The 49ers Are a New Take on a Classic Team

Kyle Shanahan began the Tuesday-morning meeting by calling out his leaders. Joe Staley, the veteran tackle and offensive team captain, defensive co-captains DeForest Buckner and Richard Sherman, and leading rusher Matt Breida were all told that they disappointed during the previous night’s loss.

Then, before players broke out into position groups for a full film breakdown, Shanahan delivered one more message, this one to a struggling young player. He referenced a play on which Giants receiver Sterling Shepard takes a reverse 27 yards downfield, sidestepping a lackadaisical shove from Niners cornerback Ahkello Witherspoon on his way out-of-bounds. I’ve defended you for over a year and a half, Shanahan told Witherspoon, according to several people who were in the room. We need to have a standard if we’re going to do what we need to do, and this doesn’t meet that standard. This is unacceptable.

That was the second week of November 2018, 10 games into what would end up a four-win campaign. After a loss to the previously one-win Giants—at home on a Monday night—the 49ers were sitting at 2–8. There was a theory pervasive in the building that the Niners were very close to turning things around. A return to health for an injury-ravaged roster (at that point starting its third-string QB), plus another offseason of draft and development, would get them there. But Shanahan saw the cracks beginning to form. The message he was sending in that meeting was clear: The turnaround was never going to happen with the level of effort being put forth.

One year later, effort is not a problem. In fact, there are few issues to be found during a season that has played out exactly as planned. The Niners were the last unbeaten team in the NFL, but they won’t talk about it—at Shanahan’s direction, his entire coaching staff declined to speak with Sports Illustrated for this story. (“I think Kyle feels like we haven’t done s--- yet,” one veteran player says, “and that’s fair.”) But those within the locker room see something undeniably special happening for a storied franchise emerging from a half-decade of struggle. There are the things anyone can see, like the quarterback’s return to health, or the aggressive acquisitions that upgraded the roster, most notably game-changing rookie edge rusher Nick Bosa. There are the things you can see if you watch closely on Sundays, like the unprecedented schematic twists incorporated into a trendy defensive scheme or the modernized remix of the classic offensive system. And there are the things no one outside the building realizes are going on, the old-school sensibilities, the updated approach to management and scouting, and Shanahan’s willingness to confront issues—some his own making—that festered throughout two losing seasons. The result is a team short on household names with low expectations outside their own building rising to the top of the new NFL, and perhaps along the way becoming the league’s latest prototype for greatness.

* * *

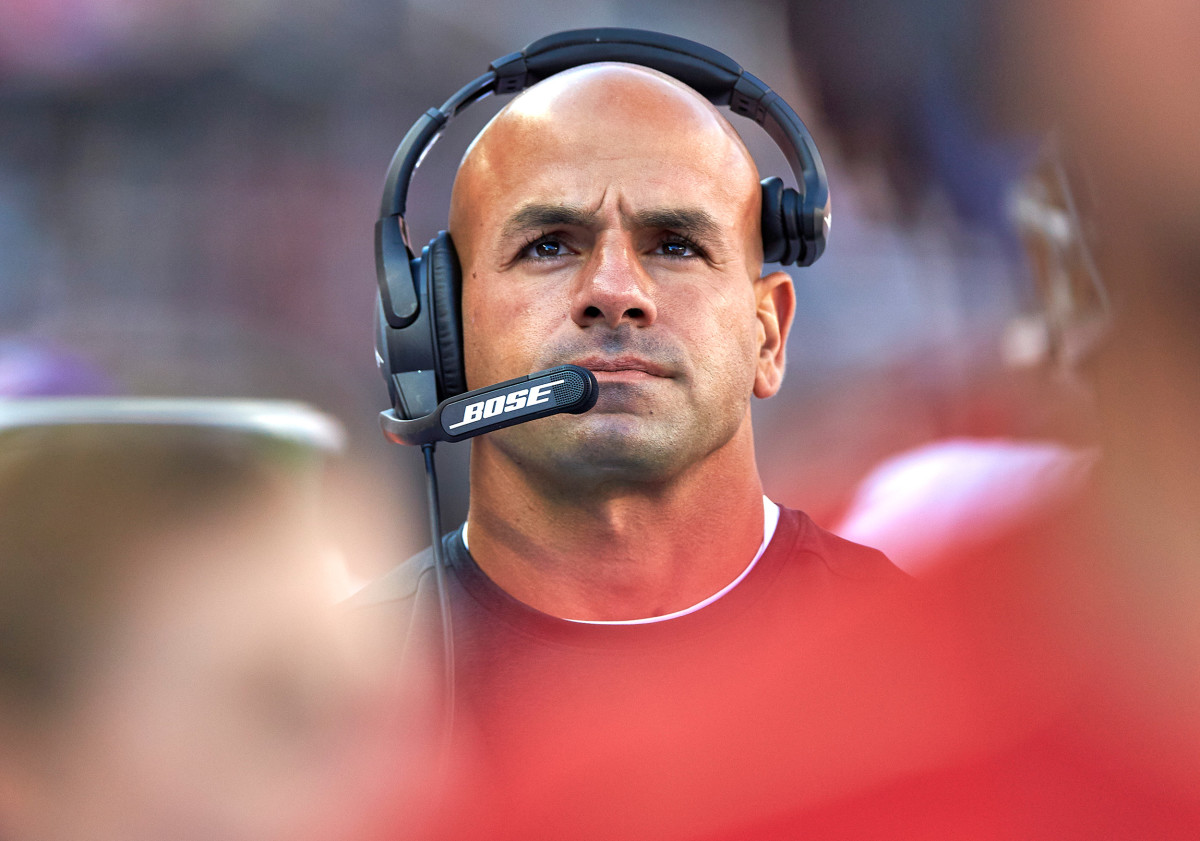

Over three seasons, Shanahan has brought in a stable of coaches he had worked with in Washington, where he spent four seasons as offensive coordinator under his father, Mike—run-game coordinator Mike McDaniel, running backs coach Bobby Turner, game-planning analyst Chris Foerster, offensive assistant Bobby Slowik and special teams coordinator Richard Hightower among them. Yet three years ago, he went outside his network for his most important hire: defensive coordinator. Robert Saleh, then the Jaguars’ linebackers coach, had grown popular in league circles, and now his name has vaulted to the top of many head coach candidate lists.

Saleh’s journey to the NFL began on Sept. 11, 2001, when he was a 22-year-old former Northern Michigan tight end starting a job at Comerica Bank in Detroit. His oldest brother, David, was beginning his second day of intensive training as a financial adviser with his new employer, Morgan Stanley, in New York City. David was evacuating the South Tower when United Airlines Flight 175 struck it. He made it out safely and, with air traffic grounded, found a ride home to Dearborn, Mich., reuniting with his family.

Robert returned to work at Comerica, stunned. He went through the motions as a first-year credit analyst for a commercial lending department, but his mind raced as he contemplated the fragility of his brother’s life, and of his own. He began thinking about his purpose, about what he wanted to do with his life. He chose football. Beginning at Michigan State in 2002, he embarked on the humbling path of a gopher for a handful of college programs before getting his big break as an intern for the Houston Texans in ’05.

He shares the demeanor of the two head coaches he had most recently worked under—the Seahawks’ Pete Carroll and former Jaguars coach Gus Bradley: enthusiastic and relentless.

“He approaches every day like that, literally every day,” linebacker Kwon Alexander says. “He keeps the game simple, he doesn’t dwell on one thing. Keeps the energy going.”

But Saleh had work to do coming into this fall. In 2018 the 49ers ranked 28th in the NFL in points allowed. Never in the history of the league had a team had fewer than 11 takeaways in a season until the 49ers had just seven last season. They needed an upgrade in talent, but they also needed to alter their scheme.

General manager John Lynch did his part to boost the defense in the offseason. In March he traded a 2020 second-round pick for Chiefs Pro Bowl edge rusher Dee Ford. He also found a stabilizing force in free agent Alexander, the former Bucs linebacker. But the biggest acquisition came in last year’s draft, with the selection of Bosa second overall. Halfway into the 2019 season, Bosa is running away with the league’s Defensive Rookie of the Year award. He’s played so well that he’s warranting mention in midseason Defensive Player of the Year discussions. And it was some unprecedented adjustments to the scheme that unleashed the best in Bosa.

Saleh’s background is in the Cover 3 defense the Seahawks perfected during their Legion of Boom years. The term Cover 3 comes from the use of the defensive backs, a staple zone coverage in which the two outside cornerbacks and a safety are each responsible for one-third of the deep field. The defensive game plan is exceedingly simple, players say, especially on the front seven. Solomon Thomas says the playbook for defensive linemen is about half of what he had at Stanford. The simplicity helps the linebackers play fast—the rangy Alexander proved to be a perfect fit. Saleh’s front seven has been more confident and competent in 2019—last year’s tackling woes, a common talking point among Saleh’s local critics, have all but disappeared.

The cornerbacks, who each typically stick to one side of the field rather than traveling with specific receivers, develop nuanced techniques specific to that side, much like offensive tackles do on the other side of the ball. And the back end is where things get complicated, especially for the safeties. As Carroll’s coaching tree branched out and more defenses began using the Cover 3 across the league, offenses figured out that over routes—a receiver runs a deep crossing route arching to the opposite side of the field—typically put Cover 3 defensive backs in a difficult bind. To counter that, the 49ers will often morph into a Cover 4 look after the snap (four defensive backs dropping across the back of the defense). It takes a high level of communication and chemistry in the secondary to do it right, and San Francisco has just that—starting safeties Jimmie Ward and Jaquiski Tartt were high school teammates, and Sherman adds another veteran presence.

But Saleh’s system needs a pass rush; it not only takes pressure off the back end, cutting into the time they have to cover opposing receivers, but it also forces quarterbacks to play uncomfortably fast. Since his defensive backs are often facing the line of scrimmage rather than turning their backs and running with receivers like they would in a scheme heavy on man coverage, pressure can lead to a high rate of takeaways. To maximize the pass rush, Saleh and defensive line coach Kris Kocurek came up with a new twist on the Seattle-style defense.

San Francisco now pairs the Cover 3 with a Wide-9 alignment on the defensive line. That means the ends line up well outside the offensive tackles and are tasked with simply attacking and crashing toward the ball, the wide alignment allowing them to build up a head of steam along the way. It’s a schematic combination unique to these Niners, and it’s working. Through eight games they ranked first in the NFL in Football Outsiders’ “adjusted sack rate” metric, a more complete measure of pass rush that takes into account not only sacks but also intentional grounding penalties per pass attempt, adjusted for down, distance and opponent. At the midway point of the season, San Francisco was one of four defenses averaging two or more takeaways per game. And after picking off two passes all of last season—also an NFL‑record low—the chaos created by the new approach led to 10 interceptions in their first eight games.

The energized pass rush has been more than just the two newcomers. Seven defensive linemen have earned more than a 25% share of defensive-line snaps, a group, which includes four first-round picks, including Pro Bowl defensive tackle DeForest Buckner. The players up front are talented, fresh, and supremely aggressive due to the scheme.

If Saleh has a player cohort in the motivation department it’s Sherman, who was a rookie in Seattle when Saleh started under Carroll as a defensive quality control coach in 2011. At 31, and two years removed from what was—because of his age—perceived to be a career-threatening ruptured Achilles, Sherman is again playing at an All-Pro level. At least one teammate calls Sherman “the Spokesman.” He’s been the welcome wagon, reaching out to newly acquired players like Emmanuel Sanders with advice on housing. He tells teammates in private moments, You’re playing great, but to be legendary, you’ve got to be consistent, relentless.

* * *

The turnaround is actually coming a year later than anticipated. Last season was supposed to be the 49ers’ revival, led by Jimmy Garoppolo, the kind of franchise quarterback thought to be a prerequisite for winning football in the modern NFL. But at the midpoint of the season, the passing offense ranks in the bottom half of the league.

What’s fueling the 49ers on the offensive side of the ball is a system built around the running game. They are the first team in a decade—and one of just five since 1990—to eclipse 300 rushing attempts over the first eight games of a season. It’s a mark that teams coached by Kyle’s father, Mike, whose zone-rushing attacks in Denver set the standard for the scheme and helped the Broncos to two Super Bowls, never hit. But Kyle is bringing an extreme version of a classic blueprint into the modern era.

In a league where single-back sets are now the norm, no team over the past two seasons has trotted out 21 personnel—two running backs, a tight end, and two wide receivers—as frequently as the 49ers. The zone-running, play-action-heavy offense it portends is a response to the changing nature of the NFL, players say.

The emphasis on speedy edge rushers across the league—more athletic but much leaner than opposing offensive linemen—is being punished by the 49ers. Teams growing more accustomed to fielding two linebackers and five defensive backs (intended to counter the proliferation of spread offenses) find themselves benching well-compensated third cornerbacks and playing seldom-used third linebackers against San Francisco. And because teams face 21 personnel far less than three- and four-receiver sets during the rest of the season, opponents have fewer defensive looks they can show them. The 49ers don’t quite have all the answers to the test, but they’ve narrowed down the options significantly.

“It’s not really [new],” says Staley. “It’s just old fashion that comes back in vogue. We start to feel like we control what the defense can do because they have to play certain fronts and coverages. The way the NFL is now, the guys on the edge come out of college fast as hell, and offensive linemen are just at a disadvantage going one-on-one with them, so Kyle creates advantages for the offensive line because they’re thinking about play-action and stopping the run.”

A stable of game-breaking backs ramps up the pressure on defenses. Tevin Coleman, who played for Shanahan when the coach was the offensive coordinator of the high-scoring 2016 Falcons, joined Breida and Raheem Mostert in the backfield rotation. Each has a touchdown run of at least 40 yards this season. All-Pro tight end George Kittle and versatile fullback Kyle Juszczyk (originally listed as “offensive weapon” on the team’s roster after signing during the ’17 offseason) provide more headaches for defenses that must use heavier personnel to counter them but risk getting burned in the play-action game if the personnel they use is too slow.

And while other coaches and front-office types across the league lament the quality of today’s draft-eligible offensive linemen, Shanahan and Lynch have hardly bothered with them. Just two of their 27 picks since Shanahan joined the team in 2017 have addressed the front five. (During that span, San Francisco has drafted four linebackers, five defensive linemen and seven receivers and tight ends.) And the linemen the 49ers have drafted, traded for or signed in free agency all have one thing in common: “We don’t have any big, fat-body guys,” says center Weston Richburg, a 2018 free agency pickup.

One of those two drafted offensive linemen, rookie sixth-rounder Justin Skule, has stepped in for Staley since Week 2, when Staley suffered a broken left leg. Skule was Pro Football Focus’s 11th-highest-graded run blocker through eight games. At Vanderbilt’s pro day in March, his 7.54-second performance in the three-cone drill (an exercise that measures agility in a confined space) would have ranked sixth among ’19 NFL combine participants—had he been among the 57 offensive linemen deemed worthy of an invite.

“Kyle doesn’t put us in a position where you’re playing seven-on-seven and hoping your offensive line stands up,” Staley says. “It’s all about efficiency on first and second down. Kyle does a great job of combatting all the speed on defense and making the defense play the way we want to.”

The uniqueness of the scheme is one advantage, and it’s augmented by Shanahan’s aptitude as a play-caller, especially when deploying a game plan’s opening script.

“The first 15 plays becomes about understanding the way the defense wants to attack us,” Staley says. “Kyle is a beautiful mind with all this stuff. He doesn’t even have a call sheet, really. He just pieces it together with his mind and calls it.”

* * *

Some of the team’s success is surely linked to one of the more radical changes Shanahan has made since arriving. Newcomers say the 49ers’ practice time is among the shortest in the NFL. At first glance, San Francisco’s newfound brand of physical football seems to stand in sharp contrast with practices that average one hour and 45 minutes and only see players strap on shoulder pads for half a practice, on Thursdays.

“Old-school coaches say, You need to be tough!” says Ford. “F--- outta here. You don’t forget how to hit. Either you’ve got physical players or you don’t. We’re one of the more physical teams in the league, and we probably wear pads less than anybody.”

There are also bonuses that might not show up when watching game film in a vacuum. “Morale, emotional stability, energy, focus,” Ford says. “More is not more. [Shorter practices are] not what the old-school guys are used to, but that’s why you see a lot of guys leave the game in bad shape. Games are not the problem in this sport. It’s the week, the cumulative effect.”

What the practices lack in duration they make up for in speed. Transitions between plays and periods are fast. There’s no time for coaches to launch into long-winded teaching moments. Mistakes are corrected in the film room. Practice is a 40-yard dash instead of a mile run. “When it’s fast like that, we pick up stuff like this,” Alexander says as he snaps fingers rapidly. “Then when you get to the game, it starts to feel like slow motion.”

Coleman, another first-year Niner, says practices in San Francisco are about an hour shorter than the ones he experienced playing in Atlanta. “Guys get on their details,” he says. “At first it was overwhelming. It helps us as we get in the game. The game just seems slower.”

What time the players don’t spend on the practice field, they spend in recovery. The Niners staff a small army of masseuses, chiropractors and acupuncturists, many of whom travel with the team. “That might not be rare around the league now,” Staley says, “but it definitely was when we started it.”

Overseeing it all is Ben Peterson, former director of sports science for the NHL’s Philadelphia Flyers and now head of player health and performance for the Niners, a position created out of a need for harmony between the athletic training staff and the strength and conditioning staff. After two injury-plagued seasons that included, according to two team sources, various miscommunications between the two groups, the team fired strength and conditioning coach Ray Wright and athletic trainer Jeff Ferguson last winter.

Standing adjacent to the practice field, just to the right of the path players take from the locker room, is a 20-plus-foot artificial hill at a steep incline and covered in artificial turf. It was ordered by Wright, and players once ran up and down the hill frequently. Now it stands unused and fenced off, a failed experiment turned monument to accountability.

* * *

At least some acrimony was to be expected in the nascent days of what was, in 2017, the most inexperienced owner/GM/head coach combo in football. Jed York, the 39-year-old CEO, hired Lynch, the former Buccaneers and Broncos safety, in his first general manager gig after a stint in the broadcast booth. Shanahan was 37 when he took the job.

In July, Bleacher Report quoted numerous anonymous Niners scouting sources who testified to a disconnect between Shanahan and the front office and scouting staff, which spoke to a shift of philosophies from one regime to another. During former GM Trent Baalke’s run, as the popular NFL idiom goes, the general manager and his scouting staff shopped for the groceries and the coaches made dinner. But the offense Shanahan and McDaniel installed, and the defense Saleh brought with him, are among the most nuanced schemes in the NFL. Shanahan and McDaniel, the run-game coordinator, especially, took the reins in the draft war room, with McDaniel and Saleh standing on the table for certain prospects, and Shanahan and Lynch making the final call without—some scouts felt—much input from the scouting department. In light of that, having scouts in the team meetings with an open invitation to join position-group meetings serves another purpose.

Those team meetings can be stressful, as Witherspoon experienced. Staffers, including front-office execs, scouts and heads from football departments including the pro personnel group, athletic training and media relations, are invited to watch Shanahan break down film. It was a measure taken by Lynch and Shanahan to keep messaging consistent, add accountability to the film session and educate personnel people on what players are being asked to do every day. “It’s like, if you don’t want the whole staff to see it, don’t even put it on film,” Witherspoon says. And Shanahan is more apt to place a portion of blame for a loss on a missed cut block on an anonymous first-half drive than a blown coverage on the game-winning touchdown.

In more intentional ways, Shanahan and his staff have fostered a fun, family-friendly atmosphere while keeping accountability at the forefront. During open media periods, the locker room takes on a raucous environment, with players enjoying cranked-up hip-hop played from a digital jukebox installed on a wall and reporters dodging basketballs that clank off a hoop installed high atop a center cluster of lockers.

“Humanity,” says Sherman. “Some coaches coach as if they’re not flawed in any way. Pete [Carroll] does a good job of showing humility. Kyle will say, I messed up here, this guy messed up here, and this is why we lost. He doesn’t talk above or below you, he just talks to you. Guys respect that.”

Sherman understands why Shanahan grew upset in those film reviews, but he also understood why the faith in that locker room was so high when the NFL world was down on the Niners. “Because I saw what we could’ve been before we got beat to s---,” Sherman says. “We were in every game with the third-string quarterback and a lot of practice squad and third-string guys on the field. We were Monday night in Lambeau with a chance to win.

“It’s not some magic formula. It’s consistency, dependability, accountability. It’s knowing you’re one of 11 and just being responsible for being one of 11 and not feeling like you have to do more. It’s not being impressed by moments.”

There are challenges ahead. The 49ers played one of football’s easier schedules in the first half of the season, and the NFC has proved to be the much deeper of the two conferences. With All-Pro tight end George Kittle sidelined and top receiver Sanders injured during the game, they suffered their first loss of the season Monday night, in overtime to the rival Seahawks at home. And they’ll have to navigate the entire second half of 2019 without Alexander, who suffered a season-ending pectoral injury in Week 9.

In another film session last season, Witherspoon recalls being among those called out by Shanahan. “If I had anybody behind some of you, I’d cut you,” the coach said, addressing a few players, according to the cornerback. “Next year we’re not going to be in a position where we have any of this bulls---.” As Witherspoon reflects on his coach’s reaction, he understands it as well now as he did then: “I couldn’t really argue,” he says. “It comes with the responsibility of having the potential to be great.”

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.