Albert Haynesworth Doesn’t Need Your Love. Just Your Kidney

The first time Albert Haynesworth almost died, on Halloween 2014, he woke up in the middle of the night, his head jackhammering, and slammed an entire pack of extra-strength pain-relief powder. He couldn’t see straight and lost his balance. Concerned, he wandered his house, dialing his ex-wife and texting a cardiologist friend. Finally, at sunrise, he left for the emergency room, wearing sunglasses to blunt the painful light. When he arrived, he needed assistance inching down the entryway.

“Send him home,” one doctor suggested. “He’s got a migraine.”

Haynesworth’s cardiologist friend intervened. “I know this guy,” he said of the retired defensive tackle, a two-time All Pro. “He can handle pain.”

Immediately Haynesworth underwent a battery of tests. He’d forgotten how to sign his own name and struggled to spell the simplest words. Examiners plunged a long, thin needle into his lower back for a spinal tap, and blood spurted right back out. “Oh, man,” one doctor said. “This is not good.”

The diagnosis confirmed that Haynesworth could indeed handle extreme pain. He’d suffered not one but two brain aneurysms, his blood vessels swelling and then leaking inside his skull. Emergency surgery ensued. Doctors told Haynesworth they would put coils inside his brain to stop the blood vessels from expanding. When that failed, they added a stent.

In the end, Haynesworth stayed in intensive care for 11 days, confined to a hospital bed, where all he could think was, Damn, I guess that’s what death feels like.

* * *

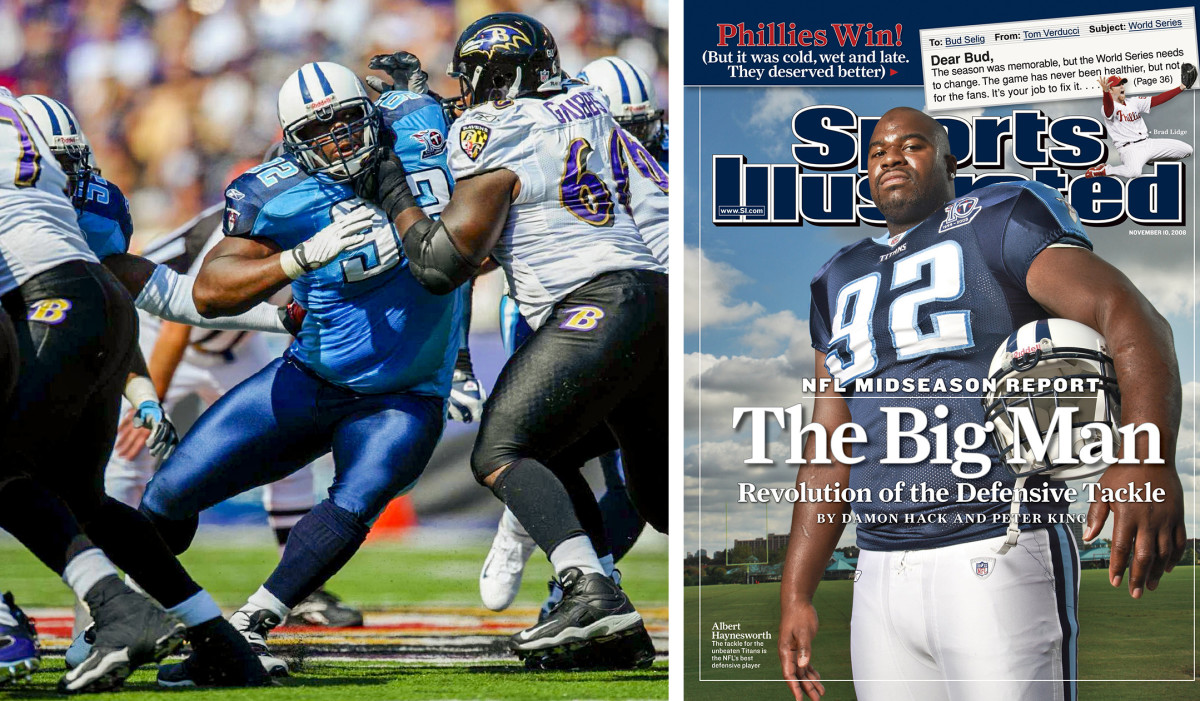

How do you remember Albert Haynesworth? Feared defensive lineman at the University of Tennessee? First-round pick by the Titans in 2002, perhaps the last player in blue-and-navy-and-red-and-silver (so many colors) to instill the worst kind of fear in opponents? Free-agency megabenefactor—the first defensive player to sign a $100 million contract—and then a statistical letdown with the Redskins?

Haynesworth was all those things. But none of them is the thing for which he’s most remembered.

This past Halloween, eight years out of football at age 38, down some 65 pounds from his playing weight of 340, he decided to dress up. He pulled on his old jersey and some pads he found lying around his apartment in Franklin, Tenn., and he went out as . . . himself. And on this day, more than most, he heard the whispers. “People were like, You’re the guy that kicked that dude in the head,” he says, referring to a ghastly on-field incident in 2006 that now makes up a quarter of Haynesworth’s Wikipedia biography.

“Yeah, that was me,” he responded, same as always, not ashamed.

It wasn’t so long ago, shortly before his aneurysms, that Haynesworth was entertaining a comeback. He’d left the game in 2011 with a broken body, internal and external scars, and a tarnished reputation. But he was ready to reboot—until his ER visit forever ended that possibility. “If you’d come in a couple hours later, you wouldn’t be here,” his doctor had told him, adding that it would be dangerous to ever again lift more than 25 pounds above his head. He still scrambles words occasionally. Even his own name.

Shortly after that diagnosis became public, an old rival called. Former Bears defensive tackle Tommie Harris, whose own wife had died of a brain aneurysm two years earlier, when she was 29, remembers viewing Haynesworth the way much of the world had, as an NFL villain who lost all decency on the field. Still, he invited Haynesworth to a charity gala, seating himself at the same banquet table. There, Harris says, “everything I’d ever felt against Albert crumbled away.”

“It’s crazy how pain can bring people together,” says Harris. “Football hides what it means to be normal, but in that moment it was two warriors sitting down without their armor or swords.”

Haynesworth never saw the empathy coming. He’d long ago accepted the popular perception of him; he didn’t expect a health scare to change how anyone viewed his darkest moment or to feel differently about the ungodly amount of money he’d earned. “I’ve always been the same guy,” he says.

But here he started to see how the humanity of his football afterlife—his public health problems on top of his financial ruin—altered people’s feelings. He hadn’t asked Harris for forgiveness, but Harris had forgiven him. “What we’re seeing now,” says the old Bears Pro Bowler, “is Albert in a place of vulnerability.”

Haynesworth’s is not some neat and tidy narrative. This isn’t simply: Man becomes villain/villain nearly dies/mortality leads man to change/public embraces changed man. Today Haynesworth does need considerable medical assistance, and the lens through which he is viewed has changed, but his story isn’t redemptive. It’s full of contradictions and close calls and ambiguities. It speaks to fame and fortune and forgiveness and, of course, football, in both the violence that is expected in it and in the lines players cross.

* * *

It’s happy hour, and so Haynesworth points his white Hyundai Genesis toward his new happy place: a low-key watering hole just south of Nashville called the Tin Roof. He’s headed to meet an old teammate, Titans linebacker Keith Bulluck, with whom he’ll reminisce about the NFL and the demons players must summon every week, trading sanity for glory. For so many years, football was their happy place and their dark place all at once.

Before the first drink is even poured the men are telling stories, like the one about Haynesworth’s rookie season, when he arrived in training camp following a short holdout and got jumped by offensive players after practice, their punches and kicks battering his ribs. In a way, those were simpler days. Just football. Haynesworth grew to love his position coach, the salty Jim Washburn (the type of guy who showed players Deliverance for inspiration) and to laugh at the profanity-laced tirades of his coordinator, Jim Schwartz. His defensive teammates—Bulluck and Adam (Pacman) Jones and Jevon (the Freak) Kearse—called themselves the Tennessee Tyrants, and they carried that ethos into games. Tough, uncaring, violent.

Few embraced that philosophy more than Haynesworth, who Washburn calls a “planet guy,” meaning there aren’t many like him on this Earth: 6' 6", 300-plus pounds, with a 5.09 40 time at the combine. He delivered force with his mass-times-acceleration and never felt bad about the damage he inflicted. It was part of the job and, if he’s being honest, part of the thrill.

Haynesworth’s previous coaches had warned Washburn. They said there were lines he tried not to cross but had often tripped right over. They called him headstrong and confrontational, and they lamented his poor attitude. It couldn’t have been a huge surprise, therefore, when Haynesworth kicked a teammate in one Titans practice, for example, or later when he started an altercation at the Pro Bowl, which Peyton Manning broke up.

Even then, the man The Sporting News named its Defensive Player of the Year in 2008 seemed worth the headaches. Mostly. He wrecked double teams and helped the Titans collapse pockets without blitzing, turning the defense into a force and the franchise into a legit playoff contender. The last time anyone outside Nashville cared about the Titans, Haynesworth was their combustible reactor core.

Washburn, meanwhile, calls Haynesworth “maybe the smartest football player I’ve ever been around. Brilliant.” But that’s not how he’s remembered. In some ways his greatest strength—his terrifying, imposing, rip-out-your-will force—painted an incomplete picture, made him appear a brooding brute, nothing more.

Bulluck remembers the time his friend leaped over a lineman “like f------ Frogger.” Or the time he moved Hall of Fame Cowboys guard Larry Allen as if he were pushing a stroller. It was “like watching the Hulk when the Hulk smashes,” Bulluck says.

Indeed, Haynesworth hulked out on Sundays, channeling his rage into collisions. He’d pregame by watching violent movies like Man on Fire, where everybody ends up dead; then coaches knew not to talk to him. He’d boil and boil until his eyes burned and his skin tingled. He remembers feeling an addictive power surging through his body as the national anthem played. He didn’t just want to win, he wanted to know that the man across from him—who had family in the stands, who was a hero to his children—acknowledged Albert Haynesworth was better and stronger. “I got off on that power, the high,” he says. “It took me to dark places. Desensitized me.”

Haynesworth embraced the most violent parts of football. He was paid to inflict maximum pain, and the more he inflicted, the more teams tripped over themselves, rushing to hand him buckets of cash.

“He was a f------ savage,” says Bulluck.

Haynesworth: “Like, if [an opponent] wanted, we’d meet in the parking lot afterward.”

Bulluck: “In our sport, at the highest level, you have to go to that place.”

Haynesworth: “I was there.”

* * *

The event for which many will never forgive Albert Haynesworth came on Oct. 1, 2006. Cowboys guard Andre Gurode was the man tasked with standing across from him that afternoon, and the trouble started, in Haynesworth’s telling, when Gurode clipped his knees from behind and boasted, “I’m trying to put your ass out.” Haynesworth says he saw red from that point on. He remembers a coach yelling from the sideline, “You better kill that mother------!”

“And then it was just like a switch,” Haynesworth says. “I can’t remember.”

What he does remember is late in the game coming into the Titans’ home locker room, empty except for an equipment staffer, and seeing himself on an endless TV replay loop. There he was, pushing off Gurode’s helmet following a Cowboys rushing touchdown, right leg raising off the ground and stabbing downward purposefully and forcefully into the lineman’s face. In the locker room, all Haynesworth could think was, Oh, s---. I lost it.

Gurode has his own memories. He says today that the injury at first felt like a scratch, even though he knew he’d been stepped on; even though he could feel blood gushing into his eye, blurring his vision. When he realized what had happened he says his next instinct was to attack Haynesworth, but when he tried to stand up he could feel a weight pushing him back down. He looked into that later, watched the replay on TV, and saw no one. His interpretation, which he still believes: This was God at work, giving him the strength of calm.

God was no help with the pain, though. Team doctors applied a numbing agent through a needle and threaded 30 stitches into Gurode’s cheek. He wanted to return to the game (but did not). He wanted to talk to Haynesworth, to understand. He wanted—even on the flight home, as his head throbbed like he’d been “hit by a baseball bat on both sides at the same time”—to take his attacker to church.

Gurode says he reached Haynesworth a day later and asked, “Man, what did I do to you?”

“You didn’t do anything,” replied Haynesworth, who did publicly express immediate remorse. Who did apologize. Who did accept without appeal or complaint the NFL’s five-game suspension, at the time the longest ever for an on-field incident.

Haynesworth says he knew even then that he’d spend the rest of his life trying to live down that moment. What he didn’t yet know was how it would benefit him. Back on the field he saw fear in linemen’s eyes, saw elite players avoid him or shy away from contact. The net effect, he says: The incident elevated his play to another level, and that only complicates his feelings as he looks back. He crossed a line in unprecedented fashion. He deserved everything that everybody said about him. He felt terrible. And yet the stomp made him stronger, too.

Did he want forgiveness? Not more than he wanted to win a Super Bowl. Not then, when everything still seemed possible. Before it all fell apart.

* * *

Seated at lunch in a bistro outside Nashville, Haynesworth has a clear view of the ESPN ticker on the TV overhead, and the headlines are small reminders of his former life. Bengals quarterback Andy Dalton is being benched. . . . Rams cornerback Aqib Talib is being traded. . . . Tackle Trent Williams is beefing with the Redskins.

For Haynesworth, that last one is all too relatable. Trampling Gurode’s face may have established his reputation, but two disastrous seasons in Washington cemented his status as an NFL heel. He doesn’t blame the entire Redskins organization for that failed tenure. In fact, he says what almost no one else says: He loved owner Daniel Snyder, “a billionaire fantasy footballer” who wasn’t afraid to spend money and who wanted desperately to win.

A fat free-agent haul in February 2009—seven years, $100 million, with $41 million guaranteed—surely factors into Haynesworth’s warm feelings, though he insists his departure from Tennessee was about more than cash. Former Skins teammate Chris Cooley told a D.C. radio station in ’13 that Haynesworth’s “goal from the get-go was to take that money,” to which the defensive tackle responds that he left $35 million on the table in a richer offer from the Buccaneers. He says he wanted to boost his national profile in a larger market, start fresh, carve out the second act in what he hoped would be a Hall of Fame career.

When that didn’t happen, he blamed his fall on the man he calls “a conniving little liar,” coach Mike Shanahan, who joined the Redskins one year after Haynesworth. “If I was older,” he says, “I’d punch him in his face.” Haynesworth laughs uneasily. “I’ll get one of my uncles to kick his ass.”

He says he knew he was in trouble at Shanahan’s first practice. In Tennessee, Haynesworth had been what he calls “a racehorse,” free to wreak havoc and rush the passer. In Washington, things changed; his first season with the Redskins felt like playing with a plow affixed to his back, with new responsibilities, certain gaps he had to fill. Under Shanahan, he says, that felt like three plows.

The way Haynesworth tells it, the new coach had promised a scheme more like Tennessee’s, but now he was asking the lineman to “grab the center” and “use that wide frame to eat up space.”

“Can I be frank?” Haynesworth says he asked.

“Of course,” Shanahan said.

“You’re paying me all this money to do that?”

“Albert,” he says the coach replied, “if you have more than one sack this season, I’ll be pissed.” (Shanahan, now 67, declined to comment for this story. He says he wishes Haynesworth well.)

Haynesworth’s D.C. stay somehow got worse. He says Shanahan sprung a preseason conditioning test on him, which he failed and then passed, after a bathroom break—only Shanahan deemed the break too long and demanded a redo, which Haynesworth again failed. Haynesworth believes Shanahan leaked that story to the press.

Then the season started. That Haynesworth’s stats didn’t live up to his salary was only compounded by, for example, a now-famous clip of him falling to the ground in the middle of a play, or a well-told story about the time he asked for a cart off the field, then returned a short time later. Through this, Haynesworth says, he implored Shanahan to trade him, but the coach only laughed, joking about how he’d buy Haynesworth’s condo off him at a discount. “You’re talking about a cunning, manipulative person,” Haynesworth says.

Whatever happened—“a soap opera, man; ridiculous,” Haynesworth says—the D-lineman views himself as much a victim in Washington as Gurode was a victim in the stomping incident. And yet he assigns no significance to either, really, in terms of personal growth. He was wrong in one, wronged in the other. Both affected his reputation. Neither changed the man.

Haynesworth played one more season, split between New England and Tampa Bay, and he called Washburn, begging his old coach to take him back. But it was too late. For the turn his career had taken he blamed everyone except himself, everything except what he’d done.

* * *

The second time Albert Haynesworth almost died, at his apartment this past summer, he started coughing violently around 2 a.m. and lost his breath, barely able to draw in air. As he grew dizzy he decided to drive himself to the hospital—“I definitely should have taken an ambulance,” he says—and there learned his lungs had filled with so much fluid that oxygen couldn’t traverse his airways. His stomach, engorged by the same fluid, had bloated as if he’d swallowed a basketball.

Doctors immediately started Haynesworth on regular dialysis therapy, which today he undergoes three times a week at a treatment center, starting at 6:15 a.m. There he passes away the five-hour sessions watching CNN and Fox News (“to see what’s bulls---,” he says) and bingeing episodes of The First 48. He shares this cramped space with people from all backgrounds: white and black, young and old, successful and otherwise . . . diverse but depressingly the same, in that they each desperately need a kidney. Haynesworth’s doctors have made that clear to him. Even this mountainous man, once as feared as any in football, finds himself worrying about dying young, about all the graduations and weddings and milestones he would miss.

Haynesworth had another scare on Labor Day—the third time he almost died. He tried to set up dialysis at his home, but he took the wrong medication, he says, and landed back in the ICU, where the port in his stomach grew infected, extending his stay and worsening his condition.

In the three weeks it took to recover, Haynesworth had no A-ha! moment. Death had come knocking, but in no way had it forced him to look back or change dramatically. “I wouldn’t say I cheated death,” he says. “Just brushed with it.”

Still, the scare was impactful enough that his mother, Linda, moved into his Nashville apartment to help take care of him. Haynesworth says that these days he mostly feels good, close to normal—although his dialysis mates tell him he’ll be shocked at how he improves with a new kidney. Linda, meanwhile, bakes her son banana pudding, and they reminisce about all the strict rules she put upon Albert as he grew up in Hartsville, S.C. Rules that were supposed to keep him out of trouble, keep his reputation clean. Her son may be big and strong, he may not care about reputation and forgiveness, but he still needs the help, still needs his mom, who constantly reminds him to make his bed.

After one recent dialysis treatment, Albert came home and told Linda about a friend he’d made at the clinic, a man in his 40s. One day he’d been there, a needle stuck in his arm like everyone else. The next day he was gone, dead in his sleep.

This will repeat. Haynesworth lost another dialysis friend just last week. For him it was a reminder of the stakes, the risks he now confronts.

“You’ve got a lot of years to live, man,” a friend recently told him.

“I’ve got a lot to do,” Haynesworth responded.

* * *

Haynesworth pulls his Hyundai into the parking lot outside the gym at Brentwood Academy, an upscale Nashville private school populated by the scions of country music stars and famous NASCAR drivers—the types of people among whom he can easily disappear. Inside the gym Haynesworth’s 13-year-old son, Aivery, grapples with a larger opponent, long hair flopping, biceps flexing as Dad walks right up to the mat and shouts instructions: “You’re faster! You’re stronger! You ain’t tired! Show them who you are!”

When the lithe middle schooler wins easily, Albert wraps him in a bear hug. “[Your opponent] didn’t want it,” Haynesworth says, competitive as ever, unsoftened by age.

In his first few years out of football, Haynesworth spent most of his time in Florida, out on his boat, cigar clenched in his teeth, fishing rod in his hands. In between he’d drive another son, Ahsharri, now 18, to school or to football practice. For adrenaline he’d go rock crawling or gator hunting.

Post-football life was freeing, mostly. He stopped watching the sport, save for attending a few Volunteers games, where he felt loved. But love wasn’t what he longed for. If anything, he missed the idea of sauntering into a stadium, inducing fear, drawing energy from the crowd’s venom. He missed dominating his foes, how that made him feel. He didn’t miss the spotlight. But the spotlight found him.

Beyond the health scares there were speeding tickets and a public feud with an ex-girlfriend, Brittany Jackson, which in 2017 spilled into TMZ territory, with Haynesworth describing racist attacks and physical abuse. (Jackson denied those claims.) Before that there was an assault charge (later dropped), a road rage incident outside D.C. (dismissed) and a no-contest plea to a sexual assault charge for groping a Washington waitress (which Haynesworth denied). There were child-support disputes brought on by several women, and a high-speed Ferrari crash that partially paralyzed another driver. And there was the financial adviser who Haynesworth says stole most of the money he made in the NFL. Haynesworth sued in ’13 and was awarded $390,000 in arbitration.

The latest: Earlier this month, after President Donald Trump sparred on Twitter with Iranian leaders, Haynesworth shared a meme on Instagram, joking that the Middle Eastern country ought to bomb the White House. That one was met widely with outrage. “Heck, everybody else was posting it; I thought it was funny as hell,” says Haynesworth, who quickly deleted the post. “Trump started this war, so don’t come over here trying to bomb Nashville. … Maybe I should have just pointed to his golf course,” he quips.

Haynesworth considers all the missteps and all the misfortune, all the mistakes he made and all the wrongs done upon him, and he assesses: “speed bumps.” He says “karma” will take care of his former financial adviser, and he will “do right” by his kids. He moved back to Tennessee, after years in Florida, to work on his relationships with his four children, all of whom he now lives near. He’ll take his 13-year-old daughter, Alanie, for mani-pedis; ride scooters with Aivery; watch Ahsharri crush drives at the local Topgolf; ferry his youngest, 4-year-old Ayden, to the park.

“Losers live in the past,” he says. And Albert Haynesworth is not a loser. He will get the kidney, turn his life around, make millions, move into a larger house, reclaim more or less what once was his.

How he’ll do this remains to be seen. His is not a name off which he can easily trade.

Instead he shops for groceries in the afternoons and cooks salmon or pasta feasts for his girlfriend, Kimberly Willie, at night. He takes his children to lakes, on the lookout for turtles and snakes. He recently attended his 20-year high school reunion, but he says he didn’t at all consider what his classmates thought of him. If anything, he hopes they looked his way and realized they’re not all that different.

Haynesworth does not want to project sadness. He says it over and over: He’s fine. But melancholy tends to hang over him like a cloud, with all the hospital visits and the health scares. Here’s a man who had everything and then lost virtually all of it. He has three stents in his heart, one in his brain, and there’s pain hidden behind his dark-brown eyes. He alludes vaguely to plans that he hopes will change his legacy, suggesting that deep down he cares about how he is perceived. He wants to build a community center back in Hartsville. Or an orphanage. Or revitalize an entire neighborhood. He might develop commercial properties in Puerto Rico. “Leave my mark on the world,” he says. But he doesn’t seem to have concrete plans or the cash flow to accomplish any of this.

First he has to get healthy. As Haynesworth continues to lose dialysis friends, he says he sometimes thinks about death. But he doesn’t fear it. He says he doesn’t fear anything. “I’m gonna go when God’s ready for me to go.”

“I worry about [Albert] a lot,” says Washburn.

Don’t, Haynesworth says.

* * *

When Haynesworth’s kidney problems landed him in the hospital last summer, he posted about the ordeal on social media, along with the phone number for the Vanderbilt Medical Center. To his surprise, hundreds of people commented. Thousands, he says, called. “I guess,” he says, “I wasn’t as hated as I thought.”

Among those concerned parties: Andre Gurode. He and Haynesworth each made the Pro Bowl following the 2007 season, a year after the stomping incident, and there they talked about their run-in. On the flight home from Hawaii, Gurode found himself seated next to Haynesworth’s older brother, Ty, who further explained that Albert knew he was wrong—and right there Gurode decided to let go.

That sentiment was cemented over the subsequent years as Gurode watched Haynesworth struggle, in football and in life. He couldn’t resent his attacker, couldn’t carry any hatred or project anger into the world. “I want [Albert] to be O.K.,” he says. “I’ve forgiven him.”

Thirteen years later, people still ask both men about that play, even more so after Browns defensive end Myles Garrett similarly snapped this season, in Week 11, ripping the helmet off the Steelers’ Mason Rudolph and swinging it at the quarterback’s head. Gurode is proud he kept his emotions in check, but he says he understands what can lead a player to lash out—he experienced first-hand the emotions and the violence of the game, how fine the lines can be. “Most people tend to think that football players are gladiators with no feelings,” he says. “We’ve all got scars. I’m going to have to explain that moment to my grandkids. I want them to know strength came from my not reacting.”

Sentiments like that haven’t exactly changed Haynesworth himself, but they’ve led him to reconsider the world around him, how people consume his story. Maybe people can forgive. Maybe villains can earn absolution.

Haynesworth, meanwhile, doesn’t know for certain if or when he might get a new kidney. He says his doctors projected it could take three to six months, and that was six months ago. The National Foundation for Transplants paints that window closer to two years (and notes that a transplant can cost upward of $400,000 before insurance). Finding a living donor could speed up the process, and here Haynesworth has a friend, Shawn Vinson, from his Florida fishing days, who recently passed a third (and hopefully final) round of donor-match tests. Vinson is 43 and healthy, in good physical condition. He expects to be able to throw his friend a lifeline sometime in 2020.

“I just hope people donate” in general, Haynesworth says, pointing out that more than 100,000 names remain on the national organ-transplant waiting list. If every person who offered him support were willing to donate a kidney to someone else, he says, “we could make a real dent.”

Until that day he’ll wait, warmed by the sympathies he insists he never sought, reconsidering his relationship with the world around him. Those people who hated the worst thing Haynesworth ever did, they were right to be angry. He knows this. But he can draw strength from those strangers too. He can learn a thing or two about humanity and pain and how people in the most unkind of worlds can still be galvanized to help those in dire need—even if that person in need is Albert Haynesworth, the football scoundrel who didn’t change, but whose circumstances did.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.