The Final Days of Eli (Or Not. With Him, Who Knows?)

Eli Manning’s three daughters stand shoulder to shoulder in the first row of the family’s MetLife Stadium suite and wait for their father. After games, the Giants’ quarterback always walks off the field through the tunnel closest to his brood, glances into the crowd—no matter if the fans are cheering or booing—and waves to his girls, wife Abby included.

“Where’s daddy?” asks six-year-old Lucy, who the family calls Lou, her forearms resting on a glass partition. She wore her dad’s No. 10 Ole Miss jersey today in hopes that it would bring him luck against the visiting Bills, rewinding the inexorable gears of time.

Abby doesn’t know where her husband is. She scans the field. Even seven-month-old Charlie—Chill Man Charlie, they call him, because he never cries—appears to be looking. Daddy is nowhere to be found.

Five minutes pass. The stadium is nearly empty when Abby decides they somehow must have missed Eli come off the field. “That’s a first,” she says. Then she squirts ketchup on a hot dog, wraps it in cellophane and places it in a bag to bring to her husband, along with two Bud Lights.

* * *

This is the last game before Eli Manning will be benched, likely for the final time, likely ending a long, incomparable, inexplicable career. One hundred sixteen wins—more than Bradshaw and Starr and Aikman. Three hundred sixty-two touchdowns—more than Elway and Unitas and Montana. Two hundred forty-one interceptions—more than all but 12 other passers ever; the league leader three times. And those two Super Bowl wins, each with last-second heroics that defied explanation. Nobody in the suite expects this outcome when they leave the stadium. They know the end will arrive at some point, of course. But there is hope that Eli, at 38, has one last trick left, one more improbable escape, one final surprise to reveal right as everyone declares him done.

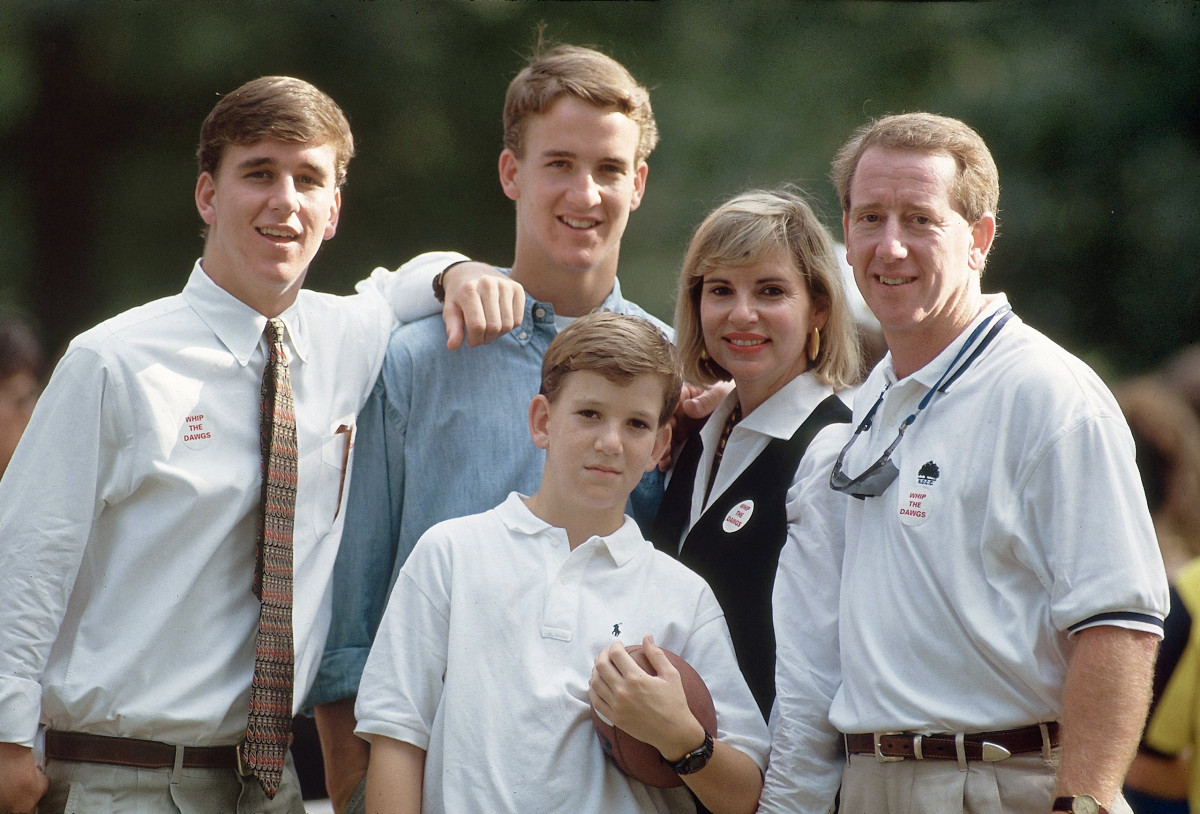

It has always been a struggle to explain Manning. His career, his personality, his existence. The youngest son of America’s first football family never adhered to any norms, never fit any preconceived notion of what a football player should be. He’s been watched and studied his entire life, written about and dissected, and still no one has been able to define him.

He’s always liked it that way, the air of mystery, friends say. He’s found it hilarious, really, that his life has been reduced to a caricature, to memes and the Manning Face. Those closest to him—teammates, friends, family—all aver that the outside world has never understood the real Eli Manning, although in some ways neither have they. As Manning’s career has strained through its denouement, they, too, have often been left guessing at how Eli truly feels.

Nobody knows for certain if this is the end, but if it is, this is what it looks like: A Sunday afternoon in New Jersey, Week 2, unseasonably warm, the air heavy, one of those September days where the calendar appears to have moved on to autumn before the weather is ready to comply. Eli is barely a quarter of the way into the 232nd start of his career—he’ll finish the day with his 116th loss, a symmetry oddly befitting—when the boos come. They start after receiver Bennie Fowler (who will be cut two weeks later) drops a third-down pass that would have been several yards short of the marker anyway, and they resume seemingly every time the quarterback exits the field. Occasionally they come interspersed with tepid cheers, as if fans don’t quite know how to act. Impatience battling nostalgia.

Abby watches most of the game in the outdoor section of the Mannings’ suite, sitting in the last row to avoid the sun and holding a team roster because she doesn’t know many of the players her husband is throwing to. It’s the first time she’s ever had to do this, such is the extent to which injuries and suspensions have already depleted the Giants’ offense. Not that the circumstances have cushioned her husband from criticism. This doesn’t surprise the Manning family; it’s always been this way. Such is the position, the city, the last name. Nobody is looking for pity.

Olivia Manning, Eli’s mother, sits beside her daughter-in-law, doting on the girls as they run around with cups of popcorn and handfuls of Gummy bears. The two women take turns holding Charlie—his blue onesie spotted with miniature footballs, his blue eyes wide—and marvel at the boy’s placid comportment. As the crowd veers between cheers and jeers, Charlie neither laughs nor cries. He simply takes everything in.

Archie Manning, Eli’s father, sits alone inside the suite, mostly in silence, watching intensely. As the clock winds down on a 28-14 loss, Eli heaves the ball downfield hoping for a miracle, like he so often does. The pass is intercepted. This pains Archie, who long ago stopped trying to convince his son to take fewer risks at the end of games that are already out of hand. When Archie was playing, he always worried that one more pick would land him on the bench. But he learned early in his youngest son’s career that Eli has never cared about stats, or optics, or potentialities. That’s just Eli. It’s a phrase used often by those who know him best, a catchall for any behavior that typifies the man they long ago gave up trying to explain.

After the turnover, a chant breaks out directly in front of the suite. The fans, several with Manning’s name stitched across their backs, are openly clamoring for Eli’s successor. “We want Dan-iel! We want Dan-iel!”

One of Manning’s daughters asks what they’re saying.

“Nothing,” Abby responds.

* * *

Three days later, Eli Manning settles in front of his locker at the Giants’ practice facility. He’s wearing a gray team-issued T-shirt and red-and-blue shorts. His face is dotted with stubble. Twenty-four hours earlier the Giants announced they were benching their quarterback of the past 16 seasons and replacing him with rookie Daniel Jones. It was a move surprising only for its timing, after just two games.

An expanding mass of bodies circles Manning. Reporters hold out microphones and cameramen strain to lift bulky camcorders over their heads to view past the phalanx, focusing on the quarterback’s face, which remains unmoved. Eli talks for several minutes, answering every question. He’s disappointed, of course, but he’ll handle it. He gave it a shot, worked hard, did everything he thought he could. But now he’ll support the rookie, provide him with decades of accumulated advice. At one point he’s asked if this is the end of Eli Manning.

“I’m not dying,” he says.

Shaun O’Hara, Manning’s center for seven seasons, until he retired in 2010, is frustrated. He needs to say the things he knows his quarterback never would: that the 94-year-old franchise is in complete disarray, that management has done an awful job the last decade of drafting players around their quarterback, that the line they’ve often put in front of him is “downright criminal,” that they’ve “wasted [Eli’s] prime years.” O’Hara bemoans the timing of Jones’s promotion. The team, he says, is using Manning as a scapegoat to cover larger issues. “Even with all the dysfunction around him, Eli hasn’t said a peep.”

That’s just Eli. Teammates say that in a league where players care most about shaping their narrative, Manning has never attempted to dictate how others view him. As a result, he’s woefully misunderstood. Outsiders will plug in their own constructs to describe the quarterback—goofy, simple, boring, like adjectives into a Mad Libs template—only, they tend to get it wrong. These teammates laugh when they encounter fans who question Eli’s toughness, or how much he cares. They cite the extra meetings he’d run every week, on his own, for running backs and receivers; the exhaustive tape cut-ups he’d create for other players to study. “He worked his ass off,” says former Giants tight end Kevin Boss.

There’s an argument to be made, teammates say, that Eli is the last truly masculine player in the league, the old stoic cowboy archetype. When he was hurt, he’d go into the training room at 5 a.m., before any other player arrived, because he didn’t want anyone to see him that way. He once went on a week-long offseason vacation with O’Hara to Napa Valley, and the two spent nearly every minute together. One day after returning, O’Hara was shocked to see reports the quarterback was having ankle surgery. Manning had never mentioned it.

Even those in Eli’s innermost circle rarely get the sense that the outcome of a game or the constant criticism—really, anything at all—has ever affected him. Tim Hasselbeck spent countless hours alone with Manning as his backup in 2005 and ’06, and only once did he encounter anything remotely revealing. Days after a loss to the Bears, the two passers were sitting in the Giants’ darkened quarterbacks room, watching film, when suddenly the tape cut out. Hasselbeck figured the projector had froze, but when he turned around he saw Manning staring at him through the darkness. “All these people are saying I’m a bust,” Eli said.

It was a fleeting moment, the only time Hasselbeck ever heard Manning acknowledge the outside noise. But “part of me,” Hasselbeck says, “was like, Dang, dude—you are human.”

Other teammates say that, privately, Manning had ways of addressing his unparalleled stresses. They’d sometimes see him meeting on off days with a sports psychologist. One teammate says he accidentally walked in on such a session at the team facility and saw handwritten on the whiteboard: 1) PLAYING IN NEW YORK 2) ARCHIE’S SON 3) PEYTON’S BROTHER. Eli and the psychologist, this player recalls, were discussing how anyone could possibly navigate those circumstances—pressures, other teammates say, that only someone with Manning’s particular sangfroid could handle. Occasionally, coaches would try to glean information from the psychologist, like what Eli really felt about a particular game plan. Anything to get a “little peek behind the curtain,” one former coach says.

The world got its own peek when Manning appeared to choke up, ever so slightly, talking to the media after Ben McAdoo shockingly benched him two years ago, ending a streak of 210 consecutive starts. Behind the scenes, Manning told O’Hara it wasn’t the streak ending that hurt him—he’s never cared about records—but rather what it represented: That I am not going to be there to lead my teammates. That, O’Hara says, “was the toughest thing for him.”

When Giants brass fired McAdoo and general manager Jerry Reese a week later (seemingly a result of the benching fallout), teammates say the quarterback took no pleasure in reclaiming his starting role, harbored no feelings of vindication. He hated to feel like he was the cause of anyone losing a job. His message to the team was simple: Let’s go back to work.

That offseason, Manning’s wife and some former teammates took him out for a birthday dinner at Del Posto, an Italian eatery in Manhattan, where they ate steaks, drank red wine and reminisced about past Super Bowl runs. Rumors were swirling around that time that Manning might welcome a trade to Jacksonville, where he’d hypothetically reunite with his former coach, Tom Coughlin, so friends bought the birthday boy a Jaguars T-shirt as a gag gift. Manning received the gesture with only an “F you smirk,” says Chris Snee, another former teammate left to search the unspoken void for meaning.

O’Hara did broach the topic of retirement this past offseason, after yet another difficult year, asking Manning if he still wanted to play. The answer was definitive: Absolutely. Not because he wanted to prove anyone wrong or etch his name in the record books; no teammate recalls ever hearing Eli discuss his legacy or place in history. He wanted to continue playing simply because he still enjoyed it and thought he could compete at a high level.

The Giants must have had the end in mind, though, when they drafted Jones, out of Duke, with the sixth pick in April. Manning immediately called his eventual successor and reached him at the airport in Nashville. “Welcome,” Eli said. “I’m excited to be teammates.” Indeed, when Jones arrived at training camp, Manning was happy to assist with film study, taking the 21-year-old to play golf and out to dinner. He also razzed Jones like he would any newcomer, making him sing during team meetings. When the rookie’s rendition of “Wagon Wheel” was poorly received, Manning made him try again, this time assigning him T-Pain’s “Buy You a Drank.”

That’s the Manning teammates say is universally loved. What the quarterback has always enjoyed most about his sport is being part of a team, the camaraderie and cold beers on bus rides home. That Eli was still there one day after his latest benching. Right before the media swarmed the quarterback’s locker, he and tight end Evan Engram, a fellow Mississippi alum, were joking about the upcoming Ole Miss game. “Same exact Eli,” Engram says. “Always having fun.”

Snee wasn’t angry about this benching—not the way he was two years ago, when he and several other former Giants planned to wear Manning’s jersey to the next home game in protest. Nor was he shocked. Only sad. He knew how excited Eli had been about this season, how much he loves being a Giant. He understood how it pained the quarterback, not being able to help his teammates. So he texted Manning and asked how he was feeling.

“Disappointed,” Manning responded. “But I’ll be O.K.”

“I know you will,” Snee typed back. “You’re the toughest scrawny guy I know.”

* * *

Justin Wade did not text Manning after the benching. Eli’s freshman-year roommate at Ole Miss understands his friend doesn’t need the encouragement, doesn’t want it. “He has an iron stomach,” Wade says. “He eats it.”

Wade had spoken to Manning less than a week before the demotion, but they didn’t talk football, of course. There’s an unofficial rule for all of Manning’s friends: Never discuss the sport. Instead they spoke about their children. Wade, too, has daughters, and they often empathize with one another over households bubbling with emotions. That’s about as deep as they get.

James Montgomery understands. He’s one of Manning’s oldest friends and, a few days after the benching, he hadn’t spoken with Eli yet either. He’s gone back and forth on what he could really say, knowing Manning has no desire to talk about it all. He understands the role Manning likes his friends to play: make him laugh, reminisce, take him back to “the simplicity in life.”

Over the years, when friends have come to visit for home games, it’s been tradition for Eli to drive everyone afterward to his Summit, N.J., home in his grey Toyota Sequoia, win or lose. Manning puts on music—he’s known to have a playlist for every occasion—and start a dance party for his daughters, before stepping out to bathe them and put them to bed. There’s food—sometimes Abby gets steak and pasta catered, other times they just order a pizza—and wine, which Manning picks out from the well-stocked cellar in his basement. Over dinner he will ask everyone about their jobs, their families, their children. Football will never be discussed.

Eli’s brother Peyton is the embodiment of the cliché player who hates to lose more than he loves to win. But that’s never been Eli. Friends say he’s always had a healthy perspective about his job. After the Giants lost 23-0 to the Panthers in January 2006, Manning’s first postseason game, the quarterback still went out with friends for a celebratory dinner in Manhattan. He understood he’d worked as hard as he could, did everything in his power to win, so there was no point in agonizing. There were more important things in life, and he’s never wanted football to define him. Eli has “remained remarkably similar, in the best of ways,” says Brandon Berger, a friend since first grade. “The same priorities; very rooted in his family and friends.”

When Eli was drafted with the first pick in 2004, friends all believed his personality would eventually shine. His droll sense of humor. His tendency to quote Fletch or Caddyshack or the old Deep Thoughts by Jack Handey skits from Saturday Night Live, which a younger Manning was known to recite to confused fans who approached him at bars. And, of course, his passion for karaoke. At Ole Miss, Manning’s karaoke machine had been his most prized possession. Nights out often ended back at his apartment, with the quarterback in jean shorts and a tank top screeching out Elton John, Def Leppard and Johnny Cash to a packed room. He was rarely on pitch, and he often looked quite goofy, but Eli has never cared what people think of him. Friends say no one is more comfortable in their own skin.

Which is why the public never saw that side of him, friends now realize. Eli has never wanted to be known or understood. He’s never worried about how he’s viewed. When people tell him to start a Twitter account, he truly doesn’t understand why anyone would care what he has to say. Even as the star quarterback in the league’s biggest media market, friends say he has clung to being a normal guy with a normal life. Privacy has always been a chief concern, and he often laments to those close to him that the camera phone is the worst invention the world has ever seen. Forced to accept that reality, he still has fun with it. If Manning encounters a particularly obnoxious fan who harasses him for a picture, he’ll hand the phone to a friend and whisper instructions: Just get half of my face.

For as much as he conceals, though, some of the common notions about Eli are relatively accurate. Like the fact that he doesn’t get overly emotional, whether it be over a touchdown or an interception or worse. Friends say they’ve never seen him rattled, never seen him lose his cool, never seen him overcome with anger or excitement. He just isn’t affected that way. Years ago, on a flight home from London with friends, a loud explosion shortly before takeoff caused panic and forced everyone to deplane. In the terminal afterward, friends realized they didn’t know where Eli was, so they notified a flight attendant. Manning was soon found, fast asleep in his seat.

Even in recent years, as the O-line turned porous and the media bashed the Giants’ front office and the team missed postseason after postseason, Manning has never joined in when acquaintances have complained about the circumstances. We’re dealing with it, he’ll say. Or: These guys are doing their best. If there’s been an existential crisis brewing underneath his placid exterior, even his best friends don’t know about it.

Days after the Giants drafted Jones, signaling the beginning of the end, Eli was a groomsman in a friend’s wedding. And if anything bothered him during that weekend in Savannah, Ga., nobody could tell. Manning led an uproarious roast of the groom, sang and danced, and even posed for pics with two high schoolers who’d crashed the event. He also short-sheeted the newlyweds’ bed on their wedding night, calling the groom at 8 a.m. the next morning to ask, “Did you get a good night’s sleep?” as he giggled hysterically.

That’s the Eli friends adore: an oversized man-child who just wants to keep things light and fun. His baseline mood is happy. “I feel terrible for him, but I don’t feel sorry for him,” says Wade of the latest benching. “It’s almost like he was raised for this.”

* * *

Archie and Olivia Manning used to worry about their youngest child. They were confounded by him. Archie would tell friends he was scared that he’d never understand what was going on beneath the surface. And in many ways, he never has.

They’ve since come to realize, though, that Eli is just Eli. There’s no other way to explain it. He has his own way of handling things. Archie thinks Eli simply understands life better than most.

When Olivia was pregnant with the third of her three sons, she and Archie, in his 10th year as the Saints’ quarterback, looked at the NFL calendar and noted: If New Orleans made the playoffs, there was a good chance Archie would miss the child’s birth. It would’ve marked Archie’s first trip to the postseason, but husband and wife always had such blind hope. Instead, the Saints went 1-15, and midway through the season Olivia used the pregnancy as an excuse to stop attending games. She couldn’t handle the fans booing her husband any longer.

From birth, Eli was different—nine pounds, 14 ounces; both of his brothers, Peyton and Cooper, weighed over 12 pounds. Eli didn’t speak until he was three, not because he couldn’t but because he didn’t want to. Instead he’d point and gesture, and everyone would attempt to figure out what he meant.

Early on, he would never cry, though as he got older his brothers took great pleasure in trying to make him do so, pegging him at short range with tennis balls or holding him down and knocking on his chest. But they never could manufacture tears. Three-year-old Eli once fell down the 18 steps into his family’s foyer—it’s lost to history whether he was tripped or pushed—and his brothers seriously worried that he was dead. Instead, Cooper says, he popped up and wandered to the kitchen in search of a turkey sandwich. “The durability of the guy, both psychologically and physically,” says Cooper, “has been nothing short of a miracle.”

Well documented is the degree to which Peyton’s life always revolved around football. Archie once had to tell his middle son to go to the movies, get a girlfriend, have some fun. But he never had that talk with Eli, who as a middle schooler would go off to camp every summer—Peyton went once and deemed it not serious enough—and later, as a high schooler, was often found carousing on Bourbon Street. Archie and Olivia are still finding out about parties Eli threw in their house when they’d go away.

Kind and gentle, Eli always seemed more delicate than his brothers. One middle school basketball coach with a propensity for screaming at players—most of all Peyton and Cooper—told Archie and Olivia that he couldn’t bring himself to yell at their youngest. It would be like yelling at Bambi. And that disposition has often left Mom and Dad wondering, concerned. When Eli was in high school at Isidore Newman, Archie worried whether Eli was ready for the pressures of following in his brothers’ footsteps, whether his arm was strong enough. Then Eli became the only Manning to earn All-State three years in a row. In college, Archie wanted Eli to redshirt his freshman year; he wasn’t sure his son was ready, right up until his first start, two seasons later. When Eli threw five touchdowns in that debut, against Murray State, Archie thought: All right. He’s going to be fine. But even after Eli made it to the NFL, Archie called the Giants’ offensive coordinator, Kevin Gilbride, following a particularly difficult loss early on. Archie never inserted himself into his sons’ careers, but he hadn’t heard from Eli in days. “I just want to know one thing” he told Gilbride. “Just tell me my son is all right.” “He is,” the coach responded. Manning had acted no differently at practice that week. Or any week, for that matter.

In many ways, Peyton was the opposite. At Tennessee he would call Archie daily for advice; Eli never reached out in that way, despite playing at a school where his father was revered. When Peyton’s NFL career neared the end—when he got hurt and then released by the Colts, then got hurt again in Denver and contemplated retirement—he’d often call Archie to sort through his conflicted emotions or visit his parents in New Orleans just to brood. Again, Eli never looked for counsel. Over these past few years, under frequent assail, his future constantly in question, he hasn’t once talked to Archie about any of it. Not about the benching two years ago, not about the possibility of retirement or about his future. Even in June, when father and son were together for several days at the Manning Passing Academy in Thibodaux, La., those topics never came up.

Over the years, the Mannings have come to see Eli’s remarkable reticence not as a deficiency or a cause for concern. It’s been his greatest gift. When Eli first arrived in New York, Archie and Olivia worried that he’d be swallowed up by the blistering media machine. They wished their sons were playing in opposite cities—Eli in Indianapolis, Peyton in the big metropolis. They understand now that they had it backwards. “If Peyton goes to New York,” Cooper says, “he would have killed a reporter by Week 2.”

Cooper talks with his youngest brother frequently. They’re incredibly close. But conversations focus mostly on their children’s volleyball games and swim meets, or recommendations for each other’s Spotify playlists. Sometimes Cooper will ask questions bordering on personal, and he’ll get the sense that he’s “going down the none-of-my-business road,” so he’ll pivot quickly. “That’s just Eli,” Cooper says. “I’m also dying to know what he’s thinking about a lot of times.”

Olivia and Abby, meanwhile, text often, each trying to glean information from the other. They spoke this offseason, after the Giants drafted Jones, about what that meant for Eli. They thought it was the least threatening pick out of the options, believing the Giants would give the rookie time to mature. They tried to figure out what Eli might do next, whether he’d get cut or be traded, or if he would choose to retire. Neither had any answers. They weren’t sure how he felt.

Often, Olivia simply commiserates with her daughter-in-law. She’s been in a similar situation, the wife of a quarterback now being booed in the city where he was once loved. In some ways Olivia was relieved when the Giants benched Eli. Finally, the blame and the media bashing would end.

Archie read about the benching on a push notification on his phone. He waited a day to call, and when he did the conversation was matter-of-fact. This is what happened. This is what was said. Eli didn’t complain, didn’t ask Dad for advice. But Archie knows his son must be hurting, and he couldn’t be prouder about how he’s handled the situation. Eli, like always, will be O.K. Dad doesn’t worry anymore.

* * *

Eli Manning is not one of the six captains at midfield for the coin toss in Tampa Bay, Week 3, despite the fact that he’s worn the C on his chest for the past 13 seasons. Instead he stands on the sideline, earpiece dangling from one ear, radio clipped to his belt, a white Giants hat atop his head. Instead he helps warm up the quarterback who replaced him.

Before New York’s final drive, down six, Manning is seen whispering into Jones’s ear, like he’s been doing throughout the game. With just over a minute remaining, the rookie takes off through a seam down the middle and scores the game-winning touchdown, the kind of heroics that defined Manning’s career.

Amid the chaos of celebration, Eli seeks out the quarterback who took his position and wraps him in a hug. “Great job,” he says.

* * *

Nobody knows what the future holds for Eli—not his teammates, not his friends, not his family. They have only hints they’re left to decipher, amateur cryptologists sifting through clues. In past years, when friends have joked, for example, that they wouldn’t travel to Jacksonville to watch Manning play home games, he would remind them that he has a no-trade clause. It’s always been his plan to retire a New York Giant, whenever that day does come. And he’s told those closest to him that after he leaves the sport, he plans to keep his family in New Jersey. Friends don’t believe Manning feels any resentment towards the Giants for benching him, or that he’ll want to go elsewhere just to prove his doubters wrong. So, maybe this is it: 11 more games, a sort of mini-sendoff tour, and then, the end.

Those friends also know how much time and work Eli put in this offseason. They understand how badly he still wants to play, and how strongly he believes he still can play at a high level. Maybe he’ll take a look around the league in the offseason, friends say, searching for the perfect situation, one final season as a starter. They don’t believe Eli even knows for sure yet what he wants to do.

Then there’s the reality of football. Archie’s body broke down at the end of his career. As did Peyton’s. There wasn’t much of a decision in either case; injuries forced them to retire. Eli still feels healthy, and that complicates matters. He also knows, though, that his dad has had nine surgeries in the past five years and now walks with a cane. Archie wonders whether Eli might believe that getting out in one piece isn’t such a bad idea.

Teammates imagine Eli spending the rest of his days as a backup and say that situation would make them angrier than it would Eli. They can’t think of another player with his resumé who’d willingly mentor the kid who took his job. But doing so would be emblematic of his career, the perfect teammate to the end.

Besides, friends say, they’ve gotten the impression that Manning is actually enjoying parts of his new football existence, in an odd way. He has joked with them about the fact that he’s now running the scout team in practice, how his constant checkdowns at the line frustrate the Giants’ defensive coaches. He’s told them how happy he is to be freed of the obligation of press conferences and other stresses. For the first time in his career, he was able to play golf in the middle of the season.

Short of another Super Bowl win, friends feel this might be, in some perverse way, the perfect ending for Eli. He still gets to be part of a team, still gets to goof off for a few more months, but now without the constant pressure and criticism. Finally he’s able to enjoy the parts of football he’s always loved most, without the burdens he’s always shouldered willingly. It all reminds one friend of something Manning told him back in high school, that his ideal career was to be a 15-year NFL backup.

If this is the end? There might not be another player in NFL history whose Hall of Fame candidacy fans and critics will argue about more fervidly. And, friends say, there might not be another player who will care less about the outcome. But everyone who knows Eli agrees he is perfectly suited to handle retirement. If they had to bet, he’ll disappear entirely into domestic life, not join Peyton in TV ubiquity. They suggest, in fact, we may never see Eli again, not in the public eye. Instead, he’ll be the dad who takes his kids to school every morning and proudly mows his lawn on Sunday afternoons.

* * *

Eli Manning’s three daughters stand anxiously in their doorway, waiting for their father to arrive home on Sunday afternoon of Week 4. An hour earlier their dad jogged off the field to a standing ovation from the MetLife Stadium fans, their spirits lifted by a second straight win under Jones. Again, though, there was no wave to the Mannings’ box. Abby and the girls didn’t attend, skipping the first home game since November 2004.

Afterward, when Manning’s friends meet him in the parking lot, it’s the first time that, with no need to shower or do interviews, he’s been in his car, waiting. They joke about his scraggly beard; they never knew he could grow facial hair. He jokes that he still can’t. Then everyone piles into the Toyota and over the 20-minute drive home Manning asks about their summer vacations and what sports their kids are playing these days.

In the end, more than 20 visitors end up at the Manning house—seven couples, with children in tow. As soon as Eli walks through the front door he kisses each daughter and scoops up baby Charlie, cradling him around the foyer, introducing his kids to friends they’ve never met. He puts a country music playlist on the sound system. Then he grabs a beer and heads into his backyard to play Three Flies Up with his friends’ young sons, a two-time Super Bowl MVP hurling high, looping passes as kids battle to catch the ball. For the friends who grew up around the Manning household—Montgomery and Berger are both visiting tonight—the scene is eerily redolent of Archie in his New Orleans yard, 30 years ago.

A catered dinner is eventually served—ravioli and chicken and salad, buffet style—and friends grab plates, sitting wherever they can find seats. Bottles of wine are opened and continuously poured. Children start to fall asleep and everyone else gathers in the living room.

At one point, of course, Jack Handey is mentioned, and Manning’s eyes light up. He lifts himself off the couch and dashes to his study. When he returns he’s holding two books of Deep Thoughts, and as friends gather around he flips through the pages, reading his favorite quotes aloud. Sunday Night Football plays silently in the background, behind the sounds of old friends reminiscing and laughter that fills the household late into the night.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.