Arena Football's Influence on the NFL Is Growing

Omaha Beef players of a certain age remember the old Civic Auditorium, where true fans sat in the corner section behind the visitor’s bench.

They called it the Butcher’s Block, and everyone dressed in long white coats. It earned the arena the nickname “the Slaughterhouse,” one of a number of places on the indoor football circuit where you’d be better off not getting flipped over the padded wall and into a row of beer-toting spectators.

Because of the players’ close proximity to the field, it was often hard to ignore the trappings that are synonymous with gimmick-laden minor league sports. Fans hurling miniature footballs into a hot tub being dragged behind a pickup truck. Michael Jackson impersonators. Tackle football games between local mascots, including the puffy blow-up kind.

“I remember they had the dancers at half time, some big old guys, they called them the Rump Roasters,” former Beef quarterback (and current Packers head coach) Matt LaFleur said by phone, referring to the Beef’s unofficial dance team comprised of local men of all shapes and sizes performing choreographed routines.

But beyond the kitsch, there was something to be taken from the football experience, even if, to the naked eye, the game looked as foreign to the NFL fan as a rotund Nebraskan dancing to Revenge of the Nerds in jean shorts and a cutoff t-shirt. LaFleur is part of a growing segment of the NFL head coaching population with ties to professional indoor football, which, some of them say, has aided their rapid rise in an increasingly high-scoring brand of the NFL game. In some cases, nearly identical plays or concepts have been ripped straight from the eight-on-eight layout, where coaches have to be more adept at creating favorable matchups in tight spaces.

LaFleur (Omaha Beef, Billings Outlaws), Matt Nagy (New York Dragons, Carolina Cobras, Georgia Force, Columbus Destroyers), Sean Payton (Chicago Bruisers, Pittsburgh Gladiators) and Jay Gruden (Tampa Bay Storm, Orlando Predators, Nashville Kats) were all quarterbacks in either the Arena Football League or Indoor Football league, while others, like Sean McVay were direct disciples of coaches who had recently been plucked from their ranks. Some of those coaches, like Nagy, have added more staffers from the indoor circuit after taking over their own teams.

Those assuming that better access to plays and information merely broke down the barriers between NCAA football and the NFL game are missing a much larger phenomenon. Sampling is happening from everywhere, with coaches even pulling plays from a league that once had a team owned by Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley from KISS.

“Because the NFL is the highest level, there’s an inclination to think that the only good ideas come from there,” said McVay, who began working with Jay Gruden in the USFL the year after Gruden left the Arena Football League. “But if you talk to most coaches, they’d share the feeling that it’s a constant process to learn. No good idea is something you’d brush over.”

Shane Stafford remembers watching a Chiefs game in 2017 when, before the half, the offense lined up feigning a Hail Mary to one side with three wide receivers (Tyreek Hill and tight ends Travis Kelce and Demetrius Harris). A handful of Cowboys defenders had already lined up across the goal line in a deep prevent defense. Hill snapped off his route early, allowing the two tight ends to get out in front and block for him as if it were a screen pass. Hill got the ball at the Cowboys’ 40, with the wedge of defenders still 20 yards in front of him. Kelce, Harris and DeMarcus Robinson, a bigger-bodied wideout lined up opposite the trips formation, were in space shoving some of the lighter Cowboys defenders around.

For Hill, it had morphed into a punt return, a play he was already better at than most in the NFL. He ran around Orlando Scandrick, then cut up in the space vacated by middle linebacker Justin Durant. If he’d been touched at all on the play, it was by a shoelace.

“I’ve never seen that in my entire life,” CBS color analyst Tony Romo said from the broadcast booth, still stunned by the time-expiring touchdown.

Stafford, the current offensive coordinator of the AFL’s Atlantic City Blackjacks, had. Plenty of times. Having grown up not far from Nagy, then the Chiefs’ offensive coordinator, and having watched him throughout his arena and NFL career, it was obvious where the play had come from. Through his time as an assistant with the Tampa Bay Storm and Washington Valor, he’d called a version of it himself.

“That is a staple play in arena football when it comes to end of half, or when I need a big play during a game,” Stafford said. “You have two route runners plan on being blockers, so it looks like a pass play but it’s not.

“The outdoor game is turning into the arena league, just with eleven guys.”

Nagy is one of the most notorious samplers, forged through a potpourri of different offensive styles during his playing career at Delaware in a throwback option offense, then in the AFL before settling under Andy Reid’s watch, first in Philadelphia then Kansas City.

Longtime Reid assistant Brad Childress said that Nagy was known for pitching running plays that were rooted in legendary Blue Hens coach Tubby Raymond’s interpretation of the Wing-T. The play to Hill was just one of the many outside-the-box suggestions he’d made at a time when Kansas City’s offense was becoming one of the most modern—and copied—systems in the NFL.

“When you look at some of his jet sweep stuff, the misdirection dives, that’s really what it is,” Childress said, referring to Raymond and the Wing-T.

But Reid also remembers other pet projects from Nagy he’d have to swat down when compiling the call sheet that were culled from his days with the Georgia Force and New York Dragons.

“I kept him down on those arena plays,” Reid said, laughing. “He tried calling one on me one time and I was like hey, hey, hey, we gotta back that one off. But he’s got a couple of good arena plays. He doesn’t forget anything.”

Doug Plank, Nagy’s coach with the Force, and a long-time NFL safety whose jersey number became the namesake of Buddy Ryan’s “46” defense in Chicago, said that there are certain things coaches can’t understand without experience in arena football or any of the other indoor football leagues. Time management is more acute. As a coach or quarterback, you’re constantly operating with the mentality of a team that is either on the 20-yard line about to score, or defending the same scenario. Mentioning Nagy specifically, he said the intricacies of backfield misdirection have been studied and utilized longer.

There was also Nagy’s well-known fearlessness of using tackle eligible plays, which are also a staple in the position-versatile arena game. Teams indoors don’t use tight ends.

“Your tackles can catch passes, and I thought several times I saw the Bears take advantage of that this year,” Plank said. (The MMQB’s Kalyn Kahler wrote last season about Nagy’s Bears having fun with unusual players eligible, and one such touchdown can be seen here.)

In football circles, the game’s various spinoff leagues are addressed with a certain amount of romanticism because of what they meant to different people. Smaller leagues can provide a soft landing for those who weren’t ready to stop playing the game after college. Or a first job for people looking to crack into the insular world of football without the connections. For some current NFL coaches, it was low-fi, but it forced them to be creative and see possibilities in a game, often with freewheeling rules, in a chaotic environment. Designing or quarterbacking an offense was like building a house in a windstorm without power tools.

LaFleur said that that during his time with the Beef, they played in the National Indoor Football League, an arena tentacle that allowed defenses to play zone in an attempt to curb the astronomical scoring of the AFL. The problem? The field was still shortened and condensed. Every play felt like target practice.

Now, as a play caller and designer in the NFL, tight situations don’t feel as limiting. There’s always a way around.

“That game reminds me of everything in the red zone, because everything is so condensed, and in that league it was condensed wherever you were on the field,” LaFleur said. “Windows would open and close so quickly, you absolutely, 100 percent had to anticipate every throw.”

The Beef’s new home is a few miles down the road from the old Slaughterhouse at the Ralston Arena. The building sits just off Route 80, tucked behind a TCBY and a place called Ralston Keno, which advertises the biggest Keno payouts in the state.

The coach’s office is downstairs, a sparsely decorated room of red and white painted block with brown trim, that contains a desktop computer, a printer and two boxes of Special K cereal sitting on a shelf.

It might feel like the furthest place in the football universe from the NFL, but not for Beef head coach James Kerwin, who has seen the evolution at the game’s highest level running parallel to the developments and changes in indoor football.

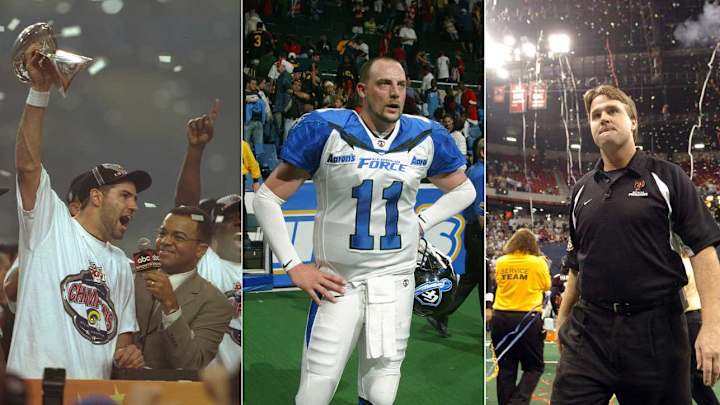

“A lot of it, offensively, it all goes back to that arena style, Kurt Warner. He’s the guy who made the first big break,” said Kerwin, who played with Jay Gruden on the arena circuit for a time. Warner famously went from ArenaBowls X and XI in 1996 and 1997 to Super Bowl XXXIV MVP in January 2000. “The Rams and that staff were ahead of the curve implementing the quick-release game.”

He pops the cap off a dry erase marker and begins to draw up a 2x1 formation typically utilized by his offense. There are two wideouts on the left and one on the right, plus three offensive linemen (no tackles or tight ends), a quarterback and a running back. Out of this set, Kerwin can bring the inside receiver on the left into a jet sweep, and run the outside receiver on a quick slant or stop route. The quarterback reads the defense on the handoff, and based on the look, decides whether to throw to the receiver or give the ball to the sweeping receiver. At its core, this is the now commonplace run/pass option concept that has helped NFL offenses throttle opposing defenses over the past two seasons.

In his time in arena and indoor ball, Kerwin has seen opposing coaches tackle one another. He’s seen coaches tackle opposing players. He saw a coach think the door to the penalty box-like bench was locked, only to lean through it and fall onto the field during live action. Ask any NFL coach about their time indoors and they’ll tell you about the beer can that was whipped at their head, or the popcorn they were doused in.

“But the one thing I want to say about this is, it’s not clown town,” Kerwin said. “There are a lot of professionals here. You just don’t hear about it because of the shenanigans.”

In a few minutes, he’ll meet with a quarterback, former Nebraska prospect Ryker Fyfe, about playing for the Beef. Fyfe is 25, recently out of school and hoping to stay in the game. He’s been talking to people about coaching opportunities. The football life beats the working life.

Kerwin’s sales pitch is extensive, touching on the local business opportunities, night practices and receiver talent.

And while Fyfe didn’t ask (he signed with the Beef and left after a week), Kerwin is prepared to tell anyone thinking of coaching at any level that this is a stop with benefits. Something that a few NFL coaches can attest to.

“It’s a great training ground for a coach under pressure,” he said.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.