The Raiders Are Jon Gruden’s Show Now

The Raiders arrived in downtown Philadelphia on a brisk day in December 2017. It was exactly one year after their emerging quarterback, Derek Carr, had broken his right fibula, effectively shelving their Super Bowl aspirations. And now, for the second straight year, the direction of the franchise would change dramatically on Christmas Eve.

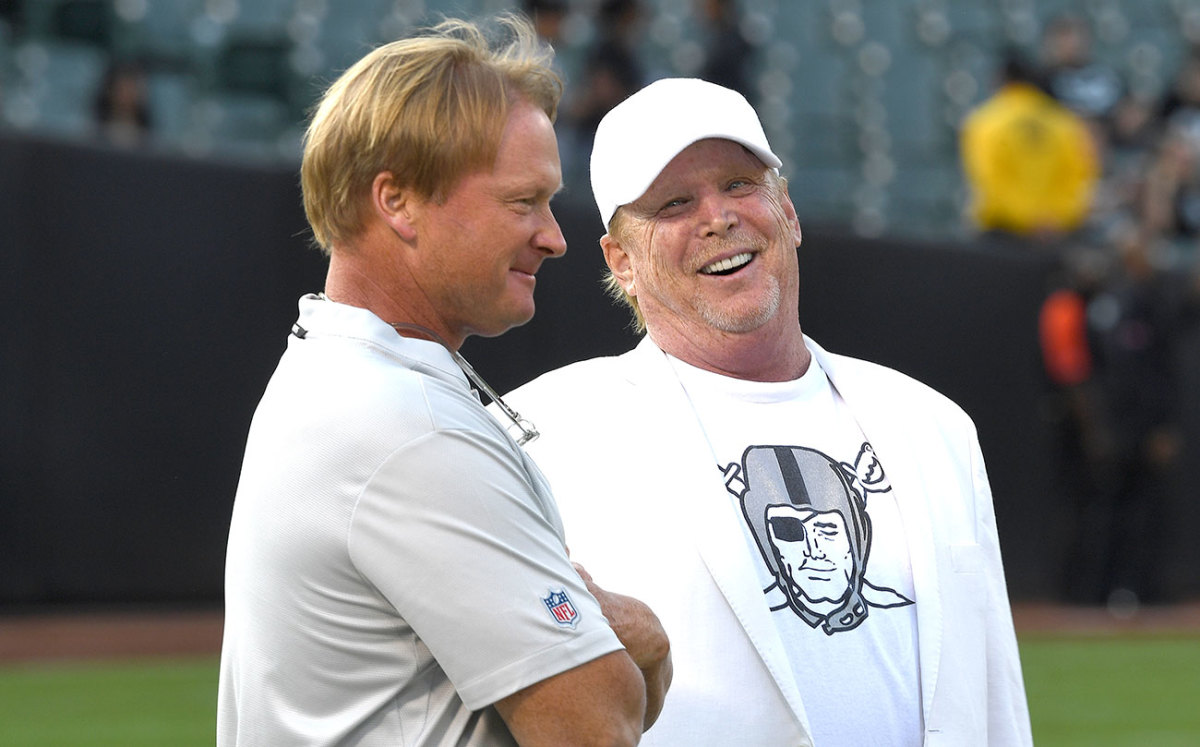

That morning the NFL Network reported that Jon Gruden, in his ninth year as a color analyst for Monday Night Football, had reached out to former assistants, gearing up for a possible return to coaching. The league’s rumor mill had Gruden going to Tampa Bay, where he won a Super Bowl in the 2002 season. But in Philadelphia, where he was in town to call Eagles-Raiders in Week 16, eyebrows shot up when he and his wife, Cindy, entered the Raiders’ hotel near Rittenhouse Square and dined in team owner Mark Davis’s suite late into the night.

The truth was that Davis’s fixation with Gruden, who’d coached the Raiders from 1998 to 2001 under Mark’s father, Al, ran deeper than most realized. In Gruden, Mark saw the only person he believed loved the game as deeply as his father had. Three months after Al died, Mark tried to bring Gruden back to the Raiders for the first time—and he continued to do so for the next six years. When Davis hired Jack Del Rio in 2015, after making yet another run at Gruden, he openly told his new head coach that he would continue trying to land the one who got away. “He was always very straightforward with the fact that he was in love with Jon, and if he had the chance, he was going to hire him,” Del Rio says now. “He said it every chance he got.”

After Del Rio led the Raiders to their best record (12-4) since 2000, Davis rewarded him a new four-year contract, despite reiterating the warning: He would still pursue Gruden. A year later, Gruden wanted back in. Davis gifted Gruden the largest contract for a coach in NFL history—$100 million over 10 years—and, with the team’s move to Las Vegas looming, granted his white whale absolute control.

If the Raiders became the league’s most interesting team the day they hired Gruden, the last 20 months have shaped the true beginning of his second tenure with the Silver and Black, who kick off Monday night against the visiting Broncos. Gone are most of the personnel staffers Gruden inherited, the franchise pass rusher who cost more than he wanted and the Pro Bowl receiver who, Gruden told friends, wouldn’t talk to him. In their place stand Gruden’s handpicked general manager, an overhauled roster, three first-round draft picks expected to start in their rookie season and a mercurial star wideout who had to be restrained by teammates during an altercation with the GM on the eve of the season, after posting a letter from the team detailing his nearly $54,000 in fines.

These Raiders have been remade in Gruden’s image, by the coach and his confidants, who stocked their roster with players they believe “love football,” draft picks who collected wins for storied college programs and renegade talents who, like many before them, came to the East Bay for what could be their last chance. So headstrong is Gruden in his vision for the team that he spent the first 20 minutes of a dinner with a top draft prospect defending the trade of Khalil Mack, saying it helped them get players like Antonio Brown—certainly not expecting then that Brown would be the poster child for the circus many see in Oakland. As questions swirl around the team, the central one remains this: Is this a franchise in chaos led by a coach who long ago lost his touch, or will Jon Gruden, when all is said and done, prove Mark Davis right?

The construction began immediately after the Raiders hired Gruden in January 2018. In the upstairs of the team’s Alameda facility, two offices where low-level staffers would break down film were combined into a room that Gruden began to use as his own scouting quarters. Staff members he hired, including Dave Razzano, the former scout tabbed to be Gruden’s director of football research, worked in there to produce the film cut-ups favored by the new head coach. But the room also housed Gruden’s own draft and personnel boards. These were separate—and in some cases vastly different—from the ones then-GM Reggie McKenzie oversaw elsewhere in the building.

That spring, the dueling draft boards resulted in uncommon jumps for some prospects. One example: defensive tackle P.J. Hall, who blocked an eye-opening 14 kicks at Sam Houston State but didn’t otherwise overly impress the Raiders’ personnel evaluators. They graded him as a middle-round choice, but after Gruden and his coordinators met with McKenzie the week of the draft, Hall shot up the board. Oakland picked him in the second round, 57th overall, significantly earlier than projected. That approach to the first draft under the new head coach reinforced what staffers already knew: Everything goes through Gruden.

The question then, same as now, is: Will it work? Hall started six games in his rookie season, collecting 22 tackles, three for a loss, and failing to register a sack. This suggests the Raiders’ traditional board had him more accurately ranked. But it’s early. Two NFL general managers say they’re not convinced this Raiders’ rebuild will succeed, that a surface glance at Oakland’s roster highlights a lack of both experience and depth. Both also agree with the prevailing leaguewide sentiment on Carr, whom they see as an above-average quarterback capable of winning games in the right system and surrounded by enough talent. Oakland brought in help this spring, ignoring the red flags to get Steelers malcontent Brown and also adding fellow wideout Tyrell Williams, mauling tackle Trent Brown and rookie back Josh Jacobs. But none of them can rush the passer. Neither GM believes Oakland will challenge for a playoff spot, agreeing with almost every pundit’s preseason predictions.

The size—and length—of the contract Davis gave Gruden suggests the owner is willing to be patient, to allow for the construction of both a palatial new stadium in the Nevada desert and a completely made-over organization, from the most important job to the least important player. That contract, like the team’s expectations, builds toward Las Vegas. The first three years of Gruden’s backloaded deal pay $5 million a season, SI has learned, before spiking above $10 million in 2021, the team’s second year in Vegas. Davis will want a return on his investment by that point, but as one rival GM wrote in a text message, “I don’t see them as anywhere close to contending.”

To that end, the extreme overhaul continues. This quest is personal both for the owner whose father traded away Gruden before that 2002 season, and for the coach who won Super Bowl XXXVII that next January in Tampa with a roster he didn’t fashion. Gruden has reconfigured almost his entire roster in just two offseasons, and the flurry of moves at times divided the organization.

Only 10 members of the Raiders’ 53-man roster—and just six offensive and defensive starters—have been with the team since before Gruden’s return. The only other club with a second-year head coach that has experienced close to that degree of turnover in this time frame is the Giants, who hired a new GM and head coach two years ago. Bruce Irvin, an Oakland defensive end from 2016 through November 2018, describes Gruden as a great coach but one intent on moving out players from the previous regime. “He’s a very prideful guy,” Irvin says, “so I think he just wanted to bring his own scheme, his own method, [his own] deal.” (A Raiders spokesman declined to make Davis, Gruden, Carr or new GM Mike Mayock available for this story, citing a desire to “[make] sure that the team’s focus is on football.” The team did not respond to a list of specific inquiries related to this story.)

That pride underlies Gruden’s smartest-guy-in-the-room approach. That he would trade Khalil Mack and Amari Cooper and find better return with the draft picks those moves yielded. That he can see value where others don’t, whether it be spending a third-round pick on Martavis Bryant, who is now suspended indefinitely by the league for violating its substance-abuse policy, or gambling on players with checkered pasts like Vontaze Burfict and Richie Incognito, both new to the team this year. That Brown, a receiver who fought his way out of one of the league’s most stable organizations, would be a team leader, despite the time he missed with frostbitten feet after a cryotherapy mishap and while threatening retirement in his bid to wear a helmet model banned by the league and players union. “Jon likes to operate and bring a mess together, into a workable force,” says Carmen Policy, the 49ers executive who hired Gruden as an offensive assistant in 1990, his first NFL job, because of his football acumen and work ethic.

The biggest mess, at the moment, is Brown. His turbulent start with the team reached a crescendo this week after he posted Mayock’s letter detailing the fines Brown had accrued for a missed practice and walk-through, resulting in a heated verbal exchange (as first reported by ESPN) in which sources say Brown directed profanity toward Mayock. The three-year, $50 million contract Brown signed with the Raiders, after the team traded third- and fifth-round picks to Pittsburgh, includes language stating that his $30 million in guarantees can be voided for unexcused absences from the team or if he’s suspended for detrimental conduct. That would be a potential out for the Raiders—though an embarrassing one—after weeks of drama surrounding Gruden’s highest-profile acquisition. (Update Saturday, noon ET: After Brown requested his release via a social media post, the Raiders did just that.)

“Pittsburgh fleeced this team twice,” says one person close to the Raiders, referring to the Brown and Bryant trades. Adds a rival team executive, “when they let someone like Mack go, and supersized A.B., Jon told everyone what this team was about.”

While much of the league is saying I told you so, Carr now enters a critical season without the All-Pro receiver who was expected to be his top target. The quarterback’s development—and a return to his magical 2016 form—remains central to the Raiders’ strategy. Coming off his leg injury, Carr had seemed “jumpy” and “skittish” in ’17, according to one starter on that team, and then dealt with a fracture in his back. That’s when Davis, upset with a 3-5 record and an offense that had regressed, paid another visit to the object of his greatest affection while the team was staying in Sarasota, Fla. “I took a drive over to Tampa to talk to Jon about ‘How do we fix Derek?’ ” Davis told Sports Illustrated’s S.L. Price in February 2018, “and I started to get the feeling that he felt he could fix Derek.”

Davis had been turned down by Gruden five times already at that point. But during that visit to the strip mall office of Gruden’s Fired Football Coaches Association, and while eating dinner with him and Cindy, Davis sensed a shift in tone. Seven weeks later: the Christmas Eve confab. On the MNF broadcast that week, play-by-play announcer Sean McDonough brought up Del Rio’s future but concluded a change was unlikely, given his recent extension. Gruden stayed silent, next commenting on a Raiders busted run play. One week later Oakland lost to the Chargers on the road, completing a lackluster 6-10 season.

Minutes after the game ended, in the visitors’ locker room, Davis thanked Del Rio for making the Raiders relevant again—and then fired him in favor of Gruden, the coach who could “fix” Carr.

When one former Raiders player would text his old teammates last season—“What the hell is going on?”—he often received the same response: a shoulder shrug emoji.

Gruden’s first season back unfolded unevenly, marked by on-field losses and off-field departures as the overhaul continued. One agent of a veteran player says his client reported back about having to encourage teammates on the sideline during games, telling them even if they didn’t want to play hard for the Raiders, they should at least try for each other and themselves. Many in the building felt a growing divide between the Before Gruden contingent and the After Gruden group. Early in the season, one member of the organization overheard Gruden telling an assistant coach, “Hey, we need to get our guy up,” referring to a 2018 draft pick who hadn’t dressed yet for a game. “It became this quasi-rivalry,” explains one of the Before Gruden Raiders, “that nobody on our side wanted.”

Nothing reinforced that divide more than the Sept. 1 trade of Mack. The personnel department entered 2018 with a plan that included marshaling resources to sign the former Defensive Player of the Year to a contract befitting his generational talent. McKenzie’s first son is named Kahlil (spelled differently), and his co-workers liked to joke that Mack was still the GM’s favorite person with that name. But as free agency began, and members of the personnel staff learned about player visits only after itineraries were circulated around the office, they started to ascertain a new strategy—and they weren’t sure it included Mack.

Back in 2014, McKenzie had asked Davis to sit in on their combine interview with the University at Buffalo pass rusher. But before the draft, Davis told one member of the organization he’d watched tape of Mack and saw him “get his a-- kicked in coverage.” Davis pushed for the Raiders to instead choose Johnny Manziel, according to multiple people with knowledge of that pre-draft process. Some believed Davis’s assessments of both players came directly from Gruden, who made no secret of his affinity for the Texas A&M gunslinger and regularly discussed personnel moves with Davis. Five years later, when Gruden had to decide whether to make Mack a cornerstone of his team (and after Manziel had proven to be a spectacular bust), “I don’t know if there weren’t still hard feelings about who was right and who was wrong,” says a person close to the organization.

When other teams inquired about Mack last July during his contract holdout, they were told he wasn’t available. But as the season neared, the Raiders had not made a serious offer, according to multiple sources with direct knowledge of the negotiations. When the Rams signed Aaron Donald to a six-year, $135 million extension in late August, with $87 million in guarantees, the staggering figure all but cemented Mack’s departure. The Raiders struck a deal with the Bears, who awarded Mack the six-year, $141 million contract, including $90 million in guarantees, that Oakland refused to pay. (Mack declined an interview request through a Bears spokesperson, who wrote in an e-mail that Mack “has moved on from that era” and is focused on pursuing a championship with Chicago).

One member of the Oakland organization lamented to another, “Well, you can’t have three $100 million players”—meaning Carr, Mack and Gruden. He knew the Raiders’ move to Vegas centered on money; specifically, their lack of it. The Raiders, with limited stadium suites and no naming-rights income, ranked last in the NFL in revenue in 2017, at $335 million, less than half of the league-leading Cowboys. In addition to the team’s cash crunch, other executives around the league wondered if there might have been sticker shock for a coach who last navigated the salary cap a decade ago.

Plus, Gruden wasn’t shy about noting that Oakland hadn’t won anything with Mack on the roster—a statement that threatened to alienate the locker room after dividing the front office. As one former Raider puts it, “if Mack sneezed, you’d have 52 players saying bless you.” His previous head coach was so confident Mack would go down as a Raiders legend that, before a 2016 road game in Baltimore, Del Rio snapped a photo of the Ray Lewis statue in front of the Ravens’ stadium and showed it to Mack. “Someday,” Del Rio told him, “you can be like this.” Now, in a team meeting after the trade, Gruden was telling his players that he’d tried to reach out to Mack but Mack didn’t call back, presenting the decision as “out of his control,” according to one player—which countered the widespread sentiment that Gruden, in fact, controlled all.

“Everybody in the building knew he was the best guy, best player in the building,” Irvin says. “When you trade him on the eve of the season, that’s a shocker and a blow to everybody. You see he went to the Bears, and they turned into a damn near Super Bowl team. He changed the whole culture over there; that’s what a guy like that does.”

The overhaul wasn’t close to finished; instead, Gruden doubled down. Seven weeks after the Mack saga, coaches pulled receiver Amari Cooper, a first-round pick in 2015, off the practice field. Cooper’s production had been inconsistent, and when retired Raiders wideout Tim Brown asked Gruden about their relationship, his former coach and close friend told him, “I don’t know. He won’t talk to me.” (Other Raiders say Cooper was quiet but not defiant.) Gruden had said Cooper wouldn’t be moved, but when Cowboys VP Stephen Jones offered a first-round pick before the trade deadline, the Raiders jumped at the offer. It was hard to argue with the move—the Raiders got excellent return on a player they didn’t plan to sign long-term—but seeing Cooper flourish in Dallas (his per-game production last season nearly doubled with the Cowboys) only exacerbated the hard feelings at team headquarters. (A Cowboys spokesperson declined an interview request for Cooper).

“[Mack] was the first blow,” Irvin says. “Then Coop was gone, then it was just all downhill from there.” After a brutal 34-3 loss to the 49ers in Week 9 when Irvin, a team captain, played just nine defensive snaps, he asked to meet with Gruden “before it got to me being rebellious.” He says they agreed to part ways, and the Raiders waived him on Nov. 3. After signing with the Falcons five days later, Irvin walked onto the practice field in Georgia bellowing for all to hear, “I’m free!”

Irvin wonders if he was “too vocal,” but he says he never told his teammates to do anything different than what Gruden wanted. With and without him, the Raiders patched together a hodgepodge defensive front, which generated a total of 13 sacks last season, or half a sack more than Mack notched by himself in Chicago. “It was like a brand-new team toward the end of the season anyways, so there wasn’t even a lot of guys that were going to be too emotionally attached to [the Mack] decision,” says Frostee Rucker, the veteran defensive lineman who played for Oakland in ’18.

Two of the first-round picks from the Mack and Cooper trades have now been cashed in, for Jacobs and safety Johnathan Abram, completing another churn of the Before Gruden roster. And just 19 players from last year’s opening day are still on the team’s 53. “Only one person knows the motivation behind it all,” says one member of the organization, who is not alone in still trying to make sense of Gruden’s deconstruction. Adds Kelechi Osemele, the starting left guard who was traded to the Jets in March, “I didn’t really see—I still have not seen—what he’s done yet.” In other words: Will the change-everything strategy yield results? And when? The Brown drama has been an inauspicious omen.

Early last December, the Raiders’ personnel staff assembled for a Monday morning meeting. The college scouts were in town, reporting back from months spent scouring their assigned territories for NFL talent. This would also be their first chance to hear an explanation for the Mack and Cooper trades, to learn more of Gruden’s plan. Instead, McKenzie began the meeting as Del Rio had started his press conference after the finale in 2017: by announcing his own firing.

The previous day, on the sideline before a win against Pittsburgh that lifted Oakland to 3-10, McKenzie confronted Davis about rumors that he’d be let go. After the rare victory, Davis told his GM that he did plan to make a change. On Monday, neither he nor Gruden gave an explanation to the rest of the personnel department, most of whom McKenzie had hired, for why the GM had been dismissed. But about 30 minutes apart, the owner and his coach delivered an identical message, per multiple accounts: “You are all Raiders—for now.”

Leading up to the ’18 draft, Gruden and members of his coaching staff had picked the brain of Mayock, who was then NFL Network’s lead draft analyst, about some of the players they were considering—not an unusual practice leaguewide. After the phone call, one assistant coach remarked to another staff member that Mayock should be running their drafts. Gruden and Mayock first met about 20 years earlier, when Gruden was the offensive coordinator for the Eagles and Mayock was beginning his broadcasting career. After a narrow search for McKenzie’s replacement, Mayock flew on the Raiders charter home from the Dec. 30 season finale in Kansas City. He was announced as the new GM the next day.

Mayock began joining Gruden for his pre-dawn film sessions, bonding over the very thing that reminded Davis of his father. While members of Gruden’s camp boast about his total control, Mayock prefers toiling in the background, to the point where he declined to wear a microphone during Hard Knocks filming. People familiar with the relationship between the two say that while the direction of the team will shift according to Gruden’s will, Mayock can serve as a voice of reason (though the Brown situation has tested everyone). “They’re two strong-willed people, so I think that part of it might be hard, but I’m sure if there are times when they don’t agree, they’re talking through it,” says Sean McDonough, who has worked with both men as broadcasters. “They both just want to win.”

Their approach to the Antonio Brown saga has reflected their personalities: Gruden playing the exaggerated good cop; Mayock sternly telling reporters Brown needed to be “all-in,” then issuing him the fine letter that led to Wednesday’s blow-up. Brown decided to play this season with a legal Xenith helmet model only after a second helmet grievance hearing, in which the NFL used a tweet lauding the helmet performance rankings from Brown’s own lawyer as a piece of evidence in deciding against him. After this week, outsiders were already questioning the rookie GM’s handling of his first public crisis.

In January, Mayock told the holdovers from McKenzie’s staff, whose contracts were set to expire after the draft, that they had four months to prove themselves. But Mayock also sent most of the scouting employees home before the draft, leaving them to find out from the TV broadcast that the team had used its top pick on Clemson defensive end Clelin Ferrell, whom both of the rival general managers considered a reach at fourth overall. A friend of Bill Belichick’s from the 1980s, when Mayock was a defensive back for the Giants and Belichick was an assistant coach, the new GM knows the value of secrecy. But the move also closed the final chapter of the past era. Some scouts were brought back after the draft, but five personnel employees left the team in the months following McKenzie’s firing. First the coaching staff, then the roster, and then the personnel department had been rebuilt. The separate scouting quarters near Gruden’s office have since been dismantled.

Three weeks before this year’s draft, Gruden and a Raiders contingent arrived in Dallas for a meeting that wasn’t so secret. The group included Mayock, offensive coordinator Greg Olson and franchise legend Tim Brown. They were there to work out an intriguing young quarterback prospect: Kyler Murray.

Over dinner at an upscale steakhouse, at a location leaked to former Cowboys executive Gil Brandt, Gruden told Murray he had a surprise in store for him. The next day the coach fell into typical form at Murray’s workout at Highland Park High, with Gruden yelling and sweating as he raced around the turf like a blitzing linebacker. Murray threw more than 50 passes that day, by Brown’s recollection, and just one of them fell incomplete. Afterward Gruden and company pulled out Oakland A’s baseball caps—the team that had drafted Murray with the ninth pick in 2018, before he chose football—and implored him to take a picture with them. The quiet superstar reluctantly obliged, wading into the circus, even signing the hats.

Then things got weird: The Raiders’ official Twitter account posted a photo of Murray with Brown, a friend of the Murray family. The caption read, “Just Heisman stuff.” Carr noticed, and he responded via Instagram with a post effectively saying, I see you. “Look,” Brown says, “I’m down there with the head coach and the GM. [Carr] shouldn’t be worried about me in the picture. He should be worried that they’re down there.”

Carr remains the centerpiece of Gruden’s plan, the star around whom the coach has chosen to rebuild—for now. The quarterback, who signed a five-year, $125 million deal in June 2017, “fully” bought into Gruden immediately, former teammate Rucker says, “and that’s why he’s still there.” He went so far as to buy a house in Vegas next door to his head coach. But like Gruden, Carr must show his value soon; the team could move on from him after the season at the marginal price of a $5 million dead cap hit.

Highly publicized tension bubbled over between the two at times last year, including one sideline spat caught by TV cameras after an incompletion. Spotting Gruden’s red face, former Raiders tight end Lee Smith pulled Gruden back. But running back Jalen Richard, for whom that pass was intended, asserts that the tension might bring out the best in his QB, describing a “click” he sees in Carr when his head coach challenges him. “You can tell it gets under DC’s skin a little bit when the coach is yelling at him,” Richard says. “He needs that, and it helps him. It helps him so much.” Rich Gannon, who played three of his best seasons under Gruden from 1999 to 2001, says he jokes with the QB that Gruden is easier on Carr than he ever was on him. Gannon recalls Gruden screaming at him while he was standing over center, and Gannon turning around and screaming back, but he says it elevated his play. He was named league MVP in 2002.

Tim Brown, who speaks regularly with Gruden, believes his former coach can help Carr return to his pre-injury form, if the quarterback follows the rules of Gruden’s system, freelancing less. Gruden’s philosophy remains grounded in West Coast principles, the short-efficient passing game that bolstered Carr’s career-best 68.9% completion rate last season. The coach had hoped his new receivers and better protection would allow for a stronger vertical game this year; Gruden has always had a knack for designing formations and route combinations to get his best players open, a critical task with or without Antonio Brown. “There’s no doubt in my mind he could be a franchise quarterback,” Tim Brown says. “Let me just say this to you: Did you ever think Rich Gannon would be the MVP of the NFL?”

Hanging over every decision Gruden’s Raiders have made in the last 20 months is the $100 million question: Will it work? There were similar doubts at the beginning of his first tenure with the Raiders, way back in 1998, when the talk radio chatter centered on his youth and inexperience. Now he’s 56, and skeptics wonder if the game has passed him by, if he’s too set in his ways, not as smart as he thinks.

As the curiosity swirls, the Raiders haven’t wanted to let peering eyes in. The team was already ticked off about the schedule assigned to it by the league office, which includes a six-week stretch without a game in Oakland, and commissioner Roger Goodell got an earful when he called in June to tell the Raiders they’d been chosen for HBO’s Hard Knocks. The show’s season finale this week didn’t air Mayock’s conversations with the players who were let go on cutdown weekend, a series mainstay, nor did cameras film in the quarterbacks’ meeting room (which during camp in Napa was one and the same with Gruden’s hotel room). Brown’s dustup with Mayock came one day after the finale.

Beyond Brown, the players on Gruden’s remade roster, coaxed into the daily affirmation of knocking three times if they’re with the coach, assert that they’ll be better than expected this year, that when they get to Vegas they’ll shock the world, that Gruden will lead them where he promised. Others see Gruden as unchanged and unapologetic, still hyper, still headstrong.

On another Christmas Eve, in 2018, Mark Davis watched from underneath a canopy as rain fell on the Raiders the night of the penultimate game of another disappointing season. Oakland would finish a miserable 4-12. But with its coach locked in for nine more years, Davis’ faith in Gruden remained unshaken. Standing with Jay Rothman, ESPN’s longtime Monday Night Football producer and another Gruden confidant, Davis believed the gray skies overheard would soon clear—even if that hasn’t yet been the case. “I would sign him for 20 years if I could,” he said.

This remains the bet the owner made: not on Las Vegas, even, but on Jon Gruden being right, and the larger football world being wrong. There’s no easy answer, not yet, just another season that marks the real beginning of Gruden’s second tenure. “Things are tense,” says one current member of the organization who remained wary to speak for all. “Right or wrong, the results will show on the field.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect subsequent news.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.