them just staring at each other. Fisher doesn’t really know why he named him Dirk.

“I just looked at him and I thought, ‘Man, he looks like a Dirk,’” Fisher says, spitting tobacco into an empty coffee cup. He’s gotten healthier, yes, but the multiple tins of Copenhagen in his center console show a vice that remains.

He asks if people call me Char, and I tell him some do. “Okay, Char,” he says. He gives off a Big Lebowski vibe, an easy familiarity extends to everyone he encounters; servers at restaurants, the baristas at Starbucks, the guy fixing the tires on his son’s truck.

Fisher pulls up to the wrought-iron gate that sits at the top of the driveway. He squeezes the truck through, waving to his friend Jody who manages the farm, and parks the huge truck by the front porch of his tiny cabin. He enjoys helping people, figuring out what they need, giving it to them. He recently flew back to Montana for a day to take his parents to a wedding, which was outside in the cold, because he didn’t want them slipping on the ice. He once suggested that one of his players, Joe Barksdale, take up guitar; two years later, Barksdale sent Fisher two pictures, one of his daughter and one of his album cover. When Fisher’s neighbor evicted Jody from the house he lived in on the property, Fisher bought the land back with the house on it. Jody lives there again.

JONES: Speed of the Kingsbury hire raises eyebrows, questions

“I loved playing for Jeff,” says Eddie George, a former Titans running back. “He’s the consummate players coach. He gave us range and freedom to be men, but held us accountable inside the locker room to get our job done. He knew how to coach the person, not just the player. And it was more like he was really interested in our lives, our families lives, what made us tick. He knew how to inspire, mentor, nourish and cultivate guys. He’s a people’s person for sure.”

Keith Bulluck, a linebacker for the Titans from 2000-09, agrees. “Depending on who you were, he would handle things differently. He treated Eddie differently than Frank, and Frank differently than Steve, you know? He just had a good gauge on his players' personalities and what not, that made him an effective coach by knowing his players. Not just as what they could do on the field but who they are as a person.”

Fisher lets Dirk out of the truck and the dog takes off across the field. He walks into the house; it’s a small but intricately designed and carefully considered space made of pine from the property, with details like a deer carved into the back of the door. A rack of wine Fisher won’t drink anytime soon is fixed to the wall, and a hunting bow hangs off it. He likes bows more than rifles, because the hunt feels like an even match between him and the animal. There’s something spiritual about it.

“It’s not the shooting or the killing,” he says. “I’m not into that. But I enjoy the sport of getting close.”

Fisher’s a charming, fun guy to be around, which might be a part of why he’s, well, been around so long. Born in Culver City, Calif., Fisher went to USC on a football scholarship and was picked by the Bears in the seventh round of the 1981 NFL draft. He wasn’t a great player, but Chicago defensive coordinator Buddy Ryan recognized that Fisher had a mind for defense and asked him to serve as another set of eyes.

“It was a blast, I got to see [that defense] come together,” Fisher says. “I witnessed every moment of every game. … The ’85 Bears were the ’85 Bears. It was a bunch of tough, tough guys. I mean, I’ll say this: it was a bunch of badasses.”

After Chicago crushed New England in Super Bowl XX, Fisher took a box of beer from the party in the hotel and shipped it back to Chicago. He was selling software on his one day off; he made more money slinging floppy disks than he did playing in the NFL, even when you factor in his Super Bowl bonus. So he wasn’t about to pass up free booze. When he got home and unpacked it, he realized the brand was Dos Equis. XX. Super Bowl 20.

Ryan was offered the head-coaching job in Philadelphia after the Bears’ championship and he wanted Fisher to coach the defensive backs, despite the fact that Fisher had one year left on his contract with Chicago. According to Fisher, Ryan wouldn’t take no for an answer. “[Ryan] goes, ‘You aren’t going to try to play again, are you? … Talk to your fiancé and tell her you’re going to get into coaching because you can’t freakin’ play anymore. You’re not any good.’”

Fisher was promoted to the Eagles’ defensive coordinator in 1988, and he coached for the Rams and the 49ers before the Houston Oilers announced they were hiring him midseason to be their new head coach in 1994.

KAHLER: Matt LaFleur’s success in Green Bay will be tied to Aaron Rodgers

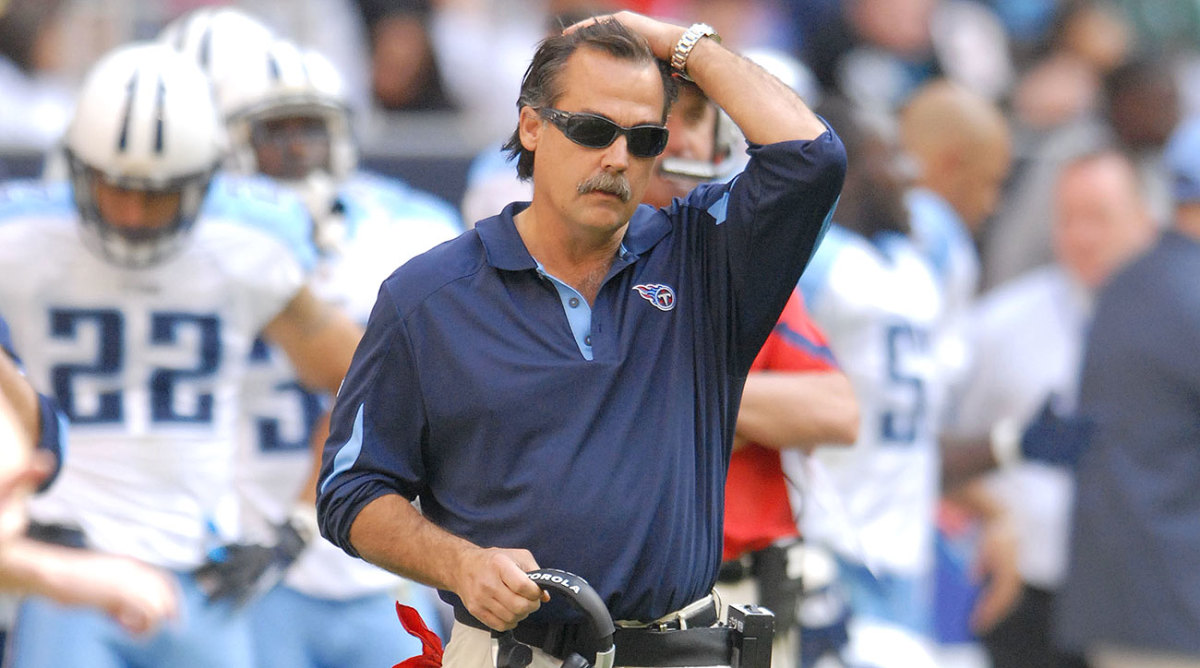

A year later, Oilers owner Bud Adams announced he was moving the team to Nashville for the 1998 season. It would be the first of two moves Fisher would oversee as head coach, and it subjected the team to a handful of nomad seasons, during which they played in Memphis and at Vanderbilt. Fisher says the year in Memphis,—which is two-and-a-half hours from Nashville, where the players practiced and lived—was like playing 16 road games. The team went 8–8 both seasons.

“The single worst thing you can have for winning and losing is distractions,” Fisher says. “Moving is a distraction. I kept preaching we have to keep the players first. In Houston we had an 800 number on the wall and told players when we were leaving, we said ‘Call the mover, he’ll get you there.’ Players were like, where’s camp? And we didn’t know yet, so we just had to tell them to move to Nashville. But we’re gonna play in Memphis. Players would be like, ‘How far is Memphis from Nashville?’ And we’d say ‘…never mind.’”

Once the team finally got into Adelphia Coliseum (which is now Nissan Stadium) Fisher started to cook. In 1999 the Titans, led by QB Steve McNair, came a yard short of winning Super Bowl XXXIV against the Rams.

“I have eight bottles of [the 1985 Dos Equis] left,” Fisher says. “That have survived move after move after move. I’ve been saving those to consume after I won a Super Bowl. So those eight bottles are lucky, cause they got about a yard away from being opened. I came a yard short. And I would not have gone for two. I would not have potentially robbed my team or taken a Super Bowl championship away from them because of a decision that I made. I felt like the Rams were absolutely done on defense and we would win the game in overtime, so I would’ve gone for an extra point. But I came a yard short.”

Fisher says everyone thinks he was fired, but he left Tennessee voluntarily. The Titans front office confirms his story: with one year left on Fisher’s contract and a lot of big decisions to make, it made more sense for both sides to walk away. In 2012 Fisher took the head-coaching job in St. Louis because he liked the owner, Stan Kroenke, and the promising quarterback Sam Bradford. It seemed like a great set up, but Fisher had no idea what challenges he was about to face.

After going 7-8-1 in his first year as head coach in St. Louis, Fisher lost his QB when Bradford tore his ACL in Week 7 of the 2013 season. In a cruel twist of fate, Bradford re-tore his ACL in the ’14 preseason. Then Kroenke announced that he was moving the team to Los Angeles. Fisher says he had a hard time holding onto coaches and hiring new ones with a huge change looming over the franchise. And having once dealt with the distractions, logistics, and complications that come with relocating a franchise, he didn’t blame them.

“The Raiders are … in for an experience. And don’t call me,” he says with a laugh when talking about Oakland’s impending move to Las Vegas. “You know, I’ll help you Jon [Gruden], I offered to help you, but I’ve been through that before.” He turns to me. “I mean, have you moved and relocated?

“Yeah,” I say, “It’s miserable.”

“It’s miserable, OK. Well have 150 people who work for you doing the same thing. And when they have problems, they come to you. Or plan it for all of them. Good luck, Jon Gruden.”

ORR: Bruce Arians Could Turn the Buccaneers Around Quickly

Fisher traded up to draft Goff with the No. 1 pick in 2016. He says he initially didn’t make Goff the starter so the rookie could adjust to the NFL, but his decision to start Case Keenum at quarterback instead drew plenty of criticism. After a 3–1 start that season, things began to fall apart until, after a particularly embarrassing loss to Atlanta, the team sat 4-9. Rams COO and EVP Kevin Demoff (who declined to comment for this story) told Fisher they were going in a different direction, which surprised the head coach—he had an idea he’d be fired but he thought he’d finish out the season.

Fisher tears up describing how he watched the bus pull away from the stadium on a Wednesday as the Rams set off to play Seattle before he packed up his office and left. “It’s a tough memory,” Fisher says, collecting himself. “Rejection is hard.”

“I think it’s really disrespectful in terms of what people are saying about him in terms of being the losing-est coach,” says George. “You flip that statistic on its ear, he’s only a couple wins away from being one of the top ten winningest coaches. Compare him to a Jon Gruden. You know, it’s the same thing. It’s just a matter of perspective—the only thing about Jeff is he fell a yard shy of tying for the Super Bowl and probably would’ve won it.”

The problem is that Fisher didn’t win it, and he’s tied with Dan Reeves for the most losses by a head coach. He and Gruden do have similar records. But Gruden has a Super Bowl and Fisher came a yard short. So Gruden has a coaching job, and Jeff Fisher has become synonymous with seven and nine.

“I think the 7–9 thing came from my comments on Hard Knocks when I was pissed at the team,” Fisher says. “I mean, that’s fine. I know that 7–9 or 8–8, that’s not good enough. I’m not a social media person, but how many positive comments do you see under anything that happens anymore? But you choose to get into this business, you know what comes along with it. I could read every little thing people write about me online, but I’d rather listen to Don Henley on the radio.”

Fisher is a numbers guy; ten years later, he still remembers the phone number that George called him from when he found out McNair had been murdered in Nashville (Fisher says he thinks about and misses McNair everyday). Fisher can recall the exact number of yards one of his running backs rushed for when he coached the Tennessee Oilers. He knows the length of every fish he caught in Alaska and Mexico and Montana.

Numbers tell a story, but different people decode them in different ways. Sometimes the takeaway is obvious, but in Fisher’s case, you can decide what to see. You might view Fisher’s first season with the Rams as a laughable “Jeff Fisher Day” 8–8, but he views it an improvement over the 2–14 team he inherited. You might look at his St. Louis team that never got above .500, but Fisher sees one ACL tear, several lost coaches, and moving 150 people across state lines to an uncertain future. You might see the Rams’ 13–3 record under McVay as evidence that Fisher couldn’t get it done, but Fisher sees the No. 1 pick he drafted blossoming into the player he knew he’d be. You might laugh at Fisher’s career .512 average, but Fisher sees the two teams, five different cities and six different stadiums, and wonders how you expected him to do any better given the circumstances.

Many will think Fisher is making excuses or asking for opportunities he doesn’t deserve. Others might see his side. But he was a head coach in the NFL for over 20 years; no matter the results, he couldn’t have done it without being fiercely competitive. He had to have some level of blind faith in himself.

Fisher knows that 90% of the public perception of him is negative, but the only thing he can do to change that is get another job, win, and tip the scales in his favor so that there’s no debate as to how his story is told. A lasting legacy isn’t the only thing that’s driving Fisher, though. Yes, he wants to drink those ancient Dos Equis, but he genuinely does love taking care of people and misses working with players and a coaching staff. And to them, he’s much more than a one-dimensional Twitter joke.

“We all loved Coach Fish. A guy that looks out for players, and keeps it special, and takes all the sh** like he used to, and all of our struggles?” says Rodger Saffold, who played for Fisher in St. Louis and Los Angeles, and plays for McVay now. “You can’t do anything but fight for a guy like that.”

Gregg Williams, who was relieved of his duties as the Browns interim head coach on Wednesday, worked with Fisher in St. Louis and Los Angeles as his defensive coordinator in 2012 (Williams was suspended indefinitely that season for his role in the Saints’ Bountygate scandal) and from 2014-16. If Fisher were to get a head coaching offer, Williams would work for him as his defensive coordinator in a heartbeat.

“[Fisher] is the best I’ve ever been with on understanding all the different areas of football operations, on how coordinated they have to be to be able to win on a National Football League level,” Williams says. It’s not just about coaching, not just about players, not just about facilities. All those things have to go hand-in-hand, and he’s the best I’ve ever seen on understanding all of that.”

Fisher knows that people sarcastically call him the Quarterback Whisperer. He heard McFarland accuse him of ruining Goff during the broadcast of the high-scoring Chiefs-Rams game on Monday Night Football.

“When people say that I ‘ruin quarterbacks’?” Fisher says, doing air quotes with his hands. “I had a co-MVP in the National Football League as one of my quarterbacks. I had a rookie of the year as one of my quarterbacks. I had a really good quarterback when I took the job with the Rams who tore his ACL twice. ... And yes, I was deficient. I probably could’ve done a better job surrounding the quarterback with better people, better players, maybe better coaches. But it doesn’t mean to say that I’m a bad quarterback coach. I’m not a quarterback coach, I’m a head coach.”

That’s part of Fisher’s problem right now, given this coaching market: He’s not a quarterback coach. He holds up his success with the Titans and McNair, and his brief period of time where things worked with quarterback Vince Young before their relationship fell apart, as evidence that he can win. He points to his 10–0 start in Tennessee with journeyman Kerry Collins, as proof of what he can do.

“I wouldn’t say he ruins quarterbacks,” Saffold says. “But you know, he’s a defensive-minded coach, so you can only go as far as you can. But you never know what type of complication you’re going to get in a season, so I wouldn’t say he’s quarterback killer. It’s more about having the right combination of people around, the right combination of coaches.”

JONES: Evaluating Jameis Winston and Marcus Mariota, Four Years Later

With a number of NFL offenses performing at historic rates, there’s little patience when a team isn’t producing. GMs are afforded more slack, but coaches who don’t win are fired. Steve Wilkes only had one year to try to turn around a sinking ship in Arizona with a roster that Bruce Arians let deteriorate. Arians recently secured the Tampa Bay Buccaneers job, and the 39-year-old Kliff Kingsbury, the former USC offensive coordinator and Texas Tech head coach, is the new head coach in Arizona. Guys like Kingsbury, McVay and Matt Nagy, who took over a promising Bears roster from John Fox, are what teams want most.

“It doesn’t help that the Rams are successful now, because it’s a, ‘See, I told you so!’” George says. “You look at the Rams success now and you think, ‘What was Jeff Fisher doing?’ But they’re winning with his roster, the bulk of his guys he drafted. He knows how to build a team. We’ll see how it pans out down the line. But I think that Jeff’s a hell of a coach and I think he deserves an opportunity.”

Fisher wants one. He’s consulting for the Alliance of American Football, a new football league that will start up after the Super Bowl, but he turned down a job coaching one of the teams because he’s holding out hope he’ll get back into the NFL. When I ask him if a team’s reached out, he says, “maybe.” No NFL reporter has leaked his name yet. But he really thinks if he got a team with a quarterback and a good owner that he didn’t have to move, he could make something happen.

“I had a good run here in ‘99, in the stadium here, until 2010,” Fisher says. “When we got into a stadium and had a run. So you know, I stand behind my work.”

Fisher and I leave the farm and drive to the famous Loveless Café for a late lunch. The walls are plastered with famous people from Nashville—mostly country singers, but there are some Titans are up there.

“Are you on the wall?” I ask him as we walk in.

“I don’t know,” Fisher says. “I used to be. They might’ve taken me down.”

We approach the hostess. Fisher asks if the owner is there (he knows him), but she isn’t sure. She says she can check, but Fisher tells her not to worry about it. He asks how long it’ll be for a table, and she says about 35 minutes.

“Let’s go somewhere else,” he says to me. “The wait is too long.”

Fisher thanks her and we turn to leave. He looks at the wall one more time, where a picture of the Music City Miracle is hanging. Fisher points to it and starts telling me how his son Brandon was just 10 years old, jumping up and down on the sidelines, when that happened. Now Brandon has a son of his own and has coached for his dad.

As Fisher walks back to the car where Dirk is waiting, wagging his tail, he relives the play. Per usual, he knows all the numbers: how many yards, how many seconds, how many years ago. But there’s no way to quantify how much he misses the game.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.