Reflecting on Brett Favre's First Victory with the Green Bay Packers

Ron Wolf had been a fan of Brett Favre’s since the fall of 1990, when he had first seen film of Favre playing quarterback at Southern Mississippi. Wolf was then the personnel director of the Jets, and he was bitterly disappointed after New York had missed the chance to take Favre in the second round of the 1991 NFL draft. But later that same year, after Packers president Bob Harlan had hired him as Green Bay’s new general manager, Wolf resolved to make a trade for Favre, who was buried deep on the Falcons’ depth chart. On February 11, 1992, Wolf traded a first-round pick (the Packers had two that year) in the upcoming draft to Atlanta to get his man. The reaction of the Packers’ fans was not optimistic—three winning seasons in the previous 24 years had a lot to do with that. Loyalists who had watched helplessly for years as Green Bay bungled its draft choices and got taken to the cleaners on the trade market were not happy with the decision to surrender a first-round pick for a complete unknown. “Some of the worst mail I ever got was when Ron made the trade for Favre,” says Harlan. “It took guts for Ron to make that move.” No one knew at the time if Wolf’s gamble would pay off. But it wouldn’t take long to find out.

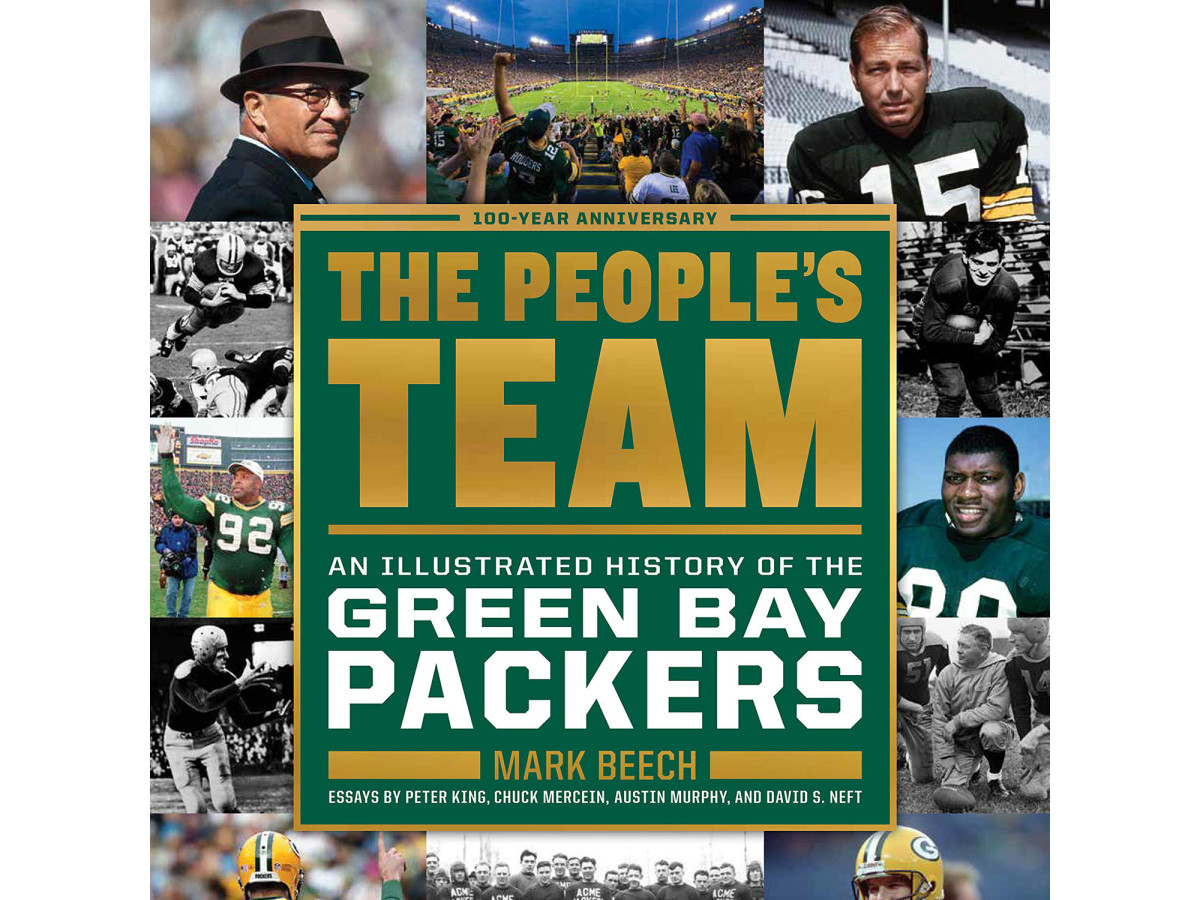

The following is excerpted from THE PEOPLE’S TEAM: An Illustrated History of the Green Bay Packers by Mark Beech. Copyright © 2019 by Mark Beech. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

The Cincinnati Bengals are not traditional rivals of the Green Bay Packers. Green Bay’s history stretches all the way back to the predawn of the NFL; Cincinnati’s goes back to 1968. A rivalry might have made sense geographically—the driving distance between Green Bay and Cincinnati is about the same as it is between Green Bay and Detroit—but the two teams play in different conferences and rarely encounter each other. Indeed, before they met at Lambeau Field at one o’clock on a sunny 53-degree afternoon on September 20, 1992, they had played each other in the regular season a grand total of six times in 34 years. There was nothing at all special about their week-three matchup, nothing to suggest that it would turn out to be one of the most consequential games in the history of the Packers.

Green Bay–Cincinnati seemed to be a game between one team on the rise and one that was stuck in the same old rut. The Bengals, coming off a 3–13 season, had jumped out to a 2–0 start and were seemingly ready to make some noise in the AFC Central Division. They had a new coach in David Shula. They were led by quarterback Boomer Esiason, the 1988 NFL MVP. The Packers, on the other hand, had been mired in bad for 24 years, stuck at the bottom of the NFL heap. And though they had a new general manager and a new head coach, things did not seem to be much different. Green Bay was 0–2 and was coming into the game off an ugly 31–3 loss to the lowly Buccaneers in Tampa Bay. With Green Bay trailing 17–0 at halftime, coach Mike Holmgren had benched quarterback Don Majkowski in favor of backup Brett Favre. After the game, Majkowski vented to reporters. “I didn’t agree with the switch,” he said. “I was very angry.”

To weary Packers fans, it looked like more of the same was in store in 1992. The Bengals game was a pick ’em on the betting line. That in itself seemed sort of like a victory. On Sunday morning, the marquee outside Motor Parts West, in Ashwaubenon, just a few blocks southeast of Lambeau Field, read, GO PACK. BEAT SOMEONE. ANYONE. PLEASE.

The game began slowly, with both teams pushing the ball harmlessly around the middle third of the field on their opening possessions. With about eight and a half minutes to go in the first quarter, on third-and-seven from the Packers’ 38, Majkowski dropped back to pass. As the pocket collapsed around him, Bengals defensive tackle Tim Krumrie grabbed hold of Majkowski’s left ankle and never let go, dragging the quarterback down to the turf. Majkowski fell forward in a twisting, slow-motion sort of collapse, then remained on the ground, writhing in pain. He had suffered torn ligaments in his ankle and had to be helped off the field by two trainers. Green Bay punted the ball away while Favre warmed up and talked on the phone with quarterbacks coach Steve Mariucci, who was up in the press box. Two plays later, Esiason threw an interception. The Brett Favre era in Green Bay had officially begun.

For the first 40 minutes or so, there was not much to distinguish it, not much for the 57,272 in the stands to cheer. Favre completed his first pass, to wide receiver Sterling Sharpe, and then played poorly. He fumbled four times, losing the ball twice. Forced into duty as the holder for kicker Chris Jacke because of the injury to Majkowski, he mishandled two snaps and was responsible for Jacke missing two of his three field goal attempts. Favre also called some the oddest formations that Holmgren had ever seen. At the end of three quarters, Cincinnati led 17–3 and seemed in control of the game. Green Bay scored its first touchdown when rookie cornerback Terrell Buckley—the player on whom the Packers had used the number-five pick in the 1992 draft—returned a punt 58 yards for a score 2:17 into the fourth quarter. The Bengals responded by driving for a field goal and a 20–10 lead with 8:05 left.

And then, all at once, Favre began to play with a real feel for the game, hitting the kinds of throws and playing with the kind of fearlessness that would define his career. He led the Packers on an 88-yard scoring drive, completing five of six passes for 67 yards and scrambling for another 19. The key play came with about six minutes left. On first down from the Green Bay 49, Sharpe lined up in the slot to Favre’s left. The receiver juked cornerback Rod Jones at the line and took off on a corner route. Favre took a five-step drop and lofted a beautiful ball that Sharpe caught in stride at the Bengals’ 28. Three plays later, Favre threw the first touchdown pass of his career, a five-yarder through traffic over the middle to Sharpe. The Packers trailed 20–17. Suddenly there was hope.

Green Bay stopped Cincinnati on the Bengals’ ensuing possession, but Buckley fumbled the punt and Cincinnati got the ball back on the Packers’ 36 with 3:11 left. Green Bay used up both of its remaining timeouts during the short drive that followed, which ended when Jim Breech kicked a 41-yard field goal with just over a minute to go. Cincinnati led 23–17 and seemed to have the game well in hand. The Bengals looked to be even more in control when rookie receiver Robert Brooks fielded a poor kickoff against the sideline and stepped out of bounds at the Green Bay eight-yard line. Had Brooks let the ball go, Cincinnati would have been penalized and the Packers would have had the ball on their own 35. As it was, with just 1:07 left, Favre had 92 yards to go and no way to stop the clock.

On first down, he threw out of his own end zone into the right flat to fullback Harry Sydney, who stepped out of bounds at the 11-yard line with 1:01 left. On second-and-seven, Favre dropped straight back, looked over the middle to tight end Jackie Harris, and then threw long down the right sideline to Sharpe, over the head of Jones. The ball was slightly above and behind Sharpe, who twisted to his left as he extended himself to make the catch and then kept twisting around as he fell forward. He came down on top of the ball at the Bengals’ 46. Sharpe got up clutching his midsection. He had suffered broken ribs. Nobody was really paying attention, though. Favre was hustling the Packers to the line and the clock was still running: 45 seconds, 44, 43 . . .

With 34 seconds left, center James Campen snapped the ball to Favre, who threw over the middle to running back Vince Workman for 11 yards. The situation on the field was frantic. Green Bay again rushed to the line and Favre spiked the ball with 19 seconds to go. He looked like he was out of breath. Sharpe, doubled over in pain, screamed at Holmgren to take him out. The coach subbed in Kitrick Taylor, a journeyman receiver from Washington State. The speedy Taylor was primarily a special teams player for the Packers. He entered the game with all of 33 career receptions— none of them for a touchdown.

Favre did not know any better, though. The call for the next play was “all go,” with Green Bay’s three wideouts sprinting straight toward the end zone. But Favre didn’t put up a Hail Mary. He dropped five steps, looked over the middle to Harris, and pump-faked a throw to him, freezing free safety Fernandus Vinson. Favre then looked back to his right, stepped up in the pocket, and unleashed a bullet in the direction of Taylor, who was streaking all alone ahead of Jones down the right sideline. The throw was perfect. Taylor caught the ball in stride over his left shoulder at the one-yard line. Vinson, who had bitten on Favre’s pump fake, was closing in, but, like Jones, he was behind the ball. He was helpless. Touchdown. Lambeau Field erupted.

Favre ripped off his helmet and, holding it by the face mask in his right hand, thrust both arms into the air in celebration. He ran around the field slapping his linemen on the shoulder pads. He squatted down on the turf, overcome with emotion, burying his face for just a second in his left hand. He held for Jacke’s extra point in bizarre fashion, balancing the ball on its point and then taking his hands off it completely. Jacke made the kick anyway and Green Bay won 24–23. The sound inside Lambeau was one loud, long, deafening roar—equal parts exultation and relief. It was a sound 24 years in the making.

Favre was not the only Packer who was emotionally spent. Campen was crying. In the north end zone, Lombardi-era linemen Jerry Kramer and Fuzzy Thurston—on the sidelines with a host of other former Packers for an alumni reunion—embraced in celebration. Holmgren described the victory, his first as an NFL coach, as “the happiest win of my life.”

There would be many more to come, but this was the starting point. All the hallmarks of Brett Favre’s long and glorious career were there. The fearlessness and brilliance, the questionable decision-making and boneheaded plays, and the thunderbolt right arm that made throws no other quarterback could make. A new era had officially begun. “Favre threw that pass,” says general manager Ron Wolf, “and everything changed.”