How the Influence of Al Davis Shaped the Modern NFL

This story appears in the Aug. 26–Sept. 2, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

It had been a hell of a run for Matt Millen. The pugnacious linebacker played nine seasons for the Raiders, winning two Super Bowls, and he'd just been selected to the Pro Bowl. But here he was in 1989, in his early 30s, and he couldn't agree on a contract with team owner AL DAVIS, so Davis cut him, and Millen decamped to San Francisco where he joined the 49ers.

Not only were there no hard feelings, the owner and his former player stayed in touch, even in the immediate aftermath. And, inevitably, their conversations turned to football. The sport "was such a part of him, it was unavoidable," says Millen. "It's not like he was talking about his vacations or his golf game."

In part because Millen was playing for a competing team, and in part because Davis cut what might charitably be called a polarizing figure, Millen did not advertise that he still spoke regularly with his old boss (who didn't believe in saying goodbye and abruptly hung up when he'd said his piece). But talk they did, and during one late-night conversation Davis casually mentioned that he'd also long spoken to the man who'd just stepped down as Niners coach, Bill Walsh—which Millen at first thought odd. Wasn't Walsh, longtime coach from the team across the Bay, supposed to be the hated enemy?

The more Millen thought about it, though, the more sense it made. Why wouldn't a coach avail himself of one of the most agile and razored football minds he'd ever encountered? Why not seek Davis's insight on everything from formation to motivation?

In 1966, Walsh had been an assistant coach under Oakland's undeniably brilliant and undeniably combative general manager, Davis. The two men were close in age and shared a similar football belief system. Davis would move on to become the Raiders' majority owner, and Walsh would move on to a series of coaching jobs, his trajectory arcing ever upward, toward the Hall of Fame. In the early '80s, Walsh's teams were competing with Davis's for Lombardi Trophies—and yet the two men stayed in regular contact. Like Millen, Walsh didn't advertise it.

One time, in conversation, Davis casually mentioned to Walsh that he'd been speaking, too, with the 49ers' young owner, Eddie DeBartolo Jr., another eventual Hall of Famer—which Walsh, too, at first thought odd. Wasn't DeBartolo supposed to be a competitor, if not an enemy combatant? The more Walsh thought about it, though, the more sense it made. Why wouldn't an owner avail himself of one of the most agile and razored business minds he'd ever encountered? Why not seek the man's insight on everything from stadium financing to relocation?

Here was the perfect encapsulation of Al Davis. His football acumen was such that a player on a rival team would call him in the middle of the season to talk shop. His strategic acumen was such that the old coach of this same player's team would call during the season to talk X's and O's. His business acumen was such that this same coach's owner would call during the season to talk about how to master the universe. "He knew more about the NFL," says Millen, "than the NFL knew about itself."

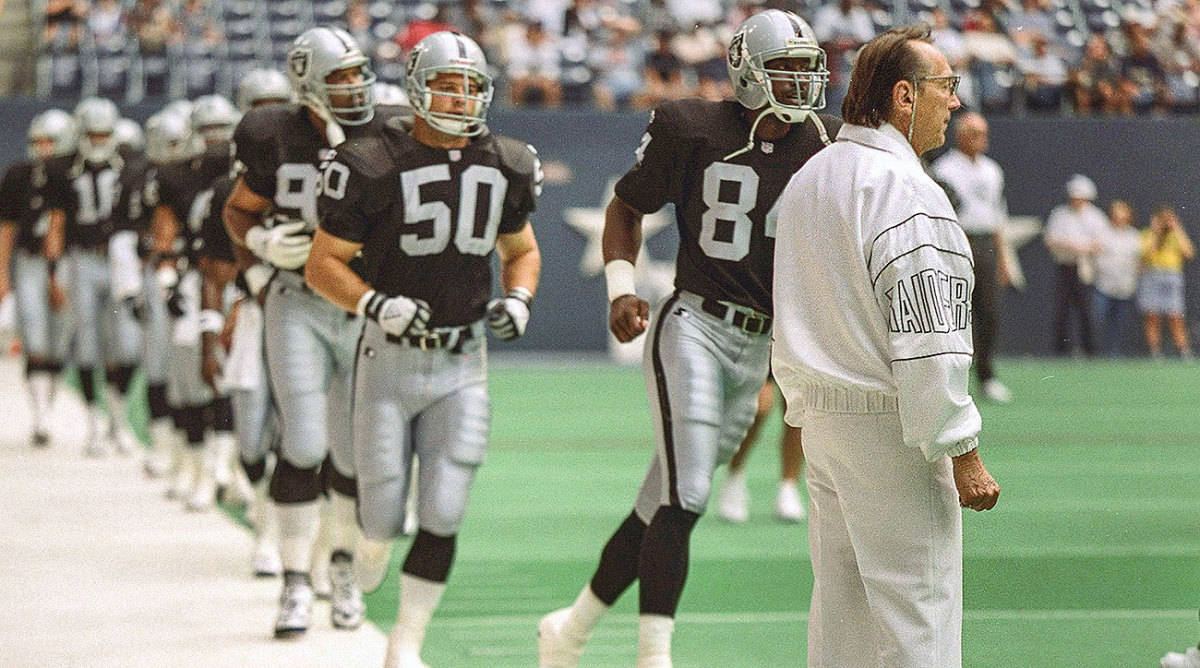

Today, if football fans under 40 know Al Davis at all, it's likely as the pompadoured persona non grata, decked out in gaudy jewelry, a white polyester tracksuit and a dismissive sneer. In his later years, when owners became as notorious and as prominent as star players, Davis was a sort of NFL anticelebrity, dressing, speaking and running his team as if trapped in another era. But there's an abiding irony to all this: No single figure has done more to shape the modern NFL.

Name a resonant issue, theme or innovation that pertains to pro football in 2019—offenses predicated on passing, teams moving markets, the NFL as the dominant American sport—and odds are good that Davis preordained it. Name a signature moment in league history and Davis, most likely, was there. Name a transformative figure and Davis, you can safely guess, had a connection.

Not unlike the NFL itself, more powerful and yet more maligned than any other league, Davis was—how to put this?—an acquired taste. Here was a man who thrived on conflict, almost as if incapable of functioning unless locked in a feud. With his players and coaches. With other owners. With his city. With the media. Above all, with the league itself. Even his loyalists today choose their words with a pained precision. "Difficult genius" is a phrase in common rotation. Some go further. "He was prickly, which can be shortened to 'prick,'" says Frank Hawkins, a top NFL exec in the '90s and '00s. "And I'm one of the ones who liked Al."

But Davis's influence is, unmistakably, everywhere, from Jerry Jones's micromanaging to Bill Belichick's shroud of secrecy. The spread offense that has Patrick Mahomes throwing almost 40 times a game? It bears Davis's fingerprints. The premium the league places on speed? Sean McVay and the trend toward younger coaches? Mel Kiper Jr. and the rise of the scouting industrial complex? Even, ironically, the Raiders' impending departure to Las Vegas? All traceable back to Davis.

The occasion of the league's 100th anniversary marks as good a time as any to consider—and reconsider—a man too often caricatured as the NFL's cartoon villain. Under the leather jacket and beneath the slicked-back hair there resided a mass of connective tissue. For all of Davis's bluster and bravado and brashness, through him we can braid together the league's past, present and even its future.

Long before Brooklyn became the hipster haven of today, it was something else entirely. In the 1940s, New York City's most populous borough was sliced into ethnic neighborhoods, and while each enclave was distinct, there were shared characteristics. Moods soared and sank based largely on the outcome of the latest Dodgers game. There was a push-pull between loyalty to the ethnicity of the neighborhood and loyalty to the United States. And there was a pulsing sense of possibility, a belief in a greater world beyond the Brooklyn Bridge.

In Flatbush, at Erasmus Hall High, then the largest public school in the country, a teenager named Al Davis grew fixated on how he could stand out from the area's other Jews (and Italians and Irishmen)—and, in turn, how he could get out. He wasn't the brightest kid, nor the most athletic, endowed as he was with a skinny, angular frame and average coordination. One point of differentiation: Davis's force of personality. "Al Davis," recalled Lawrence Kallenberg, a Brooklyn contemporary from a rival school, "made you notice him."

Simultaneously, a mile away, another Jewish striver, Woody Allen, was fashioning his own Brooklyn escape. Among other comedic characters, Allen would conceive of Leonard Zelig, a figure who could insinuate himself into any situation. Davis, likewise, moved easily among tribes, taking on characteristics of others and placing himself in great historical moments. Classmates would later be surprised to learn Davis wasn't the star QB, the valedictorian or the toughest kid at Erasmus Hall. He was just a Zelig who passed himself off that way.

In college, at Syracuse, Davis tried out for the baseball and basketball teams. Only after failing at those did he turn to football. And while he didn't actually play, he became obsessed with strategy, attending practices and taking notes, trying, in a sense, to hack the sport. Eventually he was chased off by coach Ben Schwartzwalder, convinced that Davis was spying for another team.

After graduation, in 1950, Davis interviewed for college coaching positions and, according to Mark Ribowsky's '91 biography Slick, showed up at Adelphi College representing himself as Syracuse football star George Davis. Al Davis was eventually put in charge of the freshman team.

After two years at Adelphi, Davis was conscripted into the Army. There, too, he coached football (and avoided being sent to Korea). He seized on the idea of compiling scouting information on his players and offered to sell his guides to NFL teams. Impressed by these guides and by his predictive powers, Baltimore Colts coach Weeb Ewbank (Hall of Fame class of '78) hired Davis as a freelance scout. (Anyone with a thing for symmetry will note that two decades later the head coach of the same organization would be the first to employ a young football savant named Bill Belichick, as a personal assistant.) Davis parlayed that gig into a full-time assistant position at the Citadel, where in true Zelig spirit he layered his Brooklyn accent with a Southern drawl and inflection.

By 1960, Davis had graduated from college to pro football, taking a job in the fledgling AFL as a receivers specialist for L.A. Chargers coach Sid Gillman. They made for an odd couple, Gillman and Davis. Gillman (Hall class of '83) was given to wearing bow ties, his pants pulled above his waist. He delivered his words in rapid, quick-burst cadences. Davis, in contrast, wore silver chains, a James Dean hairstyle and spoke leisurely, not unlike a young Christopher Walken.

Gillman and Davis, though, carved out plenty of common ground, from their Jewish upbringings to their almost devotional commitment to relentless strike-first-strike-often offense. Vince Lombardi, with his power sweeps, envisioned football at the time as a game of incremental gains. Neither Gillman nor Davis, though, had the patience for that. Their football axis was vertical, not horizontal. You stretch defenses. Put up points. Throw the ball early, often and down the damn field to players like Lance Alworth (class of '78), whom Davis presented a contract and signed for L.A. after racing onto the field as soon as Alworth finished his last college game, at Arkansas. If that worldview put Davis at odds with the traditionalists—among them, fellow Chargers assistant Chuck Noll (class of '93)—so be it.

As Davis explained his organizing principles to NFL Films: "I had to have certain philosophies that had to become part of what I was to do. We weren't looking for first downs. We didn't want to move the chains. We wanted touchdowns. We wanted the big play, the quick strike."

Up the California coast, meanwhile, the expansion Oakland Raiders went through three coaches in three years and in 1963 were looking for number 4—someone to right a team that had just gone 1--13. They turned to Davis. Wayne Valley, then the managing general partner of the team's ownership collective, later stated, "We needed someone who wanted to win so badly he would do anything. Everywhere I went, people told me what a son of a bitch Al Davis was. So I figured he must be doing something right."

When the Raiders first offered the job, Davis, then 33, declined, demanding a long-term deal. The team returned with a three-year proposal and he agreed, earning AFL coach of the year and leading Oakland to 10--4, which persists as one of the great turnarounds in football history.

By 1966 the NFL and the AFL were locked in a pitched battle, competing for players, the former trying to put the latter out of business. At the AFL's annual meeting that spring, commissioner Joe Foss resigned, likely before he was pushed out. Though Davis had no management experience at a league level, he did have that force of personality, and so he was summoned as the new commissioner. He was 36.

Pitted against his NFL counterpart, Davis versus commissioner Pete Rozelle made for great theater. A smiling extrovert, Rozelle (class of '85) came from a p.r. background, but he shared Davis's fondness for power. In '63 Rozelle had been named SPORTS ILLUSTRATED's Sportsman of the Year for "making vigorous decisions, not all of them popular, and proving that he could act independently of the owners who hired him."

Davis, too, approached his commissionership as something other than a figurehead. The NFL was not a competitor in a business dispute; it was an enemy in battle. And Davis was the general.

Valley, reading concern about this approach among AFL owners, tried to reframe Davis in the most benign light possible. "Al's his own boss, his own guy," he tried to reassure. "He doesn't wear any man's saddle." Davis himself was considerably less diplomatic. "Give us about three months to get organized," he said, "and we'll drop a bomb somewhere."

Which he did. Under Davis's militaristic leadership the AFL took the fighting to a new front. Beyond competing for rookies, the league would now try to poach its competitor's veterans. Oakland, for instance, signed Rams quarterback Roman Gabriel to a contract in 1966 that began immediately after his NFL deal expired. AFL teams began similar negotiations with NFL stars like Bears tight end Mike Ditka and 49ers QB John Brodie. This was an escalation to war.

In the end, two of the leagues' less hawkish execs, Lamar Hunt of the AFL's Chiefs and Tex Schramm of the NFL's Cowboys, met—often in secret, to avoid Davis's wrath—and discussed a path to peace. And in the summer of '66 the two outfits merged under the NFL banner. Rozelle would remain as commissioner; Davis would return to the Raiders.

By any accounting, the merger marked one of the pivotal hinge points in NFL history: The league was now unified, fortified and, for the first time, held a monopoly on the pro game. Davis's hardline aggression was a brilliant gambit that, purposefully or not, forced the compromise.

But the compromise also etched battle lines between Davis and Rozelle and, by extension, put Davis on the wrong side of NFL mythmakers. "Sometimes I will look through the history and it's like he's been written out," says Millen. "I'll be like, 'Where's Al?' It makes me sick. The merger? They [honor] Lamar Hunt. He brokered a deal. But that deal doesn't happen without Al Davis. Al forced them to do something."

Meanwhile, an idea that Davis (among others) championed, pitting the best AFL team against the best NFL team once each season, was taking hold. The AFL-NFL world championship game was first held on Jan. 15, 1967, with Lombardi's Packers beating the Chiefs in front of 61,946 fans at the L.A. Coliseum, far from a sellout. The following season, the Raiders represented the AFL, falling to Green Bay. By then the nickname for this game had stuck, and everyone began referring to it as the Super Bowl.

Back in Oakland, Davis found himself in the role best suited to his skill set: minority owner (after Valley carved out a 10% stake for him) and GM. For a man who always fashioned himself as smarter and savvier than his competitors—and his colleagues, for that matter—here was his chance to prove it. The self-styled maverick who actively reviled conventional wisdom could build his roster and accumulate power.

In his prime Davis was endowed with a sixth sense for assessing talent. Let everyone else scout USC, Oklahoma, all the college powerhouses. Davis dispatched his men—and often went himself—to backwaters like minuscule Maryland State, where he found bedrock tackle Art Shell (class of '89). He took special pleasure in finding unmined gems at historically black schools. In '68 he made Tennessee State's Eldridge Dickey the first black QB ever selected in the first round.

While this was all in keeping with Davis's sensibilities—his left-of-center political leaning, his esteem for the outsider and the underdog—it was also guided by free-market pragmatism. Why not draw your workforce from the largest labor pool possible? (In this way the trail-blazing nature of his drafting Dickey is undercut, in a sense, by the QB's immediate forced move to receiver.)

Bottom line: Davis approached his roster construction as broadly and as creatively as possible. Again and again he found discarded players and transformed them into stars. Long before Kurt Warner was discovered stocking grocery shelves, Davis was combing the equivalent of clearance aisles. His Raiders teams, as Ribowsky put it, were made up of "oddities and irregulars, factory seconds and chaingang escapees." Jim Plunkett, for one, had been cut by the 49ers before Davis transformed him into a Super Bowl QB. One of Plunkett's favorite targets, Todd Christensen, had been cut by four different teams before Davis thought otherwise. Defensive end John Matuszak, the top pick by the Houston Oilers in 1973, was a wild and woolly washout ... until Davis revived his career.

"He could always spot players who were undervalued,' says Hawkins. 'He was Billy Beane before Billy Beane."

Davis discounted conventional metrics and emphasized his own. He placed particular value on speed. You could add bulk and improve technique, he figured, but your ability to beat an opponent to the spot was crucial, especially in the vertical game.

This obsession with acceleration was so intense and unwavering that friends today suggest it underscored his toxic relationship with Marcus Allen. Yes, the running back held out (and eventually sued the Raiders to become a free agent, in 1991), but that was nothing compared to Allen's mortal sin, in Davis's eyes, of lacking quickness. One Raiders exec back then told the Los Angeles Times, "Al is upset because Marcus can't run fast enough.... Of all the silly damn things. Marcus will be in the Hall of Fame and Al will say, 'Yeah, but he could only run 4.7 [in the 40-yard dash].'"

Davis versus Allen (class of '03) was, famously, less a feud than a war. But it was also an exception. For all of Davis's quirks, this might be the most pronounced: Despite the fact that he was never a player, he was—Allen aside—uncommonly sympathetic toward his foot soldiers. "One of Al's firmest beliefs was standing on the side of players," says Hue Jackson, who coached the Raiders in '11. "In his mind, without them there is no league."

It's likely no coincidence that longtime NFLPA head Gene Upshaw (class of '87) played his whole career in a Raiders organization that viewed players as the lifeblood of the sport—as people, not dispensable labor. It's no stretch to suggest Davis's most enduring legacy resides in this sensibility, which expresses itself today in everything from health and safety issues to the right to protest.

In Jackson's first month as Raiders coach he suggested organizing a spring alumni gathering. Davis had two conditions: 1) No alcohol. 2) He needed to see the guest list before invitations went out. Jackson understood the first rule—"Who knows what could happen; I'd heard all the stories." As for the second, it eventually surfaced that Davis was slipping payments out of his own pocket to retired Raiders who'd fallen on hard times, and here he wanted to be sure attendees didn't share this information, potentially creating jealousies or shame. "He was a dictator in his way," says Jackson, "but he always dictated from the good."

Sometimes this entailed crafting creative solutions. "He thinks of things other people don't think of," Mike Madden, a former Raiders exec, once marveled. "He prides himself on that. You know when Dallas drafted Herschel Walker, a star halfback in the USFL, using a low-round pick [in 1985], Al was kicking himself. 'That's never going to happen again—that's something I do.'"

So it was that two years later the Raiders took a seventh-round flyer on a running back from Auburn. Bo Jackson had left football behind and was playing pro baseball, but Davis had a plan: The two seasons didn't overlap much; tell Jackson he could moonlight. "It was an unbelievable move," Madden said. "Don't ask him to [pick a sport]? Who else would have thought of that?"

Mike Madden spoke from professional and personal experience. His father, John, was a 32-year-old linebackers coach when Davis offered him the Raiders' top job, in 1969. No matter that John Madden had never been a head coach at anything above a junior college. Davis deemed him the best man for the position, a notion Madden (class of 2006) supported with seven division titles, one Super Bowl win (XI) and nary a season under .500.

After Madden—who remained fiercely loyal to his old boss, though he did say Al "isn't for everyone"—Davis hired Tom Flores, in 1979, making him just the second Latino head coach in pro football. (Flores would later become the first minority head coach to win a Super Bowl.) Given plenty of opportunity to take a victory lap for this diversity hire, Davis declined. He knew Flores only as a former Raiders QB who, in Davis's estimation, was the most qualified man for the job.

In 1989, Davis made Art Shell the first black NFL coach in the modern era. Again, Raiders employees encouraged the owner to embrace a moment of favorable publicity. He declined. "I got the best guy," he muttered. "End of story."

This open-mindedness—and humility—applied not only to coaches. In 1983, Davis hired Amy Trask as a legal intern tasked chiefly with helping the Raiders win their battle with the NFL over their move to L.A. Over the next three decades Trask rose within the organization, including a stint as CEO. "He was ahead of his time in many, many, many regards," says Trask, now an analyst for CBS. "He hired people—and, yeah, fired and cussed at people—without regard to race, gender, religion, ethnicity or any of these individualities."

As Davis obsessed through the years over the ther-modynamics of winning, he reached a conclusion. Part of victory entailed superior players executing superior plays; the "army of men," as Davis called his teams, had to operate with discipline and precision. But winning also came from differentiating your team. Much as Davis loved the NFL, his motivation also came from ensuring his Raiders stood apart from the rest of the league.

To that end, he devoted great time and energy to what we would now call "building brand loyalty." Though colorblind himself—not only figuratively, but literally—he recognized the symbolic power of image and design, so much so that in 1963 he unilaterally changed the Raiders' colors from black and gold to silver and black, dressing himself in that scheme seven days a week.

So, too, did Davis grasp the power of the slogan. There are entire Madison Avenue creative agencies that have yet to concoct a single catch phrase as potent as any of Davis's three gems. Pride and Poise. Commitment to Excellence. And, of course, Just Win, Baby.

As Davis was coming up, sports owners were largely faceless. (Name the owner of, say, the 1984 Detroit Tigers. What does Joe Robbie look like?) But Davis knew that he, personally, could play a role in the Raiders' singular mystique, and he cultivated a celebrity force field to rival that of his players. He'd stand on the 50-yard line during warmups, glowering at the opposition. While he seldom gave interviews, he made sure TV producers knew where he'd be sitting during games—a leaf of playbook that Jones and Robert Kraft, among others, have lifted.

Another of Davis's organizing principles entailed seeking every conceivable competitive advantage, on the field and off. Sometimes this meant smudging the line between gamesmanship and cheating; sometimes it meant swerving over the median. Teams reliant on the running game complained that when they played in Oakland, the grass was soggy from overwatering. They reported seeing strange men in the bleachers when they practiced.

Some of the accusations were real. Lester Hayes did put Stickum on his hands to aid in intercepting. Davis himself did use the occasion of Valley's attending the 1972 Summer Olympics, in Munich, to get a leg up: He drafted a revised partnership agreement, making himself the franchise's managing partner and de facto general manager, with virtually unchecked powers.

Some of the charges were imagined. Harland Svare, the Chargers' coach in the early '70s, was so convinced the Raiders were spying on him that he would yell into the lights of Oakland Coliseum's visiting locker room, "Al Davis, I know you're up there!" Davis later responded, "The thing wasn't in the light fixture, I'll tell you that." But it didn't matter. For Davis, every moment an opposing team spent worrying about hidden surveillance cameras—or bugs in the locker room or underinflated footballs—was a moment diverted from preparation. Belichick, an unapologetic admirer of Davis's, elevated this art, such as it is.

Davis sought competitive advantages outside the scope of the game, too. In 1980, figuring his team was better off in Southern California than the East Bay, he attempted to move the Raiders to L.A. NFL owners voted unanimously against the move, but Davis armed himself with an injunction. Afterward, the football lifer wedded to attacking offense filed an antitrust suit.

That Davis ultimately won in court only emboldened him. When an upstart rival league, the USFL, filed its own antitrust suit against the NFL in 1986, it was Davis, alone among the owners, who sided with the USFL in agreeing: The NFL did operate in anticompetitive ways.

Davis's Raiders eventually moved back to Oakland, threatened a move to Sacramento, then to Silicon Valley. Altogether, there are too many motions and threats and lawsuits to catalog here, but they distill to this: Like an activist for states' rights fighting a large, centralized government, Davis believed individual teams should hold more autonomy and power than the league itself. This debate over whether the NFL is a single entity or a collection of 32 teams would persist for decades, undergirding everything from free agency to licensing deals.

One legacy of Davis's litigiousness: In 1997 the NFL passed a rule mandating that if a franchise sued the league and lost, it had to pay the league's legal fees. "That was deliberately to make sure Al would feel the pain if he sued again," says Hawkins. Another move aimed rather obviously at Davis: After his various innovations (schemes?) to protect Raiders revenue from NFL money pools, the league added a provision: If a team refuses to pay assessments, the commissioner can in return with-hold TV-revenue distributions. "He was a maverick," says Hawkins. "And yet he contributed in a backhanded way—by being such a total pain in the ass—to a lot of the centralization of the league's power."

And this is a critical point. Davis's influence was often for good. But sometimes it was for ill. Sometimes his impact came, unintendedly, in the attempts of others to stop him. Or to emulate his ways.

The impatience of owners—and, in turn, fans—who think they know better than the coach? Before it became voguish among owners, Davis was putting his coaches on a perpetual hot seat. Glenn Dickey, a longtime Raiders beat writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, remembers watching Davis pace the concourse of the Miami airport in 1970. Oakland, coming off a 12-1-1 season under Madden, had just lost a Week 3 game to the Dolphins, and here Davis wondered aloud whether he should fire the coach, who was in his second season.

Likewise, when Jones takes a hands-on approach to Cowboys football matters, he has a precedent. Davis, often seated in the press box on the road, would scribble plays and formations on small pieces of paper during games. When sequences weren't executed, he'd pound a first on the table. More than once, reporters overheard a Davis acolyte call down to the sideline on behalf of the boss: "Mr. Davis wants a new quarterback now."

Calling Davis a micromanager would be an act of definitional courtesy. Never mind his insistence on being the one to hire assistant coaches, a duty usually conferred on the head coach. He also approved the wording on brochures sent to season-ticket holders. He once told defensive tackle Tom Keating that he controlled the organization down to the wastebaskets.

Hue Jackson recalls that when he interviewed with Davis for the top job, Davis spent most of their three hours diagramming plays on a whiteboard. "I'd never had that kind of interaction with an owner," says Jackson, "where you're not talking about marketing or staffing, but zone schemes and counter-schemes." When Jackson got the job, Davis, then 81, informed him, "You run the team. And you run the offense. But I run the defense."

Bob Mansbach, a longtime NFL producer for CBS, recalls once visiting Davis's Marina del Rey apartment and finding "Al sitting alone in this small place. He's watching game tape and scribbling down plays on a pad that he's going to give to Tom Flores."

Davis had few close friends, at least outside of football. "I'm not really part of society," he once said. Despite his wealth and his fascination for World War II, he traveled to Europe for the first time only when the Raiders played a London exhibition game in 1990. He was 61.

In so many ways Davis prefigured today's workaholic NFL exec. He lived alone through the Raiders' L.A. years, encouraging his wife, Carole, to remain in the East Bay. When his assistants took dinner breaks, he would lift weights and run, reading NFL newspaper clips on the treadmill. When he ate, late at night, often alone, he had a phone brought to his table so he could take work calls.

Even in the years before his 2011 death, at 82, Davis was still attending owners' meetings, still asking indeli-cate questions, still pushing boundaries. Matt Millen was in attendance for some of those sessions, representing the Lions, for whom he was GM. And Millen noticed that when Davis raised his hand to speak, other owners would snicker and giggle. "It used to piss me off," Millen says. "Here's a guy who was the NFL. He didn't just see the changes, he made the changes. He had a tie to everyone from George Halas to Vince Lombardi to John Madden to Joe Gibbs to Bill Belichick. They thought he'd lost his fastball? He was still two levels ahead."

On the subject of two levels: Go up to the second floor of the Raiders' corporate facility in Alameda, head to the back and there sits Davis's old office, untouched, out of some combination of tribute and superstition. Davis's personal effects still dot his desk, his art still lines the walls, his books—mostly covering football and the Brooklyn Dodgers—still occupy the shelves. Occasionally Mark Davis, Al and Carole's son as well as the Raiders' current owner, will duck in to take a call. But otherwise the office is akin to a museum exhibit, the workplace of a transformative figure, that must be preserved.

Such is the life cycle of a pioneer, as well as the nature of competition and capitalism: Others build on ideas and refine concepts, catching up and often turning the innovator into a laggard. You could make the case that Al Davis became a victim of his own visionary success.

His vertical game? Innumerable pass-happy coaches have taken elements and evolved it. Davis's states' rights philosophy would undergird the Cowboys' commercial wars with the NFL and the Patriots' us-against-the-league ethos. Since the Raiders moved to L.A., a half-dozen other teams have moved markets, and virtually every franchise has threatened relocation. (To paraphrase Svare: "Al Davis, I know you're in there!")

Davis knew he was onto something when he recognized the importance of talent assessment, of gauging when a player would hit or pass his prime. This turned into analytics departments, and eventually the Raiders lost this competitive advantage.

Team slogans would be outsourced to marketing departments. Color schemes wouldn't be approved until they fared well with focus groups. Silver-and-black is a good start—but what if we added a splash of teal?

Beyond that, the very idea of Davis would become obsolete. The NFL would become a league of specialization. A football Zelig whose NFL CV included entries for scout, position coach, head coach, GM and owner would be as absurd today as a two-way player who also kicked field goals.

What would Davis make of the NFL in 2019? Would he be pleased that franchise valuations start around $2 billion, a vivid illustration of football's growth as a business? Or would he be resentful that teams are available for purchase only to titans of finance?

Would the tough guy prone to military analogies—the man who famously said, "The quarterback must go down, and he must go down hard"—cringe at the rules protecting passers as a profaning of his sacred game? Or would the godfather of the aerial assault be pleased by the effort to safeguard the men throwing those bombs?

"He would probably see it as soft," says Jackson, chuckling, "that it's more about money than the love of the game."

Would he be pleased that today's Raiders, revisiting the trail Davis first blazed in the 1980s, are relocating after finding a more hospitable and profitable market in Vegas? Or would he fear that the East Bay and the fan base cultivated in his image would be left bereft? Would he accept the attention that comes with Hard Knocks as another of his brand extensions? Or would he resent the media gadflies invading his foxholes and war rooms?

For her part, Trask has given much thought to how her old boss would have reacted to the recent anthem protests, given that they would have pitted his deep sense of individualism against his deep sense of patriotism. "It would have been a fascinating conversation," she says. "He would have talked about the right to peaceful protest, and how quintessentially important it is to this country. And yet he would have discussed his great love for the country and the people who served it. Not everything is binary, and Al knew that."

One would hope, though, that Davis would scan the NFL landscape and realize: He had not just won, baby. He had conquered. He had laid the groundwork for so much, and now others could build on his ideas. This would mark a rare time Al Davis would be happy to have others take the ball and run with it.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.