'Welcome to the Brotherhood': Three Days in Rookie Camp With the Falcons

Rookie minicamp offers a coaching staff the first chance to see and work with its new players, before the veterans arrive for OTAs. The Falcons held theirs this past weekend and gave us an all-access look. (Editor’s note: The names of plays in this story have been changed to preserve the team’s confidentiality.)

DAY 1: THURSDAY

12:30 p.m. Dan Quinn’s Office

The office of the fifth-year Falcons coach is set off to the right at the main stairs in the team’s headquarters in Flowery Branch, Ga. From a desk outside the door, Sarah Hogan, Quinn’s right hand, points me inside There I find Quinn leaning against his standing desk, watching film. DMX and Snoop Dogg play in the background.

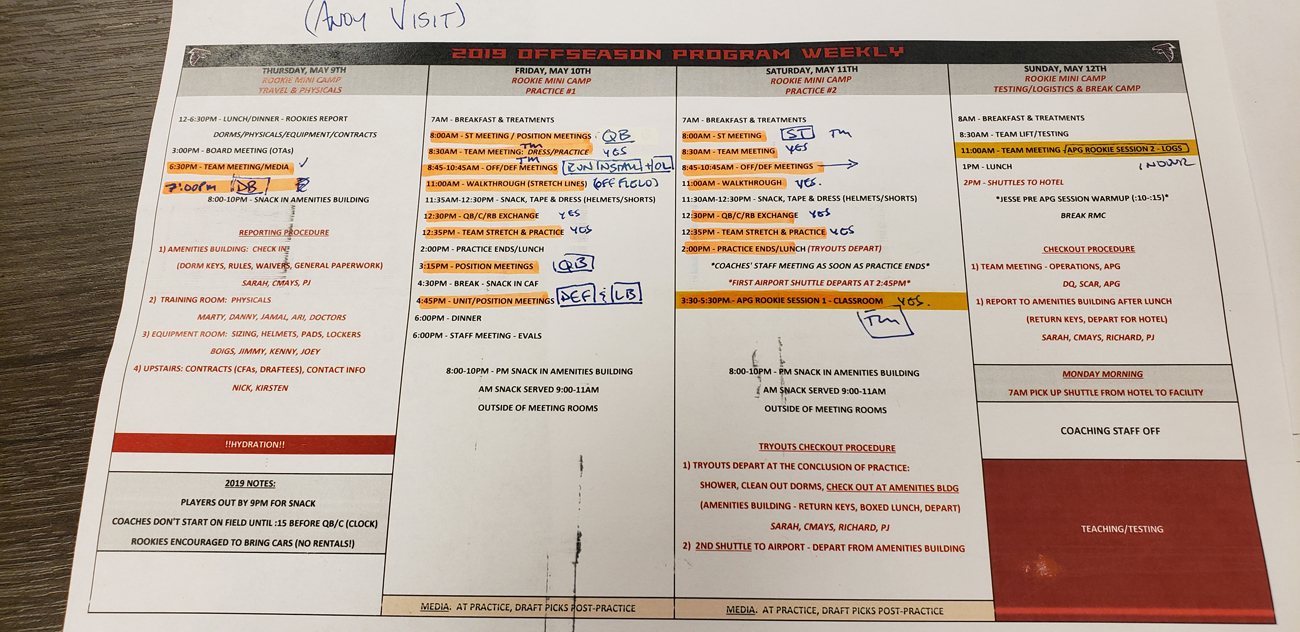

I’m here to learn everything that players learn at rookie minicamp. Quinn and I sit at his small conference table and he produces a copy of the camp’s three-day schedule. He has highlighted much of it with hand-written labels indicating where I’ll go and when. He wants my experience to be as diverse as possible. “I hope you don’t mind me planning out so much of it,” he says. Yep, he’s an NFL coach.

1:45 p.m. Amenities Building

An airport shuttle pulls up to the entrance of the building, which sits between two dorms down a small hill from the practice fields on the Falcons campus. Fifteen players file out, ranging from college free agents to tryout guys to first-round guard Chris Lindstrom. (The Boston College product’s fellow first-round offensive lineman, and Senior Bowl buddy, Kaleb McGary, is on a separate shuttle.) Lindstrom is pulling a large suitcase in one hand and whatever you call the next size up from “giant” suitcase in the other. He must be bringing some of his own football gear, right? Nope; all equipment will be issued to these guys in 30 minutes. Lindstrom is just settling in for a four-week stretch of minicamps and OTAs.

Players get quick medical checkups—boilerplate paperwork, blood pressure, etc.—right there in the amenities building. All are wearing athletic gear, except for Lindstrom (tan work jeans and Timberland boots) and one exceptionally eager hopeful dressed like he’s going to the office.

2:10 p.m. Equipment Room

The players walk through the main building’s halls in uncomfortable silence; nobody knows each other yet. They pass a sign posted on the women’s restroom: “Women’s only restroom, all players please use men’s room.”

The equipment room, which is adjacent to the locker room, has every NFL and major college helmet on display. Space-efficient floor-to-ceiling shelves that open and close at the turn of a wheel—as if forming a room-sized accordion—hold every piece of equipment imaginable. Many schools have sent over the specs for their players. Lindstrom is fitted with a temporary helmet; in a few days Riddell will come in and perform a 3D scan of his head for a permanent helmet. Earlier a test was performed on Lindstrom’s foot to help determine his best shoe. All drafted players and college free agents get such treatment. Lindstrom also tries on his gloves, which you wouldn’t think is worth mentioning except that the process is entertainingly slow. The gloves need broken-in. Encouragingly, though, the highly touted rookie gets the second glove on much quicker than the first.

6:30 p.m. First Team Meeting

Rap music blares even after all 62 players—seven draft picks, 16 rookie free agents, a handful of practice squad players still eligible for rookie camp, and the rest tryout guys—and 20 assistant coaches have taken their seats. Dozens from the front office and administrative staff stand in the back. We’re in the main meeting room. Quinn enters, the rap inadvertently creating a walk-up music effect. “Welcome to the Brotherhood,” he says. And then he jumps right in. “ Let’s go around, introduce yourself and share one thing about yourself. I’ll start. I’m Dan Quinn and I’m one of six kids in my family.”

The players share; any tidbits that are not outright innocuous elicit reactions. To express satisfaction, coaches knock on the table, while many players—or just the same few over and over, it’s hard to tell—say “oooohh sh--” to show they’re impressed.

Quinn runs through a few slides, introducing the team’s three pillars: Ball; Battle; Brotherhood.

And then the club’s rules:

1. Protect the team

2. No complaining, no excuses

3. Be early

Much of the meeting is dedicated to media training. New P.R. director David Bassity’s PowerPoint begins with this phrase: What question do you have for my answer? In other words, Bassity says, “You control the interview.” Quinn, with assistant head coach/wide receivers coach Raheem Morris playing reporter, demonstrates. His blatant deflections elicit giggles, but his delivery is polished and pure.

Before all this, however, there was a basketball shootout, which the Falcons do before most team meetings. A hoop sits on the side wall up front. Quinn calls up one player from the offense, fifth-round RB Qadree Ollison, and one from defense, fourth-round DL John Cominsky. It’s essentially a large pop-a-shot contest, with players and coaches from the loser’s side subject to 15 pushups. The first-rounders, Lindstrom and McGary, volunteer to rebound, which might be the most taxing thing they ever do as Falcons, as neither Ollison or Cominsky appear ever to have held a round ball. Ollison makes two shots—a triumph over physics given his motion and release. Cominsky makes zero, with several of the 18-foot jumpers looking more like passes to the rebounder. At the buzzer he raises both middle fingers to the crowd, proactively combatting the inevitable jeers. In the back of the room, one staffer, in disgust and bewilderment, says, to no one in particular, “that was bad.”

7:15 p.m. Defensive Backs Meeting

After a few minutes of player-by-player and coach-by-coach introduction and ice-breakers, it’s time to get down to business. Defensive passing game coordinator Jerome Henderson hands out thick binders, and the football portion of this weekend begins. In the room are 10 defensive backs, plus DBs coach Doug Mallory, assistant Chad Walker and former Chiefs defensive coordinator Bob Sutton, who recently arrived as a senior assistant.

The players are introduced to the Falcons’ base coverage and some of its siblings. Everything starts with understanding the key terms:

The side where the tight end aligns is called the Nub side. The opposite side is the Flex side.

The passing strength is determined by the wide receivers. The side with the most wide receivers is strong, the side with the fewest wide receivers is weak.

Some coverages are set to the big and small side of the field. If the ball is spotted on the right hash, that leaves more field space to the left, making that the “big” side of the field.

A major component of Atlanta’s scheme is a safety rotating down into the box. Often this dictates coverage responsibilities for the linebackers and defensive backs. A Ralph call describes a safety rotating down to the defense’s right; Linda is a rotation down to the defense’s left.

That alliterate correlation is no accident, and the concept applies to all of the Falcons’ play calls and communication. So, for example, the foundational Cover 3—which Quinn brought with him from Seattle—is called either Norway or Finland. The coverage is set to the tight end. So when the call is Norway, the strong safety is rotating down to the Nub side (i.e. the tight end side). Finland means he’s rotating to the Flex side (i.e. away from the tight end). A call like this named after a country means zone coverage. Man-to-man coverages are named after famous actors—Nicholson, Ferrell.

Henderson and the other coaches take the rookies through PowerPoint slides and pieces of film to explain it all. “These calls must be communicated boldly,” Henderson implores. He doesn’t mean just in the huddle. Since a tight end’s location dictates whether the zone call is Norway or Finland, when a tight end goes in motion the rotated safety stays put and the call changes. Norway can become Finland. Everyone on the defense must register that.

And this is all just for Atlanta’s main coverage. Every coverage has myriad variations, several of which the DBs will learn tonight. Like the version where a free safety, instead of strong safety, rotates down. Rather than pertaining to where the tight end is, a free safety’s rotation depends on where the wide receivers are. Remember the “strong” and “weak” thing? A call that rotates the free safety down to the strong side (i.e. the side with the most wide receivers) is called Sudan. If he is to rotate to the weak side (which is rare), it’s Wales. These are still countries, indicating the coverage is still zone.

That’s for the base defense. There’s also the version for nickel, and that call is predicated on where the slot corner aligns. In their standard Cover 3 zone, the Falcons alwaysput their slot to the “big” side of the field (i.e. away from whatever hash the ball is spotted on). The Falcons call their nickel Cover 3 zone Belgium.

All of this is presented to the rookies in less than an hour. And once the zone coverages are established, the related man-to-man and “matchup zone” versions are introduced. A matchup zone is when the zone coverage basically becomes man-to-man later in the down (as long as the offense deploys a vertical route inside). These coveragesare named after foods—Noodle, Fudge. Hear a food in the play-call and a defender knows he might have to convert his zone coverage into man. The Falcons may incorporate more matchup zone in 2019, as offenses have concocted so many ways to exploit their foundational Cover 3 (which is the defensive foundation for several teams). Quinn likes to install some of his new stuff during rookie minicamp so that coaches can use the session, as he says, “to find any blind spots in the teaching process.”

Toward the end of the session, the blitz versions of the man-to-man and matchup zone coverages are installed. The blitzes are named after cartoons—Tiny Toons (the back is “to” the blitz side), Flintstones (the back is away “from” the blitz side)—and the calls are based not on where the tight end or wide receiver aligns, but rather, on where the running back aligns. That is, unless the call is “dotted,” which occurs when the formation tells the defense it might be a run, in which case it is based on where the tight end aligns.

Got it?

“Study this tonight,” Henderson tells the players as they file out just after 9:00.

DAY 2: FRIDAY

8:00 a.m. | Quarterbacks Meting

“Don’t sit in Matt Ryan’s chair, he’ll know,” says quarterbacks coach Greg Knapp. “Sit across the table in Matt Schaub’s.” Knapp is in the small QB meeting room working an overhead projector. He’s with the rookie camp’s two quarterbacks, free agent Eli Dunne of Northern Iowa and Virginia’s Kurt Benkert, who was on the practice squad last year but is eligible for this rookie camp because he was never part of the Falcons’ active 53-man roster. Players in minicamp learn their position, but a QB must learn everyone’s. So far it’s going well. Benkert knows the offense from last year. Dunne is picking it up smoothly. His knee bounces in ostensible nervous energy, but he answers each of Knapp’s affable questions correctly. “That guy on‘Jeopardy’ has nothing on you,” Knapp says.

8:30 a.m. | Team Meeting

Quinn kicks this session off with another basketball shootout. Yesterday, receiver Shawn Bane introduced himself as the best basketball player on the team. So now he’s shooting for the offense. But first, edge rusher TreCrawford shoots for the defense. Crawford’s first attempt hits the low ceiling, leading to a cacophony of heckles—which die quickly as he hits the next five shots. When Bane steps up and drills his first attempt, Morris, the receiverscoach, jumps up and puts both arms in the air in triumphant expectation. By Bane’s third miss, Morris’s arms are back by his sides, and two misses later the coach is back in his chair. Soon he’s doing pushups with the rest of the offense, as Bane made just one basket.

Quinn’s PowerPoint lays out today’s practice schedule and reminds the players that “how you do anything is how you do everything.” Quinn then expounds on tackling—one of his great passions. Minicamp is no pads and no contact, but Quinn’s tackling lessons are about angles and leverage, which can be drilled anytime. The key to Atlanta’s foundational Cover 3 is players rallying to the ball. If you can’t do that correctly, you won’t play.

There’s also a lecture about finishing plays aggressively; if you don’t go hard in drills, the guy you’re working against can’t go hard, and you both get screwed. Technique is also critical—Quinn also doesn’t want men finishing plays on the ground. This time of year it’s dangerous, and from football standpoint it’s often ineffective. The Falcons even discourage receivers from diving for the ball because the team wants to emphasize run-after-catch. Lastly, there’s a quick demonstration on appropriate uniform attire. One team employee comes dressed right , the other comes out wearing a jersey that’s been cut at the bottom as well several pieces of apparel that were not team-issued—including pointless elbow sleeves that Quinn argues no longer even look cool.

8:45 a.m. | Offensive Meeting

Former Titans coach Mike Mularkey, now Atlanta’s tight end coach, kicks off the meeting with a sermon about running to and from practice drills. Throughout this meeting and others, Falcons coaches place heavy emphasis on seamlessly executing drills. Practices are short, and it’s imperative to maximize the number of reps. (“That’s one or two reps we lose,” Quinn says almost every time a player is caught doing anything the least bit inefficient.)

Mularkey then turns things over to offensive line coach Chris Morgan, who’s installing the base run plays. Morgan’s overarching message is that it takes 11 players to run the ball. He shows several clips, including one from 2016 of Matt Ryan pretending to run a QB keeper after executing a handoff. The ploy freezes Khalil Mack, removing him from the run defense. “You guys remember Mack?” Morgan deadpans. “Used to play for the Raiders.”

Today’s run plays are Willow, Spike and Thunder. Willow is an outside zone run away from the tight end. Spike is outside zone but to the tight end side, with a fullback leading the way. Thunder is a straight downhill run behind multiple double-team blocks.

It’s a quick presentation, as the offense breaks into groups to install the bread-and-butter run plays in fine detail.

9:00 a.m. | Offensive Line Meeting

The session begins with two of the camp’s 10 offensive linemen standing at the front of the room telling a joke. The first joke is so-so, the other is delightfully raunchy. The mood now lightened, Morgan digs in, flipping the lights on and off as he jumps between instructive monologues and supporting pieces of film. The 11th-year O-line coach (fifth year with the Falcons) brightens when the first-round picks, Lindstrom and McGary, ask smart questions. Questions are catnip to Morgan, and if he’s not fielding any, he’s firing them out.

“How about you, you have any questions,” he asks, addressing a player not by name but by school.

“Uh, no, they were all answered earlier this morning,” the player says.

“Every one of them, huh,” Morgan mutters, pacing the front of the room. He calls on other players individually, leaving them with nowhere to hide. Morgan is gruff but approachable—the type of personality you naturally yearn to please.

After a quick review of Willow, Spike and Thunder, Morgan introduces their play-action versions, beginning with Meadow, which starts out looking like Willow but will pivot with a fake handoff and throw.

“This play-action stuff is everything in our offense,” Morgan says. “It only works if you are 100 percent committed to it. You as an O-line make it go. Meadow has to look, smell and feel like a run.”

In Meadow, the offensive linemen uniformly move one way before suddenly “settling” their blocks, pinning the defenders all on one side while the quarterback rolls out a few yards the other way. “At some point the defense will smell a rat,” Morgan says. And so it’s important the blockers settle at just the right time. But for just the right time to matter, you must first get the defense believing it’s a run.

“Watch Brandon Fusco,” Morgan instructs, playing film of last year’s starting right guard. Fusco can be seen driving the defensive tackle to his left before settling his block to pin the defender. The tendency is for a blocker to wrap his outside hand around the defender he’s pinning. But Fusco doesn’t do that. “He gets his hands in on the defensive tackle, which makes the run-blocking action look authentic.”

There’s another version of Meadow where the quarterback rolls not just a few yards, but clear outside the pocket. Since the QB in this case does not need a throwing platform from within the pocket, the offensive line can continue driving its blocks instead of settling. “You can sell run all the way to the friggin’ field numbers,” Morgan exclaims, adding that the offensive tackle’s aiming point for blocking on these keepers is “right at the defensive end’s face.” Morgan has a deliberate, dramatic way of speaking. When he describes the importance of the QB-center exchange drill that occurs before practice, you’re convinced Atlanta’s Super Bowl chances hinge on that exercise.

11:00 a.m. | Walkthrough

NFL walkthroughs typically go exactly like as the name suggests—unless it’s with a bunch of rookies trying to make the team. At the starting horn, the entire O-line group sprints to its station with the urgency of men fleeing a live grenade. Halfway there, they realize they’re going the wrong way and, clumsily, all 10 turn around and sprint back to where they just came from. Eventually everyone is situated, and it’s here where players start looking their part. The first-rounders, McGary and especially Lindstrom, exit their stances with a crisp burst. Some of the undrafted guys are visibly processing the calls. One even waits for the rest of the group to perform an action before coming out of his stance to copy them.

12:30 p.m. | Practice

Almost nothing on the field of play is said only once. “Let’s go, let’s go!” every coach exhorts at least a dozen times. “The play is 18-19 Willow! 18-19 Willow!” yells another. “Motion! Motion! Motion! We got motion. Ralph! Ralph! Ralph! Ralph! Ralph!” yell multiple defensive backs.

A lot happens at once in practice, especially during position group drills.

On the near side of Field 1, Raheem Morris is berating a wideout about the importance of getting lined up. On the far side of Field 1, a tailback trips on a carry, and nearly a half-dozen players, spotting an easy opportunity to score brownie points under Quinn’s Brotherhood mantra, hustle to help him up. On Field 2, Mallory, the secondary coach, mimics a pocket QB, explaining to a defensive back in a tone that’s somehow both patient and impatient, “I’m not going to throw the ball while I’m still dropping back.” Mallory stifles a chagrined chuckle and adds, “I have to set my feet first. Don’t make your move until then.”

On Field 3, Quinn is wearing giant padded arm shields and a backwards hat, working with players on pass-rush drills. This year he’s returning to his roots as a D-line coach and working hands-on with the edge defenders.

Near the end of practice, the receivers face the corners in a seven-on-seven sequence. The wideout Morris lit up earlier gets dominated on a play, and again Morris is in his ear. Defensive backs coach Jerome Henderson sees this and says he wants the next corner who’s rotating in to also go up against that wideout. Henderson is giving the wideoutanother shot. This time the receiver follows Morris’s instructions, working his release more patiently, and beats the corner. Morris beams. “See what I’m saying?! See what I’m saying!?”

“I want to go again,” the receiver quips. But before he’s told no, the closing airhorn sounds.

2:00 p.m. | Lunch

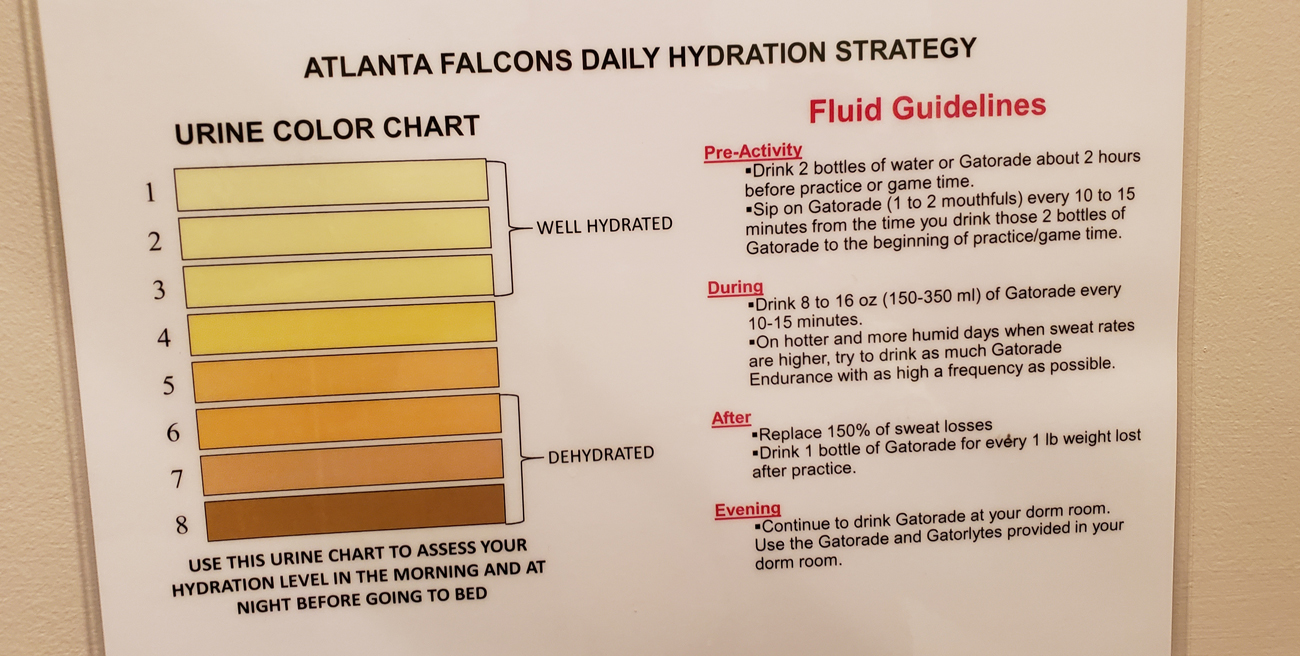

The food options are healthy and plentiful, and the players’ portions are enormous. Gatorade and bottled water are everywhere, with young trainers peddling the liquids. “Hydration” and all of its redeeming qualities are stressed more than anything else at camp. (Above some of the toilets is a chart that teaches players to monitor their hydration levels by examining the color of their urine.) The cafeteria is often busy, as there are scheduled meals at 7:00 a.m., 11:35, 2:00, 4:30 and 6:00. “This cafeteria is one of the best parts about my new job,” Bassity, the new P.R. director, is heard saying more than a few times.

2:45 p.m. | Thomas Dimitroff’s Office

The 12th-year GM’s domain is strangely bare when you walk in, but you soon understand why. On one of the three walls (the fourth is a window overlooking the practice field) is Dimitroff’s draft board, which is initially obscured by electronic blinds. The board is now empty, but Dimitroffis going through the digital version of his draft board on an 80-inch screen, which hangs next to the other 80-inch screen that he uses to watch film.

He’s viewing his drafted players’ practice closely and mostly liking what he sees. “Lindstrom here, it’ll be interesting to see him once the vets arrive,” he says, slowing down the video. “The vets will try to faze him. But hey, Lindstrom’s a tough Boston kid. I’m sure he’ll have a response.”

3:15 p.m. | Defensive Backs Room

“What do you run—what’s your 40 time,” secondary coach Jerome Henderson asks, pausing the film and turning to the player in question.

“4.4.”

“4 what?” Henderson says.

“4.4.”

“4 WHAT?”

Now suspecting something’s up, the player is unsure whether to answer again.

“That does not look like 4.4,” Henderson says, playing the film. “At 4.4 you should be catching that wide receiver.”

On another play, a slot corner follows a receiver in motion, even though the slot coverage that was installed last night—the only slot coverage so far—is set to the big side of the field, not to a player or to an offensive formation. The corner should have stayed to that big side. But on film a linebacker is seen telling him to follow the motion, and after a slight pause, he does.

“Don’t let someone wrongly tell you where to go,” Henderson says.

None of this stuff is said maliciously, and players in the DBs room are clearly comfortable voicing questions. Henderson opened the meeting by explaining that blunt corrections are all part of the process, and if coaches don’t issue them, then “none of us get better.”

There’s great focus on coverage technique, which was also emphasized in last night’s installation meeting. In the foundational coverages, Falcons outside corners play either Smack or Pony technique.

Smack is simply straight man-to-man technique. You line up across from the wideout and, as DBs coach Mallory puts it, “you own that son of a bitch.” Pony is tempo/bail technique—i.e. off-coverage. The corner plays with a cushion and reads multiple receivers, starting inside and working outside. He’s responsible for anything that enters his zone—the area from the sideline to two yards outside of the painted field numbers, clear to the back of the end zone (which is another way of saying “don’t let any receiver get deeper than you”).

To illustrate this, Henderson pauses the film when an outside corner is located directly alongside his receiver five yards downfield. Henderson explains that anytime a receiver is even with a corner five yards into a route, the corner loses. Because from there a corner must turn and sprint, becoming utterly vulnerable to a comeback route. And so, Henderson stresses, an outside corner must stay on top of a receiver at all times.

Ultimately, the Falcons want their coverages to induce short passes. Henderson rolls the film and immediately sees a pass to the flat. Nice … except the looming tackler closes poorly on the ball. “In this league, if you approach a tackle like this,” he says, slowing down the film, “with your weight up high like that, you’ll get a chest full of Grown Man.”

Minutes before the meeting concludes, Quinn pops in, his hat still backwards from practice. “Guys, we need more speed today,” the coach says. “Whatever speed you have, we need all of it.”

4:45 p.m. | Defensive Meeting

Tomorrow’s new plays will soon be introduced by linebackers coach Jeff Ulbrich. But first Quinn, after preaching about effort and getting into football shape, has an NFL rules emphasis to stress: “The biggest change in the NFL [when coming out of college] is pass interference. You guys had 15-yard penalties. Now it can be much, much more. A downfield DPI? That’s worse than punching someone. In the NFL, you punch someone, it’s 15 yards. But grab their jersey downfield and it can be, like we saw today on this play [he rolls more film], 28 yards.” DPIs, Quinn says, are not just about the defensive backs. Often the DB gets in a tough situation after someone up front fails to do his job. It’s all connected.

To further drive home the importance of clean defensive play, Quinn asks Bob Sutton to recite a stat. “In the NFL, only 1 percent of drives that start at the 20-yard line go for a touchdown without a defensive penalty or an explosive play occurring,” Sutton says. It’s quiet for a moment, and many players are wearing a Wow! REALLY? expression.

5:15 p.m. | Linebackers Meeting

“I’m not very bright, so I swear a lot to fill the void,” Ulbrich, the LBs coach, jokes. He played nine seasons with the 49ers, then joined the Seahawks’ coaching staff in 2010.He came over from Seattle with Quinn when the latter took the Falcons’ head coaching job in 2015.

“Today I saw a lot of looking and then running,” Ulbrich explains. “Forget that—run and figure it out while you run.” Ulbrich follows this point with an explicit speech about going hard, imploring his players to leave everything on the field. “For a lot of you, tomorrow will be your last football practice ever.” A heavy silence sweeps the room. “Go hard, have no regrets.”

Then Ulbrich turns on the film, and the next 30 minutes are a master class in fine detail. He notes, for example, that when covering a running back in man-to-man, a linebacker should play to the help of his free defender but not line up in a way that makes him dependent on that help. Because a free defender early in the down instinctively thinks about helping against wide receivers and tight ends, not a tailback.

Also on the topic of alignment, when the defensive line is executing a stunt or twist, a linebacker should just align in his exact location of coverage, not in his run gap, because the D-line’s movement will distort that gap.

Ulbrich has a back-and-forth with a player about whether a linebacker in coverage should match the running back’s steps or mirror the running back’s steps. If those seem strikingly similar, it’s because they are. “We’re saying the same thing,” Ulbrich admits, “but we need to actually say it the same way. Because in the heat of the moment, that’s when communication gets messy.”

Ulbrich’s four-man linebacker group studies a formation that calls for a coverage to be set based on a tight end. Not on a split-out fullback, Ulbrich stresses, because tight ends are the more dangerous receiving weapons.

It’s 5:58. In two minutes, the meeting will end, as will Day 2 of minicamp. “Rewrite your notes tonight,” Ulbrich tells his players. “Then get a few other guys and work through this stuff together.”

DAY 3: SATURDAY

8:00 a.m. | Special Teams Meeting

Coordinator Ben Kotwica couldn’t sleep last night, and so he turned on the Warriors-Rockets Game 6 around midnight, watching Steph Curry score all 33 of his points in the second half. That gives Kotwica a perfect avenue with which to illustrate today’s theme: killer instinct. Not that these players should need much motivating. They know their future in football hinges on their special teams prowess.

Kotwica then shows clips of the previous day’s best special teams plays. The receiver whom Raheem Morris was coaching hard stood out positively several times. For today, the focus is mainly kickoff coverage. Kotwica teaches the NFL’s alignment rule and coverage strategies. “And if you make a play like this,” he says, rolling film of Dolphins running back Kenyon Drake celebrating a big kickoff coverage hit, “you can run around and celebrate all you want—just don’t take your helmet off.”

8:30 a.m. | Team Meeting

In placeof a pop-a-shoot, today’s meeting begins with “Falcons Jeopardy.” A hastily photoshopped picture of Alex Trebek in a Falcons sports jacket appears on the projector screen. The game features just one question, and if any player answers it correctly, the coaches will do pushups.

A new slide comes up, a photo of a dreadlocked team employee. The question below it: What is this man’s name?

“Oh, that’s easy,” one coach mutters from the back. The players recognize the guy as the staffer who organized the equipment from drill to drill on Friday. But his name?

No one answers, and soon Quinn order the players to hit the floor.

Then he informs the players that this is Kenny Osuwah, assistant equipment manager. As the second part of the slide explains, Kenny also goes by “My G,” “Long Walk”and “Balls Are In Guy,” because he yells “balls are in” when a drill is complete and all the pigskins are accounted for.

“Kenny and all the equipment guys work with us,” Quinn says. “They’re not here to pick up after us.” Yesterday, after practice, Quinn took note of which players simply left their towels on the floor.

8:45 a.m. | Defensive Line Meeting

D-line coach Jess Simpson is apologizing to his group for having been absent the last two days. Simpson was recently hired from the University of Miami, and two days earlier his house there burnt down. Simpson and his wife were not home and no one was hurt, but everything they owned was destroyed.

Quinn pops in and calls me out of the room. “Jess just got here and doesn’t know about the story you’re working on, so I don’t want to throw him off,” Quinn explains. “Come into our room.”

“Our room” is the edge defenders room, which is run by Quinn and Aden Durde, a London native who earned a defensive assistant job in 2016 after serving as the head of football development for NFL UK. He’s gifted at explaining—with an accent—how the trees fit the forest and why things are done the way they are.

The Falcons recently installed conference tables in their position group rooms so that players can better collaborate. Quinn sits at the table with the edge defenders, chiming in every so often and getting up a few times to demonstrate techniques. The coolest technique: the long-arm lift move, where a defender gets his hand underneath a blocker’s extended arm and powers up through it. Quinn demonstrates that it only works if the defender grabs at the blocker’s elbow. Any lower on the arm and there’s not enough leverage. “We are going to be better at fundamentals than everyone else by a mile,” Quinn says matter-of-factly.

Besides pass rushing moves, the Falcons focus heavily on how to defend the run and related play-action bootlegs. Coaches teach what Quinn calls a “Pup” technique. You slide down the line scrimmage as an unblocked defender, removing that space between you and the other linemen, all the while staying square. When you see that the QB has the ball, you “pin” the hip of the widest blocker and get “up” the field, where you then look to get “everything,” by which Quinn means “the ball.”

There is also a tutorial on landmark zone coverage, since an edge defender in Atlanta’s scheme must drop back and cover the flats. The players are taught the linebackers’ coverage rules so they can better understand the logic and inherent stresses of their own coverage rules.

11:00 a.m. | Walkthrough

The communication today is livelier and more urgent than on Friday, when players had just learned the terminology. In a walkthrough, it’s defense on one side of the field, offense on the other. Which means defensive players, at times, must stand in as offensive players when formations are being reviewed. Quinn plays quarterback in the defensive walkthrough.

Shortly after that, Durde works off to the side with a few edge defenders, moving trash cans around to simulate offensive alignments. The defenders’ job is to call out his corresponding assignment.

“Why are you whispering,” Durde snaps at the players.

“Crossfire! Crossfire!” the players shout—the alert word for a possible tight end backside block.

“Bloody right,” Durde barks.

12:30 p.m. | Practice

The edge defenders work on angled pursuit tackles, emitting screams, gurgles and grunts as they do so. Today’s practice is indoors. Yesterday’s was supposed to be, as well, as meteorologists’ had forecast a “100 percent” chance of rain. But it wound up being sunny enough that some onlookers came away sunburned.

An onlooker can sense the pain in a player when he makes a mistake. Reps are still very limited, so everything is magnified. A fringe player’s chances could ride on just a handful of snaps. One presumably displeased player concludes a drill with an emphatic handclap and furious F-bomb. At the conclusion of practice some 20 minutes later, he does it again, just to sum everything up.

2:40 p.m. | Lunch

Quinn approaches a table of six players who are ignoring each other, faces buried in their devices. The coach gently suggests that they put away their cell phones. “Get to know your teammates,” he chides.

3:30 p.m. | Team-Building

The tryout players have left, to await a call from the Falcons if their services are needed. Remaining are the 16 college free agents and seven drafted players. They’ll spend this minicamp’s last two hours watching a lecture from the Acumen Performance Group, a private entity comprising retired Navy SEALs. The group has worked with the Falcons since 2016.

“You’ve been on a one-man team of your own these last four months, getting ready for the draft,” Quinn tells his players. “So now we’re focusing on full team-building.”

With that, APG’s founder, Bill Hart, takes the stage and shouts orders. “Everyone into the front rows! Move! Move! Move!”

For the next hour Hart speaks about what it means to have a killer instinct and to be a high-level performer. Then, the retired SEALs and players perform team-building exercises.

Exiting the room afterwards, at 5:37, right tackle KalebMcGary glimpses a window and notes with pleasant surprise that “it’s light outside”—an absurd observation given that sunset all week has been around 8:30 p.m.

McGary makes for the exit. He and the other rookies will be back on Monday, this time alongside the veterans. For rookie nerves, Quinn says, this weekend has been tough.“But Monday is way worse.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.