It's Time for the NFL Game Face Hats of the 1990s to Make a Comeback

Does anyone else find it paradoxical that pro football is awash in baseball caps? NFL fans buy baseball caps featuring the logos of their favorite teams. NFL coaches wear baseball caps during practices and press conferences. And one of the league's most enduring clichés is that the backup quarterback stands on the sideline, holding a clipboard and wearing a baseball cap.

But why should a football league be promoting itself with baseball caps? What the NFL needs is its own distinctive form of headwear. Something more football-y. Something the league can call its own. Something fans can bond with. As it happens, the NFL had precisely such a product nearly 30 years ago. For some inexplicable reason, it flopped. But if you wait long enough, old ideas tend to seem fresh again, and the time has come to revive this one.

It's called Game Face.

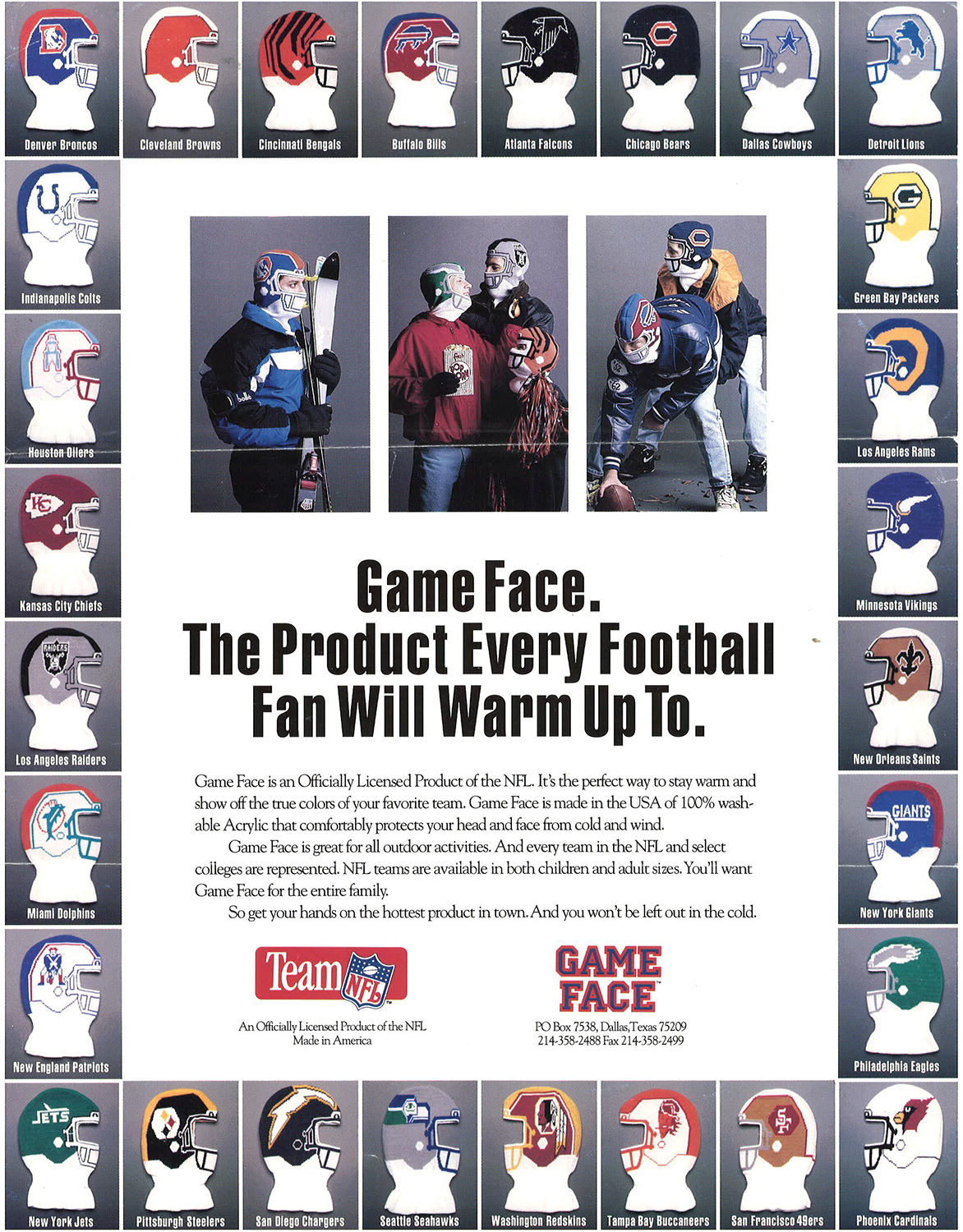

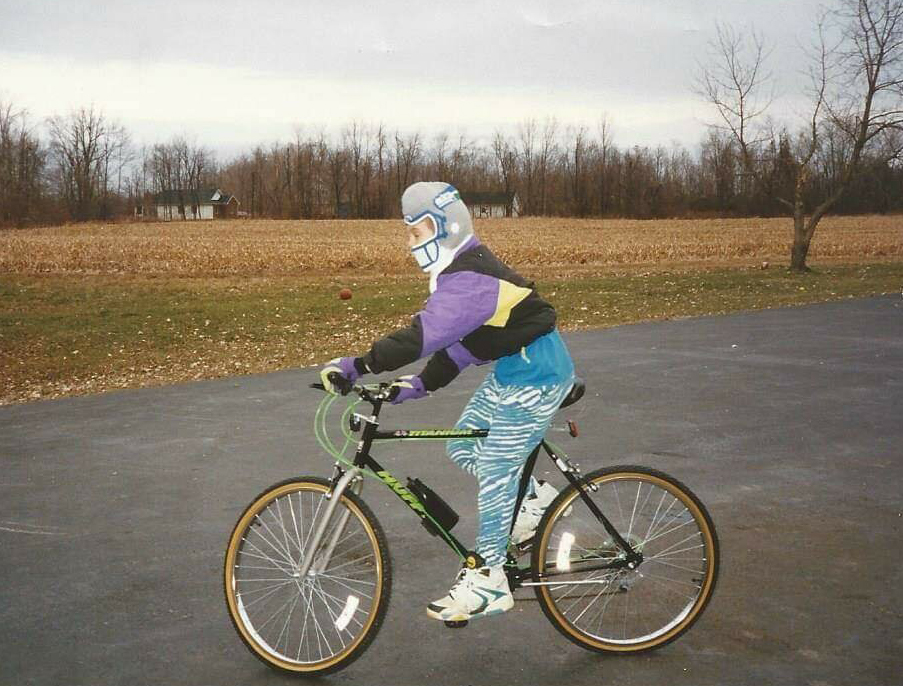

If you're too young to remember, or if you've just forgotten, Game Face was an early ’90s line of knit ski masks, each one designed to look like an NFL team helmet. If you put one of them on, you looked a little bit badass, a little bit silly, and a whole lot of NFL. It's such an absurdly simple concept that it's amazing nobody thought of it sooner. And the guy who eventually did think of it says the idea came to him—get this—in a dream.

“It was either 1988 or ’89,” says Drew Siegel, a 63-year-old attorney based in Dallas. “In the dream, I was basically behind some football players who were coming out of the tunnel. There was a player—he was a Cleveland Brown—and he was wearing a knit hat. Orange, with a white stripe down the middle. I only saw it from the back, because I was behind the players.”

When Siegel woke up, he couldn't get the dream—arguably the Browns' greatest contribution to the NFL over the past few generations—out of his head. He described the idea to a friend, who said it sounded like a winner. “So we hired a designer, just to draw up a sketch, which was essentially a ski mask that looks like a football helmet,” he recalls. “She drew it up, and that's how we got started.”

Siegel had no background in knitwear, headwear, or inventions, but everyone he told about Game Face agreed that it sounded like a million dollar idea. So he took his drawing (which he no longer has, unfortunately) to the NFL. Nowadays, the league's licensing division, NFL Properties, only works with large, established manufacturers, but 30 years ago they were still willing to do business with small, independent operators—like, say, an attorney from Dallas with an overactive sleeping imagination. They liked Siegel's idea, so they granted him a license and sent him to their primary knitting contractor at a mill in North Carolina. By 1990 or ’91—Siegel is no longer sure of the exact year—Game Face was available for sale in department stores and sporting goods shops across America.

As you'd expect for a ski mask, Game Face was most popular in the NFL's cold-weather markets, so the Bills and Bears hats racked up decent sales numbers. The Raiders version also sold well, presumably because the mask appealed to Raider Nation's outlaw mentality. Sometimes Siegel would be watching an NFL game on TV and see fans wearing his creation, which he says was “unbelievable, fantastic.”

But Siegel soon noticed a disturbing pattern: Although he had hired professional sales reps and distributors, overall consumer response was low. “Everyone who saw it said they loved it, but that didn't translate into sales,” he says. He tried various promotional partnerships—at one point there was a mail-in offer in conjunction with Hershey's candy bars, and there was talk of a stadium giveaway with the Bills—but nothing worked. The reality soon became evident: Game Face was a dud. Siegel estimates that he and his partners made about 35,000 hats but sold only a few thousand of them. By 1994, Game Face was done and Siegel went back to practicing law. He never dabbled in merchandising again.

“To this day, I don't know why we didn't sell more,” he says, sounding like a father who can't understand how his favorite kid, the one who everyone liked, somehow flunked out of school. “It was such a great idea, and we must have missed some key element, but I don't know what it was.” After a pause, he adds, “We always thought we'd get famous if someone would wear one in a bank robbery—that's what we were hoping for!—but nobody ever did.”

Granted, a marketing plan that relies heavily on a chance product placement during a felony may not be the ideal recipe for retail success. And sure, you can see why a ski mask might not sell so well in, say, Miami or New Orleans. (Although, really, wearing a ski mask on a hot day doesn’t seem all that outlandish for a league whose fans routinely go shirtless and body-painted in sub-freezing weather.)Still, it does seem a bit odd that Game Face never quite caught on. It's a clever product with a perfect name, built around the iconic imagery of NFL helmets — what's not to like? The NFL folks clearly thought the product was a winner; that's why they granted Siegel a license. (Unfortunately, a league spokesman said nobody who worked at NFL Properties in the early ’90s is still with the organization, so we can't pick their brains about Game Face.)

So what went wrong? Maybe it was just a case of bad timing. If Siegel had launched his product during the era of online ordering and social media, it's not hard to imagine that Game Face could have been a game-changer.

Interestingly, although Game Face's first act was short, the product has had a low-key but persistent afterlife. If Siegel's figures are accurate, about 30,000 of the hats went unsold, which explains why Game Faces routinely show up—often with their original tags—on eBay and in vintage clothing shops. Siegel still occasionally sees people wearing them at NFL games. A fan wearing one even appeared on a Sports Illustrated cover in 2012.

And while Game Face's consumer base was small, it appears to be passionate. Matthew Robins, a 39-year-old fan from the Chicago area, picked up a Bears Game Face as dead stock around 2000 and has worn it to countless games and tailgates. “If I go to a Bears game during the right time of year, it is still a must,” he says.

And Robins isn't the only one. “I still have my Chiefs Game Face, which I got for Christmas around 1992 as a kid growing up in Missouri,” says Marc Parker, a 38-year-old fan who now lives in Tampa. “If they brought it back with Bucs designs, I'd probably buy two—both the current and Bucco Bruce versions.”

And that begs the question: Is Game Face poised for a comeback?

If so, Siegel is ready. “I'd love to reinvent it, but with different fabric, as one of those things that the players wear under their helmets,” he says. That's actually a pretty astute idea—the lightweight fabric could solve the warm-weather problem, and printing the designs instead of knitting them would allow for more realistic depictions of the helmet designs, instead of 8-bit-style graphics of the original hats. Imagine the NFL Draft—or a sports bar, or a stadium—filled with fans wearing the modern, re-engineered Game Face 2.0!

Drew Siegel can already imagine it. He has mostly positive feelings about his Game Face experience, but the product's failure to catch on still gnaws at him, and he's itching to give it one more try.

“If you know someone who'd want to help me get back into the business, all they have to do is call me,” he says. Like they say in sports, dreams die hard.